-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Food and Public Health

p-ISSN: 2162-9412 e-ISSN: 2162-8440

2015; 5(4): 114-121

doi:10.5923/j.fph.20150504.03

Serum Adiponectin Level and Nutritional Status among Coronary Artery Disease Patients

Hanan H. Eskandar1, Nesrin K. Abd El-Fatah2, Olfat A. Darwish3, Eman M. El Sharkawy4

1Consultant of clinical pathology, Alexandria University Students Hospital, Egypt

2Lecturer, Nutrition department High Institute of Public Health, Alexandria University, Egypt

3Professor, Nutrition department High Institute of Public Health, Alexandria University, Egypt

4Assistant Professor, Cardiology department faculty of medicine, Alexandria University, Egypt

Correspondence to: Nesrin K. Abd El-Fatah, Lecturer, Nutrition department High Institute of Public Health, Alexandria University, Egypt.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2015 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

Background: Central adipose tissue is now considered to be a large endocrine gland secreting a large list of adipokines. Most of these adipokines are atherogenic with the exception of adiponectin. Objectives: To assessment of serum adiponectin level in relation to nutritional status of coronary artery disease (CAD) patients. Material & Methods: A cross-sectional study was carried out on coronary artery patients attending Alexandria University Student Hospital, Egypt. CAD cases of both sexes were interviewed for dietary intake assessment using a food frequency questionnaire and twenty four hour recall methods, body weight, height and waist circumference were measured. Serum adiponectin level was measured using the ALISA technique and lipid profile was estimated. Results: Morbid obesity was very common among female patients and much more prevalent than among male patients, but obesity was not correlated with the level of adiponectin in serum. Serum adiponectin levels were significantly higher in females than in males, and was also significantly higher in smokers. In males adiponectin levels showed a positive correlation with high density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) levels and a negative one with serum triglycerides (TG) levels. While in females the daily intake of plant fats and the percentage of energy provided from them showed an inverse association with adiponectin levels. Conclusions: Findings are strongly suggestive that adiponectin decreases in males, smokers and patients with high serum TG and high plant fat intake, while increases in females, ex smokers and patients with high HDL-C levels. While not correlated with any of the anthropometric measurements.

Keywords: Central obesity, Adipocytokines, Adiponectin, CAD

Cite this paper: Hanan H. Eskandar, Nesrin K. Abd El-Fatah, Olfat A. Darwish, Eman M. El Sharkawy, Serum Adiponectin Level and Nutritional Status among Coronary Artery Disease Patients, Food and Public Health, Vol. 5 No. 4, 2015, pp. 114-121. doi: 10.5923/j.fph.20150504.03.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Adipose tissue is considered to be a large endocrine gland. The communication between adipose tissue and other biological systems is established through the expression of a large number of bioactive mediators that are collectively called adipokines. [1] adipokines include leptin, tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), interleukin-6 (IL-6), adipsin, acylation stimulating protein, adiponectin, macrophage and monocyte chemoattractant protein, lipoprotein lipase, angiotensin-2, plasminogen activator inhibitor-1, prostaglandins, Visfatin and Resistin. [2] Most of these adipokines are atherogenic with the exception of adiponectin [3].Adiponectin improves insulin-mediated glucose uptake by skeletal muscles and suppresses hepatic glucose production. [4] It promotes fat oxidation, reduces TG content in skeletal muscles and ameliorates insulin resistance. [5] It has a vaso-protective effect through increasing the production of nitric oxide by endothelial cells, improving endothelium reduction oxidation state by suppressing NADPH oxidase-derived superoxide generation, [6] suppressing endothelial cell apoptosis, [7] and promoting vascular healing and angiogenesis. [8]Adiponectin levels have been associated with age, gender [9] and smoking. Diet and exercise increase its circulating levels. [10] The larger adipocytes found in obese subjects produce lower levels of adiponectin but higher levels of proinflammatory cytokines, such as TNFα. [11] Weight reduction significantly increases circulating adiponectin levels. [12] Hypoadiponectinemia is an independent risk factor for developing metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes mellitus. [13] Furthermore, it is a risk factor for patients with obesity-related diseases such as atherosclerosis, CAD and hypertension. [14] Currently, several epidemiological studies have shown that low adiponectin is associated with increased risk of CAD. [15] Control of atherosclerosis-promoting diet, through lifestyle changes, reduces multiple metabolic CAD risk factors, including low adiponectin levels. This study was done to investigate serum adiponectin level and its relation to nutritional status in coronary artery disease patients.

2. Materials & Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting

- A cross-sectional study conducted in Alexandria University Students Hospital, Egypt.

2.2. Study Population, Sample Size and Sampling Strategy

- Using G Power program and based on the detected mean adiponectin level among CAD patients of 10.4 and an SD of 4.4 and assuming a 15% change from normal around the detected mean and using a 5% level of confidence and an allowed alpha error of 5% and a power of 80%, the minimum required sample size amounted to 82 CAD patients. All eligible patients within a period of four months were included in the study until the required sample size was fulfilled. Diagnosis was done based on clinical picture, electrocardiogram changes, enzymatic changes, and coronary angiography with exclusion of pregnant women or patients with chronic renal failure, acute or chronic hepatitis, congenital or valvular heart disease, acute MI, or patients on weight reducing programs. All eligible patients within a period of six months were included in the study until the required sample size was fulfilled.

2.3. Data Collection

- Participants were interviewed through a pre-designed questionnaire which including personal characteristics, medical, drug and family histories and lifestyle habits (smoking, plus tea and coffee consumption).

2.4. Anthropometric and Blood Pressure Measurements

- Body weight, height, and waist circumference were measured [16]. Blood pressure was measured using a mercury column sphygmomanometer. WHO cutoff value of≥140/90 was used. [17]

2.5. Dietary Intake Assessment

- Food consumption pattern was assessed using food frequency questionnaire [18]. Detailed list of food and beverages intake during the previous twenty four hours was recorded and amount was determined by use of household measures. Energy, macronutrient and types of fat intake were obtained using the Egyptian food composition tables [19]. The percent of energy derived from macronutrients and different fatty acids was calculated.

2.6. Laboratory Assessment

- Fasting blood samples were collected to estimate blood glucose level, and lipid profile. The determination of fasting blood glucose and lipid profile was carried out on a cobs c 311 analyzer (Roche Diagnostics). Adiponectin was measured by ELISA technique [20] using AviBion Human Adiponectin (Acrp30) ELISA Kit from Orgenium Laboratories. Total plasma adiponectin levels typically range from 3–30 μg/ml, in normal human subjects. [21]

2.7. Statistical Analysis

- Data analysis was performed using the SPSS software version 16. (SPSS, Chicago, Illinois, USA) For descriptive statistics mean and standard deviation was used. For analysis of numeric data Kolmogorov-Smirnov, Mann-Whitney tests were used. To test the association between 2 categorical variables, Pearson’s chi square test, Mont Carlo exact test and fisher exact test were used. Finally, correlation was used to test the nature and strength of relation between two quantitative/ordinal variables. The P-value less than 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant. The Spearman correlation coefficient (r) is expressed as Pearson coefficient. The sign of (r) indicates the nature of correlation (positive/ negative), while the value indicates the strength of relation.

2.8. Ethical Considerations

- The study was approved by Ethics Committee of High Institute of Public Health. Every patient was informed about the purpose of the study and written consent to participate in the study was obtained and confidentiality was assured.

3. Results

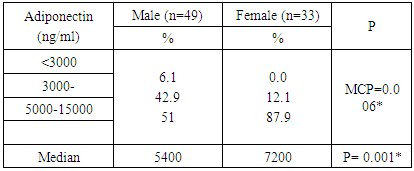

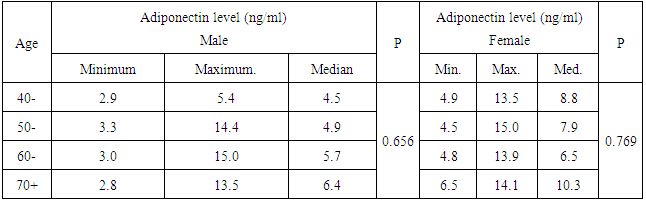

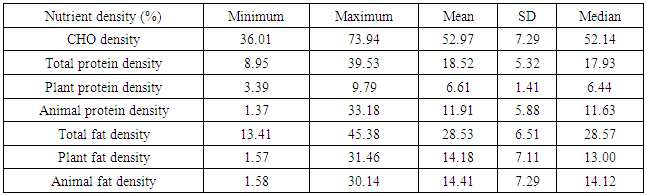

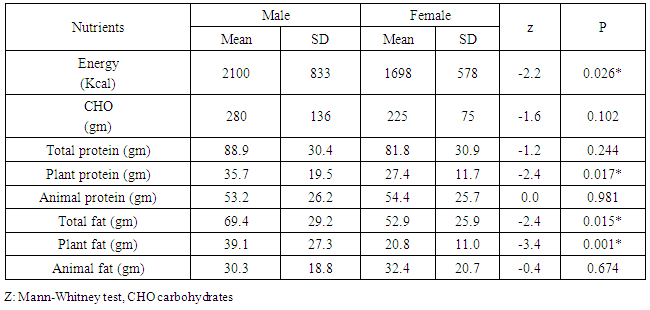

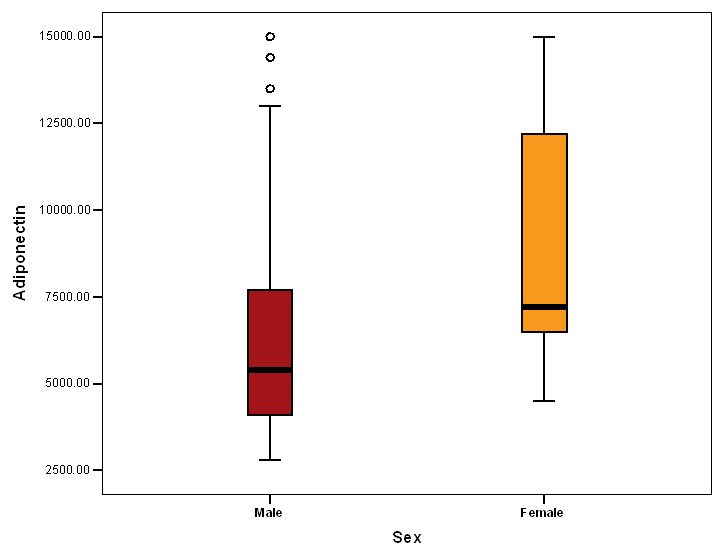

- The study included CAD Patients 49 males aged 60-70 years and 33 females aged 50-60 years. Adiponectin was significantly higher in females than in males. The serum values ranged between <3000-15000 ng/ml with median value of 7200 and 5400 in females and males, respectively. Eighty eight percent of the females and 51 % of the males in the a serum adiponectin category values of 5000 to less than 10000 ng/ml. the higher values of adiponectin in females was consistent in all age groups. (Tables 1, 2 & Figure 1).

| Figure 1. Adiponectin level in both sexes |

|

|

|

|

|

|

4. Discussion

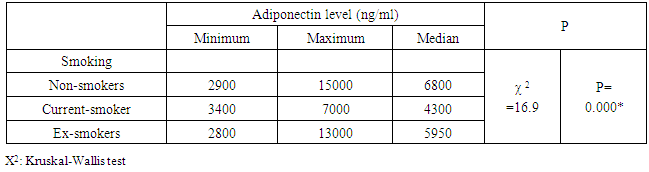

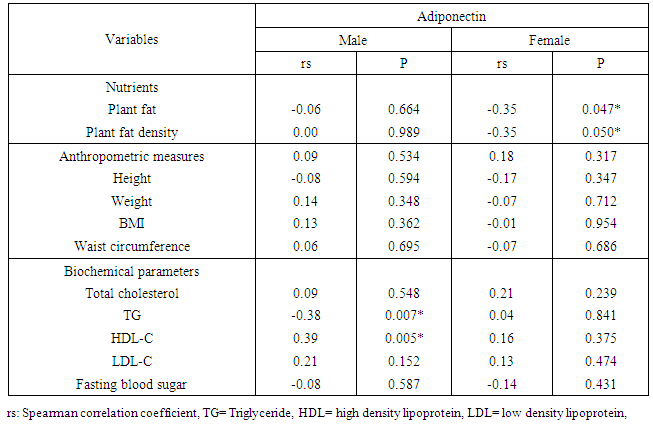

- Many studies suggest that visceral adiposity has adverse metabolic effects stronger than subcutaneous fats. [22] Studies on adiponectin concentration in relation to different types of adiposity showed controversial findings. Many studies reported a negative association between adiponectin levels and both body mass index BMI, [23-25] and waist circumference [26]. One study found no relation with waist circumference [27] and others did not report any correlation between adiponectin levels and BMI [28]. This was consistent with our results where no significant correlation was found between adiponectin levels and weight, BMI or waist circumference. Still others reported that there was no correlation with BMI and a negative correlation with waist circumference. [29]The daily intake of different nutrients showed that there was a significant negative association between adiponectin level and intake of plant fat among female patients. There have been few studies on the association between dietary intakes and adiponectin concentrations. One study showed no correlation between adiponectin and total energy, protein, fat or carbohydrate intake. [30] another one showed that diets low in glycemic load and high in fiber were associated with higher adiponectin concentrations. [31] Mantzoros et al. concluded that close adherence to a Mediterranean-type diet is associated with higher adiponectin concentrations [32]. Our study, patients were actually received a nutritional advice, their nutrient density was ideal (carbohydrates 53%, protein 18.5% and fats<30%). More than ninety percent of our patients were consuming fish and non fatty poultry weekly and 89% of them were consuming whole grain bread daily. Newly diagnosed CAD cases are recommended to discover the dietary intake relation to adiponectin level. In this study, the lipogram of male patients showed a strong negative correlation between serum adiponectin and TG level and a strong positive correlation with HDL-C level. No significant association was found with total cholesterol level or LDL-C level, and no significant association was found between serum adiponectin and parameters of the lipid profile among female patients. This was in agreement with the report by Marso et al. [33]. In a study on CAD patients with newly diagnosed impaired glucose tolerance, a positive correlation of adiponectin to total cholesterol, HDL-C and LDL-C and a negative correlation to TG were found [34]. [28] found no correlation between LDL-C or HDL-C and adiponectin levels.Low concentrations of adiponectin may lead to insulin resistance, which in turn may lower the concentration of HDL-C either by insulin stimulation to the transcription of the apolipoprotein of HDL-C [35], decrease the production of VLDL-C or by enhancing the expression of lipoprotein lipase [36]. Insulin resistance, thus may raise the concentration of TG-rich lipoproteins in the circulation, which may alter the formation and remodelling of HDL-C particles. These correlations fueled the hypothesis that some of the effects of adiponectin on CAD may be mediated via lipid metabolism [37]. As a closer association of adiponectin with HDL-C than with inflammatory markers was found, the lipoprotein effects of adiponectin may be more important than the anti-inflammatory links with TNF-α, IL-6, or C-reactive protein.Serum adiponectin did not correlate with blood pressure or with fasting blood glucose, except for a positive correlation with systolic blood pressure among our study in male patients. Similarly, in previous studies, no correlation was found [38] However, another study concluded that adiponectin was inversely associated with other traditional cardiovascular risk factors, such as blood pressure and heart rate. [39]. Adiponectin was significantly higher in females than in males. This finding is consistent with previous studies. (25, 39) These differences may be related to the differences of fat distribution and metabolism, [40] and the selective inhibition of the secretion of adiponectin by testosterone. [41], [28] showed no difference in adiponectin levels between men and women. [28] [23, 25] reported that smoking was associated with lower adiponectin levels and this was in agreement with our results. Fewer studies found no association. [28, 34] Increasing activity of the sympathetic nervous system, which is affected by nicotine decreases plasma levels of adiponectin. Moreover, β-adrenergic agonists and cyclic AMP analogues inhibit the gene expression of adiponectin. [42]Concerning most of the individual drugs, there was no significant difference between adiponectin levels among the patients who use the drug and those who do not use it. Two exceptions were noticed, calcium channel blockers and statins users, where serum adiponectin was significantly higher among those who use them. Other studies showed conflicting results regarding the effects of statins on adiponectin [43, 44]. Some beta-blockers and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor and angiotensin II receptor blocker administration increase plasma adiponectin levels [45], while other beta-blockers reduce it. [46]In our study population, among the 46 diabetic patients, 13 patients were receiving insulin. Regarding insulin effect on adiponectin expression, existing data are controversial. studies suggest that either insulin decreases [47] increases adiponectin expression [48] or had no impact [49]. Twenty four of our patients (32%) were receiving oral hypoglycemic drugs. Glimepiride was shown not only to improve insulin resistance, but also to increase plasma adiponectin levels in elderly patients with type 2 diabetes [50]. By contrast, metformin does not alter plasma adiponectin levels [51].

5. Conclusions

- In conclusions. Currently, it is not clear whether adiponectin is a real protective factor in the CAD or more a bystander reflecting other risk factors. In our population, we found a negative correlation to other risk factors such as smoking habits or TG and a positive correlation to the protective HDL-C. Against expectations, we found no correlation to LDL-C, weight, waist circumference or BMI.Some limitations in the present study, however, should be mentioned. A Small sample size, and small number of newly diagnosed CAD cases. Due to the cross sectional design, it is unclear whether the biomarkers reflect metabolic abnormalities that led to CAD or whether they are a consequence of it so a prospective study would be desirable but difficult. Finally, The assay used in our study measured total serum adiponectin levels, and we were therefore unable to estimate the levels of the various isoforms of adiponectin, which may reflect differing biological effects (for example, the HMW form is potentially associated with slightly greater insulin sensitivity) [37].Recruiting patients with CAD in both genders with wide range of age was the main strength of the present study. In addition, testing the associations between adiponectin and other parameters separately in males and in females is added. Finally, the use of population-based samples, standardized collection of nutritional data, use of an improved nutrient database, and use of multiple quality-control procedures are strengths.It is recommended that a structured health education programs that emphasizes lifestyle changes should include Abstinence from smoking and nutrition education for healthy choices. In addition, further studies should be conducted concerning adiponectin and CAD using the prospective design and newly diagnosed patients.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML