-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Food and Public Health

p-ISSN: 2162-9412 e-ISSN: 2162-8440

2015; 5(3): 77-83

doi:10.5923/j.fph.20150503.03

Consumer’s Knowledge, Attitude, Usage and Storage Pattern of Ogi – A Fermented Cereal Gruel in South West, Nigeria

Adebukunola M. Omemu A. M.1, Mobolaji O. Bankole2

1Department of Foodservice and Tourism, Federal University of Agriculture, Abeokuta (FUNAA), Ogun State, Nigeria

2Department of Microbiology, FUNAAB, Ogun State, Nigeria

Correspondence to: Adebukunola M. Omemu A. M., Department of Foodservice and Tourism, Federal University of Agriculture, Abeokuta (FUNAA), Ogun State, Nigeria.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2015 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

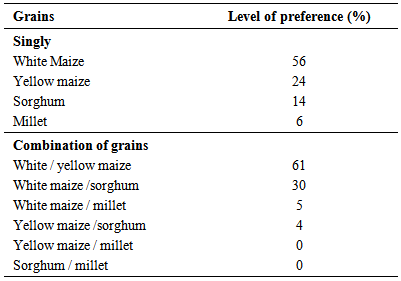

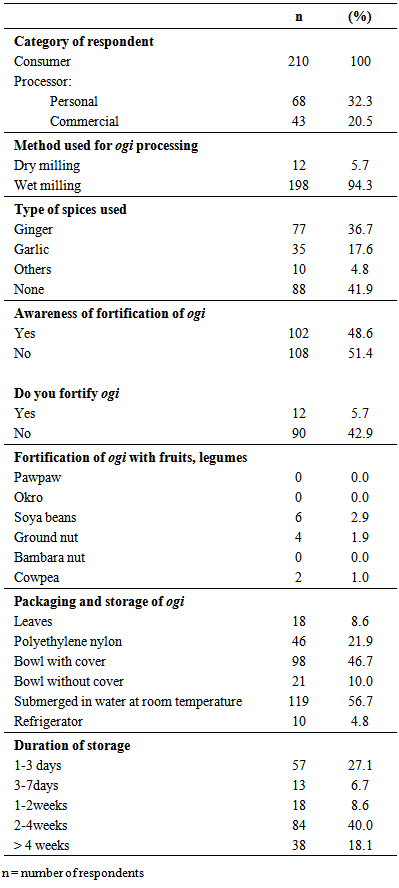

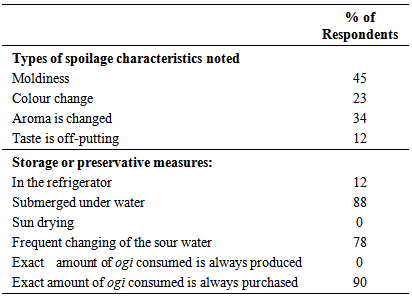

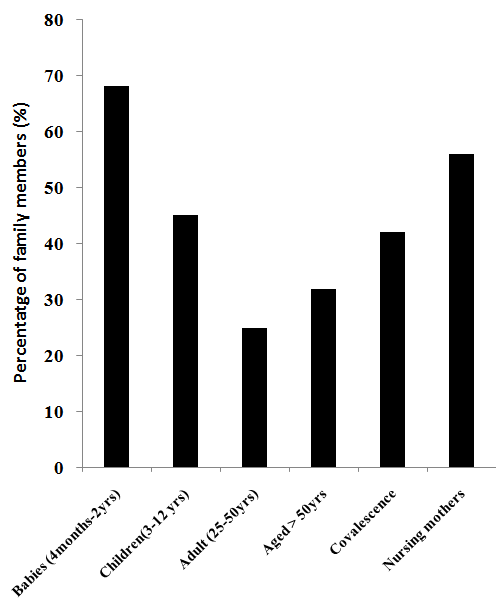

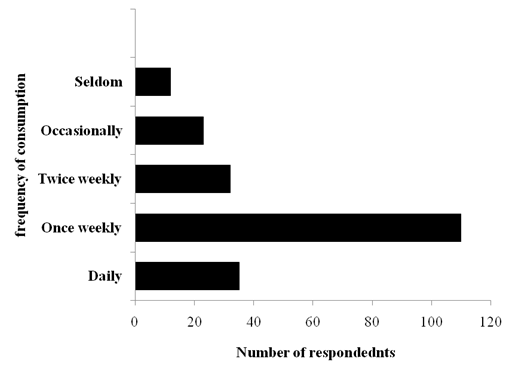

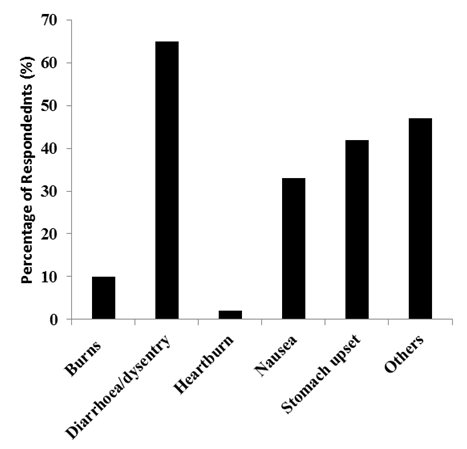

The perceptions, knowledge and attitude of the consumers of ogi – a common fermented cereal gruel was studied. A semi structured, validated questionnaire and a face-to-face interview was used to obtain information on the type of grains used for processing, the processing techniques and frequency of consumption. White Maize, yellow maize, sorghum and millet were used in ogi production in decreasing order of preference. The grains were used singly or in combination. Some (32.3%) of the respondents processed ogi for personal consumption while 20.5% processed the ogi for commercial purpose. Majority (207) of the respondents processed ogi using wet milling method. The spices commonly used in the production of ogi are ginger, garlic, black pepper and cloves. Many (102, 48.6%) respondents are aware that ogi can be fortified with some fruits and legumes however only 11.8% of the respondents processed or consumed fortified ogi. Category of family members that consumed ogi are infants between 4 months to 2 years (68%), children between 3 and 12 years (45%), adults (25%), convalescence (42%) and lactating or nursing mothers (56%). Majority of the respondents (52.4%) consumed ogi at least once in a week; 16.7% consumed it daily, and 15.2% consumed it twice in a week. Submergence in water and frequent changing of sour water was identified as the most effective way of storing and preserving ogi. Respondents reported the use of the supernatant of ogi and uncooked ogi in the management of diarrhea or dysentery (65%), common stomach upset (42%) and nausea (33%). The need for nutrition education of consumers of ogi to encourage consumer to accept the views of the experts is recommended.

Keywords: Steeping, Souring, Storage, Ogi, Maize, Sorghum and millet

Cite this paper: Adebukunola M. Omemu A. M., Mobolaji O. Bankole, Consumer’s Knowledge, Attitude, Usage and Storage Pattern of Ogi – A Fermented Cereal Gruel in South West, Nigeria, Food and Public Health, Vol. 5 No. 3, 2015, pp. 77-83. doi: 10.5923/j.fph.20150503.03.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

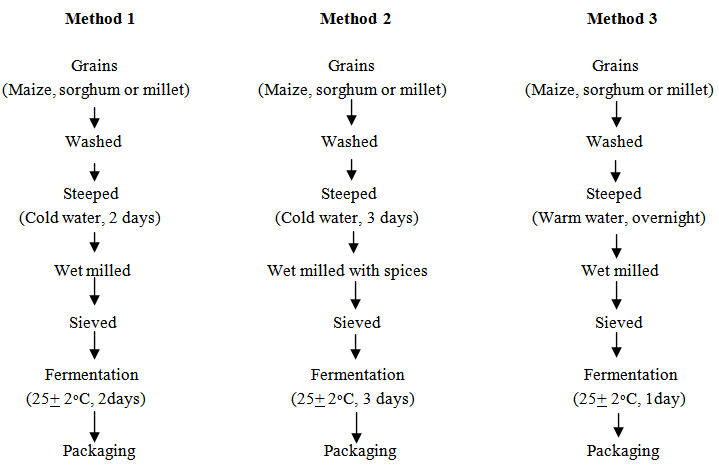

- The Nigerian indigenous fermented foods constitute a group of foods that are produced in homes, villages and small scale cottage industries. They are sold to the rural populace who buy them for food and social ceremonies. The fermented foods are derived from substrates like roots, legumes, cereals, oilseeds, nuts, meat, fish, milk and palm tree sap (Oguntunde, 1989; Uzogara et al., 1990). One of the popular indigenous fermented foods in Nigeria is ogi which is a fermented cereal porridge made from maize (Zea mays), sorghum (Sorghum vulgare) or millet (Pennisetum typoideum). The ogi porridge is very smooth in texture and has a sour taste reminiscent of that of yoghurt (Banigo and Muller, 1972). In Nigeria, the uncooked ogi is either prepared into a smooth porridge called “pap” or a solid gel known as “eko” or “agidi. The consistency of the pap varies from thick to watery according to choice. The pap can be sweetened with sugar and milk; it is then eaten with bean cake. The pap is used as the first native food for weaning babies (Onyekwere, et al., 1989; Osungbaro, 1990). It also serves as breakfast meal for pre-school, school children and adults (Odunfa and Adeyele, 1987). In a more concentrated form it is boiled into a thick gel and then allowed to set stiff in leaf moulds as “eko” or “agidi”. In either form, it is usually preferred to many other indigenous foods by the aged and the convalescence. The stages of traditional ogi production include: washing of grains, steeping for 3 days at ambient temperature (28 ± 2℃), wet-milling, wet-sieving with a hand sieve or muslin cloth with about 300 µm pore size and sedimentation/ souring of the filtrate for 1–3days. Thereafter, the water is decanted and the wet, clean sediment (ogi) is collected and stored for personal use or sold to consumers in its wet form in small units packaged in leaves or polypropylene bags (Akingbala, et al., 1989; Adeyemi and Beckley, 1986; Omemu and Omeike, 2010). The physical and biochemical qualities of ogi are influenced by the type of cereal grain, fermentation or souring periods and the milling method (Osungbaro, 1990; Hounhouigan et al., 1993).Many workers have reported on different aspects of ogi production. Particular attention has been given to process variations, process mechanization, and nutritional improvement (Akinrele 1970; Banigo et al. 1974; Onyekwere et al., 1989; Olasupo et al. (1997). The traditional method of ogi processing is accompanied by severe nutrient losses, the magnitude of which depends on the type of grains and the processing method used (Aremu, 1993). Hence, there have been several attempts at improving the nutritional quality of ogi. The strategies used include the addition of high-protein material such as legumes or incorporation of fruits and vegetables such as pawpaw and okra (Akinrele et al., 1970, Adeyemi and Soluade, 1993).Recent works on ogi include the use of starter culture, significance of yeasts in ogi, evaluation of ogi during spoilage, identification of hazard analysis and critical control points during ogi processing (Teniola and Odunfa, 2001, Omemu et al., 2007a,b; Omemu and Omeike, 2010). Ogi, being important cereal porridge in the West African sub-region, has for some time been a subject of scientific evaluations; however, there is paucity of information on the knowledge and attitude of consumers to some of the scientific evaluations. This study was, therefore, designed to assess the knowledge, attitude and usage patterns of ogi by consumers South Western Nigeria. Such information would act as a useful basis for effective application of the interventions designed to improve the product. It is expected that the findings from the study can also serve to guide education programs for consumers of ogi in South west Nigerian.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

- This study was carried out in 2 states (Lagos and Ogun state) in South Western Nigeria. Consumers of ogi were selected within each state using a convenient intentional and reasoned sampling with predetermined quotas as reported by Guerrero et al., 2010. Convenience sampling is often used in exploratory research where the researcher is interested in getting an inexpensive approximation to a specific topic through involving participants who meet specific recruitment criteria with relevance for the subject under investigation. This non-probability method is recommended during preliminary research activities to get a gross estimate of the results, without incurring the cost or time required to select a random sample (Guerrero, 2010). On average 105 consumers of ogi in each state (total n = 210 consumers) were recruited. The first criterion for selecting the participants was their involvement in deciding about purchase of food and preparation of food at home. Only consumers who stated to be involved in these two activities were selected. Second, the different quotas for selecting consumers were age (a minimum of 10% of consumers in each decade from 20 to 70 years old) and gender (a minimum of 10% of individuals of each gender within each age group).

2.2. Data Collection Procedure

- A semi structured, validated questionnaire and a face to face interview was used to collect data on traditional production, consumption, usage and storage of ogi. The questionnaires and interview were administered through research assistants who distributed in person to the participants. The participants were located in their own homes, shops or offices. Each participant was instructed on the correct method of completing the questionnaire. Respondents with difficulty in understanding English were assisted by an interpreter.

2.3. Data Analysis

- Responses to the questionnaire were compiled into frequency distributions. Percentages of subjects responding to each item were calculated using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS).

3. Results

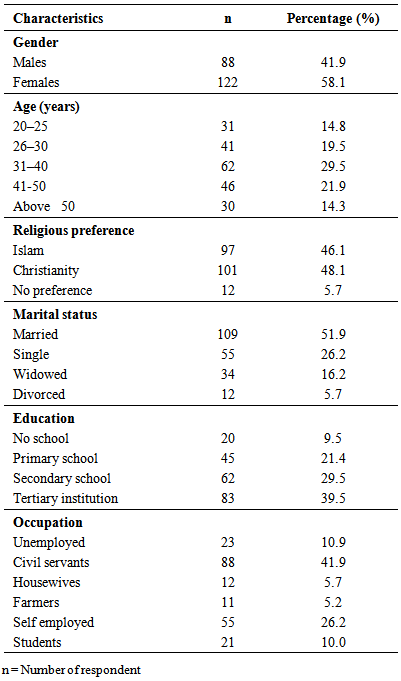

- Table 1 presents the socioeconomic characteristics of the 210 respondents surveyed. Majority (58.1%) of the respondents are female while 41.9% are male. Only 30 (14.3%) of the respondents are above 50 years, 62 (29.5%) are within 31-40 years of age and 31 (14.8%) are above between 20-25 years. Many (109) of the respondents are married, 34 are widowed, 12 are divorced and 55 had never married. Only 97 respondents practice Islamic religion while 101 are Christians. Twenty (9.5%) of the respondents had no formal education while 190 (90.5%) had one form of education from primary school to tertiary institution. Majority (41.9%) of the respondent are civil servants, 11(5.2%) are farmers, 55 (26.2%) are self-employed, 23 (11.0%) are unemployed while 21(10.0%) are students in different institutions.

|

|

|

| Figure 1. Different processing method of ogi by wet milling |

| Figure 2. Category of family members that consume ogi |

| Figure 3. Frequency of consumption of ogi by respondents |

|

| Figure 4. Use of ogi in the management of discomfort, ailment, illness and symptoms |

4. Discussion

- These results showed that the consumption of ogi cut across a wide range of people. Ogi has a widespread application in Sub-Saharan Africa as a weaning food, breakfast meals for school age children and adults, convenient meals for the aged and the convalescent. It is estimated that about 50 million people consume ogi at least once in a week (Dada and Muller, 1983; Steinkraus, 1996).All the respondents who processed ogi either for personal consumption or for commercial purposes are all female. This agrees with previous reports by Omemu and Adeosun, 2010 where the 30 processors of traditional fermented wet ogi surveyed in Abeokuta were all female. Similarly, Watts (1984) reported that the preparation and sale of eko-a popular cold food made of boiled ogi is entirely in the hands of women. These findings suggest therefore, that any public education programs developed on the processing and storage of ogi will need to target females.The order of preference for a particular grain in ogi processing differed between individuals in the same place. However, this study showed a high preference for maize and sorghum in ogi processing. Onyekwere, et al., (1989) reported that production of ogi has been based on maize and sorghum, probably because of the lower market costs of sorghum and maize compared with that of millet as well as the tiny size of millet which hampers cleaning and handling. The mixing ratio for the different combinations also varied and depended on preference. The reasons for proportional mixing of the grains included taste enhancement, color development and increase in certain nutrient components. Some respondents did not offer any reason for using the grains in combination but it appeared that most of the producers and consumers are aware of certain nutrient deficiencies among cereals.Several reports had shown that dry-milling of fermented maize for ogi production improve the nutrient content of ogi by conserving the nutrient as well as enhancing the shelf life while wet milling results mostly in nutrient-loss, yield mainly starch and allows contamination from dirty water (Ruud and Rosa, 2002; Dal et al., 2007). However, most consumers of ogi in this study still prefer and use the wet milling processing; this has serious nutritional implications for consumers of ogi especially the infants, aged and the convalescence. The technology of production of ogi by wet milling varied based on producer’s taste especially for individuals producing for home consumption. The production is predominantly at the household level using only a few pieces of equipment and home utensils. The materials used for steeping the maize included various sizes of plastic buckets, plastic drums and metal drums. The water used for steeping also varied depending on the water source of the respondents. The usual steeping medium observed in this study was well water, bore-hole water and tap water. The use of hot or warm water for steeping was observed mostly with commercial processors and the purpose was to reduce the steeping time. Spices, when used in ogi production constituted only 1% or less by weight of all of the ingredients used. Spices impart pungent flavor hence only small quantities are used (Adeyemi and Umar, 1994). Most of the respondents that used spices for ogi production used it to enhance the sensory attributes of the ogi. Adesokan et al., (2010) reported that incorporation of 5% ginger into ogi led to a relatively improved sensory attributes, a reduction in microbial load during storage and hence an improved shelf life.Packaging of wet ogi in small unit transparent polyethylene nylon or leaves was only necessary when it is produced for commercial purposes. For personal use, ogi was stored submerged under water in buckets, basins or drums. The water is frequently changed to prevent spoilage. Despite abundant global food supplies, widespread malnutrition persists in many developing countries. In Nigeria, and indeed most developing countries, the underlying problems have been identified to include poverty, inadequate nutrient intake and ignorance about nutrient values of foodstuff. Major international and national efforts towards addressing these problems include nutritional supplementation and fortification of staple foods. As cereals are generally low in protein, supplementation of cereals with locally available legume that is high in protein increases protein content of cereal-legume blends (Bressani, 1993). From this study, it is evident that most of the respondents are aware of the fortification of ogi with fruits and legumes; however this knowledge was not translated to practice by the surveyed respondents. Many of the respondents claimed that fortification with legumes result in ogi with a beany flavor which is unacceptable by many the consumers. The processing of ogi is arduous and time consuming; ogi is usually produced in large quantity and store for use. The use of ogi in the management of some infection and illnesses agrees with several reports. The sour water of wet ogi has been traditionally found to be of medicinal importance in the South-Western part of Nigeria. It is used to soak bark of root of some plants to treat not only fever and malaria but is popularly used as solvent for herbal extraction. It has been used in the extraction of antimicrobial agents from some leaves such as Bryophyllum pinnatum and Kalanchoe crenata (Aibinu et al., 2007). According to Aderiye and Laleye, (2004) some local communities in southwestern Nigeria usually administered uncooked ogi to people having running stomach to reduce the frequency of stooling. Some reports have shown that ogi has the potentials for use in diarrhea control and other related gastrointestinal tract illnesses or discomforts (Odugbemi, et al., 1991; Olasupo, et al., 1997).

5. Conclusions

- The consumption of ogi cuts across different people in the society. This study showed that there is the need for nutrition education of consumers of ogi to encourage consumer to accept the views of the experts on the processing and fortification of ogi.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML