-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Food and Public Health

p-ISSN: 2162-9412 e-ISSN: 2162-8440

2014; 4(6): 259-265

doi:10.5923/j.fph.20140406.01

Academicians’ Attitude towards “New Foods”

Leyla Ozgen

Department of Food and Nutrition Education, Gazi University, Ankara, Turkey

Correspondence to: Leyla Ozgen, Department of Food and Nutrition Education, Gazi University, Ankara, Turkey.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2014 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

It is known that some people are more often to trying new foods them others. Today, it is common for university academics to travel internationally for conferences, research, and extended study. This research investigates the taste preferences of academics in Ankara, Turkey. The aim of this paper has been conducted to determine academicians’ attitude towards new foods. This study design was a descriptive cross-sectional of faculty and academic staff from more than 5 public and private Universities in Ankara, Turkey. Data (n=722) were collected from more than five public and private Universities in Ankara, Turkey. Academics were given a survey asking them to rate their attitudes towards trying new foods. The scale was modeled after the 5 point Likert scale. Academicians’ attitudes towards new foods scale were asked to rate these foods on a variety of measures including; attitude about “open to new tastes”, “inquisitive about new tastes” and “skeptical about new tastes”. Personal innovation scales were grouped as “innovators”, “late majority” and “laggards”. When results were examined, a high level of correlation between “laggards” subscale of personal innovation and “open to new tastes” and “inquisitive about new tastes” subscales was found, while it has medium level of correlation with “skeptical about new tastes” subscale. Another result of the study is that there is a statistically significant difference between average scores of “open to new tastes” and “inquisitive about new tastes” subscales with regards to length of residence place. It is found that people having lived abroad for a long time are more “open to new tastes” and “inquisitive about new tastes” than people who have limited or no experience living abroad. As a result, when individuals are exposed to the culture of different countries and various ethnicities, it causes them to adopt new kinds of food more easily.

Keywords: Food neophobia, Eating behavior, Live in abroad, Longest residence places

Cite this paper: Leyla Ozgen, Academicians’ Attitude towards “New Foods”, Food and Public Health, Vol. 4 No. 6, 2014, pp. 259-265. doi: 10.5923/j.fph.20140406.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Individual’s fear of tasting a new food that is not accustomed is called food “neophobia” [1]. For an individual who has a fear of tasting new food, while evaluating a new food, this fear prevents both tasting the new food and feeling the taste of this new unaccustomed food [2]. It is stressed that correlation between familiarity of a place and its image as a destination is important [3-7]. It is also stated that familiarity of local foods is associated with knowing these local foods. Many people’s attitude towards new tastes in unfamiliar cuisines has changed in a positive way due to the effect of globalization [8-10].Food consumption is directly related to food choice. It is examined that factors like individual’s sense of taste, health, social status, budget, personal and social factors, eating habits and food samples, environmental factors and orientation, and factors such as focusing upon values over cognitive and adaptation factors affect food choice [11-14]. It is indicated that willingness to taste a new food especially in tourism in which an individual wishes to visit changes according to individual’s familiarity of the local foods [10]. It is also stated that tourist’s food consumption is affected by the factors like the culture of the region, social-physical- psychological situation and environmental and sensual factors [15, 16]. It is found that motivational factors, compulsory effects and previous experiences, personal attributes about the food, socio-demographic factors, culture and religion have an influence on tourist’s food consumption [17]. In other studies, it is stated that even prohibitions in religion about tasting a new food can be disregarded according to the circumstances a person experiences [18, 19].Adoption of a new food by consumers is not easy, they are anxious while tasting and eating new foods, so consumers’ acceptance and demand of new food is important [20-24]. Several studies show that young people have more willingness to taste new and exotic foods than middle aged and elderly groups [25-27]. Also, when the existence of food in an environment is compared in terms of rural and urban regions, people living in urban areas are both more willing to taste new foods and more likely to encounter new kinds of foods than people in rural areas [28, 29]. However, it is stated that since the people living in rural areas are less likely to encounter exotic foods, food neophobia level is higher in people live in rural areas [30, 28]. In another study it is stressed that as the education and income level of an individual increase, he becomes more willing to taste new kinds of foods [26, 31]. Nevertheless, it is stated that effect of gender on food neophobia is not clear [26]. Some studies claim that males are more food neophobic about tasting new foods [32, 28, 29]. While other studies claim that females are more neophobic [34]. However, no significant difference between males and females has been established [25, 35]. People also have the chance to explore foods in different cultures thanks to their jobs. As the time spent in abroad and education level increase, the anxiety of tasting new foods decreases, while people who have never been in abroad are more anxious about tasting new food [31, 33]. Academicians also visit different cities or countries to attend events like congresses, symposiums and seminars. They encounter foods from various cultures within this process. For this reason, the objective of this study is to determine the academicians’ attitude towards new food.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

- Respondents voluntarily took the survey before going abroad. Three hundred and forty-six of these academicians are female, three hundred and seventy-six of them are male. However, 71.2% of respondents them have lived abroad before (n=514), while 28.8% of them have never been in abroad (n=208). And so, 11.9% of them have bachelor’s degree, 34.2% of them have master’s degree and 53.9% of them are PhD. When the length of residence is examined, it has been determined that 74.3% the respondents of them lived in city center, 13.2% of them lived in small towns and 12.5% of them were from other countries. The original data set was 722. However 208 responses were eliminated because they had not lived abroad as the study wanted to investigate the attitudes at people who had international experiences.This study is conducted to determine academicians’ attitude towards new foods. Its population is composed of the academic staff of public and privately universities in Ankara, Turkey. The sample group consists of 722 volunteer academicians from various faculties in these universities who accepted to participate in the study.

2.2. Materials

- In this study design was descriptive cross-sectional, “Attitude towards New Foods Scale”, “Personal Innovation Scale” and “Personal Information Form” has been used as data collection tools.

2.3. Attitude towards New Foods Scale (ATNFS)

- Individuals’ taste habits are mostly at traditional level and they become more inquisitive. As they experience different kinds of foods, they become more open to new tastes due to familiarity with other cultures and cuisines [36, 37, 30]. This tool has been developed by the researcher by taking these phases into account. Scale consists of three main subscales and 37 items of “open to news tastes” (13 items), “inquisitive about new tastes” (12 items), “skeptical about new tastes” (12 items). Each item in the scale is evaluated by a 5 point Likert scale from 1=definitely disagree to 5=definitely agree. Method of scoring (5, 11, 18, 21) is coded in reverse (1=5, 2=4, 3=3, 4=2, 5=1). Scoring average of 45.52 is defined as “open to new tastes”, 47.00 as “inquisitive about new tastes” and 42.00 as “skeptical about new tastes” in the scale. It is found that Cronbach α=0.872 for the total scale. It is calculated that Cronbach α=0.810 for subscale of “open to new tastes”, Cronbach α=0.450 for subscale of “inquisitive about new tastes” and Cronbach α=0.752 for subscale of “skeptical about new tastes”. For instance “I would like to taste a salad including reptiles”, “I would like to taste a salad including jambon (ham)” and “I would like to taste a meal including hedgehog” is ranked in “open to new tastes” subscale. “I would like to taste a food if it is allowed in religion”, “I would taste a food if it is prepared in a conventional taste” items are ranked in “skeptical about new tastes” subscale. “I would taste a food if it is prepared in a place that I trust” and “I approach new tastes with suspicion” items are ranked in “inquisitive about new tastes” subscale.

2.4. Personal Innovation Scale (PIS)

- Personal innovation scale, developed by [38], consists of 20 items. Firstly, scale calculation formula is the sum of =42+ (1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 9, 11, 12, 14, 16, 18, 19.)-(4, 6, 7, 10, 13, 15, 17. and 20.) items. Then participants are grouped as “innovators” (scored between 68-120 points), “late majority” (scored between 68-64 points) and “laggards” (scored below 64 points). Each item is evaluated by a 5 point Likert scale from 1=definitely disagree to 5=definitely agree.

2.5. Personal Information Form

- This form includes demographic questions including the participants’ sex, age, level of education, longest residence place and whether been abroad or not.

2.6. Procedure

- In order to apply the measurement tools, written permission have been taken from relevant deanships and head of departments. Preinterviews with academicians have been held and appointments have been made with volunteers for the application of measurement tool. Application of measurement tools has been conducted by the researcher. Participants have been only explained the aim of the study to prevent from “items of scale” to bias their opinions.

2.7. Analysis

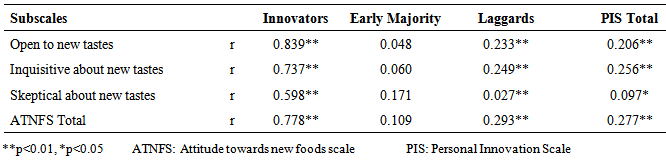

- The data were analyzed by using “Statistical Package for Social Sciences” (SPSS for Windows 20.0). Demographic findings of academicians are stated as frequency. Academicians’ attitude towards new kinds of food scale total and whether its subscales’ staying abroad variable differentiates have been studied by independent-samples t-test. Also, academicians’ attitude towards new foods scale total and its subscales and personal innovation scale total and whether its subscales are differentiate in gender variable have been evaluated by independent-samples t-test. Academicians’ attitude towards new foods and its subscales’ correlation between the longest residence place variable has been examined via One-way ANOVA. In what groups there is a difference has been determined by Post-hoc tukey test. Academicians’ attitude towards new foods and its subscales’ correlation between personal innovation scale total and its subscales have been examined via Bivariate Pearson Correlation. Statistical significance level is determined as (p<0.05).

3. Results

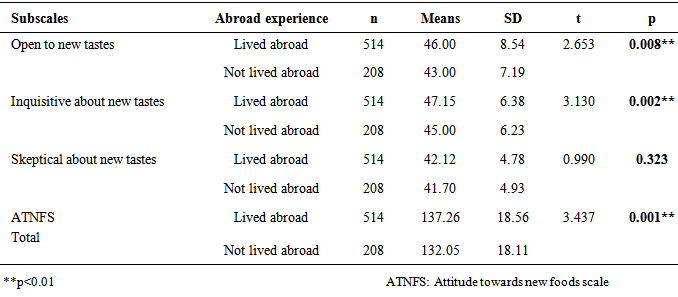

- Firstly, the results of t-test examining correlation between academicians’ attitude towards new foods scale total and its subscales and living in abroad, t-test examining correlation between attitude towards new foods and personal innovation scale total and its subscales and gender. Second, One-way ANOVA examining correlation between attitudes towards new foods and its subscales and longest residence place. Third, One-way ANOVA examining correlation between attitude towards new foods and its subscales and age, and then correlation between attitude towards new foods scale total and its subscales and personal innovation scale total and its subscales are presented below. There is a statistically significant difference between average points of academicians’ attitude towards new foods scale and living abroad variable. While the total of academicians’ attitude towards new foods and living abroad variable point is higher (M=137.26), not lived abroad variable average (M=132.05) is lower but a statistically significant difference is determined despite of this situation (p<0.01), (Table 1).

|

|

|

|

|

4. Discussion

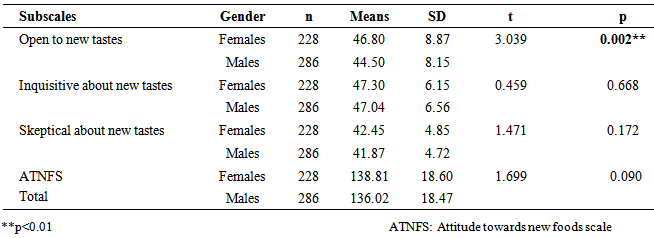

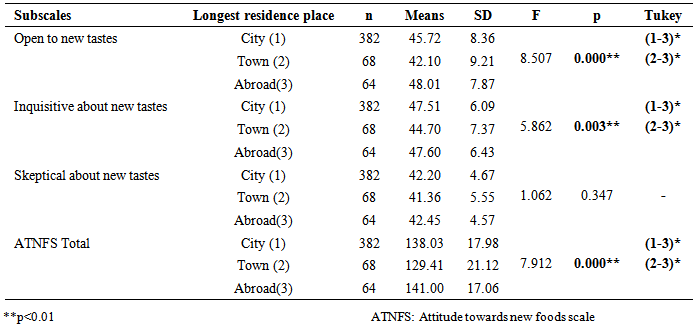

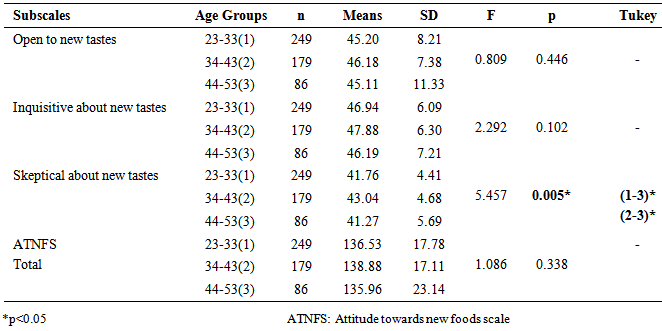

- A statistically significant difference is determined between average scores of “open to new tastes” and “inquisitive about new tastes” subscales with regards to staying in abroad (p<0.01). It is stressed that when people go to trip or visit touristic places they encounter different foods so they start tasting new foods more often [39, 30, 17]. It is also stated that people visiting foreign countries more often are more adventurous, more willingly to taste new foods and more open minded [40]. In another parallel study, it is determined as a result of this study that academicians are more like to be “open to new tastes” and “inquisitive about new tastes” with regards to living in abroad variable. Academicians visit foreign countries average of once or twice for 4-10 days period annually for academic studies like congresses and symposiums. Due to the shortness of this time, academicians may be “inquisitive about new tastes” rather than being “open to new tastes”. Another result of this study on gender subscale is, statistically significant difference is determined in “open to new tastes” subscale between males and female (p<0.01). However there is no statistically significant difference is found between average scores of males and females in “inquisitive about new tastes” and “skeptical about new tastes” subscales (p>0.05). Many studies stated that there is no significant difference between males and females about tasting new foods for the first time [2, 35, 25]. Nevertheless, it is stated that since compared to males, most of the females have the responsibility of preparing meals during the week and weekends [41]; and females enjoy controlling family’s food consumption to [42, 43], females are more open to new tastes. It is also claimed that females are more open to taste new foods since they encounter different and more kinds of food at younger ages. Although similar results can be found for this study, girls are more “open to new tastes” than males since they help their mothers in the kitchen while preparing meals and they are more familiar with various kinds of food than males [33].Another result of the study is that there is a statistically significant difference between average scores of “open to new tastes” and “inquisitive about new tastes” subscales with regards to longest residence place (p<0.01). It is found that people having lived abroad for a long time are more “open to new tastes” and “inquisitive about new tastes” (p<0.01). It states that in individuals’ attitude for new food, when they are exposed to the culture of different countries and various ethnic, it causes them to adopt new kinds of food more easily [34]. As it is stated, people who travel foreign countries frequently, encounter new kinds of tastes more often and they don’t get used to them; however as they are exposed to these food more often, this makes adoption of a new food easier [31]. Although similar results can be seen in this study, due to encountering more diverse food in big cities and travelling to abroad frequently, these individuals become more “open to new tastes” and “inquisitive about new tastes”. Another important result of this study that draws attention is that academicians aged between 34 and 43 have more “skeptical about new tastes” attitudes compared with 23-33 and 44-53 age groups (p<0.05). It is stated that as individuals in 34-43 age group get older they become more “skeptical about new foods” [33]. Also, it is stressed that with the age, the skeptic attitudes to new food increases as well. Moreover, people can be more “skeptical about new foods” because of their social status and role in the family and society [44]. Also people’s previous experiences about new foods (for instance feeling sick or poisoning after eating a new food) can raise suspicion about tasting new kinds of foods [34]. As state that Turkish foods have a unique taste and palate and there are various methods of preparing meals and various types of spices, so they have its own specific tastes [45]. Since there are plenty of hot and cold meals in Turkish cuisine, and they are more delicious, people show “skeptical attitude to new foods”. As well as cultural factors, religious factors also have an important effect on food preferences. Academicians may be “skeptical about new tastes” because of their age groups. Although in this study it is expected that more innovative people in their daily lives are more “open to new tastes” and “inquisitive about new tastes” it is found that they are more skeptic about new tastes. It can be said that academicians’ can be skeptical because they can’t adapt new tastes as they get older. Another important result of this study is that a high level, positive and significant correlation is determined between academicians’ attitude towards new foods scale total and its subscales and personal innovation scale total and its subscales (p<0.01). There is a high level of correlation between “laggards” subscale of personal innovation and “open to new tastes” and “inquisitive about new tastes” subscales while it has medium level of correlation with “skeptical about new tastes” subscale (p<0.01). Moreover it is stressed that academicians’ who have innovative opinions want to taste variety of unknown foods and use them in their daily meals [46, 47].

5. Limitations

- There are certain limitations of this study. It is limited to whether the academicians have been to abroad or not. In further studies the countries that academicians’ visit, the time they stay and its frequency can also be examined. This research is limited to age groups. Further studies can be planned on being “willing to try new tastes” or “open to new tastes” according to young, middle and old age groups. Also comparative analaysis can be conducted among Turkish and foreign academicians who lived to Ankara from other abroad with regards to their attitude towards new food. In order to eliminate the inquisition and late majority about new foods, cooking courses which will provide the opportunity to raise awareness of new food can be given. It may encourage people to try new foods.

6. Conclusions

- In this study it is seen that while academicians are “open to new tastes” they do not abandon “traditional” tastes. In addition, it can be claimed that academicians’ who have innovative opinions are more open to new tastes and “laggards” are skeptic about new foods.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML