-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Food and Public Health

p-ISSN: 2162-9412 e-ISSN: 2162-8440

2014; 4(3): 99-103

doi:10.5923/j.fph.20140403.05

Food Safety Knowledge and Practice of Street Food Vendors in Rural Northern Ghana

Stephen Apanga1, Jerome Addah1, Danso Raymond Sey2

1Department of Community Health and Family Medicine, School of Medicine and Health Sciences, University for Development Studies, P. O. Box 1883, Tamale Ghana

2Tamale Teaching Hospital, Tamale Ghana

Correspondence to: Stephen Apanga, Department of Community Health and Family Medicine, School of Medicine and Health Sciences, University for Development Studies, P. O. Box 1883, Tamale Ghana.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2014 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

Food safety amongst street food vendors is becoming a major public concern especially in urban areas of the developing world where this industry is expanding rapidly. There is rarely any information on street food safety issues in rural northern Ghana where this industry is equally growing rapidly. We therefore conducted this study to assess the knowledge level and evaluate food safety and hygiene practices amongst street food vendors in a rural district of northern Ghana. A cross sectional study was carried out in the Nadowli district where 200 street food vendors were randomly selected from of both densely and none densely populated areas of food vendors. Knowledge level amongst vendors concerning food safety practices was 100%. Although over 96% washed their hands after some major activities, about 13% of them did not use soap. The main storage forms of leftover foods were consumption by friends and family members (13%), reheating (13%) and refrigeration (11.5%). Water storage containers were also found to be used for other activities. 71% of the vendors had undergone medical screening despite a high knowledge level (100%) of its importance. Street food vendors in this rural northern setting generally have a high knowledge level on food safety issues but however do not translate this knowledge into practice.

Keywords: Northern Ghana, Food Safety, Street Food Vendors, Rural

Cite this paper: Stephen Apanga, Jerome Addah, Danso Raymond Sey, Food Safety Knowledge and Practice of Street Food Vendors in Rural Northern Ghana, Food and Public Health, Vol. 4 No. 3, 2014, pp. 99-103. doi: 10.5923/j.fph.20140403.05.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- The World Health Organization defines street foods as ready-to-eat foods and beverages prepared and or sold by vendors on the street and in public places for immediate consumption or consumption at a later time without further processing or preparation. These foods include meat, fish, fruits, vegetables, grains, cereals, frozen produce and beverages [1]. This food industry provides a significant amount of employment, mainly to those with little education and training and often responsible for the feeding of millions of people with a wide variety of foods daily that are relatively cheap and easily accessible [2].In the last few decades, the street food industry has expanded rapidly especially in urban areas of low- and middle-income countries, in terms of providing access to a diversity of inexpensive foods for low- income households in particular [3]. However, this expanding sector is not without its own problems as food safety is now a major public health concern where serious outbreaks of food borne diseases have been documented in the past decade, illustrating both the public health and social significance of these diseases especially amongst children were the impact is most felt [4]. In Africa, the incidence of both food and water borne diseases is estimated at 3.3 to 4.1 episodes per child per year accounting for between 450,000 to 700,000 deaths in children annually, with many more sporadic cases remaining unaccounted for [5]. Some studies in Africa have shown that the tremendous unregulated growth of street food vendors has placed a severe strain on city resources, such as water, sewage systems and sometimes even interfere with city planning through congestion and littering which tend to adversely affect daily life [6, 7].Lots of efforts have been made by health ministries of developing countries in the field of food safety and hygiene education amongst street food vendors. Although these efforts have led to an increase in awareness and knowledge levels of food safety and hygiene practices, this knowledge is however not always translated in to actual practice [8, 9]. Concerns over food borne diseases in Ghana have led to efforts by the relevant authorities to improve on food safety measures and also encourage vendors to adopt more hygienic practices over the past decade [10, 11]. Much of these efforts however appear to be concentrated in the urban areas to the neglect of rural communities as evidenced in a number of studies carried out to evaluate food safety practices in urban areas of Ghana [11- 16].The District Health Management Teams (DHMT) in collaboration with the district assemblies in rural Ghana regulates and educates street food vendors on food safety and hygienic practices. There is currently scarcity of data and knowledge on awareness level and food safety practices on street food vendors in rural Ghana and especially in rural northern Ghana. It is therefore in view of this that we conducted a study to assess the knowledge level and evaluate food safety and hygiene practices amongst street food vendors in the Nadowli district of northern Ghana.

2. Methodology

2.1. Study Area

- The Nadowli District is located in the heart of the Upper West Region of Ghana. It lies between latitude 11º 30’ and 10º 20’ north and longitude 3º 10’ and 2º10’ west. It is bordered to the west by Burkina Faso. It is one of the least developed in terms of infrastructure in the region. It is vast and mainly rural with a population density of about 32.8 persons per square kilometer, living in about 170 settlements grouped into eight sub- districts.

2.2. Study Design and Population

- This was across sectional study conducted in 2013 from the beginning of April to the end of May comprising of street cooked vendors in the Nadowli district.

2.3. Sampling, Data Collection and Statistical Analysis

- Four out of the eight sub-districts in the district were randomly selected from both densely and none densely populated areas of street food vendors based on the district assembly’s data base of trained and certified street food vendors after which 200 of them were randomly selected for the study. Face to face interviews were then conducted using a semi structured questionnaire. Data was entered, organize, cleaned and analyzed using Statistical Package for Social Scientists (SPSS) software version “20.0” (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois, USA)

2.4. Ethical Considerations

- Approval for this study was gotten from the Department of Community Health and Family Medicine of the School of Medicine and Health Sciences, University for Development Studies; Regional Health Directorate of the Upper West Region; District Health Directorate of Nadowli and the Nadowli District Assembly. Verbal consent was obtained from each street food vendor before data collection.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Demographic Characteristics

- In this study, majority (94.5%) of the food vendors were found to be females whiles the rest (5.5%) were males (table 1). This is consistent with what generally pertains in the developing world and especially in Africa where women tend to play very important roles in all street food vendor activities [18]. Similar findings were also observed in two earlier Ghanaian studies [10, 17]. Similarly, Comfort O. Chukuezi also found women preponderance amongst street food vendors in Owerri, Nigeria [21]. Studies done over a decade ago in Asia however found men to be more dominant in this industry [19]. A study in Nairobi, Kenya also found males to be about 60% of street vendor population which was is inconsistent with our findings [20].Majority of the food vendors where in the age group of 20-29 years whiles the least were found in the over 50 year’s age group (table 1). This finding is similar to that of other studies in Africa [5, 18, 20].In this study, majority (38.5%) of the population had junior secondary school education as opposed to two previous studies in Ghana which found those with senior secondary school education to be the majority [5, 18]. About 33% of the respondents were illiterates as shown in table 1. This was found to be consistent with those of other studies [17, 18]. On the other hand, some studies found a high literacy rate amongst street vendors a finding inconsistent with that of this study [5, 21].

3.2. Knowledge of Food Safety Practices

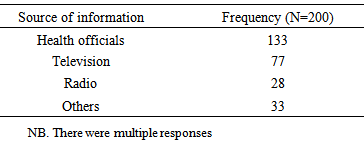

- Knowledge of food safety practices amongst respondents was 100% with their source of information shown in table 2.

|

|

3.3. Food Safety Practices

3.3.1. Personal Hygiene and Food Handling

- Poor personal hygiene especially non washing of hands with soap has been found to be associated with the transmission of bacteria pathogens amongst street food vendors [23]. Although a large proportion of vendors said they washed their hands after some major activities as illustrated in table 4, about 13% of them do not do that with soap, a finding very similar to that of an earlier study in a poor resourced community of Ghana [17]. Those who did not wash their hands with soap thought it was not necessary to do that whiles others also feared that the smell of the soap will be transferred to the food.

|

3.3.2. Water for Food Handling

- The main source of water for cooking was pipe borne (67%) while’s borehole (29%) and well (4%) water accounted for the rest. In a study conducted in an urban slum of Ghana, 99% of the water used for food vendor activities was pipe borne [17]. In Sudan pipe borne water accounted for about 60% of water used for food activities [22]. Pipe borne water however accounted for about 39% of water used for cooking in rural India [24]. Water used for cooking and other activities by vendors was found to be stored in bowls (73.5%), buckets (15%), both bowls and buckets (4.5%) and some other containers such as gallons, drums and pots (7%). These same containers were found to be used for other activities such as washing of cups and plates (54.4%), bathing (8.8%), both washing and bathing (8.8%) and other purposes such as storage of food stuffs (28%).

4. Conclusions

- Knowledge levels of food safety practices amongst street food vendors in this Northern rural setting was very high but however, this high knowledge was generally not translated into practice. We recommend that health officials, who serve as the major source of information on food safety issues to vendors, move beyond just educating and disseminating information to ensuring that food safety practices are adhered to. The regulatory authorities in the district should also enforce the laws on food safety practices.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- We are grateful to the Kaleo-Nadowli DHMT and district assembly for their immense assistance towards the conduct of this study. We also appreciate the support and cooperation of the Nadowli food vendors association.

References

| [1] | WHO. (1996). Essential safety requirements for street vended foods. Food Safety Unit, Division of Food and Nutrition, WHOIFNUIFOSf96.7. |

| [2] | FAO. Agriculture food and nutrition for Africa. A resource book for teachers of Agriculture. FAO, Rome. 1997: 123. |

| [3] | T. Rheinländer, M. Olsen, J. A. Bakang, H. Takyi, F. Konradsen, H. Samuelsen. Keeping Up Appearances: Perceptions of Street Food Safety in Urban Kumasi, Ghana. Journal of Urban Health: Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine 2008, 85 (6): 952-964. |

| [4] | World Health Organization (WHO) (1996). Food Safety Issues: Essential Safety Requirements for Street Vended Food (Revised edition). World Health Organization. Geneva. Available atwww.who.int/foodsafety/publications/fs_management/en/streetvend.pdf. |

| [5] | I. Monney, D. Agyei, W. Owusu. Hygienic Practices among Food Vendors in Educational Institutions in Ghana: The Case of Konongo. Foods 2013, 2, 282-294;doi:10.3390/foods2030282. |

| [6] | Canet C and C N’diaye. (1996). Street foods in Africa. Foods, Nutrition and Agriculture. 17/18. FAO, Rome, 18. |

| [7] | Chaulliac M and Gerbouin-Renolle P (1996). Children and street foods. Foods, Nutrition and Agriculture. 17/18. FAO, Rome. 1996:28. |

| [8] | A.M. Omemu, S.T. Aderoju (2008). Food safety knowledge and practices of street food vendors in the city of Abeokuta, Nigeria Food Control, Volume 19, Issue 4: 396-402. |

| [9] | A.H. Subratty, P. Beeharry, M. Chan Sun, (2004) "A survey of hygiene practices among food vendors in rural areas in Mauritius", Nutrition & Food Science, Vol. 34 Iss: 5, pp.203 – 205. |

| [10] | Mensah P, Yeboah-Manu D, Owusu-Darko K, Ablordey A. (2002). Street Foods in Accra, Ghana: How Safe are They? Bull World Health Organization, 80(7) Geneva. |

| [11] | Tortoe, C., Johnson, P -N. T., Atikpo, O. M., Tomlins K. I. Systematic Approach for the Management and Control of Food Safety for the Street/Informal Food Sector in Ghana. Food and Public Health 2013, 3(1): 59-67. |

| [12] | Obeng-Asiedu, P., Socio-economic survey of street vended foods in Accra, In: Enhancing the food security of the peri -urban and urban poor through improvements to the quality, safety and economics of street -vended foods. In Johnson, P. N. T and Yawson, R. M (Eds). Report on workshop for stakeholders, policy makers and regulators on street food vending in Accra. 25 - 26 September 2000, Food Research Institute, Accra, Ghana, pp. 20 – 23, 2000. |

| [13] | Laryea, J., Improvements to street food vending in Accra. Report on workshop for stakeholders, policy makers and regulators on street food vending in Accra. 25 - 26 September 2000. Food Research Institute, Accra, Ghana. pp. 23 – 27. 2000. |

| [14] | Tortoe, C., Johnson, P -N. T., Atikpo, O. M. Modules for managing Street/Informal Food Sector in Ghana. Food Research Institute/CSIR, Accra, Ghana. pp. 65. 2008. |

| [15] | Tomlins, K. I., Johnson, P. N., Obeng-Asiedu, P. and Greenhalagh, P., Enhancing the food security of the peri -urban and urban poor through improvements to the quality, safety and economics of street-vended foods. Final Technical Report, R No 7493 (ZB0199), NR International, Chatham, UK. pp. 76. 2001a. |

| [16] | Tomlins, K. I., Johnson, P. N. T. and Myhara, B., Improving street food vending in Accra: problems and prospects, In: Food safety in crop post harvest systems. In Sibanda, T. and Hindmarsh, P. (Eds). Proceedings of an international workshop sponsored by the Crop Post Harvest Programme of the United Kingdom Department for International Development. 20 -21 September 2001, Harare, Zimbabwe. pp. 30-33. 2001b. |

| [17] | Donkor E.S., Kayang B. B., Quaye J, Akyeh M. L, (2009). Application of the WHO keys of safer food to improve food handling practices of food vendors in a poor resource community in Ghana. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2009, 6, 2833-2842. |

| [18] | S. T. Odonkor, T. Adom, R. Boatin, D. Bansa and C. J Odonkor. Evaluation of hygiene practices among street food vendors in Accra metropolis, Ghana. Elixir Food Science 41 (2011) 5807-5811. |

| [19] | Bhat, R.V. and Waghray, K. (2000). Profile of street foods sold in Asian countries. In: Simopoulos, A.P. & Bhat, R.V. (eds.), Street foods. World Review of Nutrition and Dietetics. Basel: Karger, 86:53-99. |

| [20] | Muinde O. K, Kuria E (2005). Hygienic and sanitary practices of vendors of street foods in Nairobi, Kenya. African Journal of Food Agriculture and Nutritional Development (AJFAND): 5 (1): 1-14. |

| [21] | Comfort O. Chukuezi. Food Safety and Hygienic Practices of Street Food Vendors in Owerri, Nigeria. Studies in Sociology of Science 2010; 1(1): 50-57. |

| [22] | M. A. Abdalla, S. E. Suliman and A. O. Bakhiet. Food safety knowledge and practices of street food-vendors in Atbara City (Naher Elneel State Sudan). African Journal of Biotechnology Vol. 8 (24), pp. 6967-6971, 15 December, 2009. |

| [23] | Barro N, Bello AR, Savadogo A, Ouattara CAT, Ilboudo AJ, Traoré AS. Hygienic status assessment of dish washing waters, utensils, hands and pieces of money from street food processing sites in Ouagadougou (Burkina Faso). African Journal of Biotechnology Vol. 5 (11), pp. 1107-1112, 2 June 2006. |

| [24] | T. Reang, H. and Bhattacharjya. “Knowledge of hand washing and food handling practices of the street food vendors of Agartala, a north eastern city of India”. Journal of Evolution of Medical and Dental Sciences 2013; Vol. 2, Issue 43, October 28; pp. 8318-8323. |

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML