-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Food and Public Health

p-ISSN: 2162-9412 e-ISSN: 2162-8440

2013; 3(6): 341-345

doi:10.5923/j.fph.20130306.12

Dietary Awareness of Saudi Women with Gestational Diabetes

Ismail Eman Mohamed1, Ismail1, Mohamed Saleh2

1Nutrition and Food Science, Faculty of Home Economics, King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, 21488, Saudi Arabia

2(Current) Food Science and Human Nutrition, Faculty of Agriculture and Veterinary Medicine, Qassim University, Burridah, 51452, Saudi Arabia. (Permanent) Nutrition and Food Sciences, Minufiya University, Egypt

Correspondence to: Ismail Eman Mohamed, Nutrition and Food Science, Faculty of Home Economics, King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, 21488, Saudi Arabia.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) is a form of carbohydrate intolerance that was first recognized during pregnancy. The aim of this study was to find out the dietary pattern and health awareness of Saudi women with GDM. Two hundred thirty Saudi pregnant women between 21-44 years old in their 24 to 28 week of gestation, were randomly selected from private health centers in Jeddah city, Saudi Arabia. All subjects were screened for GDM and women with GDM were enrolled in the study. Data on socio demographic, health history, lifestyle, frequency of consumption of selected foods and beverages, meals number, regularity of breakfast, and relationship between some foods and diabetes were reported. Results revealed that 76 women were diagnosed as gestational diabetics; their mean fasting blood glucose was 174.2±31.3 mg/dl. The pregnancy frequency numbers for most of GDM women were 4 to 6 times (55.4%). About one third of subjects suffered from GDM in previous pregnancies, and diabetes mellitus is prevalent among 67.1% of their families. All subjects were eating not less than three meals per day and most of them eat three meals. Some of the women with GDM do not eat fresh vegetables, while 52.6% and 51.3% of them used to eat fresh fruits and citrus fruits respectively. The data revealed that 82.9% used to drink fresh fruit juice. In conclusion: Saudi women with GDM need dietary counseling, and nutritionists to suggest special dietary strategies for them.

Keywords: Gestational Diabetes, Diet, Pregnant, Women, Saudi Arabia

Cite this paper: Ismail Eman Mohamed, Ismail, Mohamed Saleh, Dietary Awareness of Saudi Women with Gestational Diabetes, Food and Public Health, Vol. 3 No. 6, 2013, pp. 341-345. doi: 10.5923/j.fph.20130306.12.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) is a form of carbohydrate intolerance of variable severity that is first recognized during pregnancy[1]. According to WHO GDM Gestational diabetes is hyperglycemia with onset or first recognition during pregnancy. Symptoms of GDM are similar to Type 2 diabetes[2]. GDM is associated with significantly elevated risk of short-term and long-term complications for both mothers and offspring[3 - 5]. Major risk factors for GDM include old age in pregnancy, and a family history of diabetes[4]. Modifiable factors include excess adiposity, physical activity, and diet[6]. GDM affects 1–14% of all pregnancies in USA[4] and its incidence is increasing with the increasing burden of obesity among women at reproductive age[7].Epidemiologic studies on the role of dietary factors in the development of GDM are at their early stage. However, the available data provide evidence that dietary factors may play a role in the development of GDM[6].Dietary components associated with GDM risk include macronutrients, micronutrients, and individual foods, such as refined carbohydrates, saturated and Tran's fats, heme iron, and processed meats[6]. Earlier studies suggested that macronutrient components of the diet in mid-pregnancy may predict incidence[8-10] or recurrence of GDM[6, 11]. Studies executed by Wang et al,[8] and Wijendran et al.,[11] suggested that polyunsaturated fat intake may be protective against glucose intolerance in pregnancy. A recent study showed that higher intake of fat and lower intake of carbohydrates may be associated with increased risk of GDM and impaired glucose tolerance[10]. Strong positive association was observed between the Western dietary pattern and GDM risk, whereas the prudent dietary pattern was significantly and inversely associated with GDM risk[13]. The prudent dietary pattern was characterized by a high intake of fruits, green leafy vegetables, poultry, and fish, whereas the Western pattern was characterized by a high intake of red meat, processed meat, refined grain products, sweets, French fries, and pizza[6]. The association with the Western pattern was largely explained by intake of red and processed meat products. Pre-gravid intake of red and processed meats were both significantly and positively associated with GDM risk, independent of known risk factors for type 2 diabetes and GDM.Pre-gravid consumption of dietary fiber (i.e., total, cereal, and fruit fiber) was significantly and inversely associated with GDM risk[13]. Each 10g/d increment in total fiber intake was associated with a 26% (95% CI: 9%, 49%) decrease in risk; each 5-g/d increment in cereal or fruit fiber was associated with a 23%[6, 14] or 26 %[3, 15] decrease, respectively.The intake of sugar-sweetened cola was positively associated with the risk of GDM, whereas no significant association was shown for other sugar-sweetened beverages and diet beverages[6].The aim of this study was to find out the dietary pattern and health awareness of pregnant Saudi women who suffer from gestational diabetes, and to highlight the relationship between food preferences and GDM.

2. Subjects and Methods

2.1. Subjects

- This study was carried out on 230 Saudi pregnant women in the 24 to 28 gestation, between the ages of 21 and 44, they were randomly selected from private health centers in Jeddah city, Saudi Arabia. For ethical consideration all selected women were informed about the objectives and proposal of the study, and those who agreed to participate gave written consent. Also the selected women completed a socioeconomic questionnaire before being subjected to diagnosis of gestational diabetes.

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. Diagnosis of Gestational Diabetes

- All selected women screened for GDM at 24–28 wk. of gestation with a 50-g glucose load[1]. Women with a positive result underwent a 100-g oral-glucose-tolerance test (OGTT). Blood samples were collected 1 h after the 50-g glucose load and 0, 1, 2, and 3 h after the 100-g OGTT. Those with positive results from the OGTT received a diagnosis of GDM (Metzger, 1991). Seventy-six women with GDM participated in the study.

2.2.2. Non-dietary Factors

- Information on sociodemographic, health history, family history of diabetes mellitus, and lifestyle were collected. Obesity was identified by self-reported body weight. Moreover, data related knowledge of the meaning of diabetes, diabetes complications, normal blood glucose level, signs and complications of diabetes, diabetic ketoacidosis, causes of diabetes, effect of GDM on the ability of diabetic women of childbearing were collected. Finally, fasting blood glucose (mg/dl) was determined for all GDM subjects.

2.2.3. Dietary Factors

- Information about the average frequency of consumption of selected foods and beverages during the previous year were reported. Also information about meals number, regularity of breakfast, and relationship between some foods and diabetes were reported.

2.2.4. Statistical Analyses

- All statistical analyses were made by SPSS software (version 16; SPSS Inc.). Results presented as means with SDs for numeric variables and frequency with percent for string variables.

3. Results

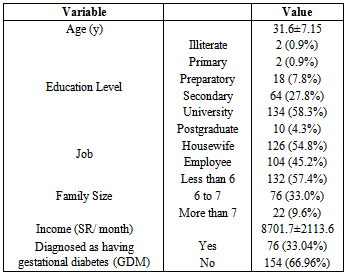

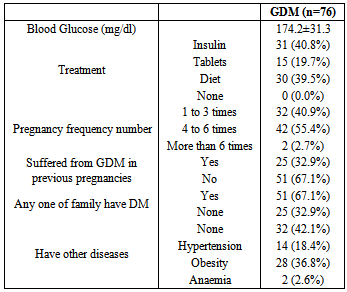

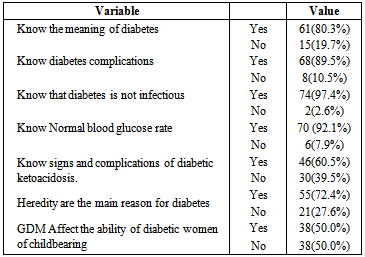

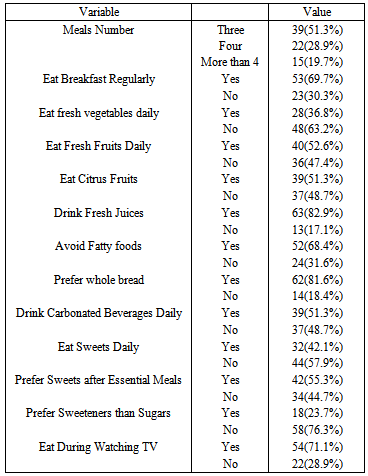

- Table 1 Data related to characteristics of women with and without gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM).

|

|

|

|

4. Discussion

- As shown in Table 1 the mean age for all subjects was31.6±7.15y and most subjects got university degree (58.3%) or secondary education (27.8%). While, 45.2% of subjects were housewives and the families' size for the majority (57.4%) were less than six persons. The mean income for all subjects was 8701.7±2113.6 Saudi Riyal. The most interesting findings in this study was that 76 (66.1%) of studied subjects were diagnosed as gestational diabetics, which represent high prevalence of gestational diabetes among Saudi women. This was due to the tendency of the researchers to choose women with gestational diabetes and this will not reflect the normal prevalence among Saudi women. However, very little data is available from the Gulf Area with regard to the prevalence of gestational diabetes mellitus.The mean fasting blood glucose levels for GDM women was 174.2±31.3 mg/dl (table 2). The majority of women were treated with either insulin (40.8%) or diet (39.5%), and the pregnancy frequency numbers for most of them were 4 to 6 times (55.4%). About one third (32.9%) of the studied women suffered from GDM in previous pregnancies, and diabetes mellitus was prevalent among 67.1% of their families. Although 42.1% did not have other, diseases but 36.8% and 18.4% had obesity and hypertension respectively.Data showed that 80.3% of subjects knew the meaning of diabetes; while 89.5% were aware of its complications. In addition, 60.5% of the subjects knew the signs and complications of diabetic coma. Half of subjects (50%) think that GDM affect the ability of diabetic women of childbearing.Few studies have examined diet before and/or during pregnancy in association with GDM risk. In this study, the authors tried to highlight the role of food pattern and habits on GDM. As show in table 4, none of the studied subjects eat less than three meals per day and most of them eat three meals (51.3%) or more (48.7%). Although 69.7% eat breakfast regularly but still considerable percentage, (30.3%) used to skip it. Although low percentage of women in this study eat fresh vegetables (36.8%), more than half were eat fruits, and 82.9% drink fresh fruit juice, but we courage this trend which might be favourable and could be beneficial for GDM women. However, in their observational study in 10 Mediterranean countries on 1076 consecutive pregnant women, Karamanos et al. 2013[22] found that adherence to a Mediterranean Diet pattern of eating (that pattern rely mainly on vegetables and fruits) is associated with lower incidence of GDM and better degree of glucose tolerance, even in women without GDM.Unfortunately, we noticed that women in this study were not keen or accustomed to consume fresh vegetables and fruits that may be due to the western pattern, which became common in Saudi population. Factor analyses in the Nurses’ Health Study II identified two dietary patterns, the Western pattern and the prudent pattern, Strong positive associations were observed between the Western dietary pattern score and GDM risk, whereas the prudent dietary pattern score was significantly and inversely associated with GDM risk[16]. The prudent dietary pattern was characterized by a high intake of fruit, green leafy vegetables, poultry, and fish, whereas the Western pattern was characterized by a high intake of red meat, processed meat, refined grain products, sweets, French fries, and pizza[17]. It seems that mentioned food pattern in this study agreed with that observed by Ali et al., 2013[23] who found in their study on food knowledge among GDM women in UAE that women with GDM reported significantly lower intake of fruits and fruit juices (P = 0.012) and higher consumption of milk and yogurt (P = 0.004). Furthermore, they concluded that their results highlight the urgent need to provide nutrition education for women with GDM in the UAE.The majority of women with GDM in this study avoided fatty foods (68.4%) and use vegetable fats in cooking. This trend might be healthful where some studies[8, 9, 12] suggested that polyunsaturated fat intake maybe protective against glucose intolerance in pregnancy, and high intake of saturated fat may be detrimental. A recent prospective study considered the correlation of nutrients with GDM showed that higher intake of fat and lower intake of carbohydrates might be associated with increased risk of GDM and impaired glucose tolerance[10].It was well known that Saudi population prefer meats and consume high amounts from red meat. Zhang and Ning,[6] reported that pregravid intake of red and processed meats were both significantly and positively associated with GDM risk.As shown in table 4, 81.6% of women preferred to eat whole bread; it was evident that consumption of dietary fiber was significantly and inversely associated with GDM risk[18].Unfortunately, it was found that considerable percent of GDM women in this study still consume sugars in the form of carbonated beverages, sweets, and drinks. In animal models and human studies, a high-sugar diet decreases insulin sensitivity[19,20] and insulin secretion[21].

5. Conclusions

- Dietary treatment/counseling has long been recommended for Saudi women who develop GDM. Moreover, the nutritionists need to suggest special dietary strategies for women with gestational diabetes.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML