-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Food and Public Health

p-ISSN: 2162-9412 e-ISSN: 2162-8440

2013; 3(6): 329-335

doi:10.5923/j.fph.20130306.10

Dietary Intake of Nutrients Related to Bone Health among Alexandria University Female Students, Egypt

Dalia Ibrahim Tayel, Ali Khamis Amine, Amina Klifa El

Nutrition Department, High Institute of Public Health, Alexandria University, Egypt

Correspondence to: Dalia Ibrahim Tayel, Nutrition Department, High Institute of Public Health, Alexandria University, Egypt.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

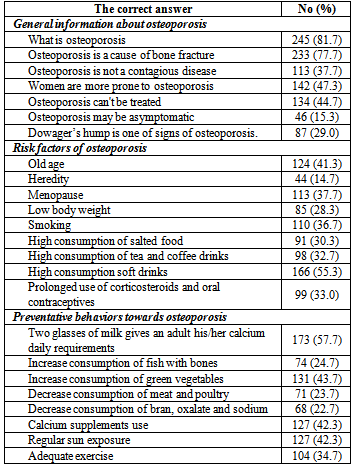

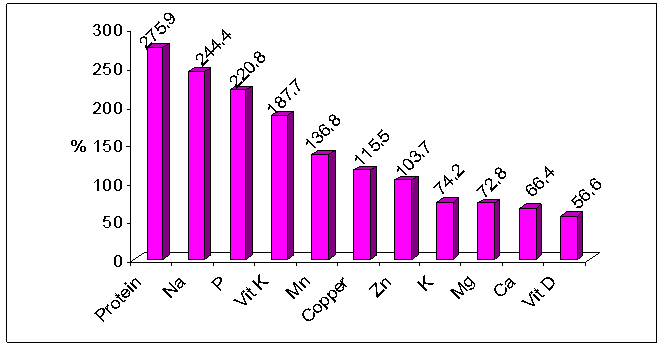

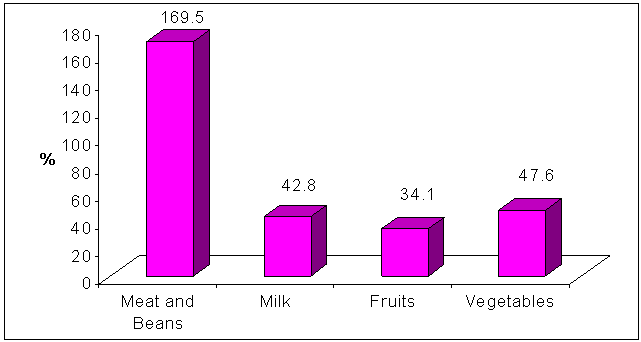

The study aimed to assess the dietary intake of nutrients related to bone health and to assess female university students' knowledge and dietary practices related to osteoporosis. A cross sectional study was conducted on 300 apparently healthy female students; they were selected at random from some faculties of Alexandria University. Data was collected about socio-demographic characteristics, medical history, dietary pattern, life style practices, and knowledge toward bone health and osteoporosis. Weight and height were measured. Dietary intake and adequacy of calcium were 685.67±224.51 mg/day and 66.4%, respectively. Relative to dietary reference intake (DRI), Alexandria University female students consumed insufficient intakes of vitamin D, magnesium and potassium (56.6%, 72.8% and 74.2%, respectively); and excess intakes of protein, sodium and phosphorus (275.9%, 244.4% and 220.8%, respectively). Most of the female students practiced the dietary habits which may be considered as dietary risk factors for osteoporosis. The females had poor knowledge about risk factors and preventive behaviors towards osteoporosis. It is concluded that Alexandria University female students are at high risk of osteoporosis later in life. Public health strategies should aim to improve the calcium intake of females in this age, and to reduce the risk of osteoporosis through lifestyle modifications.

Keywords: Osteoporosis, Nutritional Knowledge, Young Adult Females

Cite this paper: Dalia Ibrahim Tayel, Ali Khamis Amine, Amina Klifa El, Dietary Intake of Nutrients Related to Bone Health among Alexandria University Female Students, Egypt, Food and Public Health, Vol. 3 No. 6, 2013, pp. 329-335. doi: 10.5923/j.fph.20130306.10.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Osteoporosis has a serious public health concern. Osteoporosis cause significantly negative impact on demand for health services and on people‘s physical, psychological health and quality of life.[1] Osteoporosis is a progressive systemic skeletal disease, proceeds silently without any significant symptoms, characterized by reduced bone mass density.[2] A bone mineral density test is used in the diagnosis for osteoporosis. The treatment of osteoporosis includes medications, calcium and vitamin D supplementation, adequate diet, a regular and adequate exercise and a healthy life style.[3] Both genetic and behavioral risk factors contribute to the development of osteoporosis. Genetic risk factors include race, gender, diminished estrogen levels after menopause, thinness, small frame, and hereditary. Behavioral risk factors include alcohol and caffeine consumption, calcium deficient diet, and sedentary lifestyle.[4] Women are more at risk than men; this is attributed to the fact that fewer men have low levels of bone density as compared to women.[5]During adolescence and early adulthood, women need to increase the intake of foods rich in calcium and other nutrients that have positive effect on bone health to build peak bone mass and to reduce the risk of developing osteoporosis.[6] A progressive loss of bone with aging causes bones to be more susceptible to fracture later in life. In this respect, osteoporosis is recognized to be a “pediatric disease with geriatric consequences”.[7] Calcium is a mineral needed by the body for healthy bones. Bones act like a calcium bank storing and releasing it into the blood stream when needed. Therefore, bone is at risk of losing its strength when calcium intake is insufficient. After age thirty, the cells that build bone are not as efficient and bone is gradually lost and begins to break down.[8, 9]Protein is incorporated into the organic matrix of bone. Chronic low protein intake contributes to low level of serum calcium and increasing bone desorption of calcium. High protein diet may increase risk of osteoporosis as a result of increase urinary calcium excretion.[10] Phosphorus is an essential nutrient in bone growth and mineralization, but excess amounts may be detrimental to it due to increased parathyroid activity, possibly resulting in bone loss.[11]Magnesium is essential for bone formation due to the activation of vitamin D form to increase calcium absorption. Manganese is essential for mineralization of bones and production of connective tissues. Zinc present in the mineralized component of bone (osteoblast). It is essential for several critical enzymes required for bone metabolism to help in forming of the optimal bone matrix. Copper is needed in cross linking of both collagen and elastin. Boron can enhance calcium absorption because it may have action similar to estrogens on bone. Vitamin K is involved in bone health because of its function in the carboxylation of osteocalcin. A low potassium diet causes elevated urine calcium. A high salt diet has been suspected of being detrimental to bone health due to the increase urinary calcium excretion by sodium.[12]The purpose of the study was formulated to determine the dietary intake of calcium and other nutrients related to bone health among female students in Alexandria University and to assess their knowledge and dietary practices related to osteoporosis.

2. Subjects and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Sampling

- A cross sectional approach was used to conduct this study from Feb to Jun 2012 on 300 apparently healthy female students of Alexandria University from the faculties of Arts, Education and Commerce. Female students that complained from bone disease or had clinical signs of bone disease which preventing them from being normal physically active, those who were on strict diet involving special meals, and those who had any medical background were excluded from this study. Sample size was determined based on the assumption that the mean intake of dietary calcium for adult female was 618.9±20 mg/day,[13] and using Epi Info "6.04" (CDC, USA), a power of 80% and α =0.05 with 5% level of significance. The study subjects were selected at random using systematic random sampling technique from all female students with inclusion criteria and accepted to participate in this study.

2.2. Data Collection

- A pre-designed structured interview questionnaire was used to collect data about socio-demographic characteristics (age, marital status and place of residence); medical history (family history of osteoporosis, the prolonged use of the drugs such steroids or anticonvulsant or others medications as use of calcium supplements, age at menarche, menstrual regularity and length of menstrual cycle); dietary habits (skipping meals, eating snacks between meals, eating outside the home, and regular consumption of caffeinated beverages (e.g. tea, coffee and carbonated soft drinks); life style practices (smoking and physical activity); and knowledge on bone health and osteoporosis. Physical activity was assessed and expressed by frequency (days/week) and duration of activity (min/week) for each activity including walking transportation tool, studying, sport practicing and household tasks (e.g. washing by hand, sweeping floor and child-care duties).Knowledge on bone health and osteoporosis was obtained by 24 questions, 7 questions assessing general information about osteoporosis (prevalence among both sexes, signs and symptoms of osteoporosis, risk factors and presence of treatment); 9 questions assessing risk factors of osteoporosis (menopause, old age, smoking, consumption of soft , tea and coffee drinks and consumption of high protein and salted foods); and 8 questions assessing dietary lifestyle preventive behaviors of osteoporosis (taking calcium supplements, consumption of dairy products and green vegetables, sun exposure and exercise). Questions were scored so that wrong answer was scored (0), don’t know (1) and correct answer was (2). Questions were scored and calculated with a total maximum score of 48 were distributed as 14 for the section on general information about osteoporosis, 18 for risk factors section and 16 for dietary lifestyle preventive behaviors section. Knowledge was categorized so that <60% of the total score was considered as poor knowledge, 60-80% fair knowledge and ≥80% good knowledge.Data regarding food intake was collected from every participant at the time of interview. Food frequency questionnaire was used to estimate the dietary intake and the pattern of consumption of different foods most commonly consumed by university female students with special emphasis on special foods rich in calcium, phosphorus, magnesium, zinc, manganese, copper, sodium, potassium, vitamins D and K and protein (e.g. milk and dairy products, soy-based foods, vegetables and fruits, egg, canned sardine and other animal-based products, salted fish, pickles).[14] The quantities of foods and drinks consumed were estimated using common household utensils as cups and plates. The consumption of food was considered high if the food item was consumed ≥ 3 days per week and if it was consumed < 3 days per week, the consumption of this food was considered low. Mean daily intake of different food groups in grams was compared with the recommended serving units of My Pyramid[15] after conversion of each serving unit from each food group into grams. The nutritive value of the daily diet was computed using the Egyptian Food Composition Tables.[16] Nutrient adequacy percent was calculated and compared with dietary reference intake (DRI)[17] of young females as the following: percentage adequacy of nutrient = (nutrient intake for university female students / DRI of nutrient) × 100. Weight and height measurements were carried out for each participant at the time of interview. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated according to the following equation: weight in kg / height in meter2 (kg/m2). If female aged > 19 years, she was considered obese when BMI was ≥ 30 kg/m2, overweight when BMI was 25-29.9 kg/m2, and underweight when BMI was < 18.5 kg/m2.[18] If female aged ≤ 19 years, she was considered obese when BMI was ≥ 95th percentile BMI-for-age, overweight when BMI was ≥ 85th and < 95th percentile BMI-for-age, and underweight when BMI was ≤ 5th percentile BMI-for-age. WHO (2007) reference data of BMI-for-age percentiles were used.[19]

2.3. Statistical Analysis

- After completion of data collection, data were revised, coded and fed to the computer using the Statistical Package for Social Science software (SPSS) version “17” (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois, USA) for tabulation and analysis. Data was presented tabular, graphically and mathematically as number and percent and also using mean and standard deviation (SD).

2.4. Ethical Considerations

- There were no conflicts of interest. This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors. This study was conducted according to the guidelines laid down for medical research involving human subjects and was approved by the ethics committee of the High Institute of Public Health, Alexandria University, Egypt. All measurements were taken in full privacy and the collected data were kept confidential. All female students were informed about the objective of the study and they had the right to accept or refuse to participate in the study, then their verbal consent was obtained.

3. Results

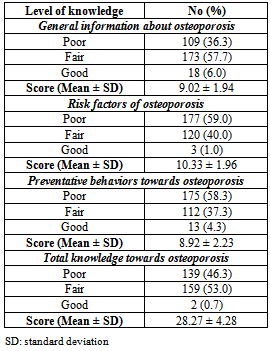

- A total of 300 female students of Alexandria University participated in the present study aged between 18-25 years with mean age 21.65±3.66 years. The majority of the studied sample was single (98.3%) and living in urban residence (98%) (Table1). Mean age at onset of menarche was 12.33±2.56 years, and mean length of the menstrual cycle was 26.81±4.45 days.Table 1 also reveals that 53.3% of the studied students never skip any meals while 18.7% of them skipped breakfast and 17.7% skipped lunch. The majority of females in the studied sample usually eat snacks between meals (93%) and usually eat outside their homes (84.7%).Table 2 shows mean daily intake of nutrients related to bone health for the studied sample, while Figure 1 shows mean nutrients adequacy for the studied sample relative to DRI of the studied group. It appears clearly from the table and the figure that the nutrients intakes of Alexandria University female students from protein, sodium, phosphorous, vitamin K, manganese, copper and zinc were more than their requirements. While the intakes of potassium, magnesium, calcium and vitamin D were less than the daily requirements of the studied sample.

|

|

| Figure 1. Adequacy of nutrients related to bone health |

| Figure 2. Intake of different food groups relative to serving units of My Pyramid |

|

|

|

4. Discussion

- Bone is a living organ and just like any other organ in our bodies, same measures could be taken to keep the bones strong and healthy. Calcium is vital for strong teeth and bone because it gives them strength and rigidity.[20,21] Healthy young women should be aiming to consume 1000 mg calcium per day.[17] Insufficient intake of calcium may result in weak bones, especially for women who have a greater risk of osteoporosis later in life.[22] In the present study, most of the studied sample (91.3%) consumed calcium less than their recommended daily requirements (adequacy 66.4%). This is in accordance with the particular concern that young women are not getting the calcium they need, that make their bones at high risk.[23] On the average, the calcium consumption of women fell significantly below the requirements.[24,25] This low dietary intake of calcium was due to low consumption of calcium rich sources such as milk and yogurt, soybean products, green leafy vegetables and canned fish which eaten with its bone. This goes along with the results of other studies.[26, 27]Other factors that contribute to increase the risk of osteoporosis are increased consumption of foods rich in enhancers to calcium desorption such as protein and sodium (soft and caffeinated drinks, pickles, pulses, and meat and meat products).[28] an adequate protein intake is important for supporting bone growth. However, increasing intake of dietary protein, particularly animal protein, is associated with increased urinary calcium losses that may result in increased bone desorption and osteoporosis.[29] The vegetables and fruits are rich in bone building and alkalizing nutrients.[6] In this study, the dietary intake of protein for university female students was more than double their requirements according to DRI of the same age group (adequacy 275.97%). In the same time, the consumption of fruits and vegetables were less than the recommended by My Pyramid (34.1% and 47.6% respectively). This indicates that the high protein intake was due to the high consumption of animal sources (meat and meat products) which may have negative effect on calcium level and bone health.Low consumption of green vegetables and fruits that contain high amount of useful minerals like potassium and magnesium for calcium absorption and promote calcium retention and also they are essential for normal bone formation due to the activation of vitamin D (the enhancer of calcium absorption).[30] When potassium and magnesium intake are low - as in the results of this study - bone development can be impaired.[6]Also the foods rich in enhancers to calcium desorption interfere with calcium absorption due to their content of phosphorus when consumed in high amount.[11] another mineral that is very important for bone health is phosphorus. Balancing phosphorus with calcium intake is necessary for bone mineralization. It is well known that soft drinks – even diet soft drinks – are bad for bone health. This is because they often contain phosphoric acid, especially cola. Lots of phosphorus coming in the body can bind calcium (leaving less amount of it for bones), stimulate parathyroid hormone, and diminish active vitamin D formation.[31] In the present study female students showed high consumption of the phosphorus containing drinks (tea, cola and coffee) and excessive phosphorus intake more than the recommended. High consumption of salty foods like chips with high content of sodium interferes with calcium and increase urinary calcium excretion. From the results of this study, it was clear that sodium intake more than the recommendations. This may be due to high consumption of salty foods (pickles) which is a common habit of Egyptians and also the high consumption of processed foods and drinks that mainly use sodium salt as a preserver such as processed cheese, soft drinks and canned juices. Because calcium was retained by the body in the presence of sodium, bones became thin and at risk of osteoporosis.[32] Eating outside the home, skipping meals and eating snacks were common unhealthy dietary habits among Alexandria University female students, because they spent long time at the university and eating apart from their families that supervise the eating. Poor eating habits may also be the main cause of low dietary intake of almost nutrients that have an effect on bone health.Low women's level of knowledge about osteoporosis is well documented although a majority of the studies have been in pre- or post-menopausal women. Women's knowledge principally about a sedentary lifestyle and low calcium intake as risk factors of osteoporosis was consistently high.[33,34] The present study revealed that both poor knowledge of university female students and unhealthy dietary intake of nutrients related to bone health indicated the need for future educational program that would help to raise awareness, knowledge and belief of university female students towards osteoporosis specially as regard risk factors of osteoporosis and preventive behaviors towards osteoporosis. This is in accordance with that the previous reports that osteoporosis educational programs have the potential to influence the behaviors conducive to healthy bone.[35,36]

5. Conclusions and Recommendations

- Because osteoporosis has a serious public health concern and women are more at risk than men, detection of osteoporosis risk factors and the prevention procedures should be started during adolescence and early adulthood. Alexandria University female students are at high risk of osteoporosis and bone diseases due to insufficient dietary intake of calcium (intake and adequacy of calcium are 685.67±12.96 mg/day and 66.37%, respectively); insufficient dietary intake of vitamin D, magnesium and potassium (56.60%, 72.83% and 74.21%, respectively); excessive dietary intake of protein, sodium and phosphorus (275.97%, 244.38% and 220.83%, respectively); poor knowledge about risk factors and preventive behaviors towards osteoporosis (59 and 58.3%, respectively); bad and unhealthy dietary habits and lifestyle practices related to osteoporosis and bone health (such as low or no consumption of calcium rich foods (milk and milk products, soybean based foods, canned fish which eaten with its bone and green leafy vegetables) and high consumption of foods and drinks containing inhibitors of calcium absorption or enhancing calcium desorption as protein and sodium (soft and caffeinated drinks, pickles, pulses, and meat and meat products).Public health program should be implemented to improve the calcium intake of females in this age, and to reduce the risk of osteoporosis through lifestyle modifications. Comprehensive nutritional educational programs about the problem ought to be developed and implemented for females at age of university to increase consumption of calcium containing foods (as milk and its products, soybean based foods, fish which eaten with its bone and green leafy vegetables); decrease consumption of foods and drinks that containing inhibitors of calcium absorption (as soft drinks, tea and coffee drinks, processed foods and juices, pickles and salted foods and animal based foods); increase consumption of potassium and magnesium containing foods (as fruits and vegetables); and performing regular and adequate exercise at least five days weekly.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML