Olufunke M. Ebuehi1, Onime Linus Ailohi2

1Reproductive and International Health Unit Department of Community Health and Primary Care College of Medicine, University of Lagos Lagos, Nigeria

2National Open University of Nigeria, Lagos, Nigeria

Correspondence to: Olufunke M. Ebuehi, Reproductive and International Health Unit Department of Community Health and Primary Care College of Medicine, University of Lagos Lagos, Nigeria.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

Abstract

Genetically modified (GM) food/organism is a product of recombinant DNA biotechnological procedures which allow the genetic constitution of an organism to be modified for specific ends such as: nutrient fortification, faster growth, improved organoleptic characteristics, and resistance to pesticides, amongst others. The study assessed the knowledge, attitude and consumption practices of GM foods among 318 undergraduate medical and dental students of the University of Lagos, using a pre-tested, self-administered questionnaire. Data were analysed using EPI-INFO version 6.4. Approximately half (53.1%) of the respondents were females and 46.9% were males with mean age of 21.3 ± 2.67 years. Awareness about biotechnology and GM foods/organisms was high (87.3% and 72%, respectively). However, knowledge regarding specific details about GM technology was poor. Less than one-quarter (16.7%) had good knowledge about GM foods while approximately four-fifths (83.6%) of them had negative attitude toward GM products. Gender (p=0.0008) and course of study (p=0.0002) were significantly associated with knowledge levels. Similarly, knowledge was significantly associated (P =0.0066) with the attitude of respondents towards GMFs/GMOs. Attitude also significantly influenced choice between traditional and GM foods if the prices are the same (p=0.003) and choice if price is different but quality is the same (p=0.018). In conclusion, the study revealed that undergraduate medical and dental students of the University of Lagos, although were aware of GM products, however knowledge about specific details concerning GM technology was poor, attitude was largely negative, with a large proportion of respondents expressing concerns of safety and protection of consumers’ rights. This expectedly influenced their preference for traditional (organic) foods over GM foods. A more inclusive approach, comprising of a comprehensive enlightenment of young adults about the GM technology detailing its components, challenges, opportunities and prospects in addressing the global food crisis is recommended.

Keywords:

Genetically Modified Foods, Traditional/Organic Foods, Medical, Dental Students

Cite this paper: Olufunke M. Ebuehi, Onime Linus Ailohi, Genetically Modified (GM) Foods/Organisms: Perspectives of Undergraduate Medical and Dental Students of the College of Medicine, University of Lagos, Lagos, Nigeria, Food and Public Health, Vol. 2 No. 6, 2012, pp. 281-295. doi: 10.5923/j.fph.20120206.14.

1. Introduction

Genetically modified (GM) foods are those whose original DNA structures have been changed. DNA is the basic blueprint of each living thing. By altering the DNA, the characteristics or qualities of a living organism (in this case, plant) can be changed. 1One of the ultimate aims of genetically modifying plants includes the need to make plants like soybeans or corn resistant to the herbicides used in the fields. As such, when the fields are sprayed with the herbicides, all the weeds are killed but not affecting the actual crops.[1, 2]Other concepts that have surfaced recently include the delivery of ‘edible vaccines,’ made possible when a gene with vaccine potential (e.g., a viral surface antigen) is introduced into tomato or potato plants. The aim is to deliver low-cost vaccines to remote, inaccessible places in, for example, rural Africa. 3In the theoretical sense, this makes a good model for the farmer who is trying to grow more crops and wants to avoid damage from the weeds. However, issues associated with genetically modified organisms/foods may not be that simple.Man has been manipulating life forms since husbandry and agriculture began. In the search for new crops and varieties that are more productive, farmers started to modify plants some 10,000 years ago.3 Their methods were, however, slow and trial-and-error. 1 Following discovery by James Watson and Francis Crick of the molecular structure of DNA in 1960s, and from the early seventies, biotechnologists have learned more ways of introducing genes to plants and animals with much greater precision and from species other than that of the host. Although by crossbreeding and selection most domesticated and cultivated species have been changed radically from their wild forebears, technology which became referred to as ‘genetic engineering’ or ‘recombinant DNA (r-DNA) technology’ allowed the incorporation of novel characteristics which traditional breeding cannot achieve. The term ‘genetically modified’ came to refer to matter that carries genes introduced by ‘gene splicing’. 3With the discovery of fundamental genetics, organisms have been selected to express a range of required traits. Hence, new animal strains, plant varieties and hybrids have been produced.3Before the advent of genetic engineering, plant and animal breeders combined large blocks of genes by mating individuals with differing desirable traits. Then backcrossing and selection eliminated the undesirable traits. More recently however, plant breeders have irradiated seeds to encourage mutation.[2, 3] First-generation genetically modified (GM) foods were designed to provide growers with alternative crop management solutions.3 Here, selected genes were identified from plants and other sources and then transferred to the crop plant. In the agrifood sector, first generation biotechnology products have been crops with improved agronomic traits, such as herbicide tolerance and resistance to particular insect pests.[4, 5] Subsequent modifications provided traits such as enhanced nutrition or health promoting characteristics.Second-generation bioengineered crops incorporated additional novel agronomic traits (e.g. disease resistance, stress tolerance and improved yields) but also enhanced quality traits. Novel quality traits will permit the production of better animal feeds (e.g., high energy or nutrient density), foods with healthier nutritional and improved organoleptic properties, enhanced feed stocks (e.g. oils, starches and other polymers) for industrial and pharmaceutical uses, enhanced nutritional and pharmaceutical agents (e.g. neutraceuticals) and various other products. Industrial and pharmaceutical applications create entirely new economic possibilities and value.[5, 6]Examples of second generation GM foods are oil seeds with improved fatty acids, minerals; high-amylose maize; staple food with enhanced content of essential amino acids, minerals, vitamins; and GM functional foods with diverse health benefits.[6, 7]Enhancing food crops with higher nutrient content through conventional GM breeding is also called bio-fortification.8 A well-known example of a GM bio fortified crop is Golden Rice—also called New Rice for Africa (NERICA)—which contains significant amounts of provitamin A. Other bio-fortified projects include the development of GM sorghum, cassava, banana and rice enhanced with multiple nutrients.8 Such crops may become commercially available over the next 5-10 years.Third generation GM crops involve molecular farming where the crop is used to produce either pharmaceuticals such as monoclonal antibiotics and vaccines or industrial products such as enzymes and biodegradable plastics.[9, 10] Although concepts have been proven for a number of these technologies, product development and regulatory aspects are even more complex than they are for first- and second-generation crops. Substances produced in the plant must be guaranteed not to enter the regular food chain with a zero-tolerance threshold. Therefore, plants that are not used for food and feed purposes will likely be chosen for product development, or approval for third-generation GM crops will be given for use under contained conditions only.In any case, this brief overview reveals that the GM foods available so far represent a relatively minute fraction of the large future potentials of genetic engineering. Since the release of the first genetically modified crop into the marketplace in the 1990’s, there has been continuing debate over the acceptability of such products. Genetically modified organisms (GMOs) manufactured through bioengineering have raised economic, ethical, moral and environmental issues. 11Beside the advantages and prospects highlighted above, there equally appears to be a great number of scientists, social commentators and activists who feel dubious about GMOs and what they represent. In the same vein, some studies have revealed that GM DNA fragments could survive processing and intestinal digestion, while others have been found in milk and meat from animals fed with GM foods. While a large majority of the world’s population has embraced genetically modified (GM) pharmaceuticals and vaccines, a significant portion of the world’s population has expressed reservations about the creation of agricultural food and fibre products using genetic engineering technologies. 11 Similarly, many people believe that biotechnology will bring irreversible damage to the world. This voice of opposition comes mostly from environmental, consumer and religious groups. To these groups of people, the risks posed by biotechnology outweigh the benefits. Insufficient information and lack of confidence in the public sector’s ability to properly regulate biotechnology further complicates the situation. This makes perception to be one of the biggest issues confronting the large scale introduction of GM technology. In a study of lecturers’ perception towards consumption of genetically modified foods in Nigeria and Botswana, Oladele and Subair observed that there was significant difference between lecturers from the two countries (Z = –6.65, p < 0.05); with higher mean rank for Botswana (108.02) than for Nigeria (58.01). Lecturers from BCA agreed and were positively disposed to 12 (80%), while lecturers from south western universities in Nigeria agreed and were positively disposed to five out of the 15 statements (33.3%) on the rating scale.12 However, in a related study on “Knowledge and Perception of Genetically Modified Foods among Agricultural Scientists in South-West Nigeria,” most of the respondents perceived that GM has no negative effect on the environment and were therefore, in support of the introduction of GM foods in Nigeria. 14 Another survey indicated that only one-in-five Nigerians (20 percent) were aware that genetically modified food products are currently on sale in supermarkets; about one-fifth (22 percent) believe that creating hybrid plants through genetic modification is morally wrong, even as majority (70 percent) of Nigerians, however, did not view such practices as being immoral. 14Unlike in many other countries where there are enabling laws guiding the use, planting, packaging, selling and consumption, at the moment, there are no regulations on the use of GMOs in Nigeria, although it is presently being considered—under the Biosafety Bill currently under consideration at the National Assembly—due to the proclaimed advantage of ensuring food security through biotechnology. Marketing of GMO-derived food products places a responsibility on each contributing side such as researchers, academics, research organizations, policy-makers, legal authorities, private companies, farmers and even the consumers, who have to weigh the pros and cons vehemently expressed by supporters and antagonists of GMOs. Several surveys have been conducted to determine public perception of GMOs in the USA, Europe and elsewhere. However, very few surveys have been conducted to assess GMOs perception in developing countries-Nigeria inclusive. Apart from studies conducted by Abubakar, A. A. on awareness of genetically modified food (biotechnology) among higher socio-economic and educated group (men and women) within the three major tribes (Igbo, Hausa and Yoruba) in Nigeria, 14 and another in 2008 by Oladele and Subair on perception of university lecturers towards consumption of genetically modified foods in Nigeria and Botswana, 12, it is difficult to ascertain the existence or otherwise of other studies, particularly among young adults in Nigeria. As future custodians of public health, exploring medical and dental students’ knowledge, attitude and consumption practices of GM foods may provide an understanding of their perspectives on this issue, more so when concerns about the health risks associated with GM foods are widely debated. Given the global food shortage and widespread hunger in developing countries, the high cost of food and the effects of malnutrition on public health vis-à-vis the hopes that GM hold for the future and the numerous arguments that have arisen, it is important to assess the knowledge, attitude and consumption practices among a peculiar sub-set of the Nigerian youth population (undergraduate medical and dental students of the College of Medicine, University of Lagos)-who by virtue of their undergraduate training, should be abreast of contemporary issues in health including nutrition-related issues. It is important to assess what the students think of the two major reasons always posited for the use of GM foods: the first being that tinkering with the building blocks of life is essential if we are to feed the world’s burgeoning population, and secondly, that through their use we can decrease the amount of pesticides applied to crops, some of which inevitably ends up in our water and on our plates (i.e., the pesticides are leached into water bodies, and retained in the plants even up to the point of preparing and serving them) —with the term pesticide meaning both insecticide and herbicide).13 Suffice to add that some studies have equally revealed that GM DNA fragments could survive processing and intestinal digestion, while others have been found in milk and meat from animals fed with GM foods.[13, 14]

2. Methodology

2.1. Background to the Study Area

Lagos state is located on the south-western part of Nigeria on the narrow coastal flood plain of Bight of Benin. It lies approximately on longitude 20 420E and 3 220E East respectively and between latitude 60 220N. It is bounded in the North and East by Ogun State of Nigeria, in the West by the Republic of Benin, and in the South by the Atlantic Ocean. It has five administrative divisions of Ikeja, Badagry, Ikorodu, Lagos Island and Epe. Territorially, Lagos state encompasses an area of 358,862 hectares or 3,577sq.km.Although Lagos state is the smallest state in Nigeria, with an area of 356,861 hectares of which 75,755 hectares are wetlands, yet it has the highest population, which is over five per cent of the national estimate. 15 The state has a population of 17 million. 15 The UN estimates that at its present growth rate, Lagos state will be third largest mega city in the world by the year 2015, after Tokyo in Japan and Bombay in India. Of this population, Metropolitan Lagos, an area covering 37% of the land area of Lagos State is home to over 85% of the state population 15.The University of Lagos - popularly known as Unilag - is a federal government university, founded in 1962 and is made up of two campuses, the main campus at Akoka, Yaba and the College of Medicine in Idi-Araba, Surulere. The main campus is largely surrounded by the scenic view of the Lagos lagoon and is located on 802 acres (3.25 km2) of land in Akoka, North Eastern part of Yaba, Lagos, the Centre of Excellence and aquatic splendour. From a modest intake of 131 students in 1962, enrolment in the university has now grown to over 39,000. It has total staff strength of 3,365 made up of 1,386 Administrative and Technical Staff, 1,164 Junior and 813 Academic Staff. 16 The University is composed of 12 Faculties, three of which are situated in the College of Medicine. The Faculties offer a total of 117 programmes in Arts, Social Sciences, Environmental Sciences, Pharmacy, Law, Engineering, Sciences, Business Administration and Education. UNILAG also offersMaster’s and Doctorate degrees in most of the aforementioned programmes.

2.2. The College of Medicine, University of Lagos (CMUL)

The College of Medicine was conceived by the founding fathers as a Medical School with some degree of autonomy within the University of Lagos. It was founded to produce highly trained medical manpower to provide specialised medical services and to conduct research into health related problems. In October 1962, the first batch of 28 medical students were admitted into the College. 17Over the past 50 years, successive leadership of the College has worked towards the realisation of these lofty goals and the College has grown remarkably, with three faculties: Basic Medical Sciences, Clinical Sciences and Dental Sciences. The College consists of 32 departments with an undergraduate student population of over 1,700 and staff strength of 1,111. 17 To date, the College has produced over 6000 graduates in disciplines of Medicine, Dentistry, Pharmacy, Microbiology, Biochemistry, Physiotherapy, Physiology and Pharmacology. It has also produced graduates with M.Sc, M.Phil, Ph.D and MD degrees in these areas.

2.3. Study design

Study design -was a descriptive cross-sectional study to assess the knowledge, attitude and consumption practices of genetically modified foods amongst undergraduate medical and dental students of the CMUL.Comprised of undergraduate medical and dental students of the CMUL, Lagos, Nigeria. The combine total population of the medical and dental students from 200 to 600 levels for the 2010/2011 session was 1,170 (882 and 288 respectively).

2.5. Sampling

A convenient sample of three hundred and eighteen (318) medical and dental students at 200 - 600 Level MBBS/BDS programmes was done after detailed explanation of the study and its objectives.

2.6. Data Collection Tools and Techniques

Data collection was done using a self–administered questionnaire adapted from previous studies[12, 13,14]. The questionnaire was pre-tested amongst twenty 200-600 level undergraduate medical and dental students of the College of Medicine, Lagos State University, Ikeja and amended as appropriate. Informed consent was obtained from the students after receiving information about the study and its objectives. Information obtained includedsocio-demographic characteristics of respondents, knowledge, attitude and consumption of GM foods.

2.7. Data Management

Data analysis was carried out using EPI-INFO version 6.4 (a statistical software jointly developed by the CDC and WHO) to compute frequencies, percentages, cross-tabulation, test of significance with chi-square and multiple logistic regression, level of significance was set P<0.05. To assess overall knowledge, a score of one point was allotted to each of the ten questions that made up the knowledge section of the questionnaire, except for the question on awareness of GMO/GMF (HEARD II), which was allotted 2 points. The total mark was 11 point and the scale of knowledge was graded in three as: Good (9-11/11), fair (6-8/11) and poor (0-5/11). In applying the scale, those who chose the wrong option or did not know the answer were scored zero (0). (See appendices).Rating overall attitude and perception was not as straight forward. This was partly because many of the questions border on some of the controversial issues vehemently debated by those for or against universal acceptance of GM technology. Unlike Boccaletti & Moro’s Italian study in which respondents were allowed to rate their attitude towards GM foods, a detailed examination of some of the contemporary issues driving GM debate across the world and some of the concerns raised by supporters and antagonists here in Nigeria was carefully carried out and six (6) questions were selected from the list of nine (9) questions in the attitude and perception section of the questionnaire. Such questions include: GM foods have more quality nutrient and better health benefits compared to non-GM, GM foods carry potential health risks and it is ethically acceptable to genetically modify foods amongst others. While “X” was scored zero (0) indicating responses that reflected negative attitude towards GM, “√” was scored one (1) point each in favour of responses that signalled positive disposition towards GM. On a scale of a total score of six (6) points, ≥ 3 was rated as having an overall positive attitude/favourable perception about GM, while score <3 were rated overall negative attitude/unfavourable perception.

2.8. Ethical Consideration

Participation in the study was voluntary; verbal informed consent was sought before questionnaires were administered. Subjects were assured of the confidentiality of the information provided.

2.9. Limitations

A relative dearth of statistics particularly in Sub-Saharan Africa was a limitation in conducting this research; in addition, the unwillingness of some individuals within the study population to participate in the study, as well as the challenge posed by the relatively low level of public awareness of GM foods.

3. Results

3.1. Socio-demographic Characteristics of Respondents

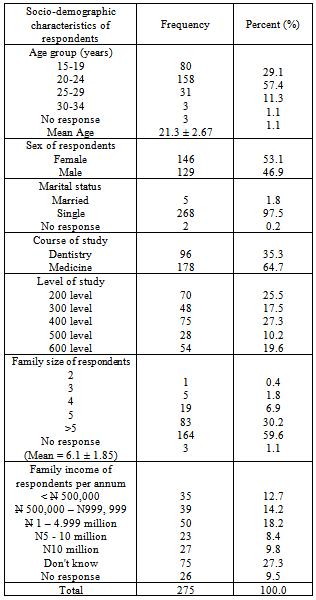

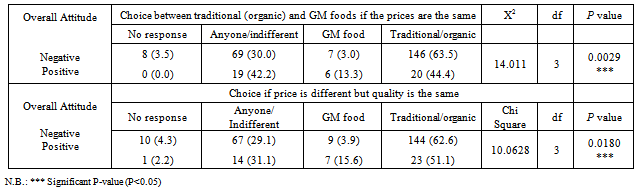

Three hundred and eighteen (318) questionnaires were given out, 275 were returned (yielding a response rate of 86.5%) and were analysed.Approximately less than half (44% and 48.4% respectively) of the students were within the <20 and 20-25 age groups, 6.5% were above 25 years. Mean and standard deviation of age distribution was 21.3 ± 2.67 years. Slightly more than half (53.1%) of the respondents were females while 46.9% were males. Expectedly, majority of the respondents representing 97.5% (268) were single, while 1.8% (5) were married. (Table 1)Table 1. Socio- demographic Characteristics of Respondents

|

| |

|

About two-third (65%) of the total respondents were medical students while the remaining one-third (35%) were dental students. A breakdown of the year of study of respondents showed that about half (52.8%) of them were either in the second and fourth year, while fifth year students accounted for the least proportion of 10.2% (28). Almost 6 out of 10 (59.6%) of the students were from a family size of greater than 5, while those from families of “5” constituted 30.2%. those with family size less than 5 were less than one tenth (9.1%). Three (1.1%) declined to comment on family size. The mean ± standard deviation of family size was 6.1 ± 1.85. (Table 1)On annual family income, results show that slightly more than one third (36.8%) of the students either did not know the state of their family finances or declined response. This is closely followed by 32.4% who indicated that their annual family income was between N500, 000 – N 4.999 million of which 50 (18.2%) indicated N1- N 4.999 million, while 35 indicated less than N 500,000. (Table 1)A little more than a quarter (27.3%) of the respondents were the first borns in their families, while 68.8% of the respondents occupied the 2nd to 13th birth positions amongst their siblings. 4% declined to disclose their birth order.

3.2. Knowledge of Genetically Modified (GM) Organisms/Foods

Table 2. Knowledge of Respondents on GM Foods/Organisms I (N= 275)

|

| |

|

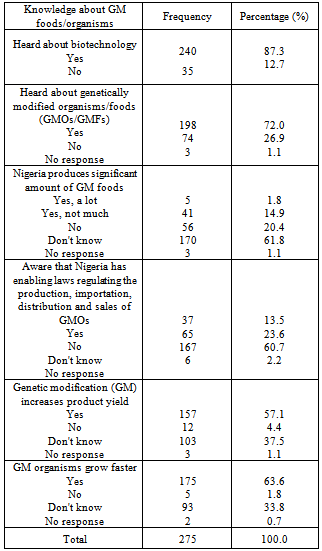

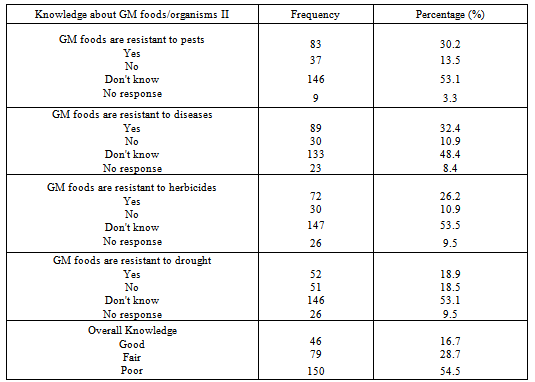

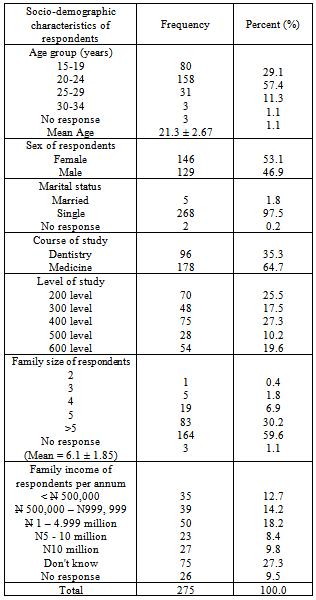

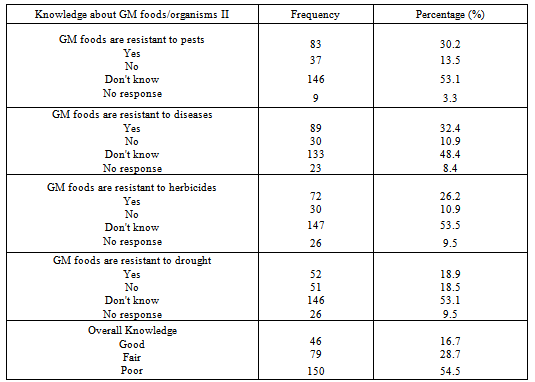

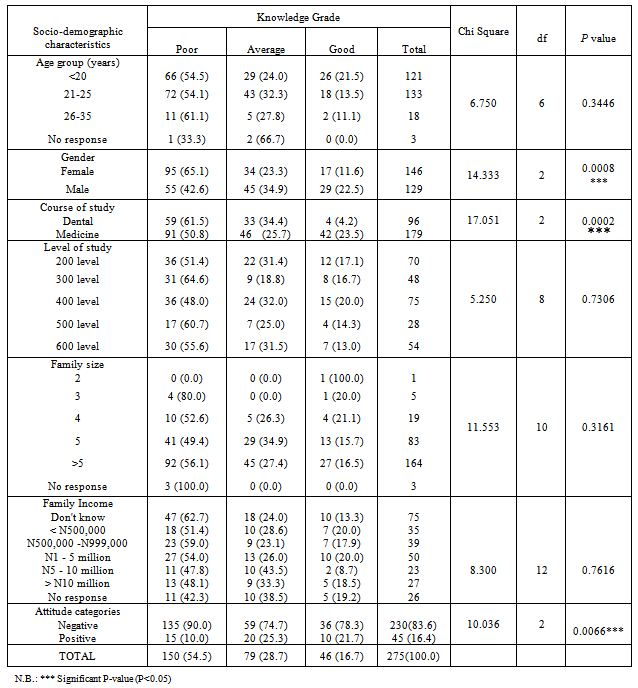

The level of awareness about biotechnology and genetically modified (GM) organisms/foods were quite high: 87.3% and 72% respectively. However, on the more specific properties for which GM plants may be engineered, majority of the students didn’t appear to know much, with 53.5% and 53.1% not knowing if GM products could be resistant to herbicides (pesticides) and drought respectively. However, about a third (32.4% and 30.2%) were aware of resistance to diseases and pests respectively. (Table 3)Majority of the students (61.8%) didn’t know if “Nigeria produces considerable amount of GM products,” 20.4% correctly answered “no” while a tiny minority (1.8%) incorrectly said “yes, a lot.” Also, majority of the respondents (60.7%) didn’t know if Nigeria has laws regulating the production, importation, distribution and sales of GM products, while 13.5% erroneously said “yes,” 23.6% correctly chose “no” and 2.2% did not respond. Approximately half of the respondents (52.4%) did not know if GM products were sold in Nigeria, while 36.7% claimed to be aware. More than half (57.1% and 63.6% respectively) of the respondents were aware of the capability of GM organisms to increase yields and grow faster. (Table 2)To assess overall knowledge, a scale of 11 points, a point grade was used: Good (9-11/11), fair (6-8/11) and poor (0-5/11). In applying the scale, those who chose the wrong option or those who said they did not know were scored zero (0). Using this scale, slightly more than half (54.5%) of the respondents had poor knowledge, 28.7% had fair knowledge, while slightly more than ten percent (16.7%) had good knowledge on GM organisms/foods. (Table 3)

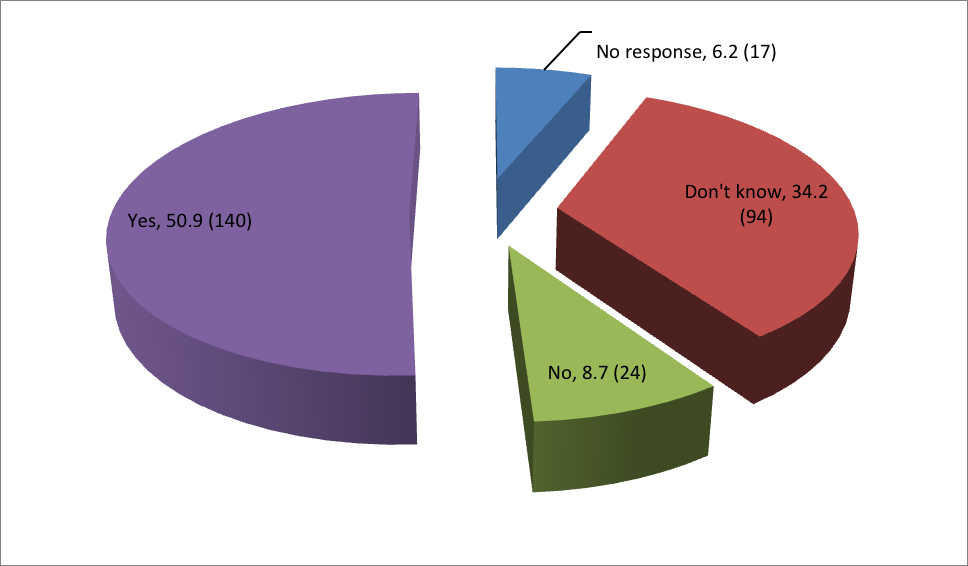

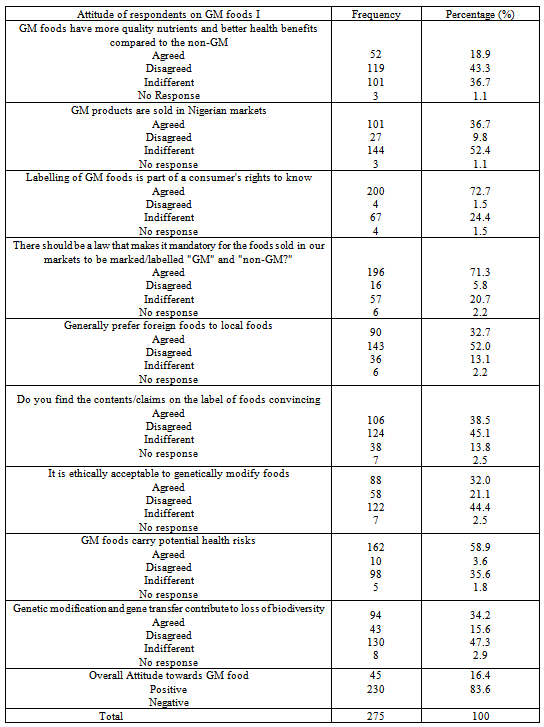

3.3. Attitude to Genetically Modified (GM) Organisms/Foods

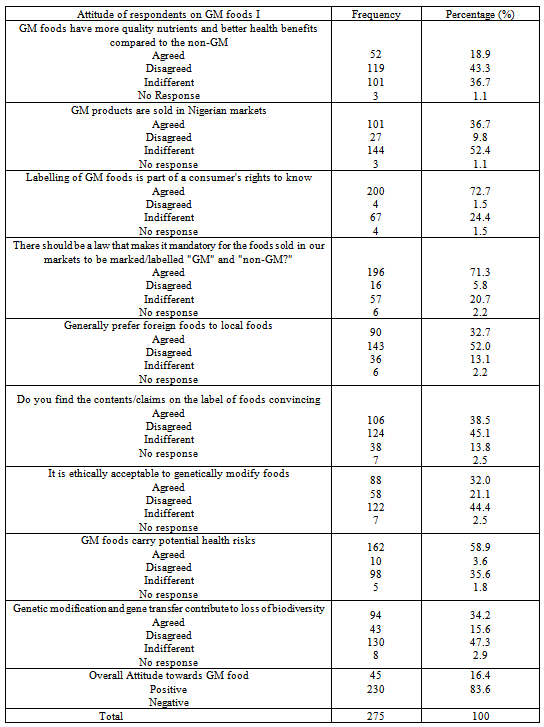

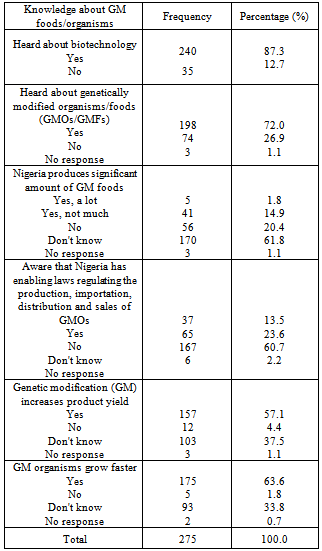

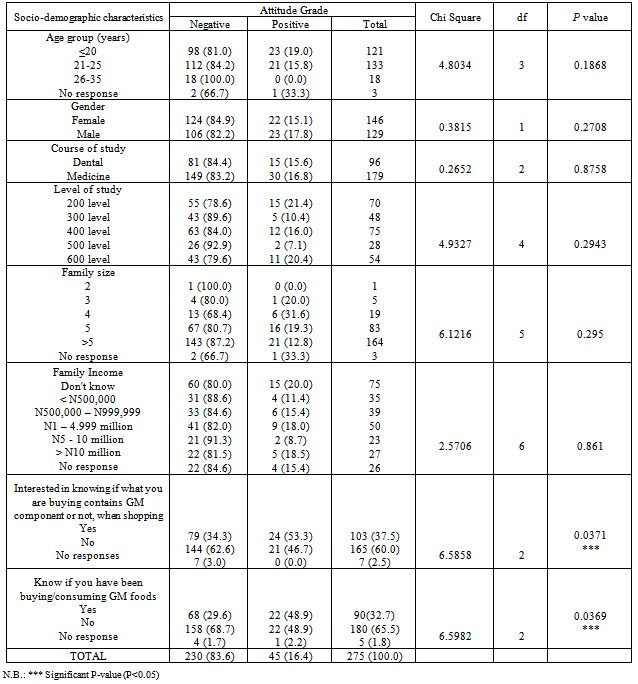

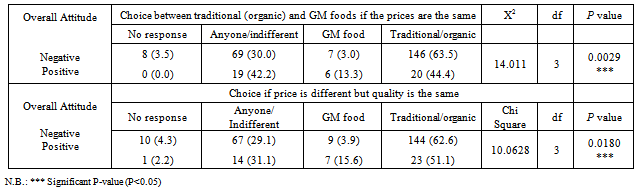

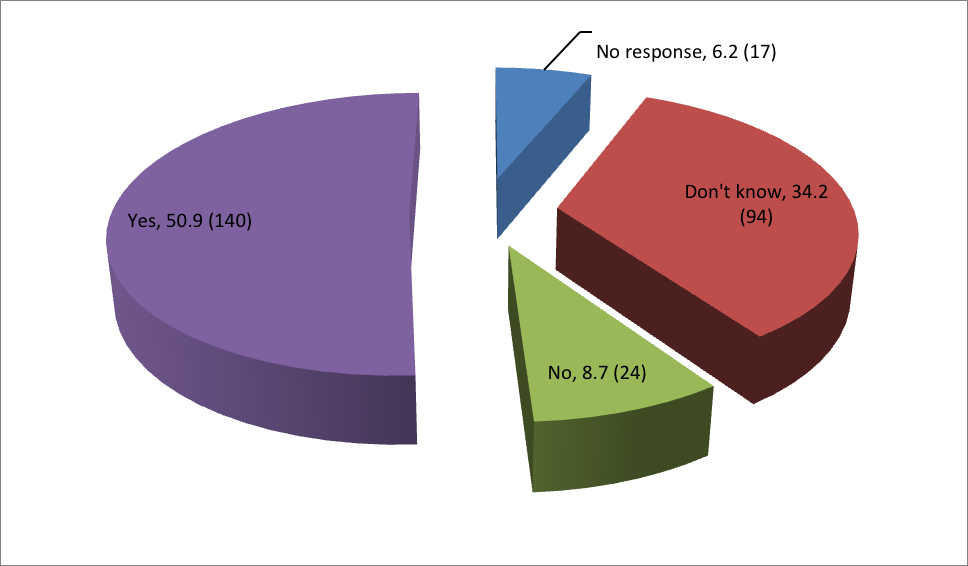

Almost three-quarters (71.3%) of the respondents expressed the need for mandatory labeling of foods in our market as “GM” or “non-GM” and that such labeling was part of consumers’ rights to know (labeling as rights = 72.7%). However, 43.3% did not believe that GM foods have more quality nutrients and better health benefits compared to non-GM foods; 18.9% believed, while 36.7% were not sure. (Table 4)About half (52%) of the respondents reported not to have preferences for foreign foods/products over local ones; 32.7% said “yes,” while 13.1% were indifferent. Slightly more than a third (38.5%) found the contents/claims in the labels of food convincing, while 45.1% did not.On ethics, 21.1% considered genetic modification of organisms for food as ethically unacceptable, 44.4% were not sure and 32.0% found it acceptable. Almost half (47.3%) did not know if genetic modification led to loss of biodiversity, while 34.2% were sure. On the potential health risks of GM, 58.9% of the students believed that there were risks associated with GM products, while 10% disagreed. (Table 4)About half (50.9%) of the respondents agreed that it was profitable to use GM technology to address global food crisis compared to a 34.2% (94) and 8.7% (24) who were either not sure or expressly disagreed respectively (Fig 1). Overall attitude revealed that, majority (83.6%) of the respondents had negative attitude towards GM products, while about one-sixth (16.4%) had positive attitude (were favourably disposed) towards GM products. (Table 4)

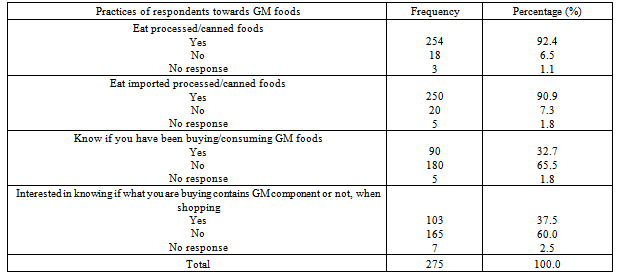

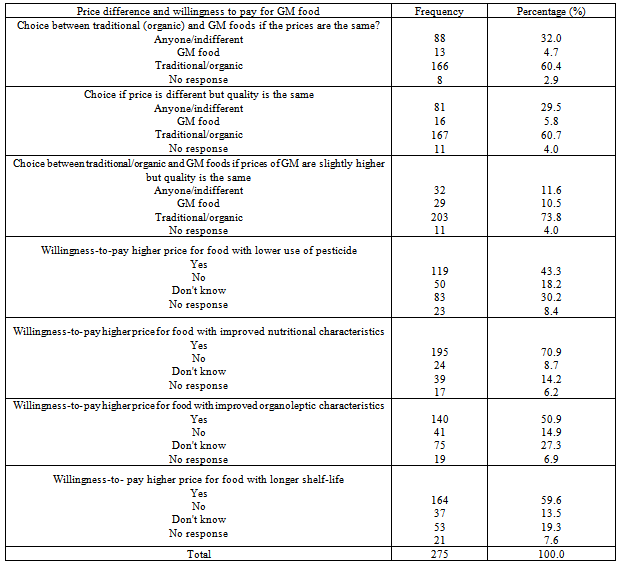

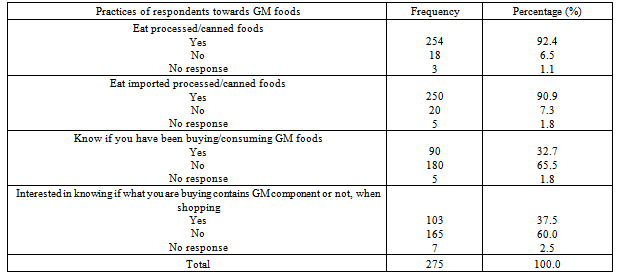

3.4. Consumption Practices Regarding Genetically Modified Organisms /Foods

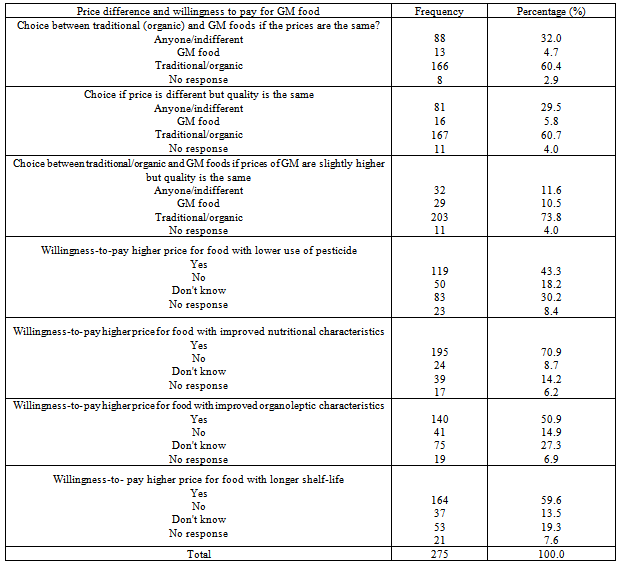

While 92.4% and 90.9% accepted eating processed canned foods and imported processed/canned foods respectively, 65.5% and 60.0% were not aware if they had been buying/consuming GM products or looking out to know if what they were buying contained GM components respectively. (Table 5)When shopping, only 38.4% of respondents would be interested in knowing if what they are buying contain GM components or not. 62.2% of respondents would choose to buy traditional (organic) foods if the prices of traditional and GM foods were the same. Only 4.9% of respondents would choose to buy GM foods if the prices of traditional and GM foods were the same; 33% would buy anyone or indifferent to this question. If the prices are different but quality of traditional and GM foods are the same, 63.3% would prefer to buy traditional/organic foods, 6.1% would prefer GM foods and 30.7% would buy anyone/indifferent. About a quarter (75.6%) of respondents would be willing to buy foods with improved nutritional characteristics, 9.3% would not and 15.1% did not know if they would be willing to buy foods with improved nutritional characteristics. Slightly more than half (54.7%) of respondents would be willing to buy foods with improved organoleptic characteristics, 16% would not and 29.3% did not know if they would be willing to buy foods with such characteristics. Approximately two-thirds (64.6%) of respondents would be willing to buy foods with longer shelf life, 14.6% will not be willing while 20.9% did not know if they would be willing to buy foods with longer shelf life. Almost half (47.2%) of respondents would be willing to buy foods with lower pesticides, 19.8% did not know if they would be willing to buy foods with lower pesticides.

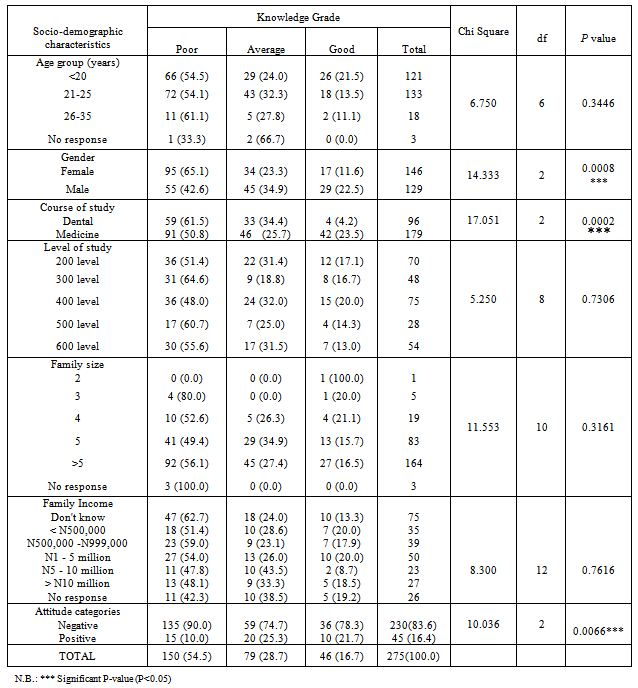

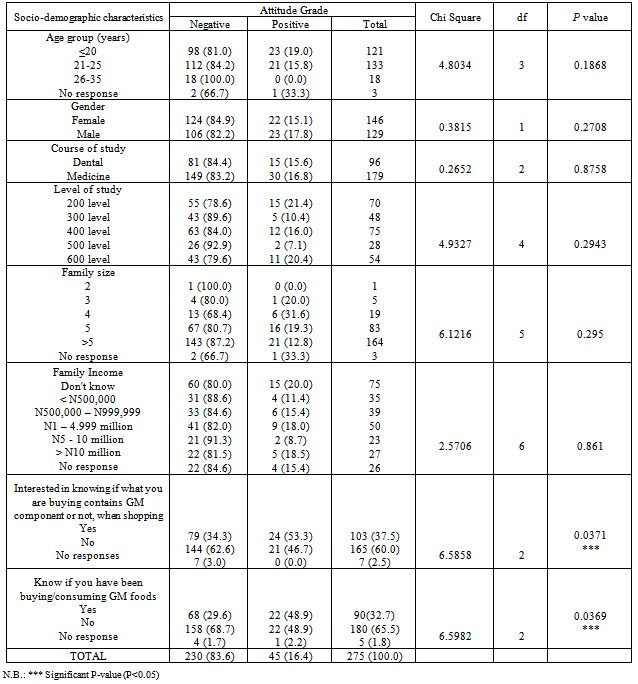

3.5. Association between Socio-demographic Characteristics of the Respondents and Knowledge, Attitude and Practices Regarding Genetically Modified Foods/Organisms

Testing associations between socio-demographic characteristics of respondents and their knowledge, attitude and consumption of GM foods, findings revealed that gender (p=0.0008) and course of study (p=0.0002) were statistically significantly associated with the level of knowledge of GM foods/organisms among the respondents, while other demographic variables (age group (p=0.954), level of study (p= 0.731), family size (p= 0.293) and birth order (p=0.327) were not statistically significantly associated with the level of knowledge (Table 7). About one-tenth (11.6%) of females had good knowledge of GM foods while approximately twice as much (22.5%) of male respondents had good knowledge of GM foods. Slightly less than a quarter (23.6%) of medical students had good knowledge of GM foods while only 4.2% of dental students had good knowledge about GM foods. No significant association was found between annual family income and the level of knowledge (p=0.766). Knowledge was statistically significantly associated with the attitude of respondents toward GMFs/GMOs (P =0.0066). Nine out of ten (90%) of those with poor knowledge had negative attitude, while approximately a quarter (25.3% and 21.7%) of those with average and good knowledge respectively, had positive attitude to GM foods thus explaining the role of knowledge in informing attitude.There was no statistically significant association between socio-demographic variables of respondents and attitude towards GM products, age group (p=0.584), sex (p=0.324), marital status (p=0.412), course of study (p=0.468), level of study (p=0.294), family size (p=0.072), annual family income (p=0.771) and birth order (p=0.076) (Table 8). However, overall knowledge (p=0.042) and overall attitude (p=0.003) were significantly associated with choice between traditional (organic) and GM foods, if the prices of GM are slightly higher and quality is the same. There was no statistically significant association between overall knowledge (p=0.071) and choice between traditional/organic and GM foods if price is different but quality is the same. However, there was a significant association (p=0.009) between overall attitude and choice between traditional/ organic foods and GM foods if price is different but quality is the same. Approximately two-thirds (65.5%) of those with negative attitude towards GM foods will choose traditional foods over GM food under this scenario while only 15.9% of those with positive attitude will choose GM foods over traditional foods under this circumstance. There was no significant association between overall knowledge (p=0.108) and overall attitude (p=0.231) and willingness to buy GM foods with improved nutritional characteristics. There was however a significant association between overall knowledge (p=0.000) and willingness to buy foods with improved organoleptic characteristics as 80% of those with good knowledge about GM foods were willing to buy foods with improved organoleptic characteristics while only 48.6% of those with poor knowledge were willing to buy foods with improved organoleptic characteristics. However overall attitude did not significantly (p=0.120) influence willingness to buy foods with improved organoleptic characteristics. There was a significant association (p=0.009) between overall knowledge and willingness to buy foods with longer shelf –life. Approximately four-fifth (79.5%) of those with good knowledge were willing to buy foods with longer shelf –life, while approximately six out of ten (57.2%) of those with poor knowledge about GM foods were willing to buy foods with longer shelf –life. Overall attitude however did not significantly influence (p=0.102) willingness to buy foods with longer shelf –life. Approximately three quarters (72.7%) of those with positive attitude towards GM foods were willing to buy foods with longer shelf–life while 62.9% of those with negative attitude were willing to buy foods with longer shelf –life. Overall knowledge (p=0.020) and overall attitude (p=0.009) were significantly associated with willingness to buy foods with lower pesticides. 68.2% of those with good knowledge were willing to buy food with lower pesticides while 39.7% of those with poor knowledge were willing to buy foods with lower pesticides. 65% of those with positive attitude were willing to buy foods with lower pesticides while 43.9% of those with negative attitude were willing to buy foods with lower pesticides. There was no statistically significant association (P=0.082) between overall knowledge and respondents’ interest in knowing if what they are buying contain GM components or not. 37.8% of those with good knowledge were interested in knowing if what they were buying contain GM components or not; 33.3% of those with poor knowledge were interested in knowing if what they were buying contain GM components or not. However, overall attitude was significantly associated (p=0.019) with respondents’ interest in knowing if what they are buying contain GM components or not. 53.3% of those with positive overall attitude towards GM foods were interested in knowing if what they are buying contain GM components or not, while 35.4% of those with negative overall attitude were interested in knowing if what they are buying contain GM components or not.Using multi-variate analyses of factors influencing choice between traditional and GM foods, when the quality of both types of food are the same, gender (p=0.008, OR=0.493) of the respondents, knowledge (p=0.026. OR=0.542), and attitude (p=0.029, OR= 2.203) to GM foods were the factors influencing choice between traditional and GM foods.When prices of traditional and GM foods are the same, knowledge (p=0.001, OR=0.486) and attitude (p=0.002, OR=3.119) of the respondents, were significantly associated with choice between traditional and GM foods. When price of GM foods are higher than traditional foods but quality is the same, only knowledge of GM foods was statistically significantly (p=0.033, OR=0.523). Only knowledge of GM foods was statistically significantly associated (p=0.011, OR=0.464) with willingness to pay a higher price for foods with improved nutritional value, only family size of respondents was statistically significant (p=0.004, OR=0.435) associated with willingness to pay a higher price for foods with improved organoleptic characteristics; Willingness to pay a higher price for foods with long shelf life was influenced by the quality of both food groups being the same (p=0.041, OR=1.756) and knowledge (p=0.034, OR=0.557). Similarly, willingness to pay a higher price for foods with lower pesticides was significantly influenced by only knowledge (p=0.037, OR=0.575) and study level (p=0.019, OR= 2.043) of respondents.

4. Discussion

4.1. Respondents’ knowledge on GM Foods/Organisms

Awareness about biotechnology and genetically modified (GM) foods/organisms were quite high, unlike Boccaletti and Moro’s Italian Study of 1999-2000 18, which revealed that 51% had an awareness of GM products. The relatively higher awareness among the respondents of this study might have been due to two major factors: 1) the global evolution and spread of GM technology between the year 2000 and 2011; and 2) the fact that respondents in this study were medical and dental students, and being in formal educational settings, were more likely to have been exposed to teachings in nutrition during their medical and dental training, than the respondents from the general population in the province of Piacenza in Northern Italy.Only one fifth (20.4%) of the students correctly identified that, Nigeria presently does not produce a considerable quantity of GM products, Similarly, more than half of the respondents (60.7%) were unaware if Nigeria had laws regulating the production, importation, distribution and sales of GM products, This shows an obvious gap in respondents’ knowledge concerning national nutrition policies... More than half of the respondents (57.1% and 63.6%) were aware of the capability of GM organisms to increase yields and grow faster respectively. However, on the more specific properties for which GM plants may be engineered, such as resistance to herbicide and drought, most of them lacked awareness about these... In summary, less than half (45.4%) of the respondents had a reasonable level of knowledge about GM foods/organisms. Again, while awareness about GM products was high, knowledge of specific details about GM technology was poor, hence highlighting the need for a more comprehensive and accurate information about GM technology to the general public.

4.2. Respondents’ Attitudes toward GM Foods/Organisms

Almost three-quarters (71.3%) of the respondents expressed the need for mandatory labeling of foods in our markets as “GM” or “non-GM” and that such labeling was part of consumers’ rights to know. This corroborates the Boccaletti and Moro’s 18finding in which 94% of the respondents asked for specific labeling in order to recognize GM foods. However, slightly more than two-fifth (43.3%) did NOT believe that GM foods have more quality nutrients and better health benefits compared to non-GM thus showing their skeptism for GM foodsAbout half (52.4%) did not know if GM products were sold in Nigeria, while 36.7% claimed they knew. Abubakar’s study 14 reported that 75% of respondents did not believe that such products were available, while Boccaletti and Moro’s 18 findings stated that 51.5% of the Italian respondents knew that GM food products were already present in Italian markets. The relatively greater awareness of the Italian respondents compared to the respondents in this study might have been as a result of better access to information on GM-related issues within the Italian society. Compared with Abubakar’s 14 survey, one would expect that medical/dental students to be more informed about issues relating to biotechnology and nutrition than the average member of the public who participated in that survey.About half (52%) of the respondents claimed not to have preferences for foreign foods/products over local ones. Since, GM foods are mostly grown outside Nigeria, it thus imply that those who prefer foreign foods, may be more exposed to consuming GM foods than their counterparts that prefer local/traditional meals. Slightly above one third (38.5%) found the contents/ claims in the labels of food convincing, while 45.1% did not. This may suggest consumers’ “lack of faith” in the information on the labels considering that almost three quarters (71.3%) stressed the need for mandatory labelling of foods in the market, hence manufacturers need to do more to win consumers ‘confidence in accepting that products’ labels convey accurate information regarding the content of such products. On ethics, about one fifth (21.1%) considered genetic modification of organisms for food as ethically unacceptable, 44.4% were not sure and 32.0% found it acceptable. This corroborated Abubakar’s findings 14 that 22% of Nigerians believed that creating hybrid plants through genetic modification was morally wrong, and that 70% of Nigerians did not view such practices as being immoral 14.Furthermore, almost half (47.3%) of the respondents did not know if genetic modification led to loss of biodiversity, while 34.2% were sure. On the potential health risks of GMO, 58.9% of the students agreed that there were risks associated with GM products, thus expressing concerns about safety of GM products.Based on the above, only about one-sixth (16.4%) had a positive attitude or were favourably disposed toward GM products. This sharply contrast the findings reported by Oladele & Subair 12 who reported that approximately twice as much (33.3%) of their respondents were positively disposed to GM foods, while Alarima’s study 13 showed that 53% had a positive perception and attitude. This obvious difference could be explained in two ways: 1) it must be noted that in both reported surveys, the rating scale allowed for “indifference” in the overall score on attitude, whereas this study rated overall attitude as either positive or negative; 2) the respondents in the stated studies were scientists who were better informed about the risks and benefits of GMOs, unlike this study that involved students, many of whom probably heard about GMOs recently.In the Italian survey, which involved a heterogeneous population, Boccalletti & Moro 18 reported that 46% of the respondents rated their attitude toward GM foods as positive, while 27.5% were negative. When compared with the Italian survey in which respondents directly opined whether they had an overall positive or negative attitude to GM foods, this study used an indirect scoring system to assess respondents’ overall attitude, based on their responses to multiple questions on attitude.

4.3. Consumption Practices towards GM Foods and Preferences

While 92.4% and 90.9% accepted eating locally processed canned foods and imported processed/canned foods respectively, 65.5% and 60.0% were not aware if they had been buying/consuming GM products or looking out to know if what they were buying contained GM components respectively, but 32.7% admitted that they had bought/eaten GM products as against 10% and 24% reported by Abubakar 14 and Boccaletti & Moro 18 respectively.The respondents showed preferences for traditional / organic foods over GM foods in each of the three assessed scenarios of GM product/price differentiations respectively: if prices were the same (60.4%); different prices, same quality (60.7%); and price of GM was higher but quality remained the same (73.8%). Likewise, the proportion of those with preferences for GM increases as the need to pay more for it increases: from 4.7% when prices were the same to 10.5% when a premium was to be charged on GM. In the same vein, the choice of those who were indifferent when prices were the same or not specified, reduced as the question turned towards increased price in favour of GM, suggesting that price has a role to play in influencing choices.On willingness-to-pay a higher price for foods, 70.9% and 59.6% of respondents were willing to pay a higher price for foods with improved nutritional characteristics and longer shelf life respectively, while 50.9% and 43.3% of the respondents were willing-to-pay a higher price for foods with improved organoleptic (relating to odour, shape and taste) properties and lower pesticide use respectively. Thus showing respondents’ willingness to pay more for products with improved nutritional characteristics.Almost half (50.9%, 140) of the respondents agreed that it was profitable to use GM technology to solve global food crisis compared to 34.2% (94) and 8.7% (24) who were either not sure or disagreed respectively. This is very important in the light of the current state of global hunger and malnutrition, and when compared with positive responses from questions on GM yields (54.3%); faster growth (64.1%); improved nutritional characteristics (75.6%). However, care must be taken to take into account the view expressed by those who thought GM foods carry potentially deleterious health consequences (58.9%) and that genetic modification leads to loss of biodiversity (34.2%).

4.4. Factors Influencing Knowledge, Attitude and Consumption Practices Regarding GM Foods

Among the socio-demographic characteristics of respondents, only sex and course of study were found to show statistically significant associations with the level of knowledge of GM foods/organisms among the respondents (P = 0.0008 and 0.0002 respectively). Out of the 146 female respondents, only 17 (11.6%) had overall good knowledge of GM as against 42 out of 129 males (22.5%) who had good knowledge (Table 7).Similarly, only 4 (4.2%) of the dental students had overall good knowledge of GM foods as against 42 (23.5%) medical students. This difference in knowledge levels was statistically significant (p = 0.0002), and could be due to the fact that the medical curriculum has a relatively wider content, inclusive of nutrition, in comparison to the relatively narrower dental curriculum. Ninety percent of those with overall poor knowledge about GM foods had overall negative attitude, while 66.7% of those with positive attitude toward GM foods had either average or good knowledge. Therefore, at P=0.007, there is significant association between attitude and knowledge, implying that their attitude was influenced by their knowledge about GM products. This therefore, confirms the finding by Alarima13 that respondents’ perception was among other things, related to knowledge. However, there was no statistically significant association between any of the socio-demographic variables and overall attitude since P values were greater than 0.05.The result also shows that overall attitude influenced their consumption practices of GM foods as well as awareness of purchasing foods that were genetically modified or not at P = 0.037) (Table 8): only 34.3% of those with overall negative attitude were interested in knowing if what they buy contained GM components or not when shopping as against 53.3% of those with overall positive attitude. Furthermore, 48.9% of respondents with overall positive attitude were aware of buying or consuming GM foods, while majority (68.7%) of those with overall negative attitude said they were not interested in knowing if what they bought consumed was genetically modified. This implies that attitude has a role to play in the level of acceptance/ consumption of genetically modified food. Finally, the relationship between attitude of respondents to GM foods and their preferences showing different pricing scenarios. The results showed that respondents’ overall attitude influenced their preferences for traditional foods over GM foods (P = 0.003 and 0.018 respectively) (Table 9). In the first scenario, if prices of GM foods and traditional/ organic foods were the same, 3.0% and 63.5% of those with overall negative attitude went for GM foods and traditional/ organic foods respectively, while 13.3% and 44.4% of those with overall positive attitude settled for GM and traditional foods respectively.In the second scenario, the prices are different but quality is the same: 29.1%, 3.9% and 62.6% of those with overall negative attitude went for anyone/indifferent, GM foods and traditional/organic respectively as against 31.1%, 15.6% and 51.1% respectively of those with overall positive knowledge. Although the differences here are relatively marginal, it shows more preference for traditional/organic foods.However, using multi-variate analyses of factors influencing choice between traditional and GM foods, when the quality of both types of food are the same, gender (p=0.008, OR=0.49) of the respondents, knowledge (p=0.0264. OR=0.542), and attitude (p=0.0292, OR= 2.203) to GM foods were the factors influencing choice between traditional and GM foods.When price of traditional and GM foods are the same, knowledge (p=0.0095, OR=0.486) and attitude (p=0.0018, OR=3.119) of the respondents, were significantly associated with choice between traditional and GM foods. When price of GM foods are higher than traditional foods but quality is the same, only knowledge of GM foods was statistically significantly (p=0.033, OR=0.523). On willingness to higher price for foods with improved nutritional value, only knowledge of GM foods was statistically significantly associated (p=0.0108, OR=0.464) with willingness to pay higher price. Willingness to pay higher price for foods with improved organoleptic characteristics; only family size of respondents was statistically significant (p=0.0036, OR= 0.435) with willingness. Willingness to pay higher price for foods with long shelf life was influenced by choice, if the qualities of both food groups are the same (p=0.0407, OR=1.756), knowledge (p=0.0337, OR=0.557). Knowledge (p=0.0372, OR=0.575) and study level (p=0.0187, OR= 2.043) of respondents were statistically significantly associated with willingness to pay higher price for foods with lower pesticides.From this analysis, knowledge and attitude towards GM foods were the most consistent variables influencing choices between traditional and GM foods amongst the respondents.

5. Conclusions

The study revealed that although majority of the respondents had awareness about biotechnology and genetically modified foods/organisms, however knowledge about the specifics of GM foods and technology were generally poor. Expectedly, their poor knowledge about GMOs influenced their perceptions that underscored negative attitudes, which in turn influenced their consumption and preferences for traditional/organic foods over genetically modified products.Specifically, gender and course of study had statistically significant association with the knowledge of therespondents, whereas other socio-demographic variables did not.With respect to consumption and preferences, higher price for GM products as well as attitude appeared to be the predictors for majority of the respondents’ preferences for traditional/organic foods. Therefore, as governments at all levels and large scale farmers attempt to use measures to harness the mass production of GM products in Nigeria, there is the need to consider safety issues and proper pricing regime that will ensure relative price parity between GMOs and organic foods.

6. Recommendations

As earlier stated in this study, more and more countries are adopting genetically modified (GM) foods, despite the concerns expressed by some scientists and environmental activists about the potential dangers to man and the ecosystem. Given the potential economic, social and environmental impacts of GM foods and technology, it is quite obvious that a small survey such as this, while important, is not enough. Continuous research is imperative to help consumers, farmers, industrialists and policy makers to evaluate the role of genetic modification in the future marketplace.There is also the need for better public enlightenment campaign on the benefits and risks of GMOs, to minimize negative perceptions. Also, given the fact that most respondents sought a legalization of appropriate labeling of foods as “GMOs” or “non-GMOs,” it is important that this, among other things, be incorporated into any future legislation that would regulate GMOs in Nigeria.Finally, seeking to have a biosafety law that will regulate GMOs and other issues related thereto is not enough. Rather, the government in collaboration with research and academic institutions undertake a 3-phase nation wide survey: first to ascertain Nigerians’ perceptions; then enlighten them about GMOs and GM technology, and carry out a final survey to see if there are changes in knowledge, attitude and perceptions about GMO, post enlightenment. Such findings, if incorporated into the proposed biosafety law, would go a long way in making the technology acceptable to most Nigerians.

6.1. Knowledge of Respondents

| Figure 1. GM technology can profitably fight global food crisis in Nigeria and the world over (n = 275) |

Table 3. Knowledge of respondents on GM Foods/Organisms II (N = 275)

|

| |

|

6.2. Attitudes of Respondents towards GM Foods/Organisms

Table 4. Attitude and perception of respondents on GM I (N = 275)

|

| |

|

6.3. Consumption and Willingness-to-Buy

Table 5. Patterns of Consumption of GM Foods by Respondents (n = 275)

|

| |

|

Table 6. Price Difference and Willingness-to-Pay for GM food (N = 275)

|

| |

|

6.4. Measures of Association – Factors Influecing Knowledge, Attitude and Consumption

Table 7. Association between socio-demographic characteristics of respondents and knowledge of GM foods/organisms (N = 275)

|

| |

|

Table 8. Association between socio-demographic characteristics of respondents and attitude to GM products

|

| |

|

Table 9. Association between respondents’ attitude and preference for GM foods (N = 275)

|

| |

|

References

| [1] | Smithson S. “Eat, Drink, and Be Wary: Genetically modified animals could make it to your plate with minimal testing—and no public input”. Grist Magazine, July 30, 2003. Available from: http://www.grist.org/article/and3 (accessed 12th June, 2011). |

| [2] | Union of Concerned Scientists. “Genetically Engineered Foods Allowed on the Market” February 16, 2006 (accessed 3rd June, 2011).. |

| [3] | California Department of Food and Agriculture. A Food Foresight Analysis of Agricultural Biotechnology: A Report to the Legislature. January 1, 2003. |

| [4] | Benbrook, Charles M. “Impacts of Genetically Engineered Crops on Pesticide Use in the United States: The First Eight Years,” BioTech InfoNet, 2003. |

| [5] | Windley S. Genetically modified foods. Fort Wayne, USA. Pure Health Corporation, Copyright 2008. Available from: www.PureHealthMD.com, accessed 2nd March, 2011. |

| [6] | Hyde J. Genetically Modified Food: Spreading fear of the future can be good for anti-business. IPA REVIEW ARTICLE, 1999. Available from:http://www.ipa.org |

| [7] | .au/library/.svn/text-base/review51-2%20Genetically%20Modified%20Food.pdf.svn-base, accessed 2nd March, 2011. |

| [8] | Hyde J. Regulating Biotechnology: Some Questions and Answers. IPA Backgrounder, May, 2000. |

| [9] | Greenwell P, Rughooputh S. Genetically modified food: good news but bad press. The Biomedical Scientist, August 2004; 48(8): 845-846. |

| [10] | Kalaitzandonakes N (ed). The economic and environmental impacts of Agbiotech: a global perspective. New York: Springer; 2003. |

| [11] | Jefferson-Moore KY, Traxler G. Second-generation GMOs: Where to from here? AgBioforum 2005; 8:143-50. |

| [12] | Qaim M. The economics of Genetically Modified Crops. Annu. Rev. Resour. Econ. 2009; 1:665-95. Available from: http://www.annualreviews.org/doi/pdf/10.1146/annurev.resource.050708.144203, accessed 20th March, 2011. |

| [13] | Oladele OI and Subair SK. Perception of University Lecturers towards Consumption of Genetically Modified Foods in Nigeria and Botswana. A.C.S. 2009; 74 (1): 55-59. |

| [14] | Alarima CI. Knowledge and Perception of Genetically Modified Foods among Agricultural Scientists in South-West Nigeria. OIDA Int’l J. of Sustainable Dev. 2011; 2(1): 77-88. |

| [15] | Abubakar AA. Study on awareness of genetically modified food (biotechnology) among higher socio-economic and educated group (men and women) within the three major tribes (Igbo, Hausa and Yoruba) in Nigeria. National Office for Technology Acquisition and Promotion (NOTAP), Abuja, 2009. Available from: http://www.geotunis.org/2009/file/ ppt/Dr%20Abubakar.ppt). Retrieved on 23rd May, 2011. |

| [16] | Lagos State Government. Information for Visitors. Available from:http://www.lagosstate.gov.ng/index.php?page=subpage&spid=9&mnu=null. Accessed on 20th May, 2011. |

| [17] | University of Lagos. History of the University of Lagos. Available from: www.unilag.edu.ng, accessed on 20th May, 2011. |

| [18] | College of Medicine, University of Lagos (CMUL). Welcome Note from the Provost. Available from: www.cmul.edu.ng, accessed on 1st June, 2011. |

| [19] | Boccaletti S, Moro D. Consumer willingness-to-pay for GM food products in Italy. AgBioForum 2000; 3(4): 259-267. |

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML