-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Food and Public Health

p-ISSN: 2162-9412 e-ISSN: 2162-8440

2012; 2(6): 202-212

doi: 10.5923/j.fph.20120206.04

Comparative Examination of Trust During Times of a Food Scandal in Europe and Australia

John Coveney 1, Loreen Mamerow 1, Anne Taylor 2, Julie Henderson 3, Samantha Myer 1, Paul Ward 1

1Discipline of Public Health, Flinders University, Adelaide, 5001, Australia

2Population Research & Outcome Studies (PROS), Discipline of Medicine, University of Adelaide, 5000, Australia

3School of Nursing and Midwifery, Flinders University, Adelaide, 5001, Australia

Correspondence to: John Coveney , Discipline of Public Health, Flinders University, Adelaide, 5001, Australia.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This study compared public confidence in truth-telling by food chain actors in selected EU countries, where there have been a number of food safety problems, with consumers in Australia, where there have been fewer food crises.A computer assisted telephone interviewing survey was used addressing aspect of truth-telling at times of a food scandal was administrated to a random sample of 1109 participants across all Australian states (response rate 41.2%). Results were compared with a survey in six EU countries which had asked similar questions. Australians' trust in truth-telling by food chain actors was low, with 14.2% of the sample expecting various institutions and individuals to tell the whole truth during times of a food scandal. When compared with EU countries, Australia occupied a middle position in trust distribution, and was more similar to Great Britain in giving farmers the most trust in truth-telling. This study has demonstrated that in Australia, as in many EU countries, trust in truth-telling at a time of food scandal is low. The credibility of the food system is highly vulnerable under times of food crisis and once trust in broken, it is difficult to restore.

Keywords: Strust, Food Scare, Survey, Australia

Cite this paper: John Coveney , Loreen Mamerow , Anne Taylor , Julie Henderson , Samantha Myer , Paul Ward , "Comparative Examination of Trust During Times of a Food Scandal in Europe and Australia", Food and Public Health, Vol. 2 No. 6, 2012, pp. 202-212. doi: 10.5923/j.fph.20120206.04.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Having endured a number of scares and scandals associated with the food quality in Europe, the most recent food scare involving bean sprouts from Germany - which killed 29 people – demonstrated to consumers that there are many vulnerabilities in their food supply[1]. Over the past 20 years jurisdictions in Europe have experienced many such food safety problems. This has included concerns in the 1980s about the use of growth-promoting hormones in beef production, dioxins found in soft drink and listeria outbreaks in France in 1999 and 2000[2], and foot and mouth disease starting in the UK[3]. The most famous of these was the bovine spongiform encephalitis (BSE or ‘mad cow disease’) outbreak starting in the UK in 1986, and later spreading to other parts of Europe[4].Australia, by contrast, has experienced fewer cases of the same magnitude. Those that have occurred on a widespread scale include foods such as fermented sausage or metwurst[5] and orange juice[6]. This is not to suggest that Australian consumers do not experience doubt or suspicion about the safety of the food supply, however. A recent survey of 1200 Australian adults showed that the public are concerned about pesticides, food additives and preservatives in their food[7].Lupton[8] also found metropolitan and regional Australians to be critical of processed foods which were regarded to harbour undesirable chemicals or additives.Food quality problems can impact on overall trust in the food supply, thereby taking a toll on the public’s faith in the systems designed to keep food safe[6]. Trust has been defined as the optimistic acceptance of a vulnerable situation which is based on positive expectations of the intentions of the trusted individual or institution[9].In other words, we put trust in others who we assume will do the right thing by us. This form of trust is implicit in everyday life, especially when responsibility for health and safety have been given over to others, such is the case with the health and safety of the food supply. Given the increasing distance between food producers and food consumers, the investment of trust in the food chain is axiomatic, although problematic because, as pointed out earlier,consumers have been exposed to a number of food scares and scandals. Consumer trust is seen to be important for three reasons: firstly, trust directly affects food choice, and thus nutritional status. Secondly, trust is crucial if consumers are to recognise the benefits of new food technologies, take up expert advice about healthier eating habits, and feel assured that food regulation is protecting their best interests. Finally, trust supports public endorsement of food regulatory and legislative regimes. In brief, without public trust in the integrity of the food supply, consumers are vulnerable to poor dietary choices, misinformation and a lack of faith in the protective regulatory mechanisms. The levels of trust in the food supply and in the governance of the food supply have been dramatically affected in Europe. In the UK for example, public trust in the governance of the food supply has been found to be low[10]. In the EU trust in food regulation and legislation has been found in many countries to be in need of improvement[11]. Of importance is the degree of ‘truth-telling ‘during times when a food scare is being experienced. On these occasions all players along the food chain, from production to retail, come under scrutiny. Also under scrutiny are the governing bodies who are entrusted to keep food safe, and, importantly, the media which conveys relevant information to the public information. These various agencies and bodies have been termed ‘food chain actors’[12].The purpose of the present study was to examine consumer trust in ‘truth telling’ by food chain actors in Australia and in the EU. In particular, the study examined the extent of trust in ‘truth telling’ by actors during times of food scare.A comparison between Australia and the EU jurisdictions included in this study could reveal interesting differences in the ways in which food scares have been managed, and the effects on public perceptions of certain players in the food supply. This is particular pertinent given the different degrees to which consumers in the EU and in Australia have been directly exposed to food safety problems.

2. Method

- The data on which the current investigation is based were collected independently in the European setting in 2002 and in Australia in 2009. Methodological procedures for the European ‘Trust in Food Survey’ including generation and validation of the questionnaire, sampling, as well as data collection, have been described previously[13,14] . The data variables were recoded and the descriptive categories were re-run for the purpose of this study. The Australian data was collected as part of the ‘Trust in Food’ project, funded through the Australian Research Council (ARC). This study was primarily concerned with identifying the nature and level of consumer trust in the Australian food supply. A national survey examined the key theoretical claims about the relationship between food and trust, as well as factors that influenced food trust in different Australian socio-economic population groups.

2.1. Sampling Procedures for Data Collection in Australia

- Households in Australia with a telephone connected and the telephone number listed in the Australian Electronic White Pages (EWP) were eligible for random selection in the sample for this study.All selected households were sent an approach letter on XXXXXXX Universityletterhead, and this detailed the purpose of the study and advised that the household would be receiving a phone call for an interview.The purpose and benefits of the research, the format of the survey, and how more information could be obtained was described in an information sheet accompanying this letter.In order to test question formats and sequence, and to assess survey procedures, a pilot study of n=52 randomly selected households was conducted prior to the main survey.Information obtained from the pilot was used to improve the questionnaire.The person, aged 18 years or over, who was last to have a birthday, was randomly selected within each contacted household to complete the survey.Professional interviewers from a contracted agency conducted the study using Computer Assisted Telephone Interview (CATI) methodology from October to December 2009.This methodology allows immediate entry of data from the interviewer’s questionnaire screen to the computer database.A minimum of 10 call-backs were made to telephone numbers selected, to interview household members and different times of the day or evening were scheduled for each call-back. Non-contactable or responding persons were not replaced with other respondents.Interviews could be rescheduled to a time suitable for the respondent if they were not available to be interviewed straight away.Each interview took an average of 14.5 minutes to complete, and ten percent of each interviewer’s work was validated by the interviewer’s supervisor for quality purposes.Of the initial sample of 4,100, a sample loss of 1,408 occurred due to non-connected numbers (1,060), non-residential numbers (135), ineligible households (139), and fax/modem connections (74), leaving 2692 phone numbers eligible for survey phone calls. After refusals, terminated interviews, non-contactable households, deaths, unavailable respondents and respondents who could not speak English, 1109 interviews were completed. This generated an overall sample response rate of 41.2%.As samples such as these may be disproportionate with respect to the population of interest, weighting was used to compensate for differential non-response and correct unequal sample inclusion probabilities.In order to reflect the Australian population structure 18 years and over, the data were weighted by age and sex reflecting the Australian Bureau of Statistics 2007 Estimated Residential Population.

2.2. Survey Items Utilized for the Current Study

- Of relevance to the present investigation were survey items which specifically addressed the perceived truth-telling practices of different individuals and institutions. Between the Australian and European survey, four items were shared that were utilized for the present examination, which were farmers, politicians, the media as well as supermarket chains1. For the European survey, all items were framed as follows: ‘Imagining that there is a food scandal concerning chicken production in [COUNTRY]. Do you think that the following persons or institutions[media, supermarket chains, farmers, politicians] would tell you the whole truth, part of the truth, or would hold information back?’ In Australia, respondents were asked as slightly shorter version of the same question: ‘Imagining there is a food scandal concerning chicken production in Australia. Do you think the following[media, supermarket chains, farmers, politicians] would tell the truth?’ In both formats, three discrete response options were offered to survey participants, including ‘Whole truth’, ‘Parts of the truth’ and ‘Hold information back’ in Europe and ‘Whole truth’, ‘Parts of the truth’ and ‘Not tell the truth at all’ in Australia. European as well as Australian respondents were furthermore offered less distinct response categories such as ‘Don’t know’ or the option to withhold an answer to a particular question.

2.3. Data Analyses

- All statistical analyses were carried out using the statistical software package SPSS version 17.0. For analytical as well as comparative purposes, the Australian survey items addressing trust in selected individuals’ and institutions’ truth-telling during a food scandal were dichotomised. As this investigation was focused on ascertaining country-specific as well as individual differences in regards to trusting people and institutions to tell the ‘Whole truth’, statements which indicated that people and institutions were believed to tell the ‘Whole truth’ generated one level of the outcome variable, while responses in the form of ‘Not tell the truth at all’ (Australian survey) or ‘Hold information back’ (European survey) as well as ‘Parts of the truth’ were combined to yield the second level (‘Not tell the whole truth’). ‘Don’t know’ statements and refusals to answer a particular question were excluded from the present analysis. Both data sets (i.e. European and Australian) contained weights that were attached to individual cases in order to ensure that no undue influence was exerted on response frequencies by means of a biased sample composition.

3. Results

|

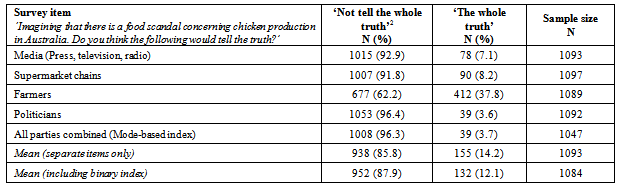

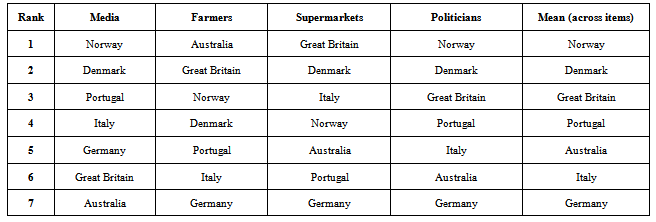

| Figure 1. Australian respondents’ perceptions of the truth-telling practices of selected individuals and institutions during times of a food scandal |

3.1. Truth-telling in Times of a Food Scandal: Australian Survey Results

- Response rates and patterns for the four items assessing Australian survey participants’ trust in being told the truth by various individuals and institutions during a food scandal are summarized in table 1. Generating binary outcome variables while excluding less concrete responses did not markedly affect the number of responses retained for analysis and response rates were relatively similar for all four survey items, ranging from 98.2% (n=1089) to 98.9% (n=1097). The general picture emerging from individuals’ responses is fairly homogenous (figure 1), with all institutions and individuals perceived to ‘Not tell the whole truth’ more frequently than telling the ‘Whole truth’, yielding mean percentages of 85.8% (n=938) and 14.2% (n=155), respectively. These findings were mirrored by response distributions found for a binary index based on the mode of individuals’ responses to the separate survey items, which describes respondents’ general perceptionstowards individuals and institutions and how much of the truth these would disclose during critical times. Generating an index based on mode in addition to mean frequencies was thought to more appropriately reflect individuals’ response patterns, as only responses which showed a clear preference for either response option were retained for analysis. As a result, 94.4% of responses were retained, which emphasizes the fact that most respondents were very clear in their responses across survey items and selected one response option more frequently than the other (96.3% selected ‘Not tell the whole truth’ more often versus 3.7% who stated ‘Whole truth’ more frequently).Looking at the response patterns for each survey item, there was only a slight difference between trust in the media and supermarket chains, with both institutions being perceived to ‘Not tell the whole truth’ more often than telling the ‘Whole truth’: 92.9% of respondents said they believed the media would ‘Not tell the whole truth’, while the same statement was made for supermarket chains by 91.8% of respondents. A more substantial gap was observed for trust placed in the truth-telling of individuals, for 96.4% stated that politicians would ‘Not tell the whole truth’ versus 62.2% replying that farmers would ‘Not tell the whole truth’. Out of all institutions and individuals addressed via the survey questions, farmers were trusted to tell the ‘Whole truth’ more often than any other individual or institution, while politicians were trusted the least often to tell the ‘Whole truth’ (37.8% versus 3.6%, respectively). The general picture which emerges from responses to the survey items under investigation can therefore be summarized as follows: Australians’ trust in the truth-telling practices of all individuals and institutions in question was far from absolute and can at best be described as sceptical or apprehensive. Moreover, due to the survey items being framed in regards to an imagined rather than actual situation, the response frequencies observed are indicative of people having rather low expectations regarding just how much of the truth they would be told during an actual food scandal.

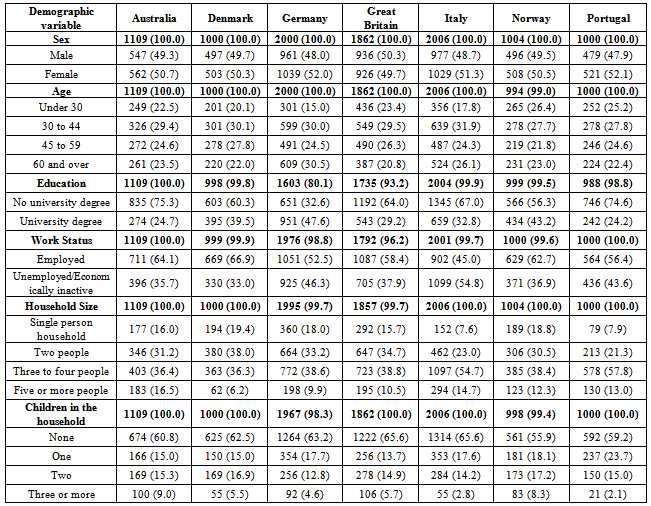

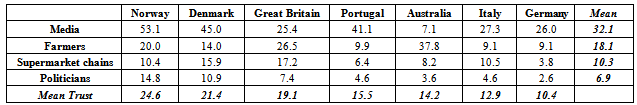

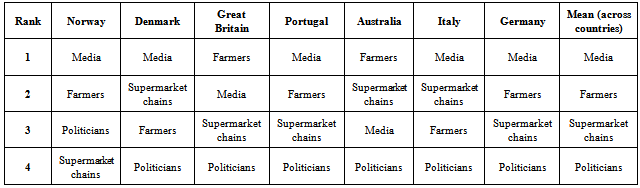

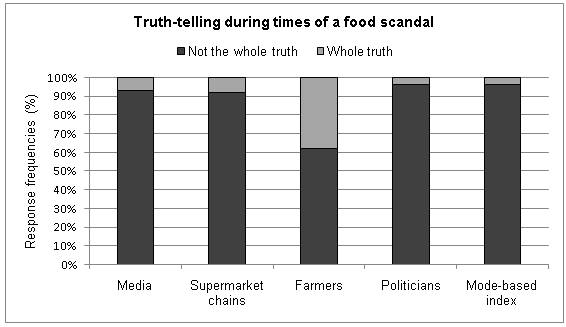

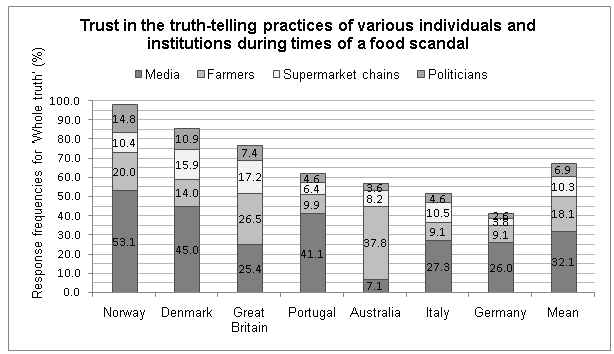

3.2. Truth-telling in Context: Australian Versus European Response Patterns

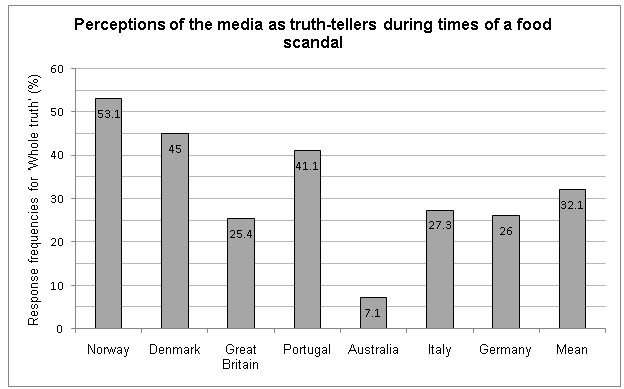

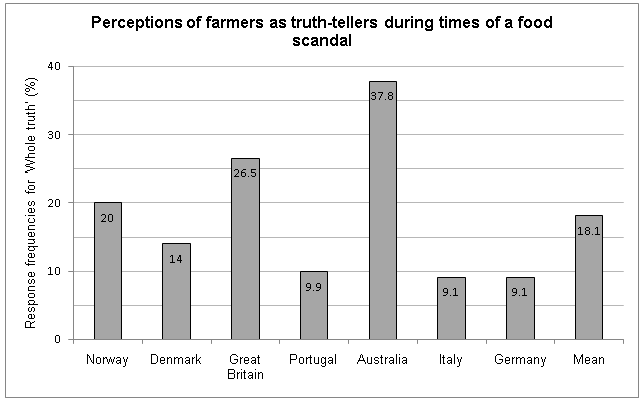

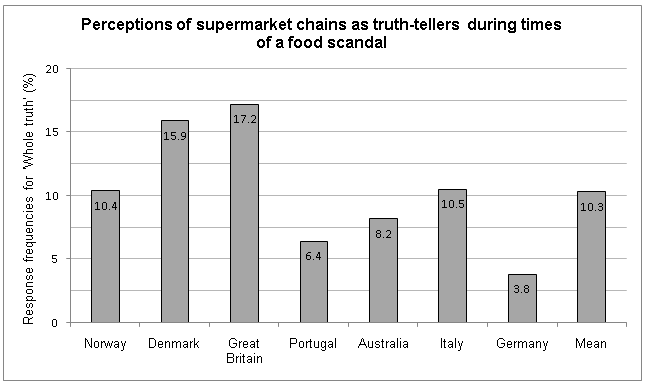

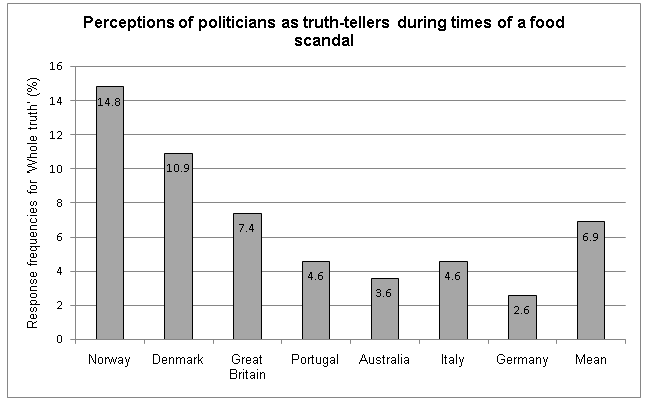

- The demographic details and respective frequencies of the Australian and European samples are given in table 2 5. Presented in table 3 2 are the percentages for European as well as Australian respondents who indicated their trust in the various individuals and institutions to tell the ‘Whole truth’ during a food scandal. Looking at the overall means for trust in truth-telling for each country included in the present analysis, Australian respondents occupy a place in the middle of the trust distribution, with an average of 14.25%of respondents having stated that the four bodies in question would tell the ‘Whole truth’. In comparison, Norwegian respondents exhibited the highest levels of overall trust in the truth-telling practices of the various bodies (24.6%), followed by Denmark (21.4%) and Great Britain (19.1%), while people in Germany reported the lowest levels of trust (10.4%). Mean trust scores in Portugal and Italy were similar to those in Australia; 15.5% of Portuguese respondents indicated their trust in the various individuals and institutions to tell the ‘Whole truth’, while 12.9% of Italian respondents stated the same.xxxTurning to the composition of the countries’ trust, i.e. how much respondents trust the separate bodies to tell the ‘Whole truth’ in times of a food scandal, a number of interesting patterns emerged which are presented graphically in figure 2. Starting with the mean trust score generated for each individual or institution in question across locations, the media (press, television and radio) were believed to be the most likely body to tell the ‘Whole truth’ during a food scandal, with an average of 32.1% of respondents across all countries sharing this view. The second most trusted entity in Europe and Australia are farmers (18.1% said these would tell the ‘Whole truth’), followed by supermarket chains (10.3%) in third place. Across countries, politicians are credited with the least amount of truth-telling, for only 6.9% of individuals across Europe and Australia stated that politicians would tell the ‘Whole truth’ during a food scandal.Establishment of a rank order of trusted institutions and individuals for each location3 revealed some remarkable similarities as well as differences between locations (table 4 3). In all countries bar two (Australia and Great Britain), the media received the most trust, while in all but one country (Norway) politicians were rated as the least forthcoming with the truth during a food scandal. Using the cross-country order observed for the mean trust scores for the four separate bodies (i.e. media, farmers, supermarket chains and politicians), the rank orders for Portugal and Germany were found to match the mean score ranks for every single individual or institution. In countries such as Norway, Denmark, Great Britain and Italy, two of the four bodies occupy the same position as observed for the mean score ranks. In Australia however, the way that trust is placed into truth-telling practices of individuals and institutions was quite different, and only the low frequency ratings observed for telling the ‘Whole truth’ by politicians match the average trust-distribution. In first position for Australia were farmers (also observed for Great Britain), in second place were supermarket chains (also true for Italy and Denmark), while the media came in third place of truth-tellers (not found for any other location).Turning the aforementioned rank order around and looking at the order in which the countries under investigation placed trust in the several individuals and institutions revealed further noteworthy differences (table 5 4, in conjunction with figure 3a). Norwegian respondents trusted the media to tell the ‘Whole truth’ most frequently (53.1%), a result juxtaposed by the very low frequency with which the media is believed to tell the ‘Whole truth’ in Australia (7.1%). Indeed none of the other countries show response frequencies that low, ranging between 45% observed in Denmark and a similar result in Portugal (41.1%) to frequencies of between 27.3% and 25.4% for Italy, Germany and Great Britain.

|

|

| Figure 2. Percentages of European and Australian respondents indicating the various individuals and institutions to tell the ‘Whole truth’ during times of a food scandal |

|

| Figure 3a. Percentages of respondents stating that the media would tell the ‘Whole truth’ during times of a food scandal, organized by country |

| Figure 3b. Percentages of respondents stating that farmers would tell the ‘Whole truth’ during times of a food scandal, organized by country |

| Figure 3c. Percentages of respondents stating that supermarket chains would tell the ‘Whole truth’ during times of a food scandal, organized by country |

| Figure 3d. Percentages of respondents stating that politicians would tell the ‘Whole truth’ during times of a food scandal, organized by country |

3.3. Summary of Australian Respondents’ Trust in Truth-telling Practices Relative to European Countries

- Apart from the fact that politicians are trusted the least in almost all countries under investigation including Australia, Australian respondents’ perceptionstowards the truth-telling practices of farmers, supermarket chains and the media were unique in terms of how they compare to the rank orders observed in other EU countries as well as the mean rank order of truth-tellers. Indeed, the relatively high proportion of Australian respondents who trusted farmers to tell the ‘Whole truth’ noticeably inflates the average trust score for farmers across countries, while the opposite holds true for including Australian frequency ratings for the media. For all truth-telling institutions as well as for politicians, Australian respondents’ trust in being told the ‘Whole truth’ was lower (in regards to percentages) than the mean trust frequencies across locations. It might therefore be suggested that the expectations of Australian respondents about how much of the truth they will be told during a critical period by a select set of individuals and institutions is quite different from how European respondents evaluate these bodies’ truth-telling practices.

4. Discussion

- Overall, respondents to this survey believed that the individuals and institutions in question would not tell the whole truth about a food scandal involving a commonly purchased and consumed food commodity. More than 90% of respondents said that the Australian media, supermarkets and politicians would ‘not tell the whole truth’. The results demonstrate a high level of distrust by the public in relation to the truth telling at a time of a food crisis. The most trusted to tell the whole truth during a food crisis in Australia were those considered to be at the top of the food production chain; that is, farmers. The reasons why farmers are considered to be more trustworthy in relation to a food scandal are unclear, although other work suggests that the Australia public might have a greater awareness of the actors involved with primary food production and farming activities[15]. Differences in overall levels of trust in truth-telling at times of a food scandal vary widely across Europe[15]. Trust in truth-telling may possibly reflect the political culture in each country. The political culture in Australia, like that in the UK, is based on a liberal democracy, rather than the social democratic structure found in Germany and Italy[16]. Moreover in countries such as Norway there is a more consensual process of politics, possibly leading to high trust in government. In other countries, such as Germany, political processes are more conflictual[17]. Australia, like the UK, has a largely adversarial political culture created by a tension between liberal individualism and democratic decision-making. These political systems tend to rely on outspoken opposition parties that are mandated to supposedly charged to ‘keep governments honest’. These processes may be responsible for the position of Australia within the field of European countries, making it closer to the UK rather than Nordic countries or Germany and Italy. Berg et al[18] note that regional differences in trust are a function not only of exposure to food scare and media reporting of scares, but also the perceived effectiveness of the strategies adopted to address these scares. Kjaernes discuss the ways in which some Scandinavian countries have developed powerful actors who have shown responsibility and control, leading to greater clarity of processes[17]. This may be responsible for higher levels of trust in these countries. Australia, on the other hand, has not experienced the food scares and scandals to the extent that these have been experienced in Europe. However, neither has there been high visibility of trusted food actors, especially from Australian government and government authorities. For example, in a study on people’s understanding of who is responsible for keeping food safe in Australia, few people were aware of the national food regulator, Food Standards Australia and New Zealand[19]. Turning to the position of food actors in truth-telling during times of a food scandal, farmers occupy the lead position in Australia, having more than four times the levels of trust than supermarket chains who were ranked in second place. In only one other country, Great Britain, are farmers similarly ranked in top place. The ascendancy of trust in food producers in the UK, especially after a number of high profile scandals, has been the subject of much comment. Wales et al[20] suggest that public confidence in food governance was strengthen by the transparency of processes introduced when the UK Food Standards Agency was established.In Australia the high ranking of farmers as trustworthy may be a result of not having to recover from problems of food safety and integrity at the level of food production. For example, Australia has never experienced foot and mouth disease, or other farm-based health and safety problems to the degree that has been the case in Europe[21]. However, the Australian public has not always been uncritical of food producers and farming interests. During debates in the late 1990s and early 2000s about the introduction into Australia of genetically modified organisms (GMOs), which were mostly confined to GM crops, mainstream Australian farming industries and the commercial interests that serviced them – such as large seed companies – came under scrutiny from public and public interest groups[22]. However, any lasting concerns do not appear to have transferred to the public’s view of farmers’ integrity within the context of the present study. The fact that the media had a high mistrust score is of interest. This is especially the case when other research has found that the public relies on media for information about food scares and scandals[6]. Also of interest is the level of trust conferred by Australians on their politicians in relation to truth-telling in times of a food scandal. As was the case for politicians in the European countries, Australian politicians ranked last, with only 7.1% of respondents believing that politicians would tell the whole truth. Quite why Australians see politicians as untrustworthy under these circumstances is unclear, although the adversarial nature of Australian politics in could arguably create greater levels of scepticism than under other political systems. Surveys have demonstrated that Australians generally view the political system as authoritarian and unresponsive, which may result in high levels of cynicism[23]. These reasons are likely to be different from those that might explain low levels of trust in politicians in southern European countries, where consumers gain trust from personal relationships, familiarity and food quality, rather than an impersonal institutional system[17]. The focus of this study on public perceptions of food chain actors’ truth-telling at times of a food scandal is particularly important in light of our current understanding of consumer trust in food. As de Krom&Mol,[24] point out, trust in food only obliquely derives from food-objects themselves; mostly, trust is conveyed by the agents who mediate between the food supply and food consumers: in other words, the food chain actors that have been the object of investigation in this and in the European study. Trust in these agents is, arguably, even more important in times of food crisis, such as during a food scare, when the public is reminded of its ‘non-knowing’ of certainties that may have been taking for granted[24].The results of this study suggest that food regulators in Australia need to consider carefully the channels of communication that are used when food problems arise in the food supply.

5. Limitations

- As a cross sectional survey, this study has a number of recognised weaknesses. Chief among these is the fact that this is an analysis of secondary data collected in Europe in 2002 and primary data collected in Australia in 2009. The EU survey questions were slightly different from the Australian questions, which may have influenced the dichotomised response categories. Another weakness is the 41% response rate for the Australian study, which although acceptable for this kind of survey, may have created the possibility of non-response bias. Further, due to self-reporting by respondents there may have been a degree of social desirability of responses. The use of Electronic White Pages (EWP) may have limited ability to contact mobile phone users who are not listed in EWP. Finally, the time points when data was collected in Australia (2009) and in Europe (2002) may have introduced temporal differences that my influence comparisons of truth-telling by food chain actors. In terms of strengths, to our knowledge this is the first study to have compared Australian and European data on consumer food trust, and as such, it represents a unique opportunity to compare and contrast public confidence in food chain actors in different cultural settings and different political environments. More broadly, we were able to compare public perceptions of truth-telling in countries that have experienced food scares and scandals, with those in Australia where experience of large scale food supply problems have largely been absent.

6. Conclusions

- This research has demonstrated that in Australia public trust in truth-telling at a time of a food scandal is low. This is consistent with the EU countries that are used as comparisons in this study. Individual country differences do exist, however, there are some clear patterns, for example, politicians being less trusted in all jurisdictions. The credibility of the food system – and those that are engaged - is highly vulnerable under times of food crisis. This is when the public turns to government, industry, media and politicians for advice on how to cope with the problem and reassurance that solutions are being sought. If at these times the public does not have trust in truth-telling then they might seek and believe alternative explanations and which might be a waste of resources, a waste of time, or even downright dangerous. And once public trust in broken, it is difficult to restore[25]. The fact that in this study consumers were asked to respond to a supposed food crisis might not accurately reflect their opinions when a real crisis occurs; obviously the actions of food chain actors during a food scandal episode can easily sway public opinion. However the results do suggest that efforts to bolster public trust in the governance of the food supply, especially given the low standing of politicians, would be a good investment.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- We would like to thank UnniKjærnes and Christian Poppe of SIFO, Norway for giving us access to data from the EU TrustinFood study, and for advice on this manuscript.

Notes

- 1. The European survey contained a further four entities to be rated in regards to their truth-telling practices.2. Includes responses in the form of ‘Not tell the truth at all’ and ‘Parts of the truth’.3. This rank order does not hold true for the European countries in absolute terms, since the European survey gathered information on four other entities not included in the Australian survey. As a result, the rank order of the four bodies analysed for the current investigation is only valid in the current circumstances, i.e. comparison of a select set of four individuals and institutions between Australia and European countries.

References

| [1] | BBC News. (2011). E.coli cucumber scare: Germany seeks source of outbreak. |

| [2] | deValk, V., Vaillant, V., Jacquet, C., Rocourt, J., Le Querrec, F., Stainer, F., et al. (2001). Two Consecutive Nationwide Outbreaks of Listeriosis in France, October 1999–February 2000. American Journal of Epidemiology, 154(10), 944–950. |

| [3] | Ansell, C., & Vogel, D. (2006). The contested governance of Eurpean food safety regulation. In C. Ansell & D. Vogel (Eds.), What's the beef? The contested governance of Eurpean food safety regulation pp. 2-32). Cambridge, Mass: MIT. |

| [4] | Wales, C., Harvey, M., &Warde, A. (2006). Recuperating from BSE: The shifting UK institutional basis for trust in food. Appetite, 47(2), 187-195. |

| [5] | Beers, M. (1996 ). Haemolytic-uraemic syndrome: of sausages and legislation. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health, 20, 462-466. |

| [6] | Coveney, J. (2007). Food and Trust in Australia:Building a picture. Public Health Nutrition, 11(3), 237-245. |

| [7] | Williams, P. G., Stirling, E., & Keynes, N. (2004). Food fears: a national survey on the attitudes of Australian adults about the safety and quality of food. Asia Pacific Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 13(1), 32-39. |

| [8] | Lupton, D. (2005). Lay discourses and beliefs related to food risks: An Australian perspective. Sociology of Health and Illness, 27(4), 448-467. |

| [9] | Henderson J, Coveney J, Ward P. Who regulates food? Australians' perceptions of responsibility for food safety. Australian Journal of Primary Health. 2010;16(4):334-51. |

| [10] | Coombes, R. (2005). Public distrusts government health campaigns, experts say. BMJ, 331, 70. |

| [11] | Kjærnes, U., Harvey, M., &Warde, A. (2007). Trust in food: A comparative and institutional analysis. Basingstoke: Palgrave, MacMillan. |

| [12] | deJonge, J., van Trijp, H., Jan Renes, R., &Frewer, L. (2007). Understanding Consumer Confidence in the Safety of Food: Its Two-Dimensional Structure and Determinants. Risk Analysis, 27(3), 729-740. |

| [13] | Kjærnes, U., Christian, P., &Lavik, R. (2005 ). Trust, Distrust and Food Consumption : A Survey in Six European Countries. . 15-2005, Oslo. |

| [14] | Kjærnes, U. (2009). Consumer trust in food under varying social and instutional conditions.NATO Advanced Research Workshop on Threats to Food and Water Chain Infrastructure (2008): NATO SCIENCE FOR PEACE AND SECURITY SERIES C: ENVIRONMENTAL SECURITY, 2010, SESSION I, 75-86, Springer 2009. |

| [15] | Henderson, J., Coveney, J., Ward, P., & Taylor, A. (2011). Farmers the most trusted part of the Australian food chain: results from a national survey of consumers. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Public Health,,35(4), 319-324. |

| [16] | Kjærnes, U., Harvey, M., &Warde, A. (2007). Trust in food: A comparative and institutional analysis. Basingstoke: Palgrave, MacMillan. |

| [17] | Emy, H. (1991). Organisation of a liberal democracy. In H. Emy& O. Hughes (Eds.), Australian politics: realities in conflict pp. 226-263.). Melbourne: McMillan. |

| [18] | Berg, L., Kjaernes, U., Ganska, E., Minia, V., Voltchkova, L., Halkier, B., et al. (2005). Trust in food safety on Russia, Denmark and Norway. European Societies, 7(1), 103-129. |

| [19] | Henderson, J., Coveney, J., & Ward, P. (2010). Who regulates food? Australians' perceptions of responsibility for food safety. Australian Journal of Primary Health, 16(4), 334-351. |

| [20] | Wales, C., Harvey, M., &Warde, A. (2006). Recuperating from BSE: The shifting UK institutional basis for trust in food. Appetite, 47(2), 187-195. |

| [21] | Lang, T., Barling, D., &Caraher, M. (2009). Food policy: integrating health, environment and society. Oxford: Oxford University Press. |

| [22] | Dietrich, H., &Schibeci, R. (2003). Beyond Public Perceptions of Gene Technology: Community Participation in Public Policy in Australia. Public Understanding of Science, 381-401. |

| [23] | Bean, C. (1993). Conservative cynicism: Political culture in Australia. International Journal of Public Opinion Research, 5(1), 58-77. |

| [24] | deKrom, M. P., &Mol, A. P. (2010). Food risks and consumer trust. Avian influenza and the knowing and non-knowing on UK shopping floors. Appetite, 55(3), 671-678. |

| [25] | Beers M. (1996).Haemolytic-ureamic syndrome: of sausages and legislation. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health 20, 453–45 |

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-Text HTML

Full-Text HTML