-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Food and Public Health

p-ISSN: 2162-9412 e-ISSN: 2162-8440

2012; 2(5): 159-167

doi: 10.5923/j.fph.20120205.07

Progressive Changes in Overweight and Obesity during the Early Years of Schooling among Children in a Central Region of Saudi Arabia

Abdulrahman Al-Mohaimeed 1, Mohammed Ismail 2, Khadija Dandash 1, Samir Ahmed 2, Muslet Al-Harbi 1

1Family and Community Medicine Department, College of Medicine, Qassim University, Mailing Address: College of Medicine Qassim University, Saudi Arabia , P.O. Box 6655 , Buraidah, 51452, KSA

2Food Science & Human Nutrition Department, College of Agriculture and Veterinary, Qassim University, P.O.Box 6622, Buraidah, 51452, KSA

Correspondence to: Abdulrahman Al-Mohaimeed , Family and Community Medicine Department, College of Medicine, Qassim University, Mailing Address: College of Medicine Qassim University, Saudi Arabia , P.O. Box 6655 , Buraidah, 51452, KSA.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

Childhood overweight and obesity have become a global public health problem. This study aims to determine the prevalence of these health conditions in children studying in government schools in the two cities of Buraidah and Unaizah of the Qassim Region, Saudi Arabia. The key question that we examined was whether the children enter the school as overweight or become overweight after entering the school. Using a cross-sectional, observational study design, a random sample of 874 school children between 6– to 10 years was enrolled in 2010/2011. A structured questionnaire was used for collecting data. Weight and height were measured, and the body mass index (BMI) was categorized. Based on the World Health Organization (WHO) definition, the overall prevalence of overweight and obesity was 12.8% and 10.1%, respectively. Girls had a higher prevalence of overweight (18.4%) and obesity (15.6%) than boys. Overweight tendency increased dramatically from 7.6% in Grade 1 to 19% in Grade 4. Similarly, obesity also increased progressively after entering the school. Our study suggests that overweight and obesity are mostly acquired after entering the school. Public health program are, therefore, required to promote a healthy lifestyle from the early years of schooling.

Keywords: Childhood, Overweight, Obesity, BMI, Saudi Arabia

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Studies from different parts of the globe indicate a high prevalence of overweight and obesity among children in both developed and developing countries. Saudi Arabia ranks 29 on the 2007 list of countries with fat individuals with 68.3% of its citizens being overweight and obese.[1] Of the 13 provinces that constitute Saudi Arabia, Qassim ranks the third with a high prevalence of obesity (26.5%) ranging between 11.7-33.9%.[2]Overweight and obesity are defined as abnormal or excessive fat accumulation in the body that may impair health. Obesity is a complex and incompletely understood condition. It is not just an individual’s problem but a public health issue and therefore must be tackled accordingly.[3] Globally, obesity is the fifth leading cause of death.[4] Childhood obesity is a global problem. Its prevalence continues to increase at an alarming rate. It has become one of the most serious public health challenges of the 21st century.[5] Globally, 10% of school-aged children, between 5 and 17 years, are overweight or obese, and the situation is getting worse.[6] A review of data on childhood obesity for Saudi Arabia shows interesting variations. The results of the national household screening on diabetes mellitus (1994 to 1998) revealed overweight and obesity as 13.6% among males and 17.8 % among females in 6-12 years children.[7] The recent work on the 2005 reference national based data of 19317 healthy children and adolescents from 5 to 18 years showed an overall prevalence of overweight, obesity and severe obesity as 23.1%, 9.3% and 2%, respectively with a total of 34.3 %. These studies also showed that children between 6-13 years of age in the Qassim region have higher prevalence of overweight and obesity than the similar group in South Western and Northern regions.[8, 9] Childhood overweight and obesity are strongly associated with the risk of developing high cholesterol, hypertension, respiratory ailments, orthopaedic problems, depression and type 2 diabetes.[10] Overweight and obesity are affected by various genetic, behavioural, and environmental factors.[11] Examination of these factors is therefore crucial for providing insights into preventive actions.[12] The management of overweight and obesity in children should not be delayed until adulthood because then it becomes ever more difficult to achieve lasting weight reduction. Adiposity measurement methods are variable. Body mass index (BMI) is simple anthropometric measure and has been a valuable tool for monitoring trends in obesity.[13-18] The aim of this study is to assess the prevalence of overweight and obesity among young school children of 6-10 years in two big cities of Qassim, Saudi Arabia. We purposefully selected the capital city which constitutes 50 % of Qassim’s population. The other was selected randomly from the remaining ten cities. The reason for selecting 6-10 year cohort was to observe and better understand the progression process of overweight and obesity against the background of their entry into an ‘external environment of exposure to food’ outside their homes. The age group of over 10 years was not selected to avoid effects of hormonal changes on BMI that could result from menarche.[19] A key question that we examined was whether the children enter the school system as overweight or become overweight after entering the school. To address this issue we explored if the prevalence of overweight and obesity increased with age or remained the same from the early ages as the children entered the school system.

2. Methodology

- This was a cross-sectional study carried out in the Qassim region and data were collected using a multi-staged survey sampling method. We targeted students between 6-10 years studying in the first four years of the public sector primary schools.. A review of the global studies reports the prevalence rates of overweight, including obesity, to vary between 23% to 46.0 %[20]. For calculating our sample size, we applied a conservative approach of using 50% as the prevalence rate of overweight, which would give the largest required sample. At 95% confidence level, with 5% margin-of-error, a design effect of 2.0 for clustered data at the school level and 12% non-response rate, we estimated the sample size requirement of 874. Hence, the study targeted to interview 874 students. As the first step the capital city, Buraidah, which makes nearly 50% of the population of Qassim was selected. Unaizah was the other city randomly selected of the ten main cities of Qassim..The second stage was of random selection of targeted schools. From a current list of primary schools in the two cities, and according to proportional allocation, 30 schools from Buraidah and 4 from Unaizah were randomly selected to represent nearly 10 % of total targeted schools. In the third stage an ordered list of classes of the targeted fourth graders in the selected schools was used to represent the sampling frame. As the average number of students per class was around 25, a total of 40 classes were included to reach the required sample size. Ten classes from each grade were randomly selected. All students in the class (cluster) were invited to participate. Thus the study covered 874 students who were present in the selected classes at the time of data collection. The selected students fulfilled the inclusion criteria of being native Saudis; registered in the primary national schools; age 6-10 years and permanent residents of Qassim. Using the school health records we excluded physically disabled children, i.e. those having any chronic disease or any psychiatric or an immune-compromised disorder. The survey was conducted between February and June 2011.

3. Data Collection Tools and Techniques

- After a brief orientation, selected school children were subjected to the following:

3.1. Anthropometric Measurements

- All measurements were carried out outside the class room. The students were measured bare feet and with light clothes. The weight was measured using a portable commercial balance (Seca, Germany) with an accuracy of ±100 g. The students stood erect and without touching anything. The recorded weight was approximated to the nearest 0.5 kg (Jellify, 1989). The height was measured using a portable stadiometer. The students stood on the platform with feet parallel and the back of the head, back; buttocks, calves and heels touching the upright surface. The standing body height was measured to the nearest 0.5 cm.[22] The scales were recalibrated after each measurement. 1) BMI was calculated as 'body weight in kilograms/height in meters, squared. We applied the cut-off points of overweight: >+1SD (equivalent to BMI 25 kg/m2 at 19 years), Obesity: >+2SD (equivalent to BMI 30 kg/m2 at 19 years), Thinness: <-2SD and Severe thinness: <-3SD which are recommended by WHO[23] in identifying the age and gender-specific cut-off points for the BMI with the age ranging from 5 to 19 years for the diagnosis of overweight and obesity among the subjects. BMI indirectly assesses the amount of body fat.[15] We used the standard WHO definition for the sake of comparability of the results to studies in other regions and comparable countries.

3.2. Questionnaire Construction

- It included the following items:a. Sociodemographic data: These were collected using a parental form and included the following items: Name of the school; class level; socioeconomic data; parental age, education, and occupational status; current residence, and family size. b. Medical history: This included health status of the student, and his/her past history of surgeries, medical conditions and any previous use of medicines. It also included family history of general health and obesity.Finally, all questions were reviewed by a group of five experts in the field, and modified according to their recommendations.

3.3. Pilot

- The questionnaire was piloted on a small sample of the students to identify the areas in need of improvements.

3.4. Administration of the Questionnaire

- This was done by handing the questionnaire over to the students attached with a covering letter as mentioned above, students then had to bring the filled out questionnaire back to the school’s social worker.

3.5. Data Management and Data Processing

- Statistical Package Social Science; SPSS version 17 software (SPSS Inc. Chicago, Illinois, USA) was used for data entry and processing. Exploratory data analyses were performed for examining the quality of data and distribution of the variables. Inferential data analyses were conducted using the appropriate statistical tests of significance. We reported the prevalence rates and 95% confidence intervals of overweight and obesity. A significance level of 0.05 was used for assessing the statistical differences between subgroups. Differentials in overweight and obesity were examined for socio-demographic variables. Multivariable logistic regression models were used to identify the major determinants of overweight or obesity, adjusted for other confounding covariates.

3.6. Ethical Considerations

- The Regional Education Directorate and School Health Authorities, along with the teaching and administrative staff of schools, were taken onboard about the study objectives and methods. Before commencing interviews and measurements, the students were given a brief orientation. The study protocol was approved by the Research Committee of Qassim University.

4. Results

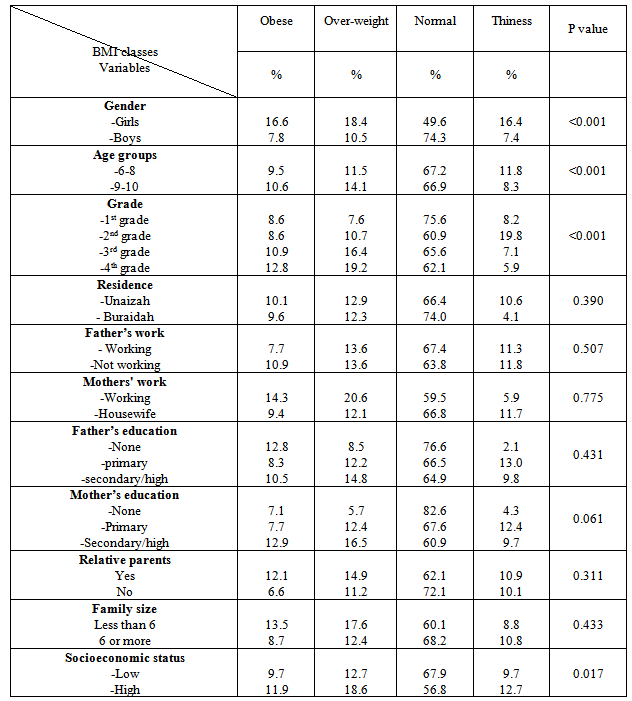

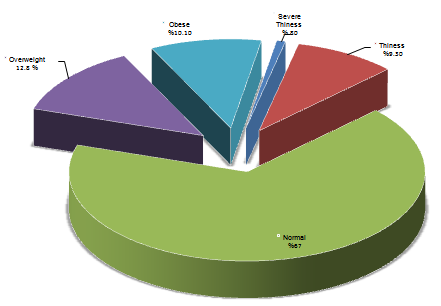

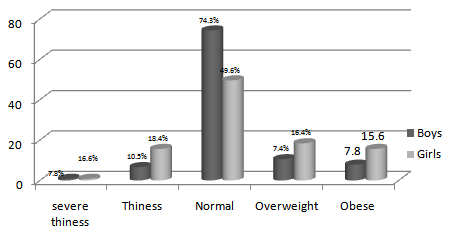

- Our sample consisted of 874 students (boys and girls). Boys represented 70.7 % (n=618) and girls the rest of 29.3% (n= 256). The mean age of boys was 8.2 ± 1.28 SD with a range of 6-10 years and for girls it was 8.7 ± 1.14 SD with a range 7-10 years. The response rate for the first set of data collection was 100% and to the second 92.0% (804 out of 874 students).[Table 1]Table 2 shows the summary measures of height, weight and BMI. Girls showed a highly significant difference from boys in both weight and height (P value=0.001). The mean of BMI of boys was 16 ± 2.6 with a range 12.1 to 31.1, and that of girls was 17.9 ± 4.3 with a range 8.4 to 41.3 as they showed a highly statistically significant difference than boys (P=0.001). The detailed distribution of overweight and obesity as per International Classification of WHO based on BMI is shown in Fig. 1. Overweight and obesity were observed in 12.8 % (112 students) and 10.1% (88 students) of the students, respectively whilst the majority of the sample was within the normal range. It is also important to note that 10.1 % (n=88) students had either severe thinness or ordinary thinness, indicating a sizeable proportion of malnutrition among Saudi Arabian children. The differentials in overweight, obesity and underweight by demographic and socio-economic characteristics were shown in Table 3. Only 7.6% of the children were overweight in the first grade, while 19.2% of them were so in the 4th grade. Similarly 8.6% of them were obese in the first grade while 12.8 of them were so in the 4th grade.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| Figure 1. Distribution of children according to WHO’s classification of overweight and obesity based on BMI |

|

| Figure 2. The differentials in overweight and obesity by gender |

5. Discussion

- Childhood obesity has become one of the most serious public health challenges of the 21st century.[5] The results of our study support this contention by demonstrating the emergence of a highly increasing prevalence of overweight and obesity among school children. It showed that overweight and obesity affected about half of our sample. It is in line with the global trends; in the USA, the problem more than tripled in the past thirty years.[24] Positive economic growth and the associated affluence, urbanization, modern amenities, fast food culture and lack of physical activity could be the main variables responsible for the emergence of obesity in the Saudi population. This premise is supported by Popkins[25] who attributed the increase rates of overweight and obesity in developing countries to radical and rapid changes in life-style.Another notable feature was that results of our study exceeded the increase recorded in overweight and obesity rates in similar age groups in the gulf region, e.g. Kuwait (37.0 %), Qatar (23.3 %) and UAE (26.4 %)[26, 27, 28], countries that have undergone similar economic upturn. This aspect supports our hypothesis that advancing time has had an amplifying effect on these two factors, which is a great cause for concern and needs to be checked through effective and immediate public health interventions. However, Iran appears to be an exception to this general trend but only in terms of severity of the problem. Iran showed much lower rates of obesity and overweight[29], perhaps, due to the sanctions and embargoes adversely affecting the Iranian economy.Additionally, our study results also exceeded the reported rates in the two main previous national studies in 2002 (31.4%) and 2005 (34.3%).[7, 8] These variations in the rates in the gulf region could be attributed to the lack of consistency and agreement among different studies on the classification of obesity in children, in addition to differences in study designs and sampling methods. The difficulty and limitations in comparisons of prevalence of overweight and obesity among children have already been indicated in WHO’s report[3] and by Story et al.[30] This study used the WHO’s definition and classification of obesity.[22] The study design was cross-sectional with a randomly selected cluster sample suited to achieve its objectives. Nonetheless, all studies have categorically recorded increasing trends in rates of obesity and overweight.Childhood obesity is not caused by one factor alone; rather it results from the interplay of multiple factors. Regarding the factors associated with occurrence of overweight and obesity in the elementary school-aged children, the problem appears to affect girls more than boys. Results of logistic regression revealed the predominance of being a girl as a risk factor for occurrence of the problem at this age. In the gulf region the predominance of the problem of obesity among girls appeared in Bahrain and UAE as well.[27, 31, 32] In contrast, more boys were overweight and obese than girls in Qatar. [26] Preponderance of sedentary lifestyle as a result of affluence has reduced physical activity in the gulf region. Young school students spend more time in front of computers, TV and with iPods, iPads and tablets at the expense of physical activities. Similarly, girls spend most of their out-of-school time at home with hardly any physical activity making them prone to becoming overweight and obese. These observations have also been recorded in European countries. Swedish researchers attributed the problem of overweight or obesity in young girls, who were affected more than boys of the comparable age, to the time spent in front of televisions and computers that tended to reduce the physical activity.[33] Girls, therefore, increasingly demonstrate a sedentary behavior pattern than boys of their age group.[34]The examination of the relationship of overweight and obesity with age in our study showed a positive trend, progressively increasing with age after the children joined the school. These finding could be due to the exposure of children to an external environment where their diet habits changed or they were exposed to more fatty diets. These results are supported by the study of Al Isa[28] among Kuwaiti children of the same age group. Another study conducted in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia showed a prevalence of obesity of 10.8 among preschool children.[35] Furthermore, there was a statistically significant association of advancing grade years, and overweight and obesity rates. This was an additional indicator supporting the progression of the problem with the increasing age. However, there are studies with contradictory findings as well. Booth et al,[36] in Australia reported no relationship between school grade and fatness. To the contrary, the youngest age cluster (6 year old) values were unusual in our study. The rates of overweight and obesity by both measures were higher than older age clusters (7th and 8th clusters). This could be a negative indicator highlighting the susceptibility of the younger generations to the problem of obesity.Interestingly, we found out that parents’ employment and level of education was associated with adiposity. Students whose mothers were employed and had a relatively higher level of education showed a tendency towards overweight and obesity. However, in logistic regression modelling, this role lost its weight, which probably makes this finding incidental. In the Saudi population the highly educated working women have to face competing demands of work and family. In this situation providing home cooked healthy meals to children is difficult, who invariably resort to junk food, therefore, exposing themselves to the risk of overweight and obesity. The connection between mothers’ work, earnings and the occurrence of overweight and obesity in children has been reported in a number of studies.[37, 38, 39, 40] Our results indicated that family size has a bearing on the occurrence of overweight and obesity. The smaller sized families showed a significant increase in the percentages of overweight and obesity than larger families, therefore, showing an inverse relationship between the size of the family and obesity/overweight. Although our results showed a significant association of small sized families with the problem of obesity, it lost its significance in logistic regression modelling. This could be attributed to the link between the small sized family with a higher socioeconomic status that is associated with high rates of overweight and obesity. These results agreed with Padez’s cross sectional study of Portuguese children of 7 to 9.5 years that reported that being a single child was significantly associated with overweight and obesity. The same trend was seen regarding the number of siblings in the family and the order of birth; children from big families and those born later presenting a lower risk of being overweight or obese.[41] However, household size and income are negatively related to the child’s weight but the relationship is weak.[31] Socioeconomic status (SES) of the family was yet another factor that impinged on obesity and overweight. Our study results indicated that overweight/obesity was significantly higher among the students belonging to the higher socioeconomic group, thus, establishing a positive relationship between the socioeconomic status of the family and obesity. Families with a higher disposable income tend to spend more on food and life comforts without really visualizing their health consequences. Similar results have been reported by a global study that compared prevalence of overweight and obesity in school-aged youth from 34 countries and reported particularly high prevalence in affluent countries of North America, the UK, and South-western Europe.[42] In India, the prevalence of obesity and overweight increased significantly with the increasing income.[43] A similar picture was seen in Egypt, where the prevalence of obesity among high SES adolescents was more than double than that among low SES groups.[44] However, a different trend has also been observed. Over the last three decades, the prevalence of overweight and obesity was greater in lower-middle- and low-income countries than in upper-middle and high-income countries, with rates of obesity doubling over the three decades between 1980 and 2008.[45] Surveys of school children from poor families report higher intake of fat, lower intake of complex carbohydrates and lower intake of some micronutrients.[46, 47]

6. Limitations of this Study

- Our study had some limitations. Our sample did not include private schools and schools from rural areas. Data collection was done at two levels; firstly, by direct measurement of the student obesity indices at the school and getting the socio-demographic background information by a self- reported questionnaire from students’ parents. This procedure raised the non-response rate of the questionnaire part. It created incongruity between the numbers of the two variables. Moreover, self- reported data had a likelihood of biasness and inaccuracy, especially in data related to income and parents’ educational level. Moreover, this study is based on cross-sectional data and the temporal changes in weight could not be determined to assess progression to overweight at an individual level.

7. Conclusions

- The results of our study demonstrated the emergence of an increasing prevalence of overweight and obesity among Saudi school children resulting from radical and rapid changes in life-style owing to economic growth. Smaller size of the family and higher socoi-economic status contributed more to the development of these conditions. Interestingly, overweight and obesity were mostly acquired after entering the school. The problem increased progressively with the increasing age due to the exposure of students to the ‘external food environment’ as against home-cooked meals. It emphasizes the urgent need of effective interventions to offset the problem from the early years after entering the school. Results also suggested the presence of the problem of underweight among few children which should be further investigated and addressed.

Conflict of Interests

- The authors declare that they have no conflict of interests.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- This study was made possible by a research grant from the Deanship of Research Qassim University, Saudi Arabia, and was conducted with the permission from the Ministry of Education, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. The authors are fully responsible for the contents of the study. Views expressed here are not necessarily those of the Ministry of Education, Deanship of Research or Qassim University. We are indebted to the staff of the schools involved for their cooperation and assistance in data collection. We also thank Dr. Saifuddin Ahmed from Johns Hopkins University for reviewing the manuscript.

References

| [1] | Streib L. (February 8, 2007). Forbes "World's Fattest Countries". Forbes. Available at: http://www.forbes.com/2007/02/07/worlds-fattest-countries-forbeslife-cx_ls_0208worldfat_2.html Forbes. Retrieved 26-4-2012. |

| [2] | Al-Othaimeen AI, Al-Nozha M, Osman AK. Obesity: an emerging problem in Saudi Arabia. Analysis of data from the National Nutrition Survey. East Mediterr Health J, vol.13, no.2, pp 441-8. 2007 Mar-Apr. |

| [3] | World Health Organization: Obesity preventing and managing the global epidemic. Report of WHO consultation on obesity .WHO Technical Report Series 894: Geneva, World Health Organization, 2000. |

| [4] | James WPT, Jackson-Leach R, Mhurchu CN, Kalamara E, Shayeghi M, Rigby NJ, Nishida C, Rodgers A: Overweight and obesity (high body mass index). In Comparative quantification of health risks: global and regional burden of disease attributable to selected major risk factors. Edited by: Ezzati M, Lopez AD, Rodgers A, Murray CJL. Geneva, World Health Organization, pp.497-596, 2004. |

| [5] | World Health Organization: Fight childhood obesity to help prevent diabetes, say WHO & IDF. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/news/releases/2004/pr81/en/ access 26/4/2012 |

| [6] | International Obesity Task Force data, based on population weighted estimates from published and unpublished surveys, 1990–2002 (latest available) using IOTF-recommended cut-offs for overweight and obesity. available at: [http://www.iotf.org]. |

| [7] | El-Hazmi M, Warsy AS. The prevalence of obesity and overweight in 1-18-year-old saudi children. Ann Saudi Med, vol.22, no.5-6, pp303-307, 2002. |

| [8] | El Mouzan MI, Foster PJ, Al-Herbish AS, Al-Salloum AA, Al-Omer AA, Qurachi MM, and Kecojevic T. Prevalence of overweight and obesity in Saudi children and adolescents. Ann Saudi Med, vol.30, no.3, pp 203–208. 2010 May-Jun. |

| [9] | El Mouzan MI, Al Herbish AS, Al Salloum AA, Al Omar AA, Qurachi MM. Regional variation in prevalence of overweight and obesity in Saudi children and adolescents. Saudi J Gastroenterol, vol.18, pp129-32, 2012. |

| [10] | Dietz WH. Health consequences of obesity in youth: childhood predictors of adult disease. Pediatrics, vol.101, pp518–525. 1998 |

| [11] | Daniels SR, Arnett DK, Eckel RH, et al. Overweight in children and adolescents: pathophysiology, consequences, prevention, and treatment. Circulation, vol.111, pp. 1999–2002. 2005 |

| [12] | Guo S.S.; Roche, A.F.; Chumba,W.C.; et al. The predictive value of childhood body mass index values for overweight at age 35 years. Am.J. Clin. Nutr, vol.59, pp.810-819, 1995. |

| [13] | Rees JM. Management of obesity in adolescence. Med Clin North Am, vol.74, pp. 1275–92, 1990. |

| [14] | Prentice AM, Jebb SA. Beyond body mass index. Obes Rev, vol.2, pp.141–147, 2001. |

| [15] | Amy Luke, Ramon Durazo-Arvizu, Charles Rotimi, T. Elaine Prewitt, Terrence Forrester, RainfordWilks, Olufemi J. Ogunbiyi, Dale A. Schoeller, Daniel McGee, and Richard S. Cooper. Relation between Body Mass Index and Body Fat in Black Population Samples from Nigeria, Jamaica, and the United States. Am J Epidemiol, vol. 145, no.7, pp.620-28, 1997. |

| [16] | Cole TJ, Bellizzi MC, Flegal KM, Dietz WH. Establishing a standard definition for child overweight and obesity worldwide: international survey. BMJ, vol.320, pp.1240–3. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7244.1240. 2000 |

| [17] | Eisenmann JC, Heelan KA, Welk GJ. Assessing body composition among 3 to 8 year-old children: anthropometry, BIA, and DXA. Obes Res, vol.12, pp.1633-40, 2004. |

| [18] | Steven Garasky, Susan D. Stewart, Craig Gundersen, Brenda J. Lohman Joey C. Eisenmann. Family Stressors and Childhood Obesity. March 7, 2008 Paper presented at the 2008 Population Association of America Annual Meeting in New Orleans, LA, April 17-19, 2008. |

| [19] | Babay ZA, Addar MH, Shahid K, Meriki N. Age at menarche and the reproductive performance of Saudi women. Ann Saudi Med, vol.24, no.5, pp. 354-356, 2004. http://www.kfshrc.edu.sa/annals/articles/24_5/03-323.pdf |

| [20] | Wang Y, Lobstein T. Worldwide trends in childhood overweight and obesity. Int J Pediatr Obes, vol.1, no.1, pp.11-25, 2006. |

| [21] | World Health Organization: Guidelines on Nutrition Survey Methodology in Uganda Part A. Geneva: World Health Organization, 1988. |

| [22] | WHO Measuring obesity classification and description of anthropometric data. Copenhagen: WHO Regional office for Europe. 1989. |

| [23] | WHO Growth reference 5-19 years. June 2009. BMI-for-age (5-19 years) http://www.who.int/growthref/who2007_bmi_for_age/en/index.html Access 1/5/2011 |

| [24] | Ogden, CL, Flegal KM, Carroll MD, and Johnson CL. Prevalence trends in overweight among US children and adolescents 1999-2000. Journal of the American Medical Association, vol.288, pp.1728-1732, 2002. |

| [25] | Barry M. Popkin. The Nutrition Transition and Obesity in the Developing World. J. Nutr, vol.131, no.3, pp.871S-873S, March 1, 2001. |

| [26] | Davallow L, Abou Ayash H, El-Assad I and Khidir A. The prevalence of obesity amongst school children and adolescents in Qatar. Weill Cornell Medical College in Qatar, Doha, Qatar, available at: http://www.qscience.com/doi/pdf/10.5339/qfarf.2011.bmos4 |

| [27] | Al-Haddad F, Al-Nuaimi Y, Little BB and Thabit M. Prevalence of obesity among school children in the United Arab Emirates. AMERICAN JOURNAL OF HUMAN BIOLOGY, vol.12, pp.498–502, 2000. |

| [28] | Al-Isa AN, Campbell J, and Desapriya E. Factors Associated with Overweight and Obesity among Kuwaiti Elementary Male School Children Aged 6−10 Years. International Journal of Pediatrics, Vol. 2010, Article ID 459261, 6 pages, 2010. |

| [29] | Taheri F and Kazemi T. Prevalence of Overweight and Obesity in 7 to 18 Year old Children in Birjand/ Iran. Iranian Journal of Pediatrics, Vol.19, No.2, pp. 135-140, June 2009. |

| [30] | Story M, Evans M, Fabsitz RR, Clay TE, Holy Rock B, Broussard B. The epidemic of obesity in American Indian communities and the need for childhood obesity-prevention programs. Am J Clin Nutr, vol.69, (4 Suppl), pp.747S-754S, 1999 Apr. |

| [31] | Garasky, S., Stewart, S., Lohman, B., Gundersen, C., & Eisenmann, J. Family stressors and childhood obesity. Social Science Research, vol.38, pp.755-766, 2009. |

| [32] | Sendi AM, Shetty P and Musaiger AO. Prevalence of overweight and obesity among Bahraini adolescents: a comparison between three different sets of criteria. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition, vol.57, pp. 471–474, 2003. |

| [33] | Holmbäck U, Fridman J, Gustafsson J, Proos L, Sundelin C and Forslund A. Overweight more prevalent among children than among adolescents. Acta Paediatrica, vol.96, pp. 577-581, April 2007, Article first published online: 22 MAR 2007 |

| [34] | Epstein LH, Roemmich JN, Paluch RA, and Raynor HA. Physical activity as a substitute for sedentary behavior in youth. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, vol.29, no.30, pp. 200– 209, 2005. |

| [35] | Al-Hazzaa H, Al-Rasheedi A. Adiposity and physical activity levels among preschool children in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia.Saudi Medicak J, vol.28, no.5, pp. 766-73, 2007. |

| [36] | Booth ML, Macaskill P, Lazarus R, Baur LA. Sociodemographic distribution of measures of body fatness among children and adolescents in New South Wales, Australia. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord, vol.23, no.5, pp.456-62, 1999 May. |

| [37] | Anderson, P, Butcher, K., & Levine, P. Maternal employment and overweight children. Journal of Health Economics, vol.22, pp.477-504, 2003. |

| [38] | Fertig, A., Glomm, G., &Tchernis, R. The connection between maternal employment and childhood obesity: Inspecting the mechanisms. Review of Economics of the Household, vol.7, pp. 227-255, 2009. |

| [39] | Ruhm C. Maternal Employment and Adolescent Development. Labour Economics, vol.15, pp. 958-983, 2008. |

| [40] | Hajian-Tilaki K. and Heidari B. Association of educational level with risk of obesity and abdominal obesity in Iranian adults. J Public Health, vol.32, no.2, pp. 202-209, 2010. |

| [41] | Padez C, Mourao I, Moreira P, & Rosado. V. Prevalence and risk factors for overweight and obesity in Portuguese children. Acta Paediatrica, vol.94, pp. 1550-1557, 2005. |

| [42] | Janssen I, Katzmarzyk PT, Boyce WF, Vereecken C, Mulvihill C, Roberts C, Currie C, Pickett W. Health Behaviour in School-Aged Children Obesity Working Group. Comparison of overweight and obesity prevalence in school-aged youth from 34 countries and their relationships with physical activity and dietary patterns. Obes Rev, vol.6, no.2, pp.123-32, 2005 May. |

| [43] | Kaur S, Sachdev HPS, Dwivedi SN, Lakshmy R, Kapil U. Prevalence of overweight and obesity amongst school children in Delhi, India. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr, vol.17, no.4, pp.592-596, 2008. |

| [44] | Ibrahim BL, Sallam S, El-Tawila S, El-Gibaly O, El-Sahn F, Lee SM, Mensch BS, Wassef H, Bukhari S and Galal O. Transitions to adulthood: a national survey of Egyptian adolescents. Cairo, Population Council, pp.25– 30, 1999. |

| [45] | Black RE, Cousens S, Johnson HL, Lawn JE, Rudan I, Bassani DG, Jha P, Campbell H, Walker CF, Cibulskis R, Eisele T, Liu L and Mathers C. Global, regional and national causes of child mortality in 2008 : a systematic analysis. The Lancet, vol.375, pp.1969–1987, June 2010. |

| [46] | Devaney, B. L., Gordon, A. R. &Burghart, J. A. Dietary intakes of students. Am. J. Clin. Nutr, vol.61,(suppl.), pp.205S–212S, 1995. |

| [47] | Laitinen S., Rasanen L., Viikari J., Akerblom H. K. Diet of Finnish and physical activity in relation to indexes of body fat: the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute Growth and Health Study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr, vol.60, pp.15–22, 1995. |

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-Text HTML

Full-Text HTML