-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Food and Public Health

p-ISSN: 2162-9412 e-ISSN: 2162-8440

2012; 2(5): 119-126

doi: 10.5923/j.fph.20120205.01

Physical Activity Perceptions and Binge Eating Disorder in Community Dwelling Women

Jason Crandall 1, Patricia A. Eisenman 2, Lynda Ransdell 3, Justine Reel 4

1Department of Kinesiology & Health Promotion, Kentucky Wesleyan College, 3000 Frederica Street, Owensboro, 42301, Kentucky

2FACSM, Department of Exercise & Sport Science, University of Utah

3FACSM, CSCS, Department of Kinesiology, Boise State University

4LPC, CC-AASP, Department of Health Promotion & Education, University of Utah

Correspondence to: Jason Crandall , Department of Kinesiology & Health Promotion, Kentucky Wesleyan College, 3000 Frederica Street, Owensboro, 42301, Kentucky.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

Binge eating disorder (BED) is characterized by recurrent binge eating without compensatory weight control methods[1]. Physical activity (PA) may be an innovative adjunct treatment for BED. Researchers have described PA involvement in BED individuals throughout their life spans[2]. Significant differences in PA were found during specific time periods when compared to controls. Significant differences were found for six perceived benefits/barriers to physical activity. The objective of this study was to apply qualitative research methodologies to enrich our understanding of the quantitative data. The interview participants reporting perceived barriers including social physique anxiety, health problems, compulsive issues, lack of fitness, lack of time, social barriers, and access. Perceived benefits included improved psyche, removal of frustrations, increased stamina, improved confidence and physical health. Emphasizing unstructured home-based and family-oriented PAs and including enjoyable structured activities may increase adherence levels in BED individuals.

Keywords: Binge Eating, Physical Activity, Eating, Binge Eating Disorder, Exercise Jason Crandall, Ph.D.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Binge eating disorder (BED) is characterized by recurrent binge eating episodes without compensatory weight control methods such as vomiting, laxatives, or excessive[1]. Because of the lack of compensatory behaviors, overweight and obesity are common comordidities[1]. The estimated prevalence of BED in the general population is between 0.7% and 3.0%[3]. Cognitive behavioral therapy, intrapersonal, pharmacological, and behavioral weight-loss therapies have been used alone or in combination to treat individuals meeting the diagnostic criteria for BED[4]. Researchers have suggested physical activity (PA) may be an innovative and widely disseminated treatment that could affect biopsychosocial outcomes for patients with eating disorders[5]. Levine and Marcus also concluded treatment approaches that focus on nutrition education, moderate caloric restriction, and moderate exercise may decrease binge eating episodes and may promote weight loss in obese binge eaters[6]. Pendleton and colleagues used leisure time structured exercise in conjunction with cognitive behavioral therapy[7]. They found significant reductions in binge eating episodes and body mass index as well as significant improvements in mood. Although evidence of the positive benefits of PA for the treatment of BED seems clear, the necessary dose-response relationship as well as effective behavioral techniques to improve PA adherence have not been clearly elucidated. PA adherence is an important area of research in all segments of the population due to the abysmal adherence rates for most PA interventions. Perceived barriers may contribute to poor adherence to PA interventions among specific population subgroups. Until recently, the perceived barriers to exercise and PA habits of BED participants were unknown. Crandall and colleagues described how PA involvement changes in BED individuals throughout their life spans[2]. Females (N=312) were recruited within the continental United States and self-administered questionnaires. BED participants (n=18), subclinical BED participants (n=19), and non-BED overweight controls (n=19) were identified. BED individuals reported lower PA levels during the young adult and mature adult periods when compared to non-BED body weight matched controls. Significant differences were found between BED individuals and controls for six exercise benefits and exercise barriers questions (p < .05). BED individuals have lower PA compared to controls during periods of the life span, and exercise benefits and barriers are significantly different. BED participants’ specific barriers to exercise were (a) clothes made them look funny; (b) exercise programs cost too much; (c) exercise took too much time in general and away from their families; (d) there were too few places to exercise; (e) their families did not encourage them to exercise; and (f) facilities’ schedules were inconvenient. Although these results contribute to one’s understanding of PA in the lives of BED individuals, there is much that needs further explanation. Specific barriers need to be addressed if PA is to be used as an adjunct treatment for BED individuals.

2. Objectives

|

|

3. Methods

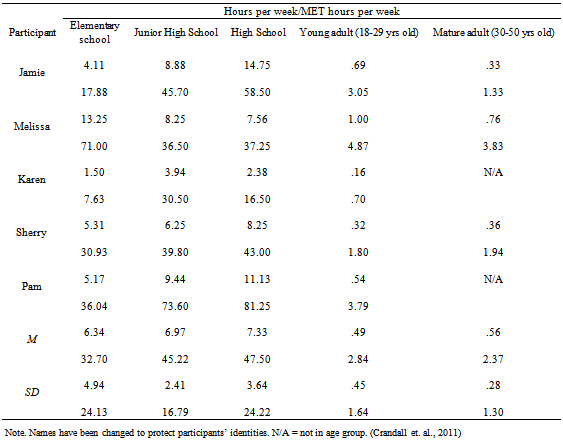

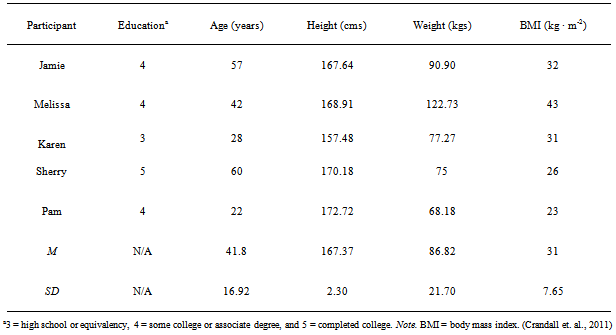

- To explain more fully our understanding of PA in the lives of BED individuals, semistructured interviews were conducted with 5 of the 18 BED participants from the initial study by Crandall and colleagues[2]. Tables 1 and 2 contain the PA and demographic characteristics of the 5 volunteers. The names of the participants were changed to protect their identities. Prior to data collection, approval was obtained from the University of Utah Institutional Review Board. Participants gave additional informed consent forparticipation in the semistructured interview. In conjunction with a nationally certified counsellor, semistructured interviews were conducted. Each participant was interviewed between 35 and 60 minutes. Both deductive and inductive approaches were used to develop the interview guide and data analysis. A deductive approach uses predetermined themes and categories to organize data, whereas an inductive approach allows themes and categories to emerge from the data. A deductive approach was used in the construction of the interview guide. The interview guide was constructed around three general topics: (a) PA perceptions; (b) PA programming; and (c) eating patterns (see Table 3). An inductive approach was used to identify patterns or commonalities that characterized the perceptions of the women who participated in the semistructured interviews. In order to ensure transferability of the data, sufficient information was provided regarding research context, research processes, research participants, and research participant relationships to enable the reader to decide how findings may transfer.

4. Data Analysis

- All interviews were audio taped. Tapes were reviewed and transcribed verbatim immediately after the semistructured interviews. AtlasTi (Scientific Software Development; Berlin) software was used for data management. Inductive analysis was performed on the data. The data were categorized into themes that emerged from the questions. Procedures for grounded theory data analysis include open, axial, and selective coding. Open coding includes an examination of the text for common categories and themes. Once these categories were developed, the data were examined again to determine smaller categories that emerged from the larger categories. This process continued until the data were completely “saturated” (Creswell, 2002). Data saturation is a term used when no new information seems to emerge during coding and when no new properties,dimensions, conditions, actions/interactions, or consequences are seen in the data. Axial coding took the categories developed during open coding and generated relationships among the categories.The third step was selective coding. This process entailed selecting the core categories, validating the relationships, ensuring that all data were accounted for, and ending with a core or central category[9]. In order to ensure confirmability, Dr. Jason Crandall analysed all data. At the same time, another investigator of equal qualitative research experience, Dr. Justine Reel, also analysed the data. Consensus was reached on data analysis to ensure correct coding of themes, data saturation, and consistent identification of the relationships of categories.

5. Participant Profiles

- The ages, educational levels, and life experiences of the participants were varied. Pam was a 22-year-old junior university student majoring in exercise science. As an adolescent, she was reminded by her mother that “she was becoming a woman” and “couldn’t eat after school” as she had done as a young child. Sherry was a 60-year-old local community college professor with master’s degrees in both business management and business communications. She reported struggling with chronic fatigue syndrome and had recently reduced her body weight from 202 lbs to 160 lbs. Jamie was a 57-year-old collections manager. She completed 2 years of college and was currently a member of a weight management group. She also struggled with depression and openly discussed her problem with compulsive overeating. Melissa was a 42-year-old university office specialist who had completed an associate’s degree in communications and was 1 year away from completing her bachelor’s degree in the same area. She was a member of a weight management group. Melissa described feelings of guilt for being physically active. Her guilt was a result of not spending time with her family. Karen was a 28-year-old university security guard who was one credit short of graduating from high school. She lost her mother at the age of 18, which resulted in her battle with depression and heroin. At the time of the interview, she claimed to be free of her heroin addiction but still struggled with depression.

6. Results

- Semistructured interview questions were constructed around three general areas: (a) PA perceptions; (b) PA programming perceptions; and (c) eating patterns. The patterns and commonalities for each general area are presented in the following sections, along with more detailed descriptions of participant responses for each general area.

7. Physical Activity Perceptions

- It was important to understand the participants’ experiences with PA throughout their life spans. First, participants were asked to define PA because it was important to determine if they believed there were differences between structured and unstructured activities. Second, questions were designed to determine past and current experiences with PA, including specific physical activities in which they participated and reasons for decreases in PA during certain periods of their lives.When the participants were asked to define PA, they all agreed that PA involved; (a) any type of movement performed for a period of time; (b) using muscles; and (c) any type of movement at least as strenuous as walking. However, the types of activities included and the effects of these activities varied greatly among participants. Jamie, Karen, Pam, and Sherry agreed that PAs included exercise but that PA was more fun than exercise. Jamie, Karen, and Pam listed activities such as skiing, soccer, and softball as PAs. These activities were fun and did not require them to think about what they were doing. Melissa initially defined PA and exercise the same. Later she described exercise as “anything that gets you sweaty, makes you feel sleepy, and she is boring[but it is useful for] taking the weight off” as compared to PA that does not take the weight off.

8. Physical Activity Programming Perceptions

- In order to design a more optimal PA program for BED individuals, questions were asked to determine the participants’ perceptions of PA programs, including perceived benefits of and perceived barriers to PA, the type of environment in which they would feel most comfortable being physically active, and the type of PAs they would most enjoy if they began to be physically active.All of the participants, with the exception of Sherry, expressed a positive attitude towards PA by describing positive effects of participation. Karen believed that being physically active could relieve her frustrations. Jamie listed more physical effects such as better health, lower weight and cholesterol, and increased high-density lipoproteins. Melissa, Pam, and Karen believed that PA could provide more psychological benefits such as having a better self-image, relieving stress, and providing confidence.The participants listed past and current perceived barriers to PA. All of the participants reported being physically active childhood and adolescence. Structured PAs included softball, drill team, and soccer. Unstructured activities were discussed more often than structured activities and included roller-skating, dodge ball, swimming, and kickball. However, between high school and young adulthood, their PA levels decreased. The reasons for these reductions varied among participants. Sherry was physically active as a child but stopped enjoying it when she was forced to participate in physical education class during high school. Her enjoyment stopped because she felt clumsy in front of the class. In college, she was discouraged from participating in sports because there was a possibility her “hymen would be broken” from her participation. Melissa was physically active until the age of 28 when she married, began to work, and chose to take care of her family. Pam reported a similar progression from being physically active to physically inactive. Until high school, she reported participating in many structured activities such as skiing and soccer. After high school, PA was not part of her schedule, and participation was more difficult. Jamie rode horses and played soccer until her late 20s when she was divorced. During her post divorce period, she was prescribed antidepressant medication, which reduced her motivation to be physically active. Body weight was seen as limiting her ability to execute movements or engage in strenuous activities. Jamie said, “I’d like to be able to hike even more, but I have a problem with elevation. I think that it has a lot to do with my weight.” The types of PAs preferred by the participants were related to the types of physical environment in which they felt most comfortable. Most of the participants would rather be physically active outside of the exercise facility or health club setting. This setting made them uncomfortable because the people were obnoxious, put them down, and stared. The interviewees in the current study did not want to exercise alone regardless of the PA environment. Melissa liked to walk with her husband but felt she had to choose between being physically active and caring for her family. She felt guilty choosing PA. Sherry preferred to walk with her husband or daughter. However, chronic fatigue syndrome diminished her capacity for PA. Karen preferred to play softball but was hindered by her chronic asthma. Jamie liked to exercise outdoors but could not due to her allergies.

9. Eating Patterns

- In order to determine how PA affected the eating patterns of the participants, questions were designed to probe eating patterns/history and the possible relationship to PA participation. In addition, questions were designed to determine more about emotions leading to binge eating episodes as well as the possible feelings and effects, both negative and positive, of adding PA to the participants’ lifestyles. Sweets and sugar addiction were mentioned by all of the participants. Pam told how she always loved candy. Sherry’s earliest memories were tubs filled with Coke and orange soda. Sherry described her physical state after episodes of eating large amounts of sugar as a sugar coma. Karen described her sugar addiction.I mean I splurge. I eat a whole bunch of candy and then the next night I’ll eat a whole bunch of candy. Sometimes I’ll get up in the middle of night and not even know it and start eating. . . . I love candy. I love cherry candy, love it. . . . I’ll eat cherry taffy that’s about this big, then a Skor, almond chocolate bar and little rascal things that are about this big. Then[I’ll eat] a pack of Skittles that are supposed to be gum but I chew and swallow.The participants described emotions that both triggered binge eating episodes and were the result of binge eating episodes. All of the participants described food as a coping mechanism. Sherry and Karen identified depression as triggers for their episodes, whereas Pam would binge eat in response to anxiety about her life. Jamie, Karen, and Pam described a relationship between their mothers and binge eating. For Jamie and Pam, binge eating was a way to fix what they were not getting from their mothers. For Karen, binge eating began after her mother’s death and the ensuing depression. Melissa began binge eating and purging in high school because all of her friends looked like Twiggy, and she felt that she needed to maintain a certain body weight. She stopped purging when, during a particular episode, she could not breathe. From that point, she did not purge but continued to binge. In addition, although caloric intake andmacronutrient composition were not measured during this study, it is possible that the poor food choices, including those high in refined sugar, could hinder participation in PA due to low energy levels. The binge eating affected the levels of PA for all of the participants, except for Jamie who did not see a relationship between her binge eating episodes and PA. Karen said, “After I ate all of that, I wake up still full and don’t feel like doing anything.” Melissa, Sherry, and Pam described a similar feeling that was somewhat analogous to the feeling one gets after Thanksgiving dinner. They did not believe they could be physically active after these types of binge eating episodes.The participants believed that PA could positively affect their binge eating. Pam believed that on days she was physically active she ate more normal. Sherry believed that PA could decrease her binge eating because it would make her feel better emotionally. Conversely, Melissa had a ravishing appetite after exercise. She would eat more after being physically active. Karen had similar feelings, believing that after being physically active she needed to replace the energy she had used. In summary, PA was any activity that involved movement performed for a period of time, used muscles, and movement at least as strenuous as walking. PA was fun and included activities such as softball, skiing, and snowboarding. Exercise was considered boring and made them sweaty but was useful for weight loss. Participants believed PA was a positive behavior.Perceived benefits included improved psyche, removal of frustrations, increased stamina, and improved confidence and physical health such as increased high-density lipoproteins. The participants listed perceived barriers to PA such as body weight, allergies, physical pain and injuries, work schedules, time constraints, family priority over self, compulsive issues (cleanliness), chronic fatigue, and social physique anxiety or fear of being observed in public. All of the participants were all physically active as children, but reported reduced PA between high school and young adulthood.All of the participants suggested some link or special craving related to sweets and sugar. They described eating in response to emotions and a tendency to eat at night. Comments from significant others, including their mothers, influenced their eating. Binge eating resulted in decreased PA due to uncomfortable physical sensations.

10. Discussions

|

- The purpose of this study was to more fully explore and examine issues related to PA adherence in BED participants. More specifically, Crandall and colleagues conducted semistructured interviews to explain more fully findings from an earlier study of the relationship between BED and PA, with the ultimate goal of gaining insight for designing a more effective PA intervention for BED participants[2]. The participants’ perceptions of PA were elucidated during the semistructured interviews. Their perceptions were important to ascertain because BED participants’ knowledge and attitudes toward PA were unknown. When asked to define PA, the participants described PA as fun activities that did not require a great deal of effort, but were not capable of producing significant weight loss. Exercise was defined as strenuous activities that made one sweat and were useful for weight loss. The participants did not understand the role that unstructured or unplanned PA could play in increasing their overall health. The BED participants from our original study revealed that as they grew older lifestyle activities began to predominate. For example, as young adults, activities were more structured such as aerobic dancing, softball, jogging, and swimming. As mature adults, the top three activities were walking, hiking, and gardening. Although participating in these types of lifestyle activities, the participants did not recognize their value. As the participants grew older, their barriers to PA began to increase. As a result, structured PA was reduced and lifestyle activities increased because they were easier to access and perform. However, all of the participants believed that compared to structured activities lifestyle activities were not useful for reducing body weight. Body weight was mentioned by all of the interview participants as limiting their ability to execute movements or engage in strenuous activities. Given these findings, there is a need to educate BED individuals as to the definition of PA and the benefits of structured and unstructured PAs. These benefits include improvements in physiological variables such as reductions in chronic disease risks and improvements in the psychological factors the participants described in detail such as improved confidence and improved psyche. When the perceived barriers from our initial study were combined with the barriers described by the semistructured interview participants, the following overall barriers emerged. Personal barriers included (a) social physique anxiety (clothes made them look funny); (b) health problems (allergies, physical pain, chronic fatigue, and injuries); (c) compulsive issues (cleanliness); and (d) lack of fitness (excess body weight). Environmental barriers included (a) lack of time (work schedules); (b) social barriers (family priority over self); and (c) access (exercise programs cost too much, there were too few places to exercise, and facilities’ schedules were inconvenient). Table 4 presents a cross-case analysis of these perceived barriers.

11. Personal Barriers

- Barrier efficacy is the confidence to overcome possible barriers that interfere with regular PA participation and seems to be a critical predictor of participation[10]. A majority of the personal barriers reported by the participants were related to their feelings in an exercise environment. A structured exercise setting such as an exercise facility made them feel self-conscious because they were uncomfortable being observed in exercise clothes. These feelings may have been related to their excess body weights since they felt their current body weights affected their self-efficacy to perform PA. These thoughts could be indicative of social physique anxiety. Social physique anxiety is the degree to which individuals become anxious when others observe their bodies[11]. Social physique anxiety could severely limit the effectiveness of any structured exercise program for BED participants. By creatively addressing the environmental barriers listed by the BED participants, it may be possible to reduce or eliminate social physique anxiety and at the same time address other pertinent personal factors related to exercise adherence.

12. Environmental Barriers

- In order to fully address the environmental barriers related to poor PA adoption and maintenance, a paradigm shift is needed. Traditional exercise program activities are often limited to structured exercise settings such as fitness centers and health clubs. The perceived barriers listed by the BED participants could be addressed by simply designing a program based on more unstructured and fun lifestyle activities. Ransdell and colleagues designed a home-based intervention that significantly reduced perceived barriers to exercise and improved health-related fitness variables such as blood pressure and aerobic capacity[12]. Unstructured PAs were included in the intervention such as walking with significant others, taking the stairs instead of the elevator, and gardening. Many of the participants in the current study felt guilty taking time to exercise because it took time away from their families. Incorporating activities involving family would allow family time and increase PA.More structured activities (e.g., church league softball, skiing, hiking, and strength training) could be used, but an emphasis should be placed on making the activities more enjoyable for the participants because many of them mentioned fun as an important programming component. These activities could be performed outside of an exercise facility, thus eliminating the anxiety associated with exercise clothes and the individuals at the facility who made them feel uncomfortable. Because these activities could be performed at relatively low intensities, those with health problems would have little trouble accomplishing them. Time constraints, listed as one of the most common perceived barriers to PA in both sedentary and active individuals, could be reduced because the participants could perform many of the activities while doing other daily activities. Exercise facility equipment, because of its high usage, will become soiled by perspiration. BED participants expressed concern for the cleanliness of these types of facilities. Unstructured activities could address this perceived barrier. Home-based exercise programs could also be prescribed to eliminate the lack of the cleanliness barrier.Because most exercise professionals work within an exercise facility, it may sometimes be difficult to prescribe unstructured PAs that are performed outside of the exercise facility. Therefore, it may be necessary to modify the environment of the facility to decrease or eliminate the perceived barriers to exercise. Addressing the barriers discussed by the BED participants would increase the probability of a more successful intervention. Limitations were found to this study. Due to time constraints, the semistructured interviews were limited to 5 BED participants. A larger sample may have revealed different perceived barriers and further elucidated the findings of this study. A deductive approach was used for construction of the interview guide. This format may have limited responses by the BED participants. Specific steps normally taken in qualitative methodology were not included in this study. These steps included peer debriefing, member checking, reflexive journal, audit trail, and triangulation. Future research may utilize a more inductive approach for the semistructured interviews and increase the sample size.

13. Conclusions

- The objective of this study was to apply qualitative research methodologies to enrich our understanding of the quantitative data gathered by Crandall and Colleagues describing PA within the lives of BED individuals[2]. Barriers perceived by BED participants and possible ways to address them have been discussed. To successfully address these barriers, it may be necessary to shift the current exercise paradigm that is focused on structured exercise programs. Structured exercise is planned exercise and most often associated with health clubs and fitness centers. Choices for exercise are often limited to activities contained within this setting. These types of programs have and will continue to be successful at targeting specific populations. Unfortunately, these programs may not be the best approach for BED individuals. Shifting to a paradigm that emphasizes unstructured home-based and family-oriented PAs and includes some enjoyable structured activities may increase adherence levels in BED populations. A treatment approach utilizing behavioural therapies, nutrition education, moderate caloric restriction, and moderate physical activity may decrease binge eating episodes and may promote weight loss in obese binge eaters. This study confirms that if perceived barriers are adequately addressed BED participants are more likely to participate in physical activity. However, the psychopathology associated with this disorder such as depression, compulsive behavioral tendencies, and low self-esteem will challenge the programming skills of PA professionals.

References

| [1] | Grilo, C.M., White, M.A., & Masheb, R.E. (2009). DSM-IV Psychiatric comorbidity and its correlates in binge eating disorder. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 42, 228-234. |

| [2] | Crandall, K. J., Eisenman, P. A., Ransdell, L. B., & Reel, J. R. (2011). Exploring binge eating and physical activity in community-dwelling women. International Journal of Psychology and Behavioral Sciences, 1(1): 1-8. |

| [3] | Brownley, K.A., Berkman, N.D., Sedway, J.A., Lohr, K.N., & Bulik, C.M. Binge Eating Disorder: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. (2007). International Journal of Eating Disorders, 40, 337-348. |

| [4] | Wonderlich, S.A., Gordon, K.H., Mitchell, J.E., Crosby, R.D., & Engel, S.G. (2009). The validity and clinical utility of binge eating disorder. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 42, 687-705. |

| [5] | Hausenblaus, H. A., Cook, B. J., & Chittester, N. I. (2008). Can exercise treat eating disorders? Exercise and Sport Science Reviews, 36 (1): 43-47. |

| [6] | Levine, M.D. & Marcus, M.D. (2003). Psychosocial treatment of binge eating disorder: An update. Eating Disorders Review, 14, 3. |

| [7] | Pendleton, V. R., Goodrick, G. K., Poston, W. S. C., Reeves, R. S., & Foreyt, J. P. (2002). Exercise augments the effects of cognitive-behavioral therapy in the treatment of binge eating disorder. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 31, 172-184. |

| [8] | Sechrist, K. R., Walker, S. N., & Pender, N. J. (1987). Development and psychometric evaluation of the exercise benefits/barriers scale. Research in Nursing and Health, 10, 357-365. |

| [9] | Creswell, J. W. (2002). Educational research: Planning, conducting, and evaluating quantitative and qualitative research. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Pearson Education. |

| [10] | Rhodes, R. E. & Nigg, C.R. (2011). Advancing physical activity theory: A review and future directions. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 39, 113-119. |

| [11] | Ransdell, L. B., Wells, C. L., Manore, M. M., Swan, P. D., & Corbin, C. B. (1998). Social physique anxiety in postmenopausal women. Journal of Women and Aging, 10(3), 19-39. |

| [12] | Ransdell, L. B., Taylor, A., Oakland, D., Schmidt, J., Moyer-Mileur, L., & Shultz, B. (2003). Daughters and mothers exercising together: Effects of home- and community-based programs. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 35, 286-296. |

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-Text HTML

Full-Text HTML