-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Food Science and Nutrition Engineering

p-ISSN: 2166-5168 e-ISSN: 2166-5192

2019; 9(1): 1-15

doi:10.5923/j.food.20190901.01

Analyzing the Tragedy of Illegal Fishing on the West African Coastal Region

E. C. Merem1, Y. Twumasi2, J. Wesley1, M. Alsarari1, S. Fageir1, M. Crisler1, C. Romorno1, D. Olagbegi1, A. Hines3, G. S. Ochai4, E. Nwagboso5, S. Leggett6, D. Foster1, V. Purry1, J. Washington1

1Department of Urban and Regional Planning, Jackson State University, Jackson, MS, USA

2Department of Urban Forestry and Natural Resources, Southern University, Baton Rouge, LA, USA

3Department of Public Policy and Administration, Jackson State University, Capitol Center Jackson, MS, USA

4African Development Bank, AfDB, Avenue Joseph Anoma, Abidjan, Ivory Coast

5Department of Political Science, Jackson State University, Jackson, MS, USA

6Department of Behavioral and Environmental Health, Jackson State University, Jackson, MS, USA

Correspondence to: E. C. Merem, Department of Urban and Regional Planning, Jackson State University, Jackson, MS, USA.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2019 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

The West African coastal region has long been regarded as one of the most fertile fishing regions in the globe. For that, in many of the region’s coastal communities, fishery stands out as a vital component of the surrounding ecosystem central to economic activities among citizens. However, recurrent overfishing by illegal foreign vessels is not only impeding sources of revenue and food security in the area. During the last several years, the widespread plunder of local fisheries by foreign trawlers engaged in illegal fishing continues unabated with indelible marks on communities. Considering the implications, the ongoing fishery crisis which has now reached monumental proportions is fast becoming a regional tragedy which must be dealt with it, if not, prosperity in West Africa could be elusive. While this comes at the expense of locals whose coastal waters are repeatedly encroached upon by illegal foreign trawlers. Such activities trigger depletion and biodiversity disappearance, loss of income and exposure to poverty due to many elements such as weak institutions, ineffective laws, absence of regional action plan and size of the West African fishing zone. Notwithstanding the lingering dilemmas, the fascination of mainstream literature all those years focused solely on fishery crisis elsewhere with little on West Africa. Thus, this paper will fill that void by examining the tragedy of over fishing using a mix scale approach of descriptive statistics and GIS with emphasis on the issues, trends, factors and impacts. From the temporal-spatial analysis, the result shows vast potentials based on the output as well as growing depletion, losses from illegal activities and impacts prompted by a host of socio-economic and physical factors. The paper offered solutions ranging from the promulgation of stricter regulations, legal actions by West Africa, the repatriation of funds, regional cooperation and effective monitoring.

Keywords: Fishery crisis, West African coast, Plunder, Illegal fishing, Foreign trawlers, Impacts, Depletion

Cite this paper: E. C. Merem, Y. Twumasi, J. Wesley, M. Alsarari, S. Fageir, M. Crisler, C. Romorno, D. Olagbegi, A. Hines, G. S. Ochai, E. Nwagboso, S. Leggett, D. Foster, V. Purry, J. Washington, Analyzing the Tragedy of Illegal Fishing on the West African Coastal Region, International Journal of Food Science and Nutrition Engineering, Vol. 9 No. 1, 2019, pp. 1-15. doi: 10.5923/j.food.20190901.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- The West African coastal region has long been regarded as one of the most diverse and fiscally significant, fertile fishing regions in the globe facing the highest levels of illegal, unreported or unregulated (IUU) fishing activities [1-3]. Yet, in many of the region’s coastal communities, fishery stands out as a vital component of the economy and ecosystem central to the daily lives of citizens [4-12, 2]. However, the recurrent overfishing by illegal foreign vessels is not only impeding sources of revenues and food security in the area [13], but in the last several years, the plunder of local fisheries by overseas trawlers has continued unabated to the extent that decades of intense exploitation has resulted in the overfishing of over 50% of fisheries stocks in West African waters [14-16]. By and large, the global aspects of the crisis cannot be ignored, since the fishery depletion that struck communities decades ago continues to reverberate in some areas [17]. Even at that, hundreds of illegal fishing vessels enter African waters and trawl daily for shrimp, sardines, tuna, and mackerel worth $1 bn annually in an overfished environment [7, 18, 19]. In the process most, IUU vessels off the West African coast stay in operation 365 days [20-22], putting massive pressure on the region’s fish stocks [23-26]. The refrigerated ships linked to these operations then head to ports in nations with lax controls, where they off load their catches [27]. The practice of using a flag of convenience (FOC) also makes it easier to engage in IUU fishing activity [28].Given the declining pace of fish stocks from these operations, considerable damage has already been done, and as a result, West Africa’s fish assets have been declining rapidly, both because of trawling and unregulated and excessive fishing by locals and legal commercial fleets [29-33]. For that, many fishery stocks in the West African region have already collapsed and others will gradually follow, and some have been on the decline since the 1980s [34-37]. It is estimated that around 40% of all fish caught in West African waters occurred illegally by fishers from abroad [38, 39, 36]. The problem is further compounded by the lack of efficient fisheries management systems and the weak institutions in West Africa that allow firms exploit marine resources at a low cost [40, 41]. These companies come from all over the world; from Japan, South Korea, Russia, Spain, France, Italy and China and others [42]. On top of such unsustainable practices, West African countries have done very little to address the challenges. [41]. As a result, overfishing and illegal activities by foreign vessels are driving many species towards extinction and destroying the livelihoods of fishing communities in countries of the region [43]. From 1950 to 2009, over 250 species of fish landings were reported taken by coastal and 47 DWF nations. Furthermore, the overall nominal catches soared 12 times from 300,000-3,600,000 MT during that period [42]. In view of the implications, if not properly dealt with by the countries, the current plans for economic prosperity in West Africa could be elusive [44]. These acts trigger fishery resource depletion and biodiversity disappearance, loss of income and exposure to poverty due to many elements such as the absence of effective legislations, weak institutions [45, 46], the lack of a regional action plan to curb the activities of illegal foreign vessels and the size of the West African fishing zone.Aside from the socio-ecological costs of illegal trawling [11]. The fascination of mainstream literature centred only on the crisis of the Eastern Atlantic sea board in North America during the 1990s [47, 48] with little on West African coastal waters. Added to that, there is strong evidence to suggest that, most illegally harvested fish originate from the coasts of developing countries and transported for sale in the west [10]. As a result, when a country imports fish, it is nearly impossible to know if the fish was legally acquired. It is believed that some portions of all fish imports involve illicit stock, from West Africa. In that way, billions of dollars in illegal fish imported into the EU every year come from West Africa. Given the limited coverage of these issues, this paper will fill that void in research by examining the tragedy of over fishing in West Africa using a mix scale approach of GIS and descriptive statistics [49-52]. Emphases are on the issues, trends, factors, and impacts. The paper has five objectives. The first aim involves the use of spatial technology to assess the effects of illegal fishing, while the second is to create a support device for policy makers. The third aim strives to develop a mitigation strategy. The fourth objective is to design a structure for effective coastal fishery management and the fifth objective is to identify exposures to depletion. The study is organized in four sections beginning with introduction and methods in parts 1 and 2 coupled with the results and discussions in parts 3 to 4 followed by the closure in part 5.

|

2. Methods and Materials

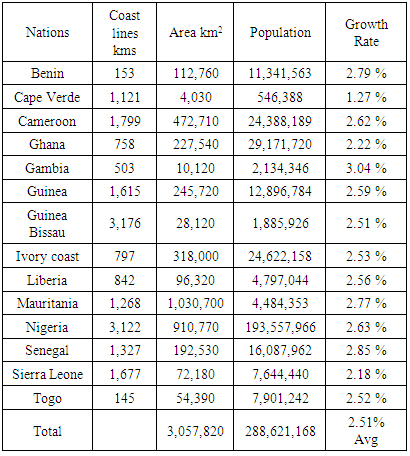

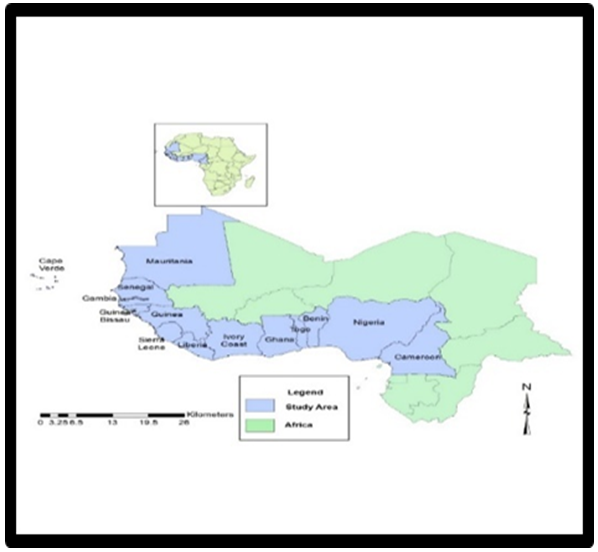

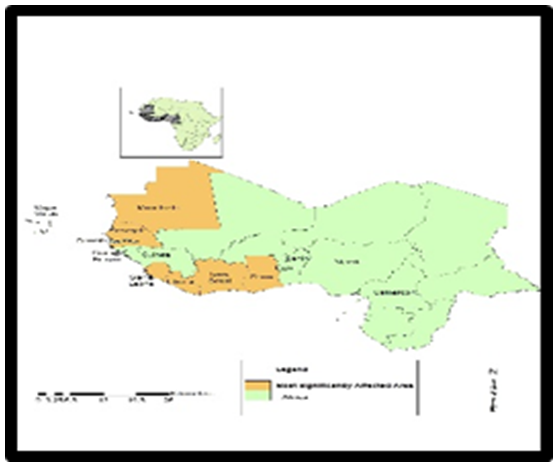

- The region (Figure 1) stretches through a 3,057,820 km2 area across 14 nations in West African coastal zone from Senegal in the west to Nigeria in the south. With a population of 288 million and average growth of 2.00% [53], and some of that in coastal areas where millions depend on the fishing sector for their daily livelihood. The region has also a vast tapestry of mangroves and estuaries on a 18,303 km2 coast line and a maritime Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) of 2,016,900 km2, off the Atlantic Ocean with abundant fish stocks [54, 55]. Added to that, the region’s coastal waters include some of the world’s most abundant fishing grounds [56] serving commercial vessels, local fishers and the markets in Asia. From the 000,000 of tons in yearly output in the early 1960s, fisheries production in countries belonging to the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) is now estimated at over 2 million tonnes, or 3.5 percent of world production [42]. The profits generated are not only substantial, but the coastline of West Africa contains some of the world’s most assorted and rich fisheries, currently besieged by depletion due to overfishing in the East Central Atlantic fishing zone [57, 58]. Based on regional data overfishing most significantly affects the nations [10, 11], such that people from Senegal to Nigeria bear the daily brunt of loss of livelihoods [10, 11]. Even though overexploitation of West Africa’s fishery resources has produced devastating social, economic impacts, income sources of artisanal fishers are being destroyed, a vital provider of protein is being lost, and opportunities for the development of regional production and trade are disappearing by the continued escalation of IUU fishing activities.

| Figure 1. The Study Area West Africa |

2.1. Methods Used

- The paper uses a mix scale approach of descriptive statistics and secondary data connected to GIS to assess the illegal fishing activities by foreign trawlers off the coast of West Africa. The spatial information for the enquiry was obtained from several agencies consisting of the World Bank group, the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) and the United Nations Economic Commission For Africa (UNECA). Other sources of spatial info emanate from the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), the United Nations Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO), the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and the African Union. In addition to that, the Government of the United Kingdom, The United Nations Environment Program (UNEP), the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), EU Ministry of Maritime Affairs and Fisheries also provided other information needed in the research. Generally, the bulk of fishery stock indicators relevant to the region and individual nations were obtained from the Nigerian Bureau of Statistics, The national archives from Ghana, Senegal to Nigeria, the Nigerian Federal Department of Fisheries (FDF) and The Federal Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development for some of the periods.Since the regional and federal geographic identifier codes of the nations were used to geo-code the info contained in the data sets. This data was processed and analyzed with basic descriptive statistics, and GIS with attention to the temporal-spatial trends at the national, state and regional levels in the West African coastal region. The relevant procedures consist of two stages listed below.

2.2. Stage 1: Identification of Variables, Data Gathering and Study Design

- The initial step in this research involved the identification of variables required to analyse the extent of harvest or production and changes at the national level from 1980 to 2015. The variables consist of socio-economic and environmental information, the total size, the averages and percentage of fish stocks, marine and inland sources, marine capture from fishing areas and the percentage change. The others consist of variations, amount or capacity of fish carried by reefers, number of trips, frozen fish cargo capacity, the amount of catch and number of vessels, the monetary values in $, the number of source nations, the number of vessels, the frequency of fishing violations. Added to that are the loss induced by IUU and the total, the percentage of IUU, tonnage of IUU and monetary cost of lost opportunities in $. These variables as mentioned earlier were derived from secondary sources made up of government documents, newsletters and other documents from NGOs. This process was followed by the design of data matrices for socio-economic and environmental variables covering the periods from 1980, 2003 to 2008 to 2015. The design of spatial data for the GIS analysis required the delineation of county boundary lines within the study area as well. Given that the official boundary lines between the 14 countries remained the same, a common geographic identifier code was assigned to each of the area units for analytical coherency.

2.3. Stage 2: Data Analysis and GIS Mapping

- In the second stage, descriptive statistics and spatial analysis were employed to transform the original socio-economic and ecological data into relative measures (percentages, ratios and rates). This process generated the parameters for establishing, the extent of fishery losses and production, violations and other issues induced by over fishing across the region for each of the countries through measurement and comparisons overtime. While the spatial units of analysis consist of countries, region and the boundary and locations where illegal fishing operations and over fishing thrived, this approach allows the detection of change, while the graphics highlight the actual frequency and impacts, fishery stock losses and the intensity of operations and the trends as well as the economic costs. The remaining steps involve spatial analysis and output (maps-tables-text) covering the study period, using Arc GIS 10.4. and SPSS 20.0. With spatial units of analysis covered in 14 countries (Figure 1), the study area map indicates boundary limits of the units and their geographic locations. The outputs for each country were not only mapped and compared across time, but the geographic data for the units which covered boundaries, also includes ecological data of land cover files and paper and digital maps from 1980-2015. This process helped show the spatial evolution of various activities, the ensuing impacts, as well as changes in other variables and factors driving overfishing in the study area.

3. The Results

- This segment of the enquiry focuses on temporal and spatial analysis of fishery crisis in the study area. There is a starting focus on the analysis of fish production. The other parts delve on illegal operations and the forms coupled with fishery losses off the coast of West Africa using descriptive statistics. This is followed by the remaining portions of the section comprising of impacts, GIS mappings, and the identification the factors behind unauthorized fishing off the West African coast.

3.1. Fish Production in West Africa 1980-2015

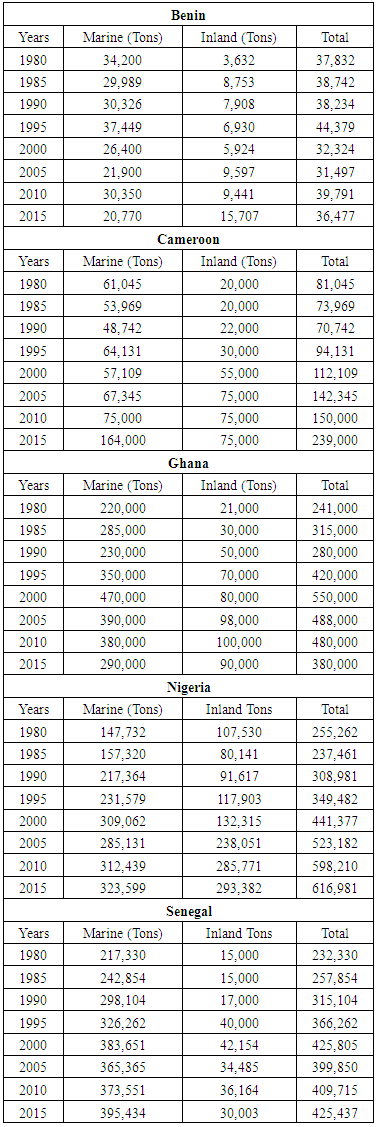

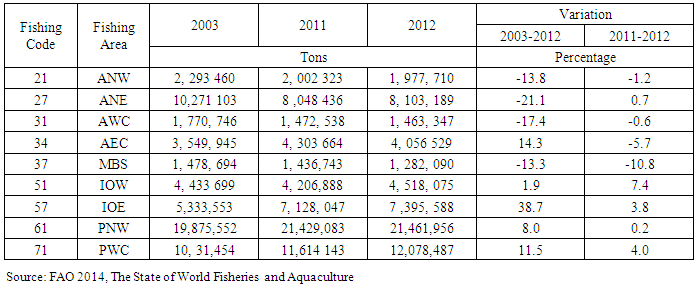

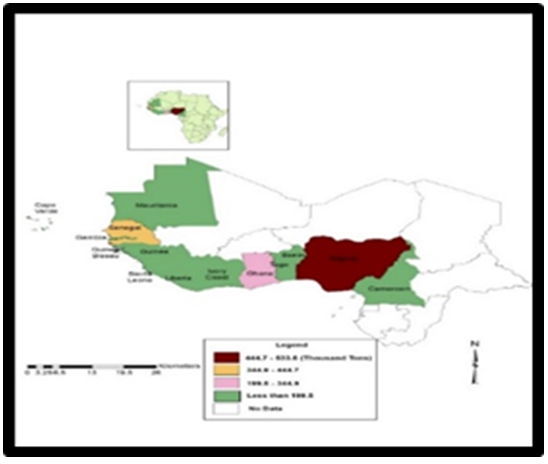

- Fish production trends among the countries of the region from 1980 to 2015 are covered under three categories. The output levels at that time consists of those listed as marine, inland and the total quantities. Since much of the fish that were caught during the timeframe among the nations of the study area came mostly from marine zones and inland areas, there exists a disparity pattern among the two sources. Given the disproportion between marine and inland fish production in Benin republic over the years. The total output fluctuated by 37,827 to 38,000 tons between 1980 to 1985, while 1995 accounted for the highest volumes of production estimated at 44,379 tons. In the other years (2010-2015), total production for the country fell from 39,791 tons to 36,477 tons. In Cameroon where the total fish production levels varied in the tens of thousand tons (81,045 to 94,113) all through 1980 to 1995. During the 2000s, production levels rose by the hundreds of thousands (112,109 to 239,000 tons). Elsewhere, the situation in Ghana shows an interesting scenario as increments of 241,100-315,000 tons in production between 1980 through 1985 highlight the extent of pressures from fishing activities during the early years in the country. By 1991 to 1995, the fish output in Ghana dropped from 280,000 to 420,220 tons and from then onto 2000-2010, the overall fish production in the country drastically plummeted yearly from 550,000 to 380,000 tons. Among the two biggest fish producers as shown on the table, Nigeria’s total fish production stayed on the rise much of the time from 1980-2015 except for 1980-1985 when production went from 255,262 to 237,461 tons. In the other periods, Nigeria’s fish production volume rose by 308,981 to 341,482 tons and 598,210 to 616,981 tons during 1990-1995 and 2010-2015 respectively. In the case of Senegal, fish production there also grew in the same periods on a back to back basis beginning with the 232,330 to 257,854 tons and by 409,715 to 425,437 tons (Table 2).

|

|

3.1.1. Fish Production along the Major Fishing Zones

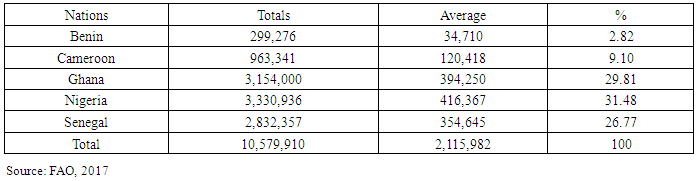

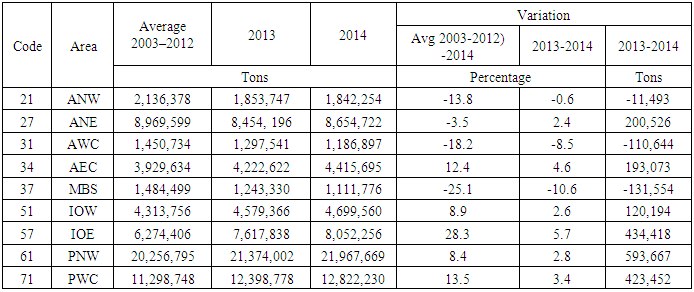

- Understanding production trends over the years through marine capture along the major fishing areas requires a delineation of the fishing area codes as listed on the tables 4-5. Even though the fishing area codes range from 21 to 71 under fishing areas spanning from the Atlantic North West (ANW) to the Pacific Western Central (PWC), the activities in the study area of interest falls under fishing area number 34 dubbed the Atlantic Eastern Central (AEC). From the activities along the marine zones, the information on table 2 highlights the mounting evidence of marine fishing involving millions of tons beginning from 2003, 2011 and 2012, and the variation levels over time. Seeing how fish production in the west African zone fluctuated, the activities in the AEC fishing area may have to do with it. As a zone that covers the study area, during 2003-2011 and 2012, the amount of fish caught in the zone went from 3,549,945 to -4,303,664 but only to drop by 4,056,529 million tons. The varying percentage rates of 14.3 to -5.7 for 2003-2012 and 2011-2011 reflects the extent of gains and declines in terms of fish catches in the area. Such level of deficits raises serious concerns on future productive capacity and the ability to harvest fishery stocks in the face of depletion between 2011 to 2012 (Table 4). In other years, the Atlantic Eastern Central fishing area had an average of 3,929,634 million tons in 2003-2012 in marine capture production. By 2013 and 2014, production average rose from 4,222,622 to 4,415,695 million tons. With no visible deficits during these periods, the percentage for the average and the variations for the Atlantic Eastern Central zone were in the order of 12.4 to 4.6% coupled with gains of 193,073 tons from 2013 to 2014. Notwithstanding, the trends in the zone, in comparison to the broad undertakings pertaining to fish stocks, there are reasons to worry in the East Central Atlantic fishing zone. Consequently, for quite some time now, about 53% of the stocks in this region remain over fished (Table 5). See Appendix 1 for full meanings of the fishing zones acronyms listed on Table 4 and 5.

|

|

3.1.2. Illegal Operations and the Forms in the Region

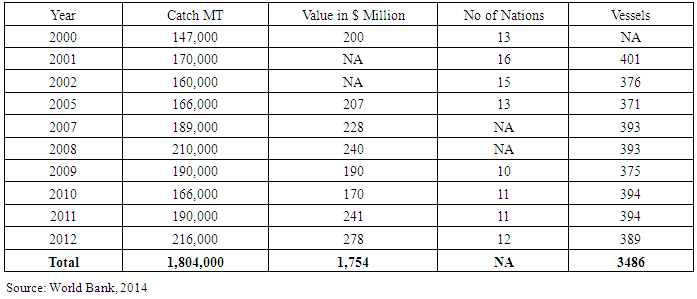

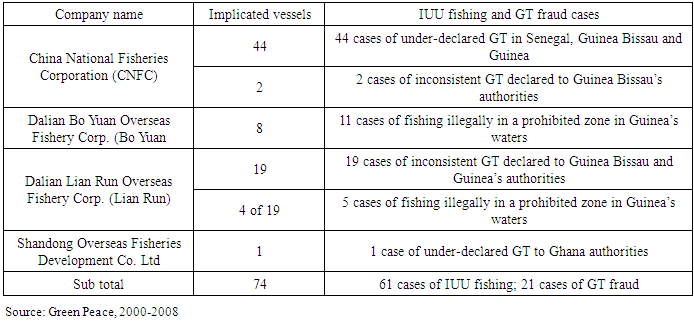

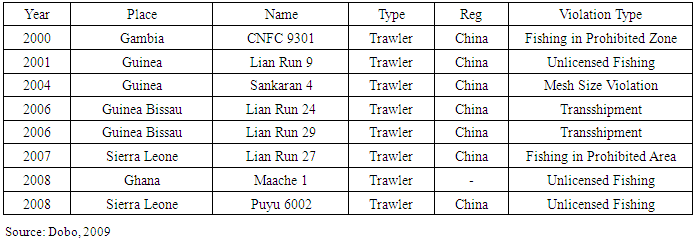

- Of the different forms of illegal fishing off the coast of West Africa, one need not lose sight of the activities of reefers, the import hubs of stolen frozen fish from the region alongside the containerized frozen fish sites that are critical in the long run. Seeing the frequent daily operations off the West African coast and the samples from 9 illegal reefers. In 2013, reefers operating in the area with flags of convenience of various nationalities, hurled in about 26,459.64 MT in 19 trips. Being a place where frozen fish from the West African coast enters Europe, the Las Palmas port in 2016 logged in 349 trips from ships carrying 118,701 MT of fish. Another twist to the illegalities stems from the involvement of China. The officially reported fish catches by Chinese operators on the waters of many countries in the West African region from 2000 to 2012 point to 1,804,000 MT, at an average of 180,400. This involved activities of relative intensity at three different periods. The volume of fish catches in the West African region involving trawlers stood at 100,000 MT plus levels all these years. Thus, in the periods 2008 and 2012, Chinese operators hurled in over 200,000 MT than the other years. Over the years (2001-2007 and 2011), the second most notable activities in the volume of marine catches consisted of 170,000, 189,000 -190,000 MT tons coupled with 160,000-166,000 for 2002 through 2010. At a total of $1,754 billion dollars in monetary value during 2000-2012, these fishing operations relied on hundreds of vast fleets of trawlers on the high seas of many countries of the West African region. In a region of about 14 countries, the immense penetration of 13 to 16 trawlers in almost all of them from 2000 to 2005 reaffirms the growing scales of fishing activities in the region. Even though the sphere of fishing operations based on official Chinese records dropped from 10 to 12 by 2009 through 2012, the amount of fish catches estimated at hundreds of thousands of MTs and numerous fleets of vessels deployed, showed the intensity in the West African region (Table 6). From the frequency of the violations between 2000 and 2014, about 74 vessels were implicated while the IUU fishing and fraud cases involved were reported in various countries of the region from Senegal, Guinea Bissau and Ghana (Table 7).

|

|

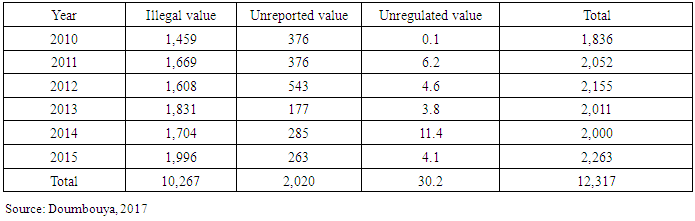

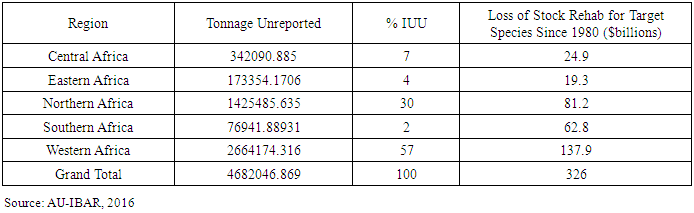

3.1.3. Fishery Looses from Illegal Activities

- The monetary equivalent of fishery loses by unauthorized activities off the West African coast has been on the rise over the years. With the unauthorized activities highlighted under different categories to that effect, between 2010 through 2015, IUU fishing in West Africa reached a staggering total of $12,317 billion cases in all IUU activities. Of all these, the costs of illegal values of missing fish amounted to $10,267 billion dollars, followed by $2,020 billion in unreported activities plus $30.2 million in a span of seven years. In the first three years (2010, 2011, and 2102), illegal shipment of fish from the West African coastal waters hovered at close to a billion and half dollars ($1,459) until it jumped to $1,669 to $1,608 billion and only to rise by $1,831-$1,704 billion from 2013 to 2015 until 2015 when it cracked the $1,996 billion mark. The fiscal equivalence of the losses caused by illicit fishing in the region also involves the unreported values of missing sea food which stood at the identical estimates of $376 million dollars during 2010-2011, and $533 million in 2012. Just as in the remaining years (2013 -2015), the region lost $177 to over 200 million dollars plus, the unregulated side of the unlawful ventures that fluctuated by 0.1-6,2 million to 11.4 and 4.1 million dollars respectively (Table 9). Looking at the regional break down of the known IUU catches from across the waters of Africa, out of the total of 4682,046.896 tons of unreported catches, the region of West Africa and the North Africa alone accounted for about 2664174.316 to 1425485.635 tons representing close to 57% and 30% of the IUU in Africa. While the other regions (Central Africa, Eastern Africa and Southern Africa) in the continent had lower IUU tonnage (342090.885, 173354.1706 and 76941.88931), that is equivalent to 7%, 4% to 2% when compared to the first two regions. Since West Africa stands out as the zone with the highest number of IUU catches. The regional distribution of the economic costs indicates that out of the grand total of $362 billion in liabilities across the continent since 1980. West Africa’s whopping $137.9 billion in exposures outpaced the other areas. The regions of North and South-Central Africa followed up with unreported tonnage costs of $81.2 to $62.8 billion while Central Africa and East Africa each incurred $24.9 to $19.3 billion (Table 10).

|

|

|

3.2. Impact Assessment

- Considering what transpired from illegal fishing activities in West Africa’s coastal zone. Coastal communities in the respective nations endured countless impacts of varying scales with environmental and socio-economic implications.In terms of ecosystem risks, there is growing evidence that the increased volume of fishing activity worldwide is having a very serious effect on the health of the oceans including the Atlantic Eastern Central fishing zone covering the study area. The evidence of ecological effects is such that when commercially prized fishery stocks undergo uncontrolled exploitation, other fish types and resources found in the same ecozone are impacted. Also, current studies show that overexploitation of big shark species leaves in its wake a lasting impact in the available linear network of food web for sharks and growing quantity of species, like rays, that serve as typical target for huge sharks which often lead to declines in smaller fish and shellfish meant for these species. The study area remains at the receiving end of all these.Aside from reaping substantial volumes of fish and marine food to market, massive harvests inadvertently destroy unwanted aquatic creatures, comprising of baby fish, corals as well as other sea floor objects. Destroying these creatures could leave notable impacts on maritime ecology. While the associated impacts on lost ecosystem services and habitat destruction is very considerable. The conventional appraisal of lost potentials and the price of stock recovery for preferred species beginning from 1980s show price tags in the hundreds of billions of dollars for West Africa. In the area, IUU fishing poses a worldwide challenge which impends ocean ecologies and sustainable fishing. Given the harmful effect on fisheries, oceanic ecosystems, food security and coastal communities globally, IUU fishing undercuts domestic and international conservation and management initiatives with threats to the sustainability of shoreline economies in West Africa. Accordingly, overfishing by foreign fleets in West Africa is leading to devastating socio-economic and environmental consequences with the fishing habitats now overstretched beyond their carrying capacity. This in turn inflicts huge damage to fishery stocks through declines and an eventual collapse.From the analysis so far, IUU fishing does not only drive underdevelopment, but it prolongs it by sapping critical income generator essential for development, regional livelihoods and food security. Because this renders the exercise of state authority and fishery management extremely harder. The pains associated with it linger, as the freewheeling offenders roam from one place to another unrestricted, leaving in their wake scores of nations under the worst conditions than they were originally.

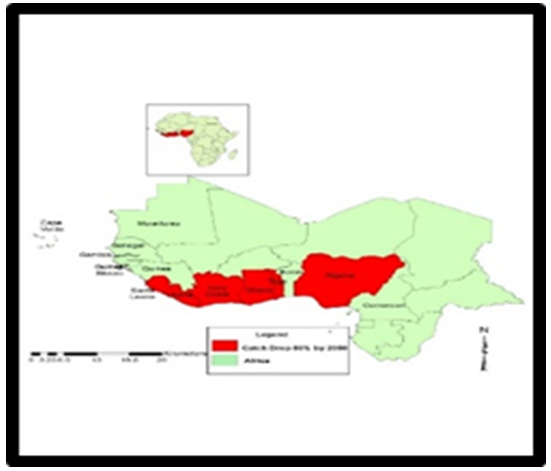

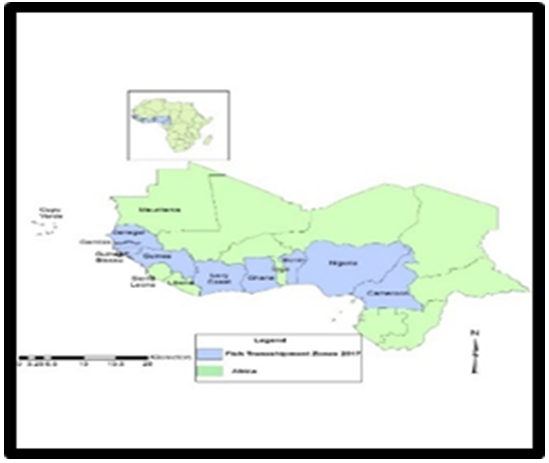

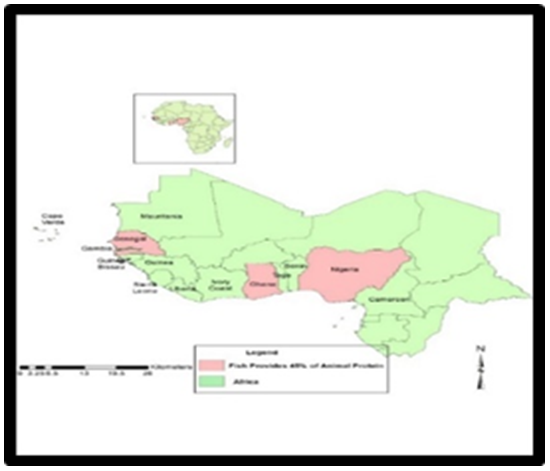

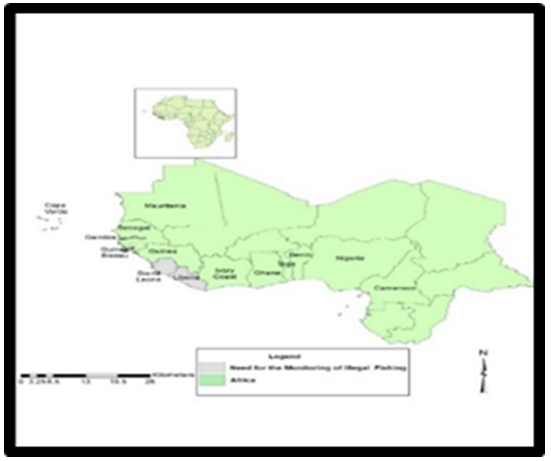

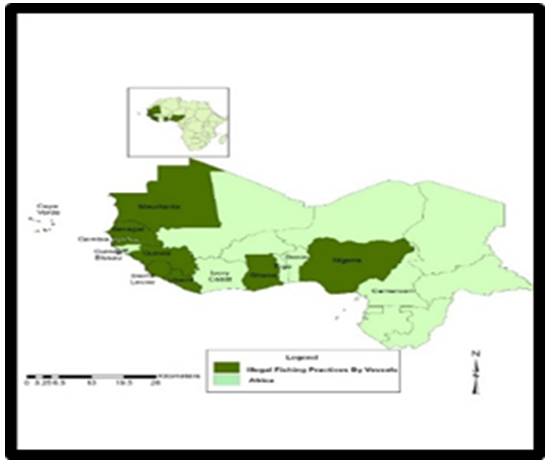

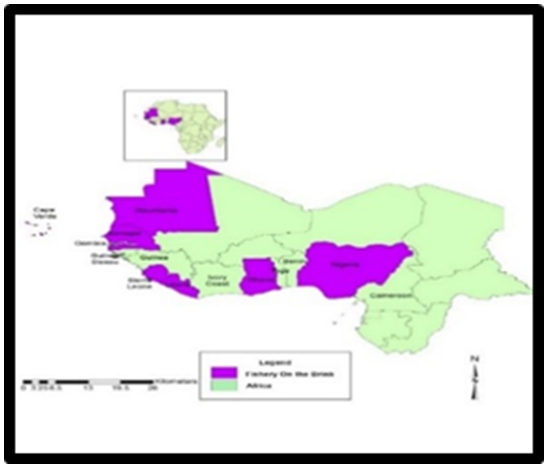

3.3. GIS Mapping and Spatial Analysis

- The GIS analysis consists of the visual display of spatial patterns pinpointing fish catches in the study area, the affected areas and operations involving illegal trawlers off the coast of West Africa. From the activities in the zone over the years, the information as highlighted under different scales and colors reflect the experience of areas hard pressed by the pains of illegal fishing. The capacity to track the geographic contours under a GIS environment as a robust analytical tool, offers hope for uncovering unauthorized fishing in a developing region like West Africa.From the pressures mounted by illegal activities, the anticipated 50% drop in 2050 in fishing stock by overfishing off the coast of West Africa remains overly troubling. As outlined in the map, the affected group of 6 coastal nations in the Lower West African zone stretches through the neighbouring states from Sierra Leone, Liberia on the south west portion to the nearby Ivory coast. The trio of remaining nations (Ghana, Togo, and Nigeria) where fishing zones off the Gulf of Guinea and Atlantic Ocean are under the projected threats face a daunting task to surmount further declines in the study area (Figure 2). From the discomforts left in its wake, the devastating effects of ongoing over fishing and illegal activities are evident in some of the countries in the study area in 2016. The nature of the problem was significantly such, that they were felt in a group of seven different countries located in the Northwest and the Lower South of West Africa. At that pace, the spatial scale of those operations implies that the effects of unauthorized fishing harvests threaten neighbouring nations of Senegal and Mauritania on the Northwest corner of the map represented in thick yellow. Further down on the deep southern edge, emerges a cluster of four other nations (Liberia, Sierra Leone, Ivory Coast and Ghana) regularly besieged by the menace of unauthorized fishing off the coast of West Africa (Figure 3).

| Figure 2. Fish Catch Drop 50% By 2050 |

| Figure 3. Most Significantly Affected Areas |

| Figure 4. Fish Transshipment Zones |

| Figure 5. Fish as 45% of Protein Intake |

| Figure 6. Areas in Need of Monitoring |

| Figure 7. Illegal Fishing Practices by Vessels |

| Figure 8. Fishery on the Brink |

| Figure 9. Annual Fish Production by Nation |

3.4. Factors Responsible for Illegal Fishing Activities

- Regarding the factors driving unauthorized fishing by foreign vessels in West Africa, they do not happen in a vacuum. They are linked partly to a host of physical-environmental, policy, unethical and global factors. These elements are examined fully in the following paragraphs.

3.4.1. Physical and Environmental Elements

- The West African region which ranks highly among the world’s richest fishery grounds teeming with sardines and mackerel stretches thorough millions of kilometres off a vast coastline and Exclusive Economic Zones. The sheer size of this key unprotected frontier of fishing along the Atlantic Eastern central and the Gulf of Guinea current has made it the focus of major scramble in the daily activity of illegal trawlers of various nations from the EU, Asia and others. Even though international regulations of the sea prohibit fishing operations outside of a stipulated 200-mile area off the territory of another nation without permits, the capacity to enforce those rules are hindered due to the shortage of both the expertise and of the massive assets necessary for patrolling such wide maritime areas. Since only quite a few nations in the region, possess the capacity to monitor their coastal fishing waters satisfactorily. Foreign trawlers fishing in the coastal the waters of West Africa operate with impunity regardless of the legality of global conventions.

3.4.2. Ineffective and Contradictory Policies

- Another dimension to the plundering of fishery stocks off the coast of West Africa by illegal activities comes from the wide range of ineffective policies linked with weakness in the capacity of governments to monitor and enforce compliance among the rogue trawlers of other nations. These lapses are often exploited by foreign trawlers subsidized by rich nations through large distant fishing fleets, cheap fuel and insurance in a system where the unmatched coast guards on the West African shorelines are understaffed. In so doing, rich nations using policy instruments at their disposal spend $27 billion yearly in subsidizing those depleting the stocks by propping up illegal fishing. Also, advances in fishing equipment and methods attached to large vessels operating with large subsidies from foreign governments have made it easier for commercial fishing operations to capture more fish, further from home, than ever. Such access level is putting growing pressure on fish stocks and limiting the ability of smaller-scale fishing operations to make a living in West Africa. This is leading to more illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) fishing which is also a major contributor to declining fish stocks and marine habitat destruction.

3.4.3. Unethical Practices by Foreign Trawlers

- One would expect the foreign fishermen patrolling the coast of West Africa to act ethically but that has not always been the case given the current professional records. From what is involved, ethics is an inescapable part of being a professional fisherman and an expert is someone who not only practices a discipline, but who works within the framework of guiding moral principles. Every genuine profession has guiding values that form its public credo; for fisherman, you will expect that these values are articulated in their ethics statements in a way that recognizes the special responsibility of going about their activities without hindering the needs of disadvantaged groups in the coastal communities. However, instead of striving to protect the heritage of the natural environment like the ocean and its resources, illegal foreign fishers continue to wreck the shorelines of West Africa coastal ecosystems. The tendency to bribe West Africans in these circumstances remains a problem since it amounts to providing an accessory to ongoing squander of the region’s marine assets. For that, unethical practices involving the lack of best management practices by illegal fishing operators does contribute to the problems.

3.4.4. Global Activities and Transactions

- The rising incidence of Illegal fish catches in the study area forms part of a much larger global problem that is draining world fishery stocks in which richer nations in Europe and Asia remain the principal actors. Whereas African waters rank highly among the few remaining fishing grounds globally that are still relatively fertile. The ambiguities embedded in global laws regulating the use of fishing grounds in the absence of sustainable fisheries management strategy, lets transnational DWF companies misuse the marine resources of West Africa. Given the coordinated nature of the activities by the nations involved, in the past several years, the West African coastal population have agonized continually from deprivations mounted by the incursions of illegal fishing trawlers from Asia, Russia and the EU. With the inadequacies associated with global regulatory frameworks and science-based management schemes essential to sustainable and equitable fishing activities, excess harvest at the expense of West Africa has now reached overwhelming levels. Under these circumstances, several countries in the region are entrapped regularly by meagre revenues from the marketing of their fishing rights to foreign operators. This comes at a price much lower than the actual market value of the fishery stocks due to the nature of global transactions.

4. Discussion

- The study investigated the extent and form of the menace of illegal fishing by foreign trawlers ravaging vast deposits of the fishery stock beneath the deep waters of West Africa with stress on the issues, ecological analysis and the impacts. Fundamentally significant, are the role of several socio-economic, physical and environmental factors as the driving forces. To carry out the analysis, the research used a mix scale model connected to GIS and descriptive statistics and secondary data collected at the national and regional scale. Aside from the current spate of illegal activities by foreign trawlers happening in the study area. Fish output among the nations from the Republic of Benin to Senegal in the zone from 1980 to 2015 showed considerable variations with Nigeria, Ghana and Senegal as the leading producers based on their totals and averages.From what transpired so far along the West African fishing zone in the AEC, the region saw some level of declines with over 50% of the stocks deemed overfished. The activities of illegal fishing involving others also reached extensive levels that it entailed hundreds of incidents and charges related to violations and irregularities in unauthorized zones by fishing vessels in over half a dozen nations of the West African region from 2000-2013. The accumulated exposure all these years to economic liabilities of illegal fishing for West Africa beginning in 1980 has risen.The spatial analysis of the patterns using GIS mapping, underlined the geographic dispersion of some of the threats from illegal fishing considering the projected declines and the impacts. The others include the trans-shipment zones of missing fish stocks, implications of fishery depletion on food security and vitamin intake in the region and the yearly catches. Aside from the spatial highlights depicting fishing activities, GIS mappings also identified clusters of areas faced with overfishing at the expense of the region. From the impacts, the present scale of unsustainable fishing practices by foreign trawlers should no longer be overlooked West Africa. To remedy the problems, the study proffered (5) solutions. This includes 1) the need for stricter regulation and enforcement; 2) legal actions against offenders; 3) the repatriation of funds from illegal activities; 4) regional cooperation; 5) and monitoring the coastal waters with latest technology from Asia and Europe.

5. Conclusions

- This enquiry analysed the tragedy of unauthorized fishing on the West African coastal waters by foreign trawlers alongside the production levels among the nations in the zone with insightful outcomes itemized as follows. a) fish production potentials in West Africa; b) illegal activities on the rise; c) impacts evident; d) improprieties attributed to various factors; e) mix scale model quite operative.Seeing the challenges off the West African coast as the last frontier of fishing. The total fish production in 1980 to 2015 in the region among the nations from Senegal to Nigeria stands as a testament to the potentials all these years. For that, with the volume of catches over time, fishing waters of the region is characterized by large presence of fishery stocks products that span both marine and inland habitats. Judging the from the scales of activities based on the analysis in the medium category, Ghana saw uptick in tonnage from 1980 to 1985, while the two largest producers (Nigeria and Senegal) outpaced the rest of the countries. In the ensuing periods (1990-1995 and 2010-2015), fish production in Nigeria rose remarkably. Further evidence of vast potential in abundance of marine resources in West Africa comes from the operations in the Atlantic Eastern Central fishing area covering the countries in the region. Being the study areas fishing zone, between 2003-2011, the volume of harvested fish therein rose significantly. The compiling of info on fish output in a zone saddled by illegalities is very commendable in the resource management and coastal zone planning where policy makers require periodic updates on the opening and closing accounts of their resource stock to ensure sustainable use.Going by the litany of challenges faced in the study area, the incidence of illegal fishing involving foreign trawlers has remained on the rise. The gravity of the problem is so rampant on the fishing waters along the Western coast that it involves, active containerized cold fish hubs partaking in the activities to the detriment of the region. In all these, the yearly loss of $1 billion from illegal fishing activities in Africa not only impoverishes the people, but the West African zone as a place where many depend on fishery for survival is now threatened from over fishing. This diminishes the income generation capacity of most communities and self-sufficiency in sea food in the zone. In that way, the misuse of local fisheries by foreign trawlers has now reached unprecedented levels. Because most fish imports consist of unlawful catches from West Africa, these items end up in the EU on yearly basis. Having seen the extent of illegal fishery in the study area, the capacity of this enquiry in tracking these activities and the costs in a manner not seen before remains promising in the search for solutions. Besides, there is an ample possibility for the region and the agencies involved to fully assess the critical thresholds of IUU activities herein as ingredients for new maritime laws in order to ensure the protection of fishery assets.Considering that the scale of over fishing that occurred in the West African fishing waters over the years has had far reaching impacts. The study was solidly on target in identifying the host of physical, environmental and socio-economic and global elements responsible for the problems. With the limitations placed on access to fishing for locals in the study area brought about by the uncertainties in the ecosystem, the policy setting, ethical improprieties and global and transnational activities. The vast size of the West African coastal zone and the potentials makes it a target for fishing by illicit trawlers. Because the nations of West Africa lack the capacity to administer global rules governing fishing in such a vast area, erring fishermen from other continents continue to operate, hence the encroachment on the fishing waters of West Africa. Stressing such inter-linkages from ecological to socio-economic perspective on the missing fishery assets in West Africa region given the limited coverage in the literature does stand out as a major leap in research. The belief is that the capacity of this paper in placing a human face to this tragedy uncovered the experiences of communities threatened by over fishing. The notation of fish indices in the study will be useful as future planning tools likely to impart best management practices and turn illegal trawlers to good stewards of the ecosystem one day.Additionally, the applications of mix scale methodology as analytical tool did stand out. Applying the model made up of descriptive statistics and GIS mapping as working tools ushered in a new approach to regional analysis of illegal fishing. The framework was very effective in delineating the study area and detecting the trends, along with the assembling of info on the elements and host of variables from fish production to changes in fish catches. This technique remains very vital in meeting the needs of researchers focusing on geo-spatial analysis of coastal fishery management. Besides, the geographic mapping of the trends which involves GIS analysis indicates noticeable concentration of nations facing the problems in areas where it has been surging over time. Consequently, the GIS mapping as a planning tool stayed vital in highlighting the dispersion of fishery indices, the pace of their distribution and the scope and scale of their progression across space. This benefit offers a key step towards sound planning given the inaction. The capacity of GIS in pinpointing the changing patterns of illegal vessel paths, depletion, transhipment and monitoring zone over the years remains critical as the region grapples with recovery.Bearing in mind the increasing threats of missing fishery assets across the region and the study outcome, managers and planners will be hard pressed in future to seek urgent answers to many pressing queries germane to recovery, production, containment of IUU activities and unhindered access to fishery by communities. The questions encompass what other challenges will illegal fishers pose to future access? What emerging factors will influence fish production? How will artisanal fishers cope with the damages done to the sector? How will regional and international course of actions curb illegal fishing? Building on the crafting of these queries, there is ample chance for research and interventions to reiterate the emphasis on national and regional attentions linked to eradication of illegal fishery on the coast of West Africa.

Appendix

- Acronyms

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML