-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Food Science and Nutrition Engineering

p-ISSN: 2166-5168 e-ISSN: 2166-5192

2018; 8(4): 95-102

doi:10.5923/j.food.20180804.02

Post-Harvest Loss Vs Food and Nutrition Insecurity; Challenges and Strategies to Overcome in Ethiopia

Abrehet F. Gebremeskel

Department of Food Science and Technology, Hawassa University, Hawassa, Ethiopia

Correspondence to: Abrehet F. Gebremeskel, Department of Food Science and Technology, Hawassa University, Hawassa, Ethiopia.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2018 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

The objective of this review is to provide the magnitudes and causes of post-harvest losses and strategies for loss reduction for improved food and nutrition security. The limited published studies are physiological loss based with no clear image of the extent and causes of post-harvest losses. Approximately half of the Ethiopian agricultural produces and food crops are wasted along the value chain due to inappropriate intervention from farm to fork. Strategies being implemented by actors involved show a remarkable achievement in loss reduction and improve food and nutritional security. Most of the post harvest loss studies conducted were questionnaire based with limited experimental studies and missed the nutritional loss rather than economical. Post harvest loss at consumer’s level was missed. The challenges facing in the agricultural produce and food crop value chain are misunderstanding of the complex physicochemical properties and diverse agricultural commodities at a time. Furthermore, tracking the food and nutritional losses required an integrated and continuing research and development for consolidation and vertical integration among producers, marketing and consumers for improved post-harvest management, food and nutrition security and food safety.

Keywords: Post-harvest loss, Causes, Food and nutrition security, Challenges, Strategies

Cite this paper: Abrehet F. Gebremeskel, Post-Harvest Loss Vs Food and Nutrition Insecurity; Challenges and Strategies to Overcome in Ethiopia, International Journal of Food Science and Nutrition Engineering, Vol. 8 No. 4, 2018, pp. 95-102. doi: 10.5923/j.food.20180804.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

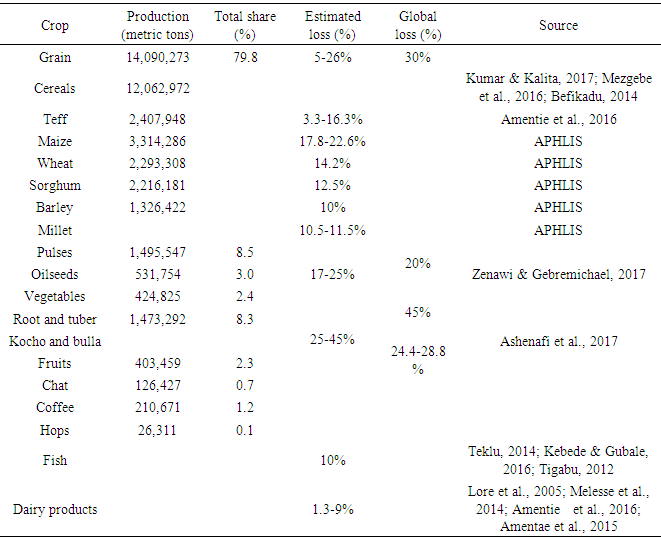

- More than 83% of the Ethiopian are agrarian with subsistence way of living in the rural with inadequate infrastructure (Ethipia World Bank, 2012). Ethiopia, One of the most populated country in the world; 22 million habitant in 1960 reached 108 million in 2018 and expected to be more than 190 million by 2050 (World Bank, 2012; United Nations et al., 2017). The exponential population growth is believed to creates a critical gap in the basic needs of human being (Desta et al., 2017). The basic needs included hygiene and environmental sanitation, disease prevention and control tasks, family health, and health education and communication (Desta et al., 2017), economic collapse, starvation, crop failure and food insecurity (Elias et al., 2017 ; Kumar & Kalita, 2017; Godfray et al., 2010). Ethiopia own a highly diversified agro-ecological condition (Chamberlin et al., 2015; Baye, 2017b) and agriculture is the backbone economy of the country (Welteji, 2018; World Bank, 2012; Alemu et al., 2003). The major agricultural crops produced in Ethiopia are; cereal primarily teff (Eragrostis tef), wheat (Triticum aestivum), maize (Zea mays), sorghum (Sorghum bicolor) and barley (Hordeum vulgare) are staple food crops (Hengsdijk & de Boer, 2017, Cochrane & Bekele, 2018) different pulses species faba bean (Vicia faba L.), field pea (Pisum sativum L.), chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.), lentil (Lens cultinaris Medik.), grass pea (Lathyrus sativus L.), fenugreek (Trigonella foenum-graecum L.) and lupine (Lupinus albus L.) categorized as highland pulses and grown in the cooler highlands (Cochrane & Bekele, 2018; Broek et al., 2014). Haricot bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.), soya bean (Glycine max L.), cowpea (Vigna unguiculata L.), pigeon pea (Cajanus cajan L.) and mung beans are predominantly grown in the warmer and low land areas of the country. The productivity of dominant vegetables in humid area of Ethiopia are tomato, sweet potato, cabbage, onion, hot pepper, beet root, Irish potato, garlic, carrot and Ethiopian mustard (Emana et al., 2015). The potential root and tuber crops cultivated are enset (Ensete ventricosum), potato, taro, yams, anchote, Ethiopian dinish, cassava, tannia and sweet potato. The root and tubers are valued crops to enhance food and nutrition security and have a capacity to survive poor soil and moisture stress (Hengsdijk & de Boer, 2017; MOA, 2015) Tropical fruits and vegetables such as tomato, mango, orange, mandarin, papaya, onion, green pepper, banana, coffee and vegetable (cabbage, khat, pigmented and green leafy vegetable and etc..) and livestock (mainly cattle, sheep, goats and poultry) contributed to the food insecurity reduction (Leta & Mesele, 2014; Dorosh and Rashid, 2013). The productivity of crops and livestock increased with time while the challenges of maintaining safe and quality in the value chain with prolonged storage are worthless. Coffee (Kuma et al., 2018), oil seeds (Gebregergis et al., 2018; Zenawi & Gebremichael, 2017; Dempewolf et al., 2015; Ayana, 2015), spices (Tesfa et al., 2017), fresh fruit and vegetables (Sisay, 2018; Hunde, 2017) and livestock (Tesfay & Teferi, 2017; Eshetu & Abraham, 2016; Alemayehu & Ayalew, 2013) are main export earnings to Ethiopia.Food security had numerous definitions and more than 200 definitions are being published. However, common understanding of food security helps to address food insecurity issues around the globe (Mohamed, 2017; Affognon et al., 2015; Godfray et al., 2010; FAO, 2006). Accordingly, UN Food and Agriculture Organization defined food security based on the World food summit in 1996 as “the physical and economic access to sufficient, safe and nutritious food that meets individual dietary needs and food preferences for an active and healthy life for the entire population at all times, including the four food security pillars; availability, access, utilization and stability” (Gunter et al., 2017; FAO, 2006). Ethiopia has been severing with drought and food insecurity problems for decades and causes irreparable damage to livelihoods of the poor, by reducing self-sufficiency in the long run (Jebena et al., 2017; Ke & Ford-Jones, 2015; Hadley et al., 2008; Ashiabi & Neal, 2007; Dorosh & Rashid, 2013). More than 15 million of the Ethiopian population are food insecure due to EL Niño, land degradation, population pressure, Instability, armed conflict, low agricultural input, low yield and high post-harvest loss (Davis et al., 2017; Savastano & Binswanger-Mkhize, 2014; Chaboud & Daviron, 2017). The causes for high post-harvest losses are many but the leading factors are weak extension services, inadequate pre and post-harvest practices, deterioration and association of outbreak (Mohamed, 2017).The magnitude of post-harvest losses in Ethiopian agriculture and food processing sectors is scarce and the limited published studies are highly variable (Mezgebe et al., 2016; Befikadu, 2014; Hussen et al., 2014; Debela et al., 2011). The post-harvest losses of produces are categorized as food loss and waste begin immediately after harvest (Fusions, 2014). The food is considered as a waste or lost considering the use and destination, edibility and nutritional value of the lost/wasted food in the food life cycle (Bellemare et al., 2017). Food loss or wastage renders nutritional and economic loss (Sheahan & Barrett, 2017; Hodges et al., 2011). The nutritional losses are dynamic and scarce of published data and economic loss are gaining attention associated with quality of physical produce (Akande & Diei-Ouadi, 2010). Post-harvest loss occurred anywhere from farmer’s field to consumer’s plate: at harvest, drying, winnowing, cleaning, storage (on farm, retailer, home), meal preparation and consumption (Sheahan and Barrett, 2017; Kumar and Kalita, 2017). The magnitude of loss is higher during transportation and marketing due to long distance travel with poor infrastructure, price instability, seasonality and market saturation in particular to perishable horticultural crops (Gilbert et al., 2017). One-third of the physical mass of post-harvest produce is lost or wasted around the world (Bellemare et al., 2017) translated to calorie terms was about 23% (Lipinski et al., 2013) and USD 4 billion annually (World Bank, 2011). The post harvest losses of global and Ethiopian agricultural produce are presented in Table 1. According to (FAO, IFAD, & WFP, 2015) reports the global post-harvest loss for cereals, oilseeds & legumes were estimated to be 30% and 20%, respectively. Post-harvest loss of grains in Ethiopia was found in the range of 5-26% between marketing and consumption (Kumar & Kalita, 2017; Mezgebe et al., 2016; Befikadu, 2014). The post-harvest loss of teff (2.2-3.3%) (Minten et al., 2016), wheat (17.1% (12.4% harvesting, 3% storage) (Dessalegn et al., 2017). Zenawi & Gebremichael, (2017) reported that the sesame post-harvest loss was found in the range of 17-25% due to the association of P. interpunctella throughout the sesame producing area to cause a substantial grain loss stored for more than a year. The causes for high loss of grains were improper harvesting including maturity index, moisture content and lack of technical efficiency after harvesting practices including threshing, cleaning, drying, storage, processing and transportation, inefficient processing facilities, biodegradation due to microorganisms and insects etc. For example; Lack of technical efficiency in the storage contributes 50–60% loss and use of scientific storage methods can reduce these losses to as low as 1%–2% (Kumar & Kalita, 2017).

|

2. Limitations during Post-Harvest Loss Studies in Ethiopia

- Most studies were conducted by plant scientist, agricultural economist and post-harvest technologies using a structured questionnaire survey and small experimental analysis. The survey result mostly reveled to physiological post-harvest loss estimation of discarded or food/commodity no longer acceptable for consumption. The coverage of post-harvest loss assessment was small in terms of commodity, geographical location and no studies were conducted at consumer level.

3. Strategies to Reduce Food Wastage and Food Insecurity

- The Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) estimates that 70% more food needs to be available by 2050 for the projected population size (Hodges et al., 2011). Reducing food loss/wastage contributes to the anticipated global food demand and improve food security (Affognon et al., 2015; Dorosh & Rashid, 2013; Hodges et al., 2011). FAO developed ‘twin-track approach’ priority policy to fight food insecurity, sustain agricultural and rural development. The first track is establishment of recovery measures for resilient food system including food economy structure from production following the value chain to consumption. The second track is assesses options of vulnerable groups support. The economic reform of the growth and transformational plan (GTP) in Ethiopia showed a remarkable achievement as the economic performance and macroeconomic stability attained and poverty level declined from 49.5% in 1994/95 to 29.2% in 2009/10 and the food poverty head count index also declined from 38% to 28.2% between 2004/05 and 2009/10 (The Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, 2016). However, poverty still affects more than 15 million populations’ and a collective approach is needed for loss reduction. Grain loss reduction lonely in sub-Saharan Africa is believed to be enough in providing the minimum food requirements for about 48 million habitants and contribute significantly to the Zero Hunger Challenge (FAO, IFAD, and WFP, 2015).The five strategies designed to overcome food insecurity, food wastage reduction and sustain economic growth in Ethiopia are (1) Sustaining growth in crop and livestock production through diversified agro -processing of local and global investors (2) Increasing market efficiency (3) Providing effective safety nets launched in 2005 (4) Maintaining macroeconomic incentives and stability and (5) Managing the rural–urban transformation to improves the post handling of agricultural produce. Proper post-harvest of produce improved the quality, protect from cross contamination and increases the income by reducing losses, overcoming the socioeconomic constraints, such as inadequacies of infrastructure, poor marketing systems, weak R&D capacity, encouraging consolidation and vertical integration among producers and marketers. The four critical points identified to attain the strategies, improve post-harvest management and food and nutrition security (Kummu et al., 2012) are; 1. Knowledge, attitude and practice of smallholder farmers, development agents, youths and others on postharvest management improved; 2. Human resource and institutional capacitating on postharvest management strengthened; 3. Food practice options for reducing postharvest losses are compiled, disseminated and scaled up and out to small holder and 4. Postharvest management policy and strategy formulated.For the success of the strategies, the country designs and continuing implementing Agricultural Development Led Industrialization (ADLI) to attain a high nutritional status food, improved post-harvest management, reduced post- harvest losses, production of value added products, effective and efficient research programs on the post-harvest sector strengthened and promoted (The Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, 2016; Zewdie, 2015; Gudeta, 2009). Good Handling practices during harvesting, precooling, cleaning and disinfecting, sorting and grading, packaging, storing, and transportation played an important role in maintaining quality and extending shelf life using appropriate postharvest treatments like refrigeration, heat treatment, modified atmosphere packaging (MAP), and 1-methylcyclopropene (1- MCP) and calcium chloride (CaCl2) application is vital (Arah et al., 2015). Hence, comprehensive evidence on the nature, magnitude, costs, and value of current post harvest losses of various groups of commodities along the value chain has to be clearly stated to reduce post-harvest loss, improve food and nutrition security and improve the income level.

4. Challenges to Overcome Food Insecurity

- The challenges to minimize post-harvest loss and ensure food security in Ethiopia are many. The most and critical ones are fast urbanization, dynamic population growth, use of fertile land for non-food application, climate change, consumption habit change, unattainable and lack of integrated technology and limited land size (Godfray et al., 2010). According to Kumar & Kalita, (2017), one -third of food is wasted in the post-harvest operations. The incidences of high post-harvest in Ethiopia was reported in different study due to the association rodents/pests/insects attack, damage due to inadequacy pre-harvest and post-harvest practices, microorganism grown during prolonged and uncontrolled storage, climate condition, harvesting and processing was contributing to high post-harvest of durable crops (Hodges et al., 2011). The losses along the supply chain of the agricultural produce were estimated to be 20-50% of the total production including harvesting (threshing), transportation, storage in the field, market, industry, processing and consumption (World Bank, 2011; Parfitt et al., 2010; Lundqvist et al., 2008). Studies were conducted in the value chain but the consumption related losses are missed (Hengsdijk & de Boer, 2017). The main cause for high post-harvest losses were found long distance travel from the main road and nearest market, latitude (Hengsdijk & de Boer, 2017) and high seasonal variation in temperature enhance metabolism, respiration, growth of microorganisms, poor storage and packaging systems, non-uniform rainfall distribution, lack of market access, lack of transportation and interference of broker (Hengsdijk & de Boer, 2017; Arah et al., 2015).Providing adequate and safe food based on the daily diet requirement to more than 106 million population is a challenge (Parfitt et al., 2010; World Bank, 2011). To feed the estimated population, agricultural productivity is expected to grow by 50–70% to secure the food requirement all the time (Desta et al., 2017; Nations et al., 2017; World Bank, 2012). Thought, post-harvest loss reduction remain a challenge due to the technology used is outdated and limited awareness (Hodges et al., 2011; World Bank, 2011; Gustavsson et al., 2011), misunderstanding of the nature of the produce and magnitude of loss in the right value chain. Challenges towards post-harvest reduction, food and nutrition food security in Ethiopia are; Ÿ Limited funding not higher than 5% globally, in Ethiopia it was almost neglected. Ÿ The post-harvest loss estimations are mostly done based on physiological or economic aspects rather nutritional and quality base. Ÿ Lack of quality parameter and nature of animated system understanding for each crop produced, Ÿ Association of toxins during durable crop storage (Udomkun et al., 2017).Ÿ Flexibility of the farming and complexity of the nature of the agricultural food crops and weather condition (Baye, 2017a).Ÿ Limited or negligible science based and simple post-harvest/food Science technology based on the nature of the food produce (Kitinoja et al., 2011) in identifying the cause and sources of losses.Ÿ No studies were conducted on qualitative losses (caloric intake, nutritional composition loss, loss of acceptability and edibility).

5. Conclusions

- Ethiopia owed a diversified agro ecological condition and abundant agricultural commodity is produced. Although, millions of Ethiopian are food insecure due to natural constraints and inappropriate practices in the value chain of agricultural commodities. One third of the global agricultural commodities are lost and 20-50% of the Ethiopian commodities are lost and highly variable depending on their nature and practices. Most studies report lacked consistency of coverage of the commodities, location and survey. Furthermore, tracking the food and nutritional losses required an integrated and continuing research and development which motivated the consolidation and vertical integration among producers, marketing and consumers for improved post-harvest management, food security and food safety.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML