-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Food Science and Nutrition Engineering

p-ISSN: 2166-5168 e-ISSN: 2166-5192

2018; 8(3): 60-71

doi:10.5923/j.food.20180803.02

Postharvest Ultraviolet Light Treatment of Fresh Berries for Improving Quality and Safety

Arosha Loku Umagiliyage, Ruplal Choudhary

Department of Plant, Soil and Agricultural Systems, Southern Illinois University Carbondale, IL, USA

Correspondence to: Ruplal Choudhary, Department of Plant, Soil and Agricultural Systems, Southern Illinois University Carbondale, IL, USA.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2018 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Ensuring food safety and freshness of fresh produce is always challenging because of a variety of microbial contamination in the field by soil and water, wild or domesticated animals, as well as during harvest and postharvest operations by contaminated workers, tools and packaging materials. A thermal kill process in fresh produce is not practical due to loss of freshness and quality. A nonthermal process to decontaminate and improve food safety is urgently required to improved food safety in fresh produce Industry. Although the Food Safety Modernization act recommends general agricultural practices and farm food safety rules, a kill step for human pathogens and spoilage organisms in food produce will help the fresh produce industry preventing recalls. Ultraviolet light is a promising sanitation technology to enhance food safety in produce industry. The article reviews the principles and applications of germicidal ultraviolet in fresh produce in general and berries in particular. A wide range of research on fresh produce shows promising use of ultraviolet light in berries with significant inhibition of pathogenic and spoilage bacteria and fungi on fresh produce. Innovative design of ultraviolet light delivery equipment that enables exposure of whole surface of produce will promote rapid adoption of this low cost sanitation technology readily available for the produce industry.

Keywords: Postharvest ultraviolet light treatment, Berries, Fruit decay, Shelf-life, Food safety, Fresh produce

Cite this paper: Arosha Loku Umagiliyage, Ruplal Choudhary, Postharvest Ultraviolet Light Treatment of Fresh Berries for Improving Quality and Safety, International Journal of Food Science and Nutrition Engineering, Vol. 8 No. 3, 2018, pp. 60-71. doi: 10.5923/j.food.20180803.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

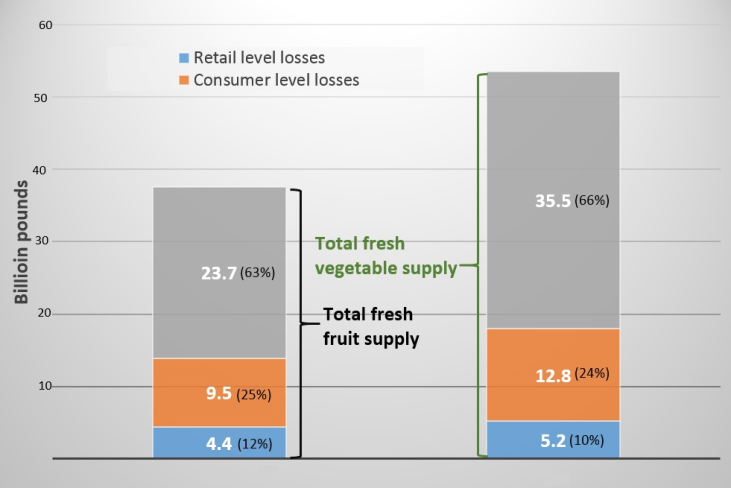

- Fruits and vegetables (F & V) are essential constituents of a well-balanced healthy diet. By adding sufficient amount of F & V into one’s daily meal, one may enhance human wellbeing by reducing the risk of some chronic diseases such as heart diseases, type 2 diabetes [1], certain types of cancers [2] and obesity [3]. Moreover, higher dietary fiber in F & V helps to reduce inflammatory digestive track diseases and constipation [3, 4]. As per WHO (2004), insufficient intake of F &V was liable for loss of labor force equivalent to 16.0 million worker-years and 1.7 million (2.8%) of deaths around the world [4]. Therefore, USDA recommends consuming at least 2 cups of fruits daily per person over 19 years to avoid health issues [3]. Although there are enormous health benefits of F & V, approximately one-third of world production was unavailable for human consumption due to postharvest spoilage. The Economic research service of USDA estimated the annual fresh fruit supply in 2010 (Figure 1) was 37.6 billion pounds, from which 4.4 and 9.5 billion pounds were lost at retailer level and consumer level respectively, adding together it was 37% lost for fresh fruit due to spoilage or undesirable to consume. Similarly, the total loss was 34 percent for fresh vegetables [5]. Moreover to emphasize the severity, total loss of fruit and vegetable lost was equivalent to 99.2 billion dollars, which was nearly 58% of F & V production to spoilage in the US [5].

| Figure 1. Estimated fruit and vegetable losses in the U.S. in 2010 (data source: [5]) |

1.1. Why are Berries Important in Diet and Their Issues?

- Berries mainly blueberries, strawberries, raspberries, and blackberries are popular fruit, providing a number of nutrients and owning a nutritional aura through their many known health benefits. Though it is not yet officially defined by any controlling institution; berries can be considered as “super fruits,” which are remarkably high in those nutrients and antioxidants that can provide potential health benefits beyond berries’ nutritional values. Anthocyanin is a flavonoid found in most berries, which provide prominent color to berries and acts as an antioxidant and also an anti-inflammatory. Bioactive compounds may prevent several chronic illnesses related to oxidation and inflammation in berries. There was a recent study showing that the blood pressure of stage 1 hypertension patients dropped their blood pressure significantly by administrating blueberry powder after eight weeks [7]. Blood pressure and arterial stiffness were reduced by daily blueberry intake that was hypothesized by Johnson et al. (2015) as increased nitrogen oxide production with blueberry consumption. Basu, Rhone and Lyons (2010) have revealed (using human subjects) significant improvements in low-density lipid oxidation, lipid peroxidation, total plasma antioxidant capacity, and glucose metabolism by consuming many kinds of berries [8]. Even though the conclusive evidence was not provided, many types of research support the recommendation of berries as super fruit [7, 8]. Blueberry has shown a correlation in improving memory in those mice that had lost memory due to a high-fat diet for an extended period [9]. Similarly, Whyte & Williams (2015) reported improvement in the cognitive domain of school children aged 8-12. So, blueberry may have positive effects on human memory boosting [10].Once berries are harvested for fresh consumption, they are either packed directly in retail containers in the field or placed in a packinghouse without washing or minimally handling because of their highly perishable nature. Fungicides application, cold storage, extra careful handling and controlled atmosphere packaging are common control methods against the post-harvest microbial decay of F & V [11-13]. However, most of these methods have drawbacks that are unfavorable for fresh berries by various means. Berries may be washed before freezing, but they are not usually blanched or heat treated unless they are used to make preserves or other processed products. Thus, there is typically no “kill step” that would eliminate pathogens or spoiling organisms in fresh or frozen berries. Some berries such as blackberries, raspberries, and strawberries, have many dimples and fiber-like projections that are best place for microbes or dirt to hide easily preventing mild wash out [14]. As those berries’ skin are relatively thinner, they are higher vulnerable to breakage. Epidermal injuries may lead to invading the inner tissues of the berries leading to spoilage and unsafe for consumption. Simply dipping fresh berries in water or disinfecting liquid, may not completely remove biofilm on the surface as characteristic of the surface is more beneficial towards microbial attachment. Therefore, alternative methods of disinfection of berries are recommended for enhancing the food safety and extending the shelf life.

1.2. Objective of the Review

- Health issues for the consumer, lower shelf life, spoilage, and food safety issues of berries make a significant amount of financial losses. Additionally, restrictions on use of certain chemicals and limitation in the applicability of microbial control methods for berries create an opportunity for potential use of ultraviolet (UV) light treatment on berries. Therefore, the objective of this paper is to summarize the available research findings and make a review of current and future potentials of surface UV light treatment for the berries. Later part of the article is more focussed on UV treatments of blueberry.

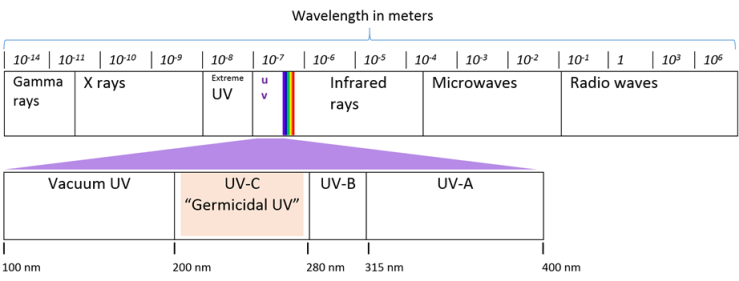

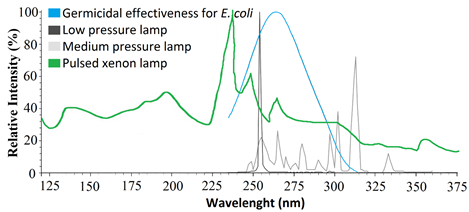

2. Ultraviolet Light

- UV light has wavelength ranges from 100 to 400 nm in the electromagnetic spectrum. As plants use sunlight for photosynthesis, they are exposed to the UV radiation to some extent. UV radiation is divided into four segments (Figure 2) namely, vacuum UV from 100 to 200 nm; short-wave ultraviolet (UV-C), from 200 to 280 nm; UV-medium wave (UV-B), from 280 to 320 nm; and UV-long wave (UV-A), from 320 to 400 nm [15].Highest germicidal effectiveness shows at wavelengths between 255–265 nm that is within the range of UV-C region. Bacterial DNA absorbs the high amount of UV rays near 255-260 nm area, which provides evidence of maximum germicidal effectiveness in UV-C (Figure 3). Different type of UV bulb produce a spectrum of different wavelengths such as low-pressure lamps produce mainly 250-260nm, medium pressure lamps produce 240-340nm whereas entire UV spectrum range can be obtained by using pulsed xenon lamp [15]. Most of the commercially available germicidal UV lamps are made to emit more than 90% of its energy in the wavelength of 254 nm. Falguera, Pag´an, Garza, Garvin, and Ibarz (2011) and Kowalski (2009) described the classification of ultraviolet radiation source depend on a range of emission spectrum and highest concentration wavelength emitted [15, 16].

| Figure 2. Four ultraviolet regions in the electromagnetic spectrum |

| Figure 3. Germicidal effectiveness for E. coli and comparisons of generated spectrum by different types of lamps [15-17] |

2.1. How does the UV Damage the Microbes?

- Ultraviolet light can damage cellular constituents such as genetic material and proteins. More serious damages aim at genetic materials lead to microbial inactivation. Damage severity depends on wavelength region of UV. The creation of nucleic material photoproducts is mainly caused by wavelength region responsible for UV-C [15]. Pyrimidine nucleic acid bases in genetic material show several times higher absorbance of photon energy than purine bases, which makes lethal damage to microbes by producing relatively higher amount of cyclobutane pyrimidine dimers (CPDs) with compare to lesser amount of pyrimidine 6–4 pyrimidone photoproducts (6-4PPs) [17]. Covalent bonds are formed to make CPDs or 6-4PPs between two adjacent pyrimidine bases namely thymines, cytosines, or cytosine and thymine bases, depending on relative nucleotide sequence [17, 18].Other than the CPD and 6-4PPs, spores of microbes can make a different kind of photoproduct between adjacent thymine namely 5-thyminyl-5,6-dihydrothymine [18]. Any photoproduct formed by UV radiation energy affects the genetic material replication and RNA transcription. Structural anomalies in genetic material suppress essential gene expressions that are leading to lethal mutations in microbial cells. The severity of lethal mutagenesis is higher in 6-4PPs followed by CPD and the least in 5-thyminyl-5,6-dihydrothymine [17]. In bacterial spores, the formation of CPD and 6-4PPs are hundred times lesser than 5-thyminyl-5,6-dihydrothymine formation, and later photoproduct can be easily rectified into original thymine bases at spore germination [19]. Therefore spores show less vulnerability to UV irradiation than vegetative bodies.Ultraviolet photo-oxidation of cell materials mainly proteins, lipids, and sterols may also effect on microbial suppression mechanism. Photo-oxidation damages occur mostly to tryptophan, tyrosine, histidine, and cysteine amino acid residues and most prominent protein damage happen indirectly forming reactive oxygen species inside chain residue. Photo-oxidation may cause changes in physical and chemical assets of protein that alters the essential usefulness of protein to the microbes [17]. Yet, the principal mechanism of microbial irradiation is a genetic material modification.

2.2. Configuration of Ultraviolet Processing Systems

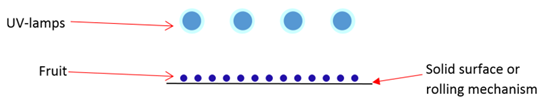

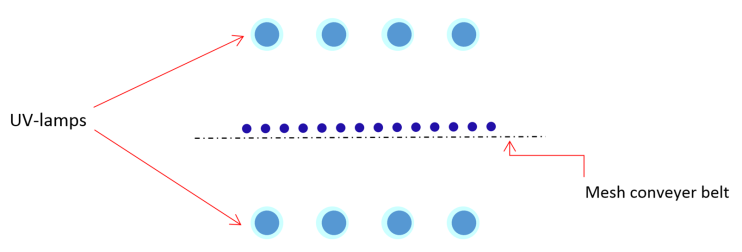

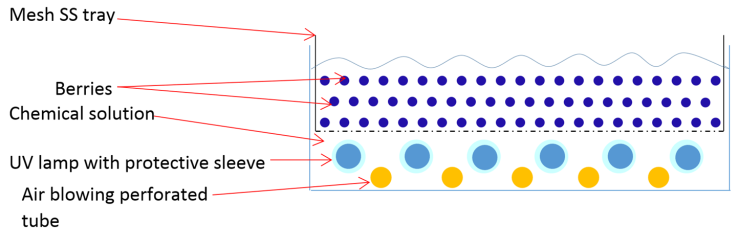

- The external surface area needs to be exposed to the radiation emitted by UV lamps in the surface treatment of fruits. To achieve that purpose, UV lamps and fruit have to arrange in particular way that can deliver a sufficient dosage of UV-C light to fruit surface in a defined period. In literature, the UV processing devices or geometry of arrangement varied by individual research group or manufacturers. The device configurations were highly influenced by characteristics of fruits such as size, shape, and other surface characteristics [20]. The finding of Adhikari et al., (2015) revealed that antimicrobial efficacy of UV-C light radiation was lower in strawberry and raspberry in comparison to berries having smoother surface properties [20]. The UV treatment device can be categorized into three categories (Figure 4a, 4b, 4c) based on lamp arrangement in the administration of UV-C. Figure 4a illustrates a conceptual device that has an ultraviolet source on one side (top). Fruits lay on a solid surface, or there is a rolling mechanism to rotate berries with a spherical shape.

| Figure 4a. Top illumination UV lamp arrangement on one side of berries |

| Figure 4b. Top and bottom illumination UV lamp arrangement on both side of berries (two side exposure) |

| Figure 4c. A Water or sanitizer solution assisted bottom illuminated - UV lamp arrangement |

3. UV Treatment of Fruit

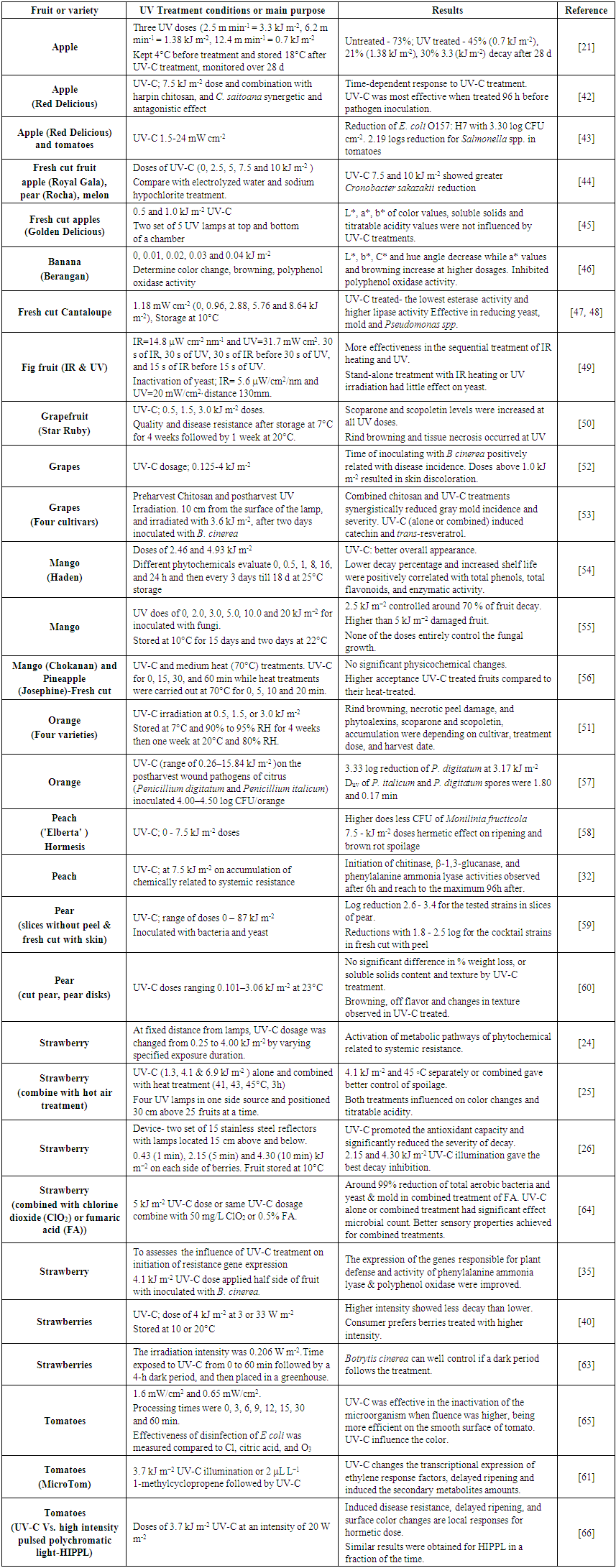

- When looking for an alternative to the conventional control method of microbial elimination, significant attention has been raised about the ultraviolet light treatment of fresh fruit to artificial UV-C light in the range of 200-280 nm. The US food and drug administration (2011) have approved commercial use of UV-C (253.7 nm wavelength) generally emitted by low-pressure mercury lamps, for food processing and treatment of fruit to reduce surface microorganisms [31]. Most of the commercially available germicidal lamps produce more than 90% in 254 nm or closer. Researches have shown that UV-C could induce resistance of fruit and vegetables to postharvest spoilage as well as delayed the ripening process for extending the shelf life [32]. Further UV can induce bioactive compound production (polyphenols, anthocyanin) in fruits [33]. Moreover, when used at an ideal level, UV-C light induces systemic acquired resistance or build-up of phytoalexins to prevent further invasion [34]. Most likely, that play a major role in the disease resistance of many plant systems and activates genes encoding to produce pathogenesis- related proteins [35, 36].The initiation of resistance to fungal rot has shown a higher correlation with the buildup of an isoflavone reductase-like protein in grapefruit by exposing to UV [37]. Similarly, the initiation of phenylalanine ammonia lyase, chitinase, and -1,3-glucanase activity was increased with UV-C illumination in peach [32] and citrus fruit [38]. In addition to the induction of disease resistance, UV-C treatment was attributed to the delayed ripening, the inhibited ethylene production in fruit [39]. As a result of differed ripening and inhibition of the expression of cell wall degrading enzyme (pectin methylesterase, polygalacturonase, and cellulose) activities by UV treatment prolonged the freshness of fruit and enhanced consumer preference [39, 40].Treatment with UV-C light offers several advantages to food processors as it does not leave any residue in treated food [34], is easy to use and lethal to most types of microorganisms, and does not require extensive safety equipment to be implemented [41]. Although advantages of UV is well known, researchers have been exploring for efficient use of UV in produce industry for enhancing UV light use. Table 1 summarizes the review of literature of UV treatment of fruit.

| Table 1. Summary of the Literature Review on UV Treatment of Fruit |

cm-2 nm-1), UV irradiation (31.7 mW cm-2), and their combination was tested for the surface illumination and duration of storage [49]. Immediately after the testing; 30 s of single treatments with IR heating; and UV irradiation inactivated about 1 and 2.5 logs in comparison with control, respectively. About 3 logs reduction were resulted by 30 s of IR followed by 30 s UV exposure before the storage. The subsequent treatments helped to retain fig fruit quality as well as food safety during storage. Further, subsequent exposure of IR and UV controlled the growth of isolated Rhodotorula mucilaginosa whereas single treatment method didn’t show good inactivation. Quality and disease resistance of grapefruit were determined by exposure of three different doses of UV-C (0.5, 1.5, 3.0 kJ m-2), and after storage at 7°C and 90−95% relative humidity (RH) for four weeks followed by a week at 20°C to mimic the store shelf conditions [50]. Higher doses did not significantly reduce decay incidence, but citrus peel browning and tissue necrosis occurred at higher treatment doses. The phytoalexins (scoparone and scopoletin) levels were increased at all UV doses, and greater accumulation observed with higher treatment dosage [50]. Both phytoalexins showed the nondetectable level in untreated grapefruit, and soluble solids and titratable acidity did not show significant changes [50]. The same UV-C treatment and storage condition were applied in four different varieties of oranges in another research showed a similar trend of phytoalexins accumulation depending on cultivar, treatment dose, and harvest date [51]. But in the later study, decay percentage reduced significantly with increasing dosage for late season harvested ‘Washington Navel’ and ‘Biondo Comune’ oranges.UV-C irradiation-induced disease resistance in grapes was investigated by Nigro, Ippolito & Lima, 1998. Botrytis cinerea was inoculated by piercing the surface of grapes at 0, 24, 48, 72, 96 and 144 h after irradiation of different dosage (0.125-4 kJ m-2) [52]. Significantly lower numbers of diseased grapes and smaller lesion diameter were found in berries illuminated with doses between from 0.125 to 0.5 kJ m−2. Grapes irradiated 24-48 hours before inoculating with Botrytis cinerea showed a lower disease incidence than those inoculated immediately before irradiation [52]. Also, Doses above 1.0 kJ m-2 resulted in skin discoloration. Treatment within 0.25 and 0.5 kJ m−2 did not significantly decrease a number of epiphytic yeasts, which showed antagonism towards pathogenic molds. The research by Nigro et al., 1998 suggested UV-C could induce the resistance in fruit to gray mold [52]. In another study about four different cultivar of grapes (Thompson, Autumn Black, Emperor, and green grape selection B36-55) investigated the influence of UV-C alone or with preharvest spraying of chitosan on catechin & resveratrol contents, chitinase activity and effectiveness of controlling gray mold in grape [53]. Combined chitosan and UV-C treatment showed a few decay incidence and severity compared with either treatment alone. Further, UV-C irradiation, alone or combined with chitosan treatment induced catechin and trans-resveratrol content in grapes [53].The effects of UV-C treatment (doses of 2.46 and 4.93 kJ m-2) on the biochemistry and quality of mango fruit were evaluated at 0, 0.5, 1, 8, 16, and 24 h after treatment followed by every third day till 18 day at 25°C storage [54]. Lower decay percentage and increased shelf life correlated positively with total phenols, total flavonoids, the enzymatic activity of phenylalanine ammonia-lyase and lipoxygenase. Further, UV-C maintained better overall appearance [54]. Recently in another research, higher UV-C dosage was evaluated on five different mango decaying fungi in-vitro as well as artificially inoculated into mangos with UV doses of 0, 2.0, 3.0, 5.0, 10.0 and 20 kJ m−2 for inoculated with Botryosphaeria dothidea and Colletotrichum gloeosporioides [55]. Illumination up to 59.7 kJ m−2 was provided for Lasiodiplodia theobromae, Alternaria alternate, and shelf life simulated was done bystoring at 10°C for 15 days and two days at 22°C. The results of the later research revealed following: 2.5 kJ m−2 controlled around 70% of fruit decay; higher than 5 kJ m−2 caused damage on peel leading to decay severity, and none of the doses completely controlled the fungal growth in in vitro experiments [55]. However, research completed on fresh cut mango and pineapple in 2015 concluded the extension of shelf-life to 15 d, higher consumer preference, and efficient control of total mold count following UV-C treatments [56].Survival of Penicillium digitatum and Penicillium italicum were examined on inoculated navel oranges (4.00-4.50 log CFU per orange) by exposing to eight different UV-C doses in the range of 0.26-15.84 kJ m-2 [57]. Around 3 log reduction of P. digitatum were observed at the UV-C dose of 3.17 kJ m-2 whereas P. italicum showed higher resistance; and 2.5 log CFU/orange reductions were obtained even with the highest UV-C dose [57]. Further, the UV-C doses that resulted in 90% decrease in the number of survivors were 1.80 and 0.17 min for P. italicum and P. digitatum spores respectively. The germicidal and hormesis effects on reducing brown rot of ‘Elberta’ peaches were evaluated with UV-C dosage range 0 - 7.5 kJ m-2 [58]. Lower Monilinia fructicola lesions were observed with increasing dosage. Additionally, the result of the study revealed the beneficial effect of ultraviolet treatment that increased phenylalanine ammonia-lyase activity, induced host resistance, delayed ripening and suppressed ethylene production [58]. El Ghaouth, Wilson, & Callahan, 2003 also reported the UV-C dosage of 7.5 kJ m-2 on Peach had a positive effect on the accumulation of chemicals related to systemic acquired resistance [32]. Also, the result of the later study indicated that initiation of chitinase,

cm-2 nm-1), UV irradiation (31.7 mW cm-2), and their combination was tested for the surface illumination and duration of storage [49]. Immediately after the testing; 30 s of single treatments with IR heating; and UV irradiation inactivated about 1 and 2.5 logs in comparison with control, respectively. About 3 logs reduction were resulted by 30 s of IR followed by 30 s UV exposure before the storage. The subsequent treatments helped to retain fig fruit quality as well as food safety during storage. Further, subsequent exposure of IR and UV controlled the growth of isolated Rhodotorula mucilaginosa whereas single treatment method didn’t show good inactivation. Quality and disease resistance of grapefruit were determined by exposure of three different doses of UV-C (0.5, 1.5, 3.0 kJ m-2), and after storage at 7°C and 90−95% relative humidity (RH) for four weeks followed by a week at 20°C to mimic the store shelf conditions [50]. Higher doses did not significantly reduce decay incidence, but citrus peel browning and tissue necrosis occurred at higher treatment doses. The phytoalexins (scoparone and scopoletin) levels were increased at all UV doses, and greater accumulation observed with higher treatment dosage [50]. Both phytoalexins showed the nondetectable level in untreated grapefruit, and soluble solids and titratable acidity did not show significant changes [50]. The same UV-C treatment and storage condition were applied in four different varieties of oranges in another research showed a similar trend of phytoalexins accumulation depending on cultivar, treatment dose, and harvest date [51]. But in the later study, decay percentage reduced significantly with increasing dosage for late season harvested ‘Washington Navel’ and ‘Biondo Comune’ oranges.UV-C irradiation-induced disease resistance in grapes was investigated by Nigro, Ippolito & Lima, 1998. Botrytis cinerea was inoculated by piercing the surface of grapes at 0, 24, 48, 72, 96 and 144 h after irradiation of different dosage (0.125-4 kJ m-2) [52]. Significantly lower numbers of diseased grapes and smaller lesion diameter were found in berries illuminated with doses between from 0.125 to 0.5 kJ m−2. Grapes irradiated 24-48 hours before inoculating with Botrytis cinerea showed a lower disease incidence than those inoculated immediately before irradiation [52]. Also, Doses above 1.0 kJ m-2 resulted in skin discoloration. Treatment within 0.25 and 0.5 kJ m−2 did not significantly decrease a number of epiphytic yeasts, which showed antagonism towards pathogenic molds. The research by Nigro et al., 1998 suggested UV-C could induce the resistance in fruit to gray mold [52]. In another study about four different cultivar of grapes (Thompson, Autumn Black, Emperor, and green grape selection B36-55) investigated the influence of UV-C alone or with preharvest spraying of chitosan on catechin & resveratrol contents, chitinase activity and effectiveness of controlling gray mold in grape [53]. Combined chitosan and UV-C treatment showed a few decay incidence and severity compared with either treatment alone. Further, UV-C irradiation, alone or combined with chitosan treatment induced catechin and trans-resveratrol content in grapes [53].The effects of UV-C treatment (doses of 2.46 and 4.93 kJ m-2) on the biochemistry and quality of mango fruit were evaluated at 0, 0.5, 1, 8, 16, and 24 h after treatment followed by every third day till 18 day at 25°C storage [54]. Lower decay percentage and increased shelf life correlated positively with total phenols, total flavonoids, the enzymatic activity of phenylalanine ammonia-lyase and lipoxygenase. Further, UV-C maintained better overall appearance [54]. Recently in another research, higher UV-C dosage was evaluated on five different mango decaying fungi in-vitro as well as artificially inoculated into mangos with UV doses of 0, 2.0, 3.0, 5.0, 10.0 and 20 kJ m−2 for inoculated with Botryosphaeria dothidea and Colletotrichum gloeosporioides [55]. Illumination up to 59.7 kJ m−2 was provided for Lasiodiplodia theobromae, Alternaria alternate, and shelf life simulated was done bystoring at 10°C for 15 days and two days at 22°C. The results of the later research revealed following: 2.5 kJ m−2 controlled around 70% of fruit decay; higher than 5 kJ m−2 caused damage on peel leading to decay severity, and none of the doses completely controlled the fungal growth in in vitro experiments [55]. However, research completed on fresh cut mango and pineapple in 2015 concluded the extension of shelf-life to 15 d, higher consumer preference, and efficient control of total mold count following UV-C treatments [56].Survival of Penicillium digitatum and Penicillium italicum were examined on inoculated navel oranges (4.00-4.50 log CFU per orange) by exposing to eight different UV-C doses in the range of 0.26-15.84 kJ m-2 [57]. Around 3 log reduction of P. digitatum were observed at the UV-C dose of 3.17 kJ m-2 whereas P. italicum showed higher resistance; and 2.5 log CFU/orange reductions were obtained even with the highest UV-C dose [57]. Further, the UV-C doses that resulted in 90% decrease in the number of survivors were 1.80 and 0.17 min for P. italicum and P. digitatum spores respectively. The germicidal and hormesis effects on reducing brown rot of ‘Elberta’ peaches were evaluated with UV-C dosage range 0 - 7.5 kJ m-2 [58]. Lower Monilinia fructicola lesions were observed with increasing dosage. Additionally, the result of the study revealed the beneficial effect of ultraviolet treatment that increased phenylalanine ammonia-lyase activity, induced host resistance, delayed ripening and suppressed ethylene production [58]. El Ghaouth, Wilson, & Callahan, 2003 also reported the UV-C dosage of 7.5 kJ m-2 on Peach had a positive effect on the accumulation of chemicals related to systemic acquired resistance [32]. Also, the result of the later study indicated that initiation of chitinase,  and phenylalanine ammonia lyase activities were observed after 6 h and reached to the maximum 96 h after ultraviolet light treatment. Sliced pear without peel or fresh cut pear with peel were inoculated with Listeria innocua, Listeria monocytogenes, Escherichia coli, for yeast Zygosaccharomyces bailli, Zygosaccharomyces rouxii, Debaryomyces hansenii, and evaluated for the efficacy of UV-C treatment range from 0 to 87 kJ m-2 [59]. The effectiveness of UV-C was lower for the slices of pear with peels (1.8 - 2.5 log reduction for the cocktail strains) whereas the higher reduction in the range of 2.6 - 3.4 log were observed for without peels [59]. Moreover, while the survival patterns for the different microorganisms had a similar trend, the resistance determined by the type of microorganism and method of slices process. In another research inactivation of Penicillium expansum in cut pears (pear disks) were examined by exposing low UV-C doses ranging 0.101–3.06 kJ m-2 at 23°C [60]. It was hard to control P. expansum populations inoculated by wounding than surface contamination evidenced by 3.1 kJ m-2 required for wounded pear disks whereas it was only the half of the dose for intact pear discs for same log reduction [60]. Additionally, even though noticeable changes in texture and appearance were detected soon after treatment, UV treated pear had higher consumer preference compared to untreated after eight weeks of storage.The diversity of production conditions in strawberry and limitation in traditional controlling techniques yield many challenges in controlling diseases, which lead many types of research. Many research show evidence of influencing systemic acquired resistance and activation of phytochemical metabolic pathways in berries by ultraviolet light [24, 26, 35, 61]. Activation of metabolic pathways of phytochemical related systemic resistance in strawberry was investigated by range from 0.25 to 4.00 kJ m-2, and there was a positive relation of ethylene production, phenylalanine ammonia-lyase activity, and a germicidal effect with increasing dose [24]. In another research, 0.43, 2.15 and 4.30 kJ m−2 illuminations had promoted the antioxidant capacity and activity of antioxidant enzymes in strawberry [26]. Moreover, 2.15 and 4.30 kJ m-2 UV-C illumination gave the best decay inhibition of 29.6% and 27.98% respectively. Pombo et al. (2011) also showed the expression of the genes, which were responsible to plant defense and activity of enzymes (phenylalanine ammonia lyase & polyphenol oxidase) were improved in the treated fruit [35]. In later research, 4.1 kJ m-2 UV-C dose applied half side of fruit with inoculated with B. cinerea and rest of strawberry served as control. Even though higher ultraviolet dose extends shelf life, it causes permanent damages on fresh fruit. For instance, dose above 10 kJ m-2 made an adverse effect on the calyx in strawberry [62]. Also in the last research, UV-C dose of 0.5–15.0 kJ m-2 adequately controlled B. cinerea in strawberry, but the similar doses were not significant for managing Monilinia fructigena in sweet cherry [62]. A recent research revealed that influence of a dark period (4 h) after UV treatment for effective controlling B. cinerea disease development [63]. Additionally, no adverse effects of UV-C irradiation on fruit set, yield, and quality were observed even repeating treatment twice a week for seven weeks. Moreover, the research assumption was by maintaining a dark environment after exposure to a germicidal UV-C led to avoid light activation of the DNA repair mechanism in gray mold. Also, by having no light period more likely contributed to decreasing the UV-C dose requirement below 0.02 kJ m-2 [63]. Interestingly, the research showed virulence of the survived conidia reduced noticeably. Sequential application of ultraviolet illumination with other decay control method showed a synergistic effect.Pan et al., (2004) reported, 4.1 kJ m-2 UV-C and 45°C heat treatment, either separately or combined gave better control of fungal infection out of four UV-C doses (1.3, 4.1 & 6.9 kJ m-2) and combined with heat treatment (41, 43, 45°C, 3h) on strawberries [25]. In addition, both the treatments showed influence in color changes and titratable acidity, but neither had an impact on total sugar content. UV-C treatment (5 kJ m-2) alone or combined with chlorine dioxide (ClO2, 50 mg L-1) or fumaric acid (FA; 0.5%) had a significant effect on microbial population [64]. Further, better sensory properties were achieved for combined treatments.If higher intensity UV-C treatment provides similar favorable results as low intensity, treatment time can be reduced, which most likely gives an advantage in the fresh produce industry. An ultraviolet dose of 4 kJ m-2 was provided at 3 or 33 W m-2 intensity levels to strawberries [40]. The results favor on higher intensity, which reduced the decay percentage during storage, and showed greater consumer preference. In another research, the distance between lamps and specimen (tomatoes) were changed to provide different intensities, which applied 16 W m-2 and 6.5 W m-2, for the shortest and longest distances respectively [65]. When samples were exposed to the low intensity (dose in the range of 1.17 to 23.4 kJ m-2), inactivation was minimal or null compared to when tomatoes were closer to the lamps (max dose of 57.6 kJ m-2). Moreover, UV-C was the most influencing treatment method for the color of the produce with compare to Cl, citric acid, and O3 [65]. Another research on MicroTom cherry tomatoes showed lower accumulation of lycopene, β-carotene, lutein + zeaxanthin and δ-tocopherol; whrease retained higher levels of chlorogenic acid, ρ-coumaric acid and quercetin by 3.7 kJ m−2 UV-C illumination [61]. A recent study on tomatoes again revalidated concept of the influence of hormetic dose on eliciting disease resistance, delayed ripening, and surface color changes [66]. One of the drawbacks of industrial adaptation of low-intensity ultraviolet treatment is long treatment time. Moreover, the later study has overcome that bottleneck effect by using high intensity pulsed polychromatic light, and hence treatment time reduced nearly forty folds without suffering outcome.

and phenylalanine ammonia lyase activities were observed after 6 h and reached to the maximum 96 h after ultraviolet light treatment. Sliced pear without peel or fresh cut pear with peel were inoculated with Listeria innocua, Listeria monocytogenes, Escherichia coli, for yeast Zygosaccharomyces bailli, Zygosaccharomyces rouxii, Debaryomyces hansenii, and evaluated for the efficacy of UV-C treatment range from 0 to 87 kJ m-2 [59]. The effectiveness of UV-C was lower for the slices of pear with peels (1.8 - 2.5 log reduction for the cocktail strains) whereas the higher reduction in the range of 2.6 - 3.4 log were observed for without peels [59]. Moreover, while the survival patterns for the different microorganisms had a similar trend, the resistance determined by the type of microorganism and method of slices process. In another research inactivation of Penicillium expansum in cut pears (pear disks) were examined by exposing low UV-C doses ranging 0.101–3.06 kJ m-2 at 23°C [60]. It was hard to control P. expansum populations inoculated by wounding than surface contamination evidenced by 3.1 kJ m-2 required for wounded pear disks whereas it was only the half of the dose for intact pear discs for same log reduction [60]. Additionally, even though noticeable changes in texture and appearance were detected soon after treatment, UV treated pear had higher consumer preference compared to untreated after eight weeks of storage.The diversity of production conditions in strawberry and limitation in traditional controlling techniques yield many challenges in controlling diseases, which lead many types of research. Many research show evidence of influencing systemic acquired resistance and activation of phytochemical metabolic pathways in berries by ultraviolet light [24, 26, 35, 61]. Activation of metabolic pathways of phytochemical related systemic resistance in strawberry was investigated by range from 0.25 to 4.00 kJ m-2, and there was a positive relation of ethylene production, phenylalanine ammonia-lyase activity, and a germicidal effect with increasing dose [24]. In another research, 0.43, 2.15 and 4.30 kJ m−2 illuminations had promoted the antioxidant capacity and activity of antioxidant enzymes in strawberry [26]. Moreover, 2.15 and 4.30 kJ m-2 UV-C illumination gave the best decay inhibition of 29.6% and 27.98% respectively. Pombo et al. (2011) also showed the expression of the genes, which were responsible to plant defense and activity of enzymes (phenylalanine ammonia lyase & polyphenol oxidase) were improved in the treated fruit [35]. In later research, 4.1 kJ m-2 UV-C dose applied half side of fruit with inoculated with B. cinerea and rest of strawberry served as control. Even though higher ultraviolet dose extends shelf life, it causes permanent damages on fresh fruit. For instance, dose above 10 kJ m-2 made an adverse effect on the calyx in strawberry [62]. Also in the last research, UV-C dose of 0.5–15.0 kJ m-2 adequately controlled B. cinerea in strawberry, but the similar doses were not significant for managing Monilinia fructigena in sweet cherry [62]. A recent research revealed that influence of a dark period (4 h) after UV treatment for effective controlling B. cinerea disease development [63]. Additionally, no adverse effects of UV-C irradiation on fruit set, yield, and quality were observed even repeating treatment twice a week for seven weeks. Moreover, the research assumption was by maintaining a dark environment after exposure to a germicidal UV-C led to avoid light activation of the DNA repair mechanism in gray mold. Also, by having no light period more likely contributed to decreasing the UV-C dose requirement below 0.02 kJ m-2 [63]. Interestingly, the research showed virulence of the survived conidia reduced noticeably. Sequential application of ultraviolet illumination with other decay control method showed a synergistic effect.Pan et al., (2004) reported, 4.1 kJ m-2 UV-C and 45°C heat treatment, either separately or combined gave better control of fungal infection out of four UV-C doses (1.3, 4.1 & 6.9 kJ m-2) and combined with heat treatment (41, 43, 45°C, 3h) on strawberries [25]. In addition, both the treatments showed influence in color changes and titratable acidity, but neither had an impact on total sugar content. UV-C treatment (5 kJ m-2) alone or combined with chlorine dioxide (ClO2, 50 mg L-1) or fumaric acid (FA; 0.5%) had a significant effect on microbial population [64]. Further, better sensory properties were achieved for combined treatments.If higher intensity UV-C treatment provides similar favorable results as low intensity, treatment time can be reduced, which most likely gives an advantage in the fresh produce industry. An ultraviolet dose of 4 kJ m-2 was provided at 3 or 33 W m-2 intensity levels to strawberries [40]. The results favor on higher intensity, which reduced the decay percentage during storage, and showed greater consumer preference. In another research, the distance between lamps and specimen (tomatoes) were changed to provide different intensities, which applied 16 W m-2 and 6.5 W m-2, for the shortest and longest distances respectively [65]. When samples were exposed to the low intensity (dose in the range of 1.17 to 23.4 kJ m-2), inactivation was minimal or null compared to when tomatoes were closer to the lamps (max dose of 57.6 kJ m-2). Moreover, UV-C was the most influencing treatment method for the color of the produce with compare to Cl, citric acid, and O3 [65]. Another research on MicroTom cherry tomatoes showed lower accumulation of lycopene, β-carotene, lutein + zeaxanthin and δ-tocopherol; whrease retained higher levels of chlorogenic acid, ρ-coumaric acid and quercetin by 3.7 kJ m−2 UV-C illumination [61]. A recent study on tomatoes again revalidated concept of the influence of hormetic dose on eliciting disease resistance, delayed ripening, and surface color changes [66]. One of the drawbacks of industrial adaptation of low-intensity ultraviolet treatment is long treatment time. Moreover, the later study has overcome that bottleneck effect by using high intensity pulsed polychromatic light, and hence treatment time reduced nearly forty folds without suffering outcome. 4. UV studies on Blueberry

- Perkins-Veazie et al., (2008) reported ripe rot on berries decreased by 10% in UV-C treatment, higher UV dosage (more than 8 kJ m-2) influenced on decaying [27]. Also, hormersis was reported as 2 kJ m-2 at only tested intensity of 21.2 W m-2. Moreover, postharvest UV-C treatment on blueberry was effective in stimulating the antioxidant content [27]. However, their study did not provide any conclusive evidence of shelf life enhancement due to UV treatment as blueberries were only kept nine days, and only ripe rot incidence was reported. After the research by Perkins-Veazie et al.,(2008), other blueberry UV treatment studies were carried out to address two research questions; 1) How long might extend shelf life of Blueberries [67, 68] and 2) Phytochemical enhancement and antioxidant level increment due to UV treatment [69]. Erkan et al. (2013) and Nguyen et al. (2014) tried to provide more evidence to explore both the research question in their studies using “Bluecrop” and “Duke” highbush berries separately [67, 68].Entire UV spectrum range (UV-A, -B, and –C) was evaluated separately on blueberry quality and shelf life and following significant information was contributed to blueberry research [68]. Post-harvest UV treatment helped to reduce weight loss and decay of berries. UV-B and -C treatments showed more benefits on the phytochemical formation, antioxidant capacity, and the storability than UV-A illumination.Overall, fewer effects on soluble solids, pH, and titratable acidity were reported by UV-C treatment [70].

5. Conclusions

- Other than its inherent germicidal effect, optimal UV-C dose, that varies with the fruit type, has revealed to promote disease resistance against a wide range of pathogens. It is most likely achieved through initiating systemic acquired resistance, accumulation of phytoalexin, and delayed physiological process related to ripening. Most importantly, higher consumer preference gained in favor of ultraviolet treated fruits among the other postharvest treatments brings better opportunity for the application of ultraviolet technology to grow in fresh produce industry.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- The authors acknowledge the partial funding support from the specialty crop grant program of the USDA-AMS contracted through the Illinois Department of Agriculture.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML