-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Food Science and Nutrition Engineering

p-ISSN: 2166-5168 e-ISSN: 2166-5192

2015; 5(2): 82-87

doi:10.5923/j.food.20150502.02

Assessment of Knowledge and Practices on Complementary Food Preparation and Child Feeding at Shebedino, Sidama Zone, Southern Ethiopia

Beruk Berhanu, Kebede Abegaz, Esayas Kinfe

School of Nutrition, Food Science and Technology, Hawassa University, Hawassa, Ethiopia

Correspondence to: Beruk Berhanu, School of Nutrition, Food Science and Technology, Hawassa University, Hawassa, Ethiopia.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2015 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

Under-nutrition is the common child malnutrition problem in Ethiopia. In this study the knowledge and practices of mothers on complementary food (CF) preparation, blending, traditional processing techniques and child feeding at Shebedino, Sidama, Ethiopia were assessed. Fifty six (56) mothers who had 6-24 month old children and living at Remeda and Teremesa kebeles (smallest administrative unit) were purposively selected for this study using semi-structured questionnaire. Agricultural production and/or availability of cereals, root crops, legumes, fruits and vegetables were assessed. Two focus group discussions were also conducted with mothers and experts group. The result revealed that all the mothers use maize and 75% use both maize and enset for preparation of complementary food. Only 8.9% use legumes for CF preparation. All the mothers prepare CF in the form of porridge and 75% prepare bread in addition to the porridge. Around 80.4% prepare the CF as normal family food. Soaking and germination of raw materials were not common. Boiling, roasting and fermentation were applied by all mothers for CF preparation. About 91.1% of the mothers started complementary feeding for their children at the age of six months and their major reason was the presence of health education (82.1%) at both kebeles. The first rank (76.8 %) of criteria for adoption and preparation of nutritionally improved CF was the cost. Around 98.2% of the mothers don’t use commercial infant formula. About 57.1% have income of Birr 200 to 500. In conclusion, knowledge and practice gap on CF preparation, blending and traditional processing techniques was observed despite production and availability of crops, fruits and vegetables. This gap was related with economic problem.

Keywords: Malnutrition, Complementary food preparation, Blended staple porridge, Child feeding

Cite this paper: Beruk Berhanu, Kebede Abegaz, Esayas Kinfe, Assessment of Knowledge and Practices on Complementary Food Preparation and Child Feeding at Shebedino, Sidama Zone, Southern Ethiopia, International Journal of Food Science and Nutrition Engineering, Vol. 5 No. 2, 2015, pp. 82-87. doi: 10.5923/j.food.20150502.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Malnutrition in children results in growth retardation and limited intellectual abilities that diminish their working capacity during adulthood, decreased resistance to disease and infections and ultimately ill health and death. It delays motor and mental development, exposes to frequent attack of diarrheal disease; most importantly it can interfere with attainment of full human potential [4]. In Ethiopia the most common forms of malnutrition is protein-energy malnutrition (PEM), vitamin A deficiency, iodine deficiency disorders, and iron deficiency anemia [5, 14]. According to Ethiopian central statistics authority (CSA) report in 2012, the prevalence of stunting in under five years old Ethiopian children is 44%, where 21% are severely stunted, 29% underweight and 10% wasted. The prevalence of anemia in the age group of 6 to 59 months of children is 44%. In southern Ethiopia, the prevalence of stunting, underweight and wasting were 44.1%, 28.3% and 7.6% respectively. Inadequate complementary food (CF) is a major cause for the high incidence of child malnutrition. The weaning period is the most critical period in a child’s life as infants transfer from nutritious and uncontaminated breast milk to the regular family diet with chance of vulnerable to malnutrition and disease. Traditional CF made of cereals and legume may be low in several nutrients including protein, vitamin A, zinc and iron. Furthermore, the bulkiness of traditional CF, the high cost and inadequacy in production of protein-rich foods, high concentrations of fiber, anti-nutrients and inhibitors are the major factors in reducing their nutritional benefits [21]. Feeding practice such as time of CF introduction, type of CF including its quality and quantity have been identified as some of the most important factors for the child’s nutritional status. Moreover, various food processing techniques have the potential to enhance the nutrient bioavailability, palatability and convenience of supplement foods suitable for CF preparation including roasting, germination, milling, baking, drying, fermentation and extrusion [21]. Hence, the objective of this study was to assess the knowledge and practices of mothers at Shebedino, Sidama, Ethiopia on CF preparation, blending, processing techniques and child feeding.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Description of the Study Area

- The study was conducted from June 1 to July 30, 2012 at Shebedino, Sidama zone, which is located 27 km from Hawassa, and 302 km from Addis Ababa, the capital of Ethiopia. According to Ethiopian CSA report in 2012, the total population of the district was 269,529. Among them, 136,057 were males and 133,472 are females. The district consists of 35 kebeles comprising of 51,044 residential houses with an average household family size of 5. The district is known for growing enset, chat, maize, barley, wheat, teff, Irish potato, sweet potato, banana, avocado and broad bean [5].

2.2. Sampling of the Study Population

- Based on the information gathered from Shebedino agriculture office, the district has two farm trial sites in Teremesa and Remeda kebeles where new technologies are tested on. Farmers of these two kebeles are known for early adoption of new technologies and growing diversified cereals like maize and teff, root crops like enset, irish potato and sweet potato, legumes like chickpea, fruits and vegetables. Based on these facts, the two kebeles were purposively selected for this survey. Mothers who had 6-24 months children, live in either of the two kebeles and willing to participate in the survey were included in the study. Fifty six mothers-child pairs were purposively selected for the survey using semi-structured questionnaire. Eight mothers were randomly selected from the fifty six mothers for the first focus group discussion. Maternal and child health expert, agricultural production expert, food security expert, development agent and health extension worker from Shebedino agriculture and health offices were randomly selected for the second focus group discussion. A total of eight people were included in the second focus group discussion.

2.3. Data Collection

- A semi-structured questionnaire and semi-structured focus group discussion guide were used for survey and focus group discussion respectively. Both the questionnaire and focus group discussion guide were first developed in English and later translated to Amharic and local Sidamigna languages. Pre-test of the survey questionnaire was made on 10 mothers from the two kebeles. Based on the pre-test all the ambiguous words were removed and suggestions were incorporated. The focus group discussion was intended to get in-depth information on local CF preparation, processing, composition and child feeding practices.Variables like socio-demographic and economic characteristics of the study participants, agricultural production and availability of crops in local market, CF processing techniques from staple produces, and CF preparation, composition and child feeding practices were assessed. Letter of ethical approval was obtained from Hawassa University Ethical Clearance approval Committee. Study participants were asked for their willingness to participate in the study and verbal consent form was filled.

2.4. Data Analysis

- The data were entered, cleaned and analyzed using SPSS statistical software version 19.0. Descriptive statistics (frequency and percentage) were used to present counts, proportions and averages.

3. Results

3.1. Socio-Demographic and Economic Characteristics of the Study Participants

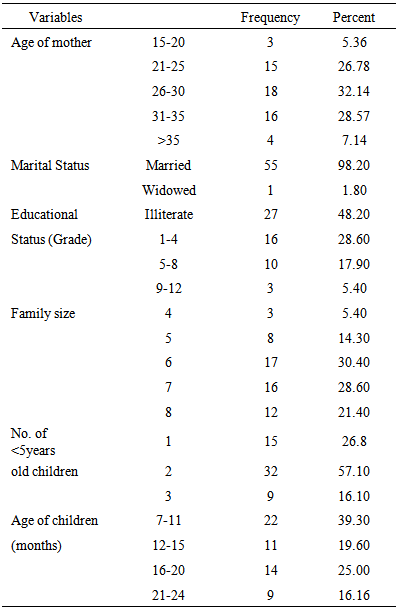

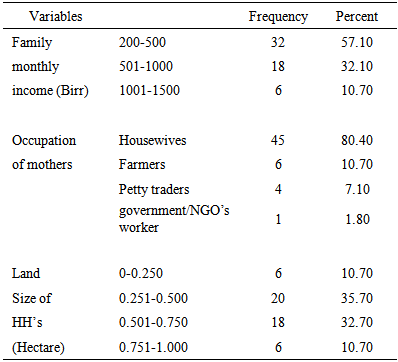

- The numbers of mother-child pairs participated in this study were fifty six with response rate of 100%. Around 27 (48.2%) were from Remeda kebele while 29 (51.8%) were from Teresema kebele of Shebedino. Around 30.4% and 57.1% households had six family sizes and two under five year old children respectively. Most of the respondents were married (98.2%) and 48.2% of mothers did not attend formal education. Among the children and mothers participated in this study, 39.3% were in the age range of 7 to 11 months and 60.7% were in the age range between 26 and 35 years old. The mean family size of respondents was 6.42 with range of 4 to 8 and half of the respondents had 4 to 6 family sizes (Table 1). The monthly income of most study households (57.1%) was Birr 200-500. The proportion of households who were reported to have 0.25 to 0.50 hectares was 35.7%. The high proportions of mothers (80.4%) were housewives (Table 2).

|

|

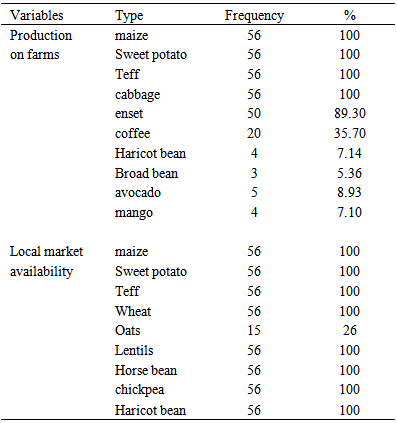

3.2. Agricultural Production and Availability of Crops in Local Market

- Agricultural production and availability of crops at Shebedino local market is presented in Table 3. All of the study households grew maize, sweet potato, teff and local cabbage. Less number of households 4 (7.14%), 3 (5.36%) and 5 (8.93%) were found to grow haricot bean, broad bean and avocado respectively in their farms. Crops like maize, teff, wheat, barley, oats, sweet potato, chickpea, lentils, horse bean, haricot bean, broad bean can also be accessed from local market.

|

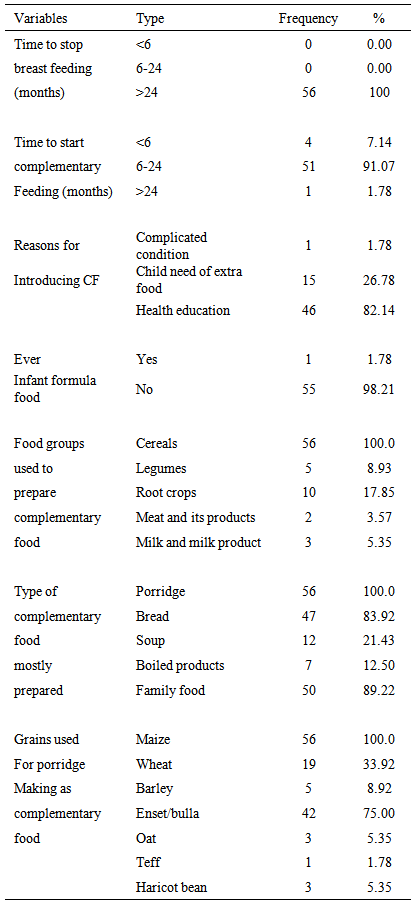

3.3. Complementary Food Preparation, Processing and Child Feeding Practices

- As shown in Table 4, mothers (91.1%) started feeding complementary food to their children at the age of six months. The main reason for introduction of complementary food for their children was health education provided at the kebeles which accounted for 82.1%. Around 98.2% mothers did not give infant formula for their children (Table 4).

|

4. Discussions

- Appropriate complementary feeding promotes growth and prevents stunting among children between 6 and 24 months of age. Inadequate knowledge about complementary food preparation and child feeding practices is often one of the greater determinants of malnutrition [13]. In this study, 32.1% of the mothers were in the range of 26-35 years old. This result is in agreement with a report (32.1%) from Northern Ethiopia [22]. But, it is higher than study conducted in south west Ethiopia (3.6%) [23]. According to [7], higher number of stunted children (77.6%) and underweight children (71.4%) were observed with mothers aged 20-30 years old in Ethiopia and this may be due to poor socioeconomic conditions of the family and poor caring practices of their children. The results of this study showed more than 95% of mothers were married, which is consistent with study conducted in Gurage, Sidama and Jimma south and south west Ethiopia [9, 19, 3]. The present study revealed that 5.4% of mothers attended or completed secondary school which is similar to the Ethiopian CSA report [5]. The proportion of illiteracy on the present study was 48.2% which is in line with a report in Gondar (47.8%) [15]. In all regions of Ethiopia, illiteracy of mothers (care givers) contributed to higher score of underweight (37.3 %), wasting (13.1 %) and stunting (41.5%) in children aged 6-59 months old [7]. This may be due to knowledge gap on appropriate maternal and child nutrition by mothers. In the present study 21.4% of households had family members greater than seven which is similar with study conducted in Sidama zone which is 22.1%. Around 44.7% of households contained five to six family members which is comparable with finding in Silte, southern Ethiopia which was 41.6% [17]. This higher number of family size in the study households may favor the presence of food and nutrition insecurity. In the present study, 80.4% of mothers were housewives. Comparable findings were observed in the study conducted at Gurage (82.8%) and Sidama zone (75.5%) [2, 3]. In case of land holding size, 46.4% of families owned 0 to 0.5 hectare land in this study. According to [3], lower number of mothers was housewives (75.5%) which had high association with childhood illness and may favor child to malnutrition. The family income per month of this study within range of 500 to 1000 Ethiopian birr was 32.1% which is similar finding in study conducted in Tigray (31.3%) [22]. Ethiopian food consumption patterns vary from one region to another depending on differences in agricultural production, ethnic, cultural and religious backgrounds. A range of crops are either grown or accessed in the study area including fruits and vegetables. However, the production of legumes and fruits are lower than cereals and root crops. Maize is the staple food in Kaffa, Illuababora and Sidama, in the South-west and southern part of the country, but fruits and vegetables are not commonly consumed in rural area which is in line with result of the study [8]. Among traditional processing methods roasting, boiling and fermentation were common used to prepare family foods like roasted and boiled grains and kocho/enset. In this study, only 1.78% of mothers gave formula food for their children, which has more or less same result with Ethiopian CSA report and finding in Tigray region of Ethiopia [5, 24]. This may be due to the lower purchasing power of rural peoples, ever increasing cost of infant formula and poor availability [1]. Higher number of children in this study started complementary feeding at the age of six months 51 (91.07%). This may be due to the recent provision of health education by health extension workers which covered 82.1% among the reasons for introduction of CF at Shebedino. In this study cereals and root crops were the main food groups for preparation of CF, which is comparable with previous finding in developing countries [1, 12]. In the present study, all households prepared complementary food in the form of porridge, which is similar with complementary recipes developed for Ethiopian children by ministry of health of Ethiopia [13]. Maize and enset/bulla were the dominant crops that the families used to prepare porridge at Shebedinao which is similar with FAO report on Ethiopian nutrition profile [8]. In this study mothers were interested to accept new CF that is important for health and growth of their children they also mainly agreed on low cost and easy of processing which is supported by kocho based complementary food and technical update on complementary feeding of young children in developing countries [1, 6].

5. Conclusions

- A range of cereals, legumes, fruits and vegetables are grown and/or accessible in the market. Maize and enset/bulla are the main food items used for preparation of complementary foods in the form of thin porridge. Health/nutrition education has great impact on mothers to start complementary foods at age of six months. Roasting, fermentation and boiling are used to prepare family foods and local beverages in the study area. Mothers have limited knowledge on the benefits and preparation techniques on complementary foods. However, they are willing to accept technology for nutritionally improved complementary food preparation as far as it is less costly and easy to process. Therefore, improved technology on CF formulation and preparation can be a research area to strengthen the health/nutrition education to be given to mothers. The CF improvement project need to address the issues of on less costly, easy to process and nutritionally improved complementary food processing from cereals, legumes, animal products, fruits and vegetables at Shebedino.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

- The authors would like to acknowledge the American people through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) for their financial support under Agreement No. AID-663-A-11-00017 and Hawassa University, NORAD project for funding this research. The authors would like also to forward participants who involved in this research.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML