-

Paper Information

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Food Science and Nutrition Engineering

p-ISSN: 2166-5168 e-ISSN: 2166-5192

2015; 5(1): 68-73

doi:10.5923/j.food.20150501.09

Characteristics and Micronutrient Intakes of Exclusively and Non - Exclusively Breastfeeding Mothers in Imo State of Nigeria

Olaitan I. N.1, Onimawo I. A.2, Nkwoala C. C.3

1University of Agriculture Makurdi, Benue State, Nigeria

2Ambrose Alli University Ekpoma, Edo State, Nigeria

3Michael Okpara University of Agric. Umudike, Abia State, Nigeria

Correspondence to: Olaitan I. N., University of Agriculture Makurdi, Benue State, Nigeria.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2015 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

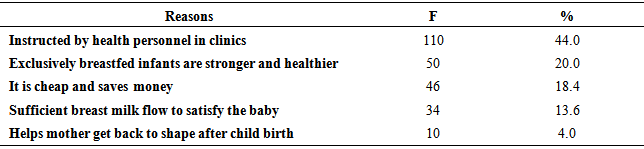

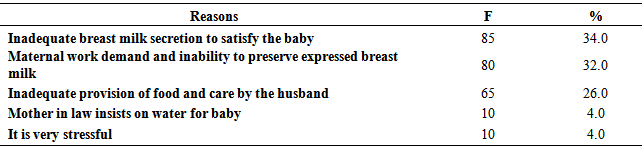

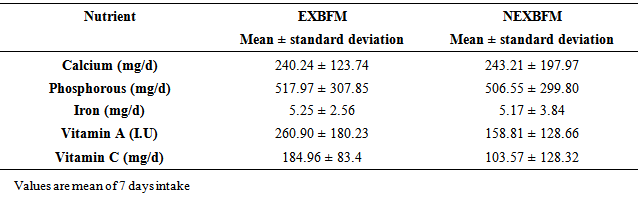

The characteristics and micronutrient intake of breastfeeding mothers were assessed in this study. Five hundred (500) breastfeeding mothers comprising 250 exclusively breastfeeding mothers (EXBFM) and 250 non - exclusively breastfeeding mothers (NEXBFM) randomly selected from three Local Government Areas (Owerri North, Obowo and Ohaji-Egbema) in Imo state Nigeria were used for the study. The characteristics of the respondents were obtained using a questionnaire. The micronutrient contents of foods consumed by the respondents were obtained through chemical analysis of duplicate food samples while weighed food inventory was used to determine the portion sizes consumed. The result showed that 76% (380 out of 500) of the breastfeeding mothers were in the age ranges of 26 to 35 years of which 51% were exclusively breastfeeding their infants while more than half (58%) of the mothers aged between 18 and 25 years (n = 78) were not exclusively breastfeeding their infants. About 72% (358/500) of the infants studied were 9 – 16 weeks (2 – 4 months) and most (53%) of these infants were exclusively breastfed however (60%) of infants aged 2 – 8 weeks (<2 months) were not exclusively breastfed. Most (44.0%) of the mothers who were exclusively breastfeeding their infants were instructed to do so by the health personnel in the clinics and the economic benefits of exclusive breastfeeding motivated 18.4% of the mothers to exclusively breastfeed their babies. However, insufficient milk secretion was the reason given by 34% of the breastfeeding mothers for not practicing exclusive breastfeeding. Maternal work demands coupled with inability to preserve expressed breast milk were the reasons given by 32% of the breastfeeding mothers for not breastfeeding exclusively, while 26% of them indicated that inadequate provision of food and care by their husbands were their reasons for not being able to breastfeed exclusively. Only 4% reported that exclusive breastfeeding was stressful. Except for vitamin C (184.96mg/d for EXBFM and 103.57mg/d for NEXBFM), none of the nutrient intakes by the breastfeeding mothers were up to 50% of recommended intakes for lactating women. Vitamin A intake (260.90 µg/d EXBFM; 158.81.µg/d NEXBFM) and calcium intake (240.24mg/d EXBFM; 243.21mg/d NEXBFM) ranked the lowest in meeting the recommendations.

Keywords: Lactation, Exclusive breastfeeding, Characteristics, Micronutrient intake

Cite this paper: Olaitan I. N., Onimawo I. A., Nkwoala C. C., Characteristics and Micronutrient Intakes of Exclusively and Non - Exclusively Breastfeeding Mothers in Imo State of Nigeria, International Journal of Food Science and Nutrition Engineering, Vol. 5 No. 1, 2015, pp. 68-73. doi: 10.5923/j.food.20150501.09.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Lactation naturally follows pregnancy as the mothers’ body continues to nourish the infant [1] Lactation requires both an increased supply of nutrients to the lactating mother and the development of mechanics that ensure the preferential use of the nutrients by the mammary glands [2] Ideally, the mother who chooses to breastfeed her infant will continue to eat nutrient dense foods throughout lactation. An adequate diet is needed to support the stamina, patience and self confidence that nursing an infant demands. However, when vitamin intake is inadequate, the vitamin content of breast milk can diminish which puts the infant at risk of deficiency [3]. This occurs mostly when the mother did not have adequate stores before and during pregnancy. The adequacy of vitamin A in the human milk has been reported to be highly dependent upon maternal diet and nutritional status [4]. Breastfeeding is a traditional norm in most African countries including Nigeria and is widely practiced. However breastfeeding practices are far from optimal [5]. In order to obtain the optimum benefits of breastfeeding for the infant and mother, the Innocenti Declaration recommended that all women should be enabled to practice exclusive breastfeeding and all infants should be fed exclusively on breast milk from birth to about 6 months of age [2]. In spite of this declaration exclusive breastfeeding at 6 months is not a common practice in developed countries and appears to be rarer in developing countries [5], [4] including Nigeria [6]. In addition, [4] identified that socio economic, cultural and biological implications in practicing exclusive breastfeeding have rarely been researched into.The present study therefore examined the extent of practice and reasons for not practicing exclusive breastfeeding. The micronutrient intakes of the exclusively breastfeeding mother were compared with those of non exclusive breastfeeding mothers and with recommended intakes. The information provided is aimed at enlightening all stake holders in infant and maternal health on some impediments to the attainment of exclusive breastfeeding and optimum nutritional status of breastfeeding mothers. The study further aimed at identifying factors that influence the choice of mothers to either exclusively breast feed or not exclusively breast feed their babies and also to compare the mothers’ micronutrient intake as compared to the recommended intake.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sampling

- Five hundred (500) breastfeeding mothers comprising 250 exclusively breastfeeding mothers (EXBFM) and 250 non - exclusively breastfeeding mothers (NEXBFM) were used for the study. The samples were randomly selected from mothers who were attending maternity child health care centers and the hospitals that operated infant welfare clinics in the three Local Government Areas representing the three geopolitical zones in Imo state: Owerri North (167: 84 EXBFM, 83 NEXBFM), Obowo (167: 83 EXBFM, 84 NEXBFM) and Ohaji Egbema (166: 83 EXBFM, 83 NEXBFM).

2.2. Characteristics of Mother and Infant

- A well structured and validated questionnaire was used to obtain information on mothers’ age, age of infant being breastfed and reasons for practicing exclusive or non – exclusive breastfeeding.

2.3. Nutrient Intake Assessment

- A prospective method was used to assess the nutrient intakes of the breastfeeding mothers. Chemical analysis of duplicate food samples, as described by [7] was used to determine the calcium, phosphorous, iron, vitamin C (ascorbic acid) and vitamin A contents of the prepared foods. The monotonous nature of the diet made it easier for the estimation. Calcium content was determined using the Potassium permanganate (KMnO4) method, phosphorous by molybdate method while iron was determined by atomic absorption spectrophotometer. Vitamin C was determined by titration with 2, 6 – dichlorophenol indophenols solution while vitamin A was determined as retinol (preformed vitamin A) for foods of animal origin and β-carotene (provitamin A) for foods of plant origin [8]. The vitamin A activity of β-carotene was estimated to be 1/6 of preformed vitamin A [9].A 7-day weighed food method was used to determine the portion size consumed by the subjects. Plate waste was subtracted from the weight of the food to determine the actual weight of food consumed. Nutrient intake was as: weight of food consumed (gram) x nutrient content of food (per gram). The average was calculated to obtain daily intake [10].

3. Results

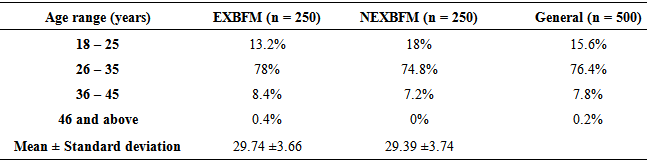

- The results shown in Table 1. indicated no significant difference (p > 0.05) in the percentage of exclusive breastfeeding mothers (78%) and non- breastfeeding mothers (74.8%) that were within the age ranges of 26 to 35 years. The 8.4% of mothers within the aged range of 36 to 45 years practiced exclusive breastfeeding while (7.2%) could not. However, among the breastfeeding mothers within the age range of 18 and 25 years, 18% could not breastfeed their infants exclusively while 13.2% did.

|

|

|

|

|

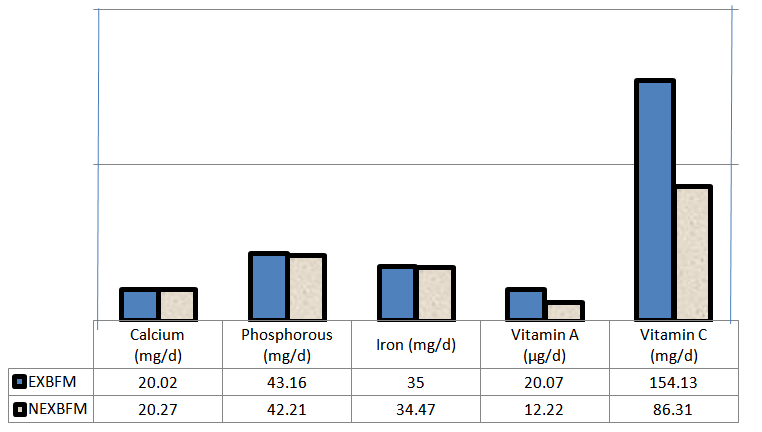

| Figure 1. Percentage of FAO/WHO (2002) recommended nutrient intake |

4. Discussion

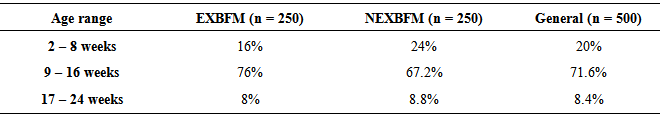

- The study (Table 1) revealed that most young breastfeeding mothers (18 to 25 years) were not exclusively breastfeeding their infants as compared to older breastfeeding mothers (above 26 years). This may be attributed to ignorance and possible complications during delivery as it is expected that the breastfed infant may be their first baby. However, majority of the mothers studied were within the age range of 26 and 35 years. The results revealed that early marriage (<18 years) was uncommon and not encouraged in Imo State (a south eastern state in Nigeria). This could be attributed to the high rate of formal education among the females in that area.The findings in this study (Table 2) confirmed report that exclusive breastfeeding declines precipitously in the first month of life [5]. Some, (24%) infants in Imo State, Nigeria were not exclusively breastfed in the first eight weeks of life. It was also evident that exclusive breastfeeding was not generally practiced for up to 17 – 24 weeks No evidence has confirmed an advantage to starting complementary foods before 6 months [11].The adoption of exclusive breastfeeding by most (44%) breastfeeding mothers as instructed by health personnel in the clinics (Table 3) may be attributed to the massive campaign of exclusive breastfeeding through the “Baby Friendly Hospital Initiative” in the country. In Cuba, exclusive breastfeeding tripled in six years from 25% to 75% with the introduction of Baby Friendly Hospital Initiative [12]. Mothers who secrete sufficient breast milk (13.6%) were more confident in adopting exclusive breastfeeding (Table 3). On the other hand insufficient breast milk secretion discouraged most mothers (34%) from exclusively breastfeeding their infants in this study. The complaint of insufficient breast milk secretion has been seen to be reoccurring in literature [13], [14], and [15]. However [16] suggested that optimal milk production can be achieved by frequent exclusive breastfeeding in the early weeks of lactation. Findings in this study (Table 4) confirmed the report by [4], [17], [18] and [19] that times like famine and maternal work demand can cause mothers not to exclusively breastfeed their infant especially with very early return to work (when the child is <24 weeks old). A study in Accra Ghana identified that majority (81.4%) of the mothers who breastfed their infants exclusively attributed it to help by their husbands [20]. This attribute was identified in this study as 26% of the mothers who did not breastfeed exclusively attributed it to inadequate provision of food and care by their husbands (Table 4). When a mother is well nourished, it helps her to breastfeed while maintaining her own body stores. Furthermore exclusive breastfeeding especially as it concerns not giving the infant water is still hardly accepted in most African cultures. This view was confirmed by 4% of the non- exclusive breastfeeding mothers in this study (Table 4) who reported that their mother- in- laws insisted on giving the infants water because it is a traditional norm during lactation. Other investigators have reported that some believed that the baby will be dehydrated when given only breast milk [21] while some parent–in-laws felt the child will grow to be “dry hearted” or wicked if not given water [22]. Furthermore the results in Table 4 indicated that 4% of the mothers believed that exclusive breastfeeding was stressful. This agreed with the report of other investigators [23] and [24] that some breastfeeding mothers felt exclusive breastfeeding is energy sapping and stressful.The mean intake of some nutrients (phosphorous, vitamin A and vitamin C) by exclusively breastfeeding mothers (517.97±307.85mg/d, 260.90±180.23ug/d and 184.96±83.4mg/d respectively) were significantly higher (P<0.05) than those of non-exclusively breastfeeding mothers (506.55±299.80mg/d, 158.81±128,66µg/d and 103.57±128.32mg/d respectively) (Table 5), which may be due to better food provision by husbands. However, none of the exclusive and non-exclusive breastfeeding mothers met up to 50% of the [9] recommended intakes for all but one (vitamin C) of the nutrients (Figure 1). Apart from vitamin A content of human milk which has been found to be highly dependent on maternal diet and nutritional status [4], nutrient inadequacies, in general have been reported to reduce the quantity, not the quality of breast milk. Breastfeeding mothers do need an increased number of calories and nutrients to maintain their milk flow [25]. Nutrients, such as calcium in human milk, have been found to be fairly constant throughout lactation and are not influenced by maternal diet [4]. The iron endowment at birth meets the iron needs of the breastfed infant in the first half of infancy i.e. 0 to 6 months, consequently the impact of nutrient deficiencies identified in this study may not be expressed in the breastfed infant especially if the infant is breastfed more often, on demand and exclusively. Nevertheless, when maternal diet is inadequate, the mothers own nutritional status will suffer [26] hence mothers should be encouraged to eat adequately in order to absorb the needed nutrients in their diets to replace maternal losses.

5. Conclusions

- This study identified that most young breastfeeding mothers did not practice exclusive breastfeeding as compared to the older mothers. Majority of the infants studied were 9 – 16 weeks (2 – 4 months) and most of these infants were exclusively breastfed. Instructions by health personnel and secretion of sufficient breast milk were the major factors that motivated the breastfeeding mothers to feed their infants exclusively on breast milk. On the other hand, insufficient secretion of breast milk, maternal work demand and inadequate provision of food and care by husbands discouraged the breastfeeding mothers from practicing exclusive breastfeeding in this study. In general, however the micronutrient intakes of the breastfeeding mothers were highly inadequate. Lactation requires both an increased supply of nutrients to the lactating mother, and there is the need to create enabling socio cultural environment that will encourage exclusive breastfeeding.

6. Recommendations

- While promoting exclusive breastfeeding through various government and non governmental agencies, there is need to embark on enlightenment campaigns targeted at significant others in infant breastfeeding such as the men and mother in laws on composition of breast milk and the need to encourage the lactating mother to breastfeed exclusively. Intervention programmes should be initiated before delivery to motivate the pregnant mother make decisions on ways to successfully and exclusively breastfeed her infant, and be resolute in the practice despite negative influences and constraints. Breastfeeding mothers should also be encouraged to allow the infant suckle the breast more frequently to promote flow of breast milk sufficient for the baby and educated on safe and hygienic methods of expressing and preserving their breast milk. However, further research to identify various factors that can influence flow of breast milk is highly recommended.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML