Emanuel Peter1, Kijakazi O. Mashoto1, Susan F. Rumisha2, Hamisi M. Malebo3, Angela Shija1, Ndekya Oriyo1

1Health system and Policy Research, National Institute for Medical Research, 2448, Ocean Road, P.O.BOX 9653, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania

2Disease Surveillance and GIS, National Institute for Medical Research, 2448, Ocean Road, P.O.BOX 9653, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania

3Department of Traditional Medicine Research, National Institute for Medical Research, P.O. Box 9653, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania

Correspondence to: Emanuel Peter, Health system and Policy Research, National Institute for Medical Research, 2448, Ocean Road, P.O.BOX 9653, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2014 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

Abstract

The main purpose of this study was to optimize extraction conditions for ferrous (iron II) and L-ascorbic acid from dried calyces of Hibiscus sabdariffa L grown in Dodoma in Tanzania by using Response Surface Methodology (RSM). Plant materials were taxonomically identified and authenticated by a plant taxonomist whereby a voucher specimen number 4992 was deposited at the herbarium in the Department of Botany at the University of Dar es Salaam. RSM with five level three-factor central composite rotatable design (CCRD) was employed to determine optimal combination of independent factors- soaking time, extraction temperature and solid-solvent ratio. Both single and multiple factor experiments were conducted. In single factor experiment (SFE) each independent factor was assessed to give experimental range. Ferrous was estimated by atomic absorption spectrophotometric method (AAS) while L-ascorbic acid was measured by iodometric titration technique. Data were analyzed using SPSS Version 16.0 and Design-Expert software Version 8.0.7.1. Mean and standard deviation of triplicates were calculated and assessed. One way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was also performed to find differences between the effect of the factors and their interaction. Significance was considered at 5% level of confidence (i.e. P<0.05). Finally, the obtained data was fitted using a cubic order polynomial model. The optimized extraction parameters were determined at soaking time 48 minutes, solid-solvent ratio 44% and extraction temperature 55°C. Under these extraction conditions, amount of L-ascorbic acid and ferrous extracted were 83.1 and 7.8 mg/100g respectively. The RSM helped to study interaction effect of extraction temperature, soaking time and solid-solvent ratio. Industries may adopt these optimal extraction conditions for production of Rosella beverages.

Keywords:

Response surface methodology, Hibiscus sabdariffa L, Iron, Ascorbic acid, Extraction conditions

Cite this paper: Emanuel Peter, Kijakazi O. Mashoto, Susan F. Rumisha, Hamisi M. Malebo, Angela Shija, Ndekya Oriyo, Iron and Ascorbic Acid Content in Hibiscus sabdariffa Calyces in Tanzania: Modeling and Optimization of Extraction Conditions, International Journal of Food Science and Nutrition Engineering, Vol. 4 No. 2, 2014, pp. 27-35. doi: 10.5923/j.food.20140402.01.

1. Introduction

Hibiscus sabdariffa L. (Roselle) is an annual herbaceous shrub of the family Malvaceae. It has red calyces which are formed as the flowers fall off [1]. Originally from Angola, it is now cultivated throughout tropical and subtropical regions, especially in Sudan, Egypt, Thailand, Mexico, China, Tanzania, Senegal, Mali and Jamaica for both international market and domestic use [1,2]. Roselle is a drought tolerant, relatively easy to grow, and can be grown as part of multi-cropping system [1]. In Tanzania Roselle is cultivated mainly in the central and some of coastal regions. Analysis of aqueous extract of dried roselle calyces revealed many chemical constituents. Among the identified constituents are alkaloids, L-ascorbic acid, citric acid, anisaldehyde, anthocyanin, β-carotene, β-sitosterol, cyanidin-3-rutinoside, delphinidin, galactose, gossypetin, hibiscetin, mucopolysaccharide, pectin, protocatechuic acid, polysaccharide, quercetin, stearic acid and wax [3–6]. It also rich in minerals such as calcium, magnesium, iron, potassium, sodium and zinc [7–9]. The chemical and mineral composition of dried roselle calyces could suggest its potential for both medicinal and nutritious value.The aqueous extract of dried calyces of H. sabdariffa, has been taken in many parts of the world for the treatment of various medical conditions. Previous clinical studies highlighted that, the extract has significant effect in controlling hypertension, liver diseases, fever, hyperlipidaemia and type-2 diabetes [8,10–14].In Tanzania, the use of roselle calyces has taken importance for the variety of its nutritious and medicinal values. Individuals especially women, soak these calyces and drink the resulting juice. The practice may have been attributable to a claim that roselle juice could correct iron deficiency anaemia. Although mineral and chemical compositions of dried roselle calyces support this claim, studies on extraction of these components are lacking. Factors that influence extraction efficiency have been established. These include extraction methods, particle size, solvent type, solvent concentration, solvent-to-solid ratio, extraction temperature, extraction time and pH [15–17]. To optimize extraction efficiency and contribute to nutritional benefits of roselle, it is important to ascertain the influence of the identified factors. Therefore, this study is designed to determine the mineral and chemical components of roselle grown in Tanzania as well as influence of extraction conditions on yield of L-ascorbic acid and ferrous from dried roselle calyces and optimize these conditions using Response Surface Methodology (RSM).

2. Material and Methods

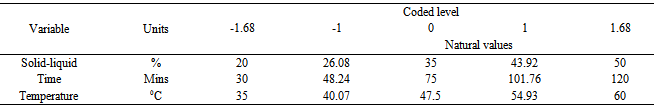

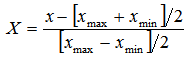

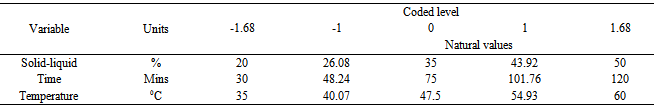

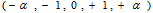

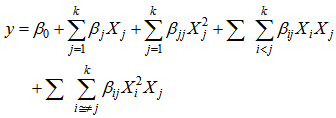

Plant materialsRoselle calyces were purchased from local farmers in Dodoma region, central Tanzania. The plant materials were identified and authenticated by a Plant Taxonomist and a voucher specimen number 4992was deposited at the herbarium in the Botany Department at the University of Dar es Salaam in Tanzania. Calyces were sun dried and inspected to ensure free from extraneous matter.Solvent and reagentsAll chemical reagents used in this experiment were of analytical grade. Deionized water was used for preparation of all solutions. Aqueous solvent was used for extraction of L-ascorbic acid and ferrous (iron II). Experimental designThe study applied both single and multiple factor experimental design. RSM with five-level three-factor central composite rotatable design (CCRD) was employed to determine optimal combination of extraction conditions. Major factors considered were solid-liquid ratio, soaking time and extraction temperature. These factors were used as independent variables to determine the best conditions for optimal extraction of L-ascorbic acid and iron II.Single-factor experiments (SFE) In SFEs each independent variable was assessed to give experimental range. This prevented running experiments in extreme points of the independent variables in multiple factor design. Initially, L-ascorbic acid concentration was estimated in the extracts of SFE. The average value of L-ascorbic acid obtained was used to determine the appropriate range. Based on the results of the SFE, the minimum, average and maximum values for RSM optimization was determined.SFE1: Solid-liquid ratio %( w/v)The solid-liquid ratio was varied from low to very high ratio. Extraction was done at room temperature (26°C) with a fixed time of 90 minutes. The ratio was varied as 1:1 (100%), 1:2 (50%), 1:3 (33%), 1:4 (25%), 1:5 (20%), 1:10 (10%) and 1:20 (5%). These experiments were done in triplicates and the best concentration selected was based on high yield of L-ascorbic acid (mg/100g). SFE2: Extraction time The effect of time on the extraction of the L-ascorbic acid was determined by conducting triplicates SFE with various time periods, when the temperature was fixed at room temperature (26°C) and using the best solid-liquid ratio obtained from SFE1. The time was varied from 10, 15, 30, 45, 60, 90, 120, 180, 240 and 300 minutes. The best extraction time was determined based on the highest yield of L-ascorbic acid (mg/100g) obtained. SFE3 – Temperature To determine the range for temperature, the best concentration and time obtained from SFE1 and SFE2 respectively were used. Then the temperature employed at the intervals of 26°C, 35°C, 45°C, 60°C, 75°C and 100°C. Experiments were done in triplicates and the average L- ascorbic acid (mg/100g) obtained was used to determine the best temperature. Multiple Factor ExperimentsThree-factor central composite rotatable design (CCRD) with five levels was used for this study. The design has a total of 20 experiments. The experiments are grouped in three blocks with the first block include 8 factorial points, the second block utilizes the six axial points of the design and last block runs the six replicates at the center. The distance from the center (α) determines the extreme points, i.e. lowest and highest values of the factors. With CCDR the distance is 1.68. The original variables (xi) were coded using the equation:  | (1) |

and

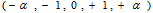

and  are the minimum and maximum values of the original variables. The vector for coded values is defined as

are the minimum and maximum values of the original variables. The vector for coded values is defined as  . Estimation of L-ascorbic acidL-ascorbic acid was estimated using direct iodometric titration described elsewhere [18]. In brief, 25 ml of the sample solution was pipetted into a 250 ml conical flask then titrated with standardized iodine solution using 1 ml of 1 % freshly prepared starch solution as an indicator. The end-point identified by appearance of permanent dark blue-black color which persists for 60 seconds. For each titration three readings were obtained, the average of which gave the experimental titre value. Estimation of ferrous (iron II)Amount of ferrous was determined by atomic absorption spectrophotometry (AAS) official method as reported in an Association of Official Analytical Chemists [19]. In brief, the sample was digested with nitric acid and hydrogen peroxide in a Kjeldatherm (Gerhardt). The digested sample was then analyzed by Inductively Coupled Plasma Atomic Emission Spectrophotometer (ICP-AES) (made in England).AnalysisIn single factor experiments, data were analyzed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 16.0. To assess intra-experiment variation the mean (

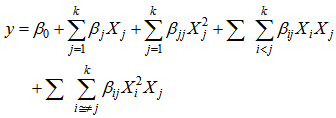

. Estimation of L-ascorbic acidL-ascorbic acid was estimated using direct iodometric titration described elsewhere [18]. In brief, 25 ml of the sample solution was pipetted into a 250 ml conical flask then titrated with standardized iodine solution using 1 ml of 1 % freshly prepared starch solution as an indicator. The end-point identified by appearance of permanent dark blue-black color which persists for 60 seconds. For each titration three readings were obtained, the average of which gave the experimental titre value. Estimation of ferrous (iron II)Amount of ferrous was determined by atomic absorption spectrophotometry (AAS) official method as reported in an Association of Official Analytical Chemists [19]. In brief, the sample was digested with nitric acid and hydrogen peroxide in a Kjeldatherm (Gerhardt). The digested sample was then analyzed by Inductively Coupled Plasma Atomic Emission Spectrophotometer (ICP-AES) (made in England).AnalysisIn single factor experiments, data were analyzed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 16.0. To assess intra-experiment variation the mean ( ) and standard deviation (σ) of triplicates was calculated. The findings were then summarized into bar and line graphs. One way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey’s and Tamhane T2 multiple comparison tests were performed to find significance differences between means (P<0.05). Further analysis of experimental data was done using Design-Expert software version 8.0.7.1. Then data were fitted in a higher order polynomial model given as

) and standard deviation (σ) of triplicates was calculated. The findings were then summarized into bar and line graphs. One way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey’s and Tamhane T2 multiple comparison tests were performed to find significance differences between means (P<0.05). Further analysis of experimental data was done using Design-Expert software version 8.0.7.1. Then data were fitted in a higher order polynomial model given as | (2) |

y represents the response variable (L-ascorbic acid or iron II) and Xi and Xj (i≠j) are independent factors. The  and

and  are regression coefficients for the model intercept, linear, quadratic and interaction terms. The regression parameters obtained from the multiple regression models quantify the impact of the three independent factors on the extraction process taking into account the interaction effect among factors. The interaction terms aim at assessing the association between factors needed to extract the response variables.Model performance was assessed using analysis of variance (ANOVA) and coefficient of determination (R2). Statistical significance was tested at the 95% confidence level. Graphical presentations were used to present the pattern of the relationship between the outcome and the three independent factors.

are regression coefficients for the model intercept, linear, quadratic and interaction terms. The regression parameters obtained from the multiple regression models quantify the impact of the three independent factors on the extraction process taking into account the interaction effect among factors. The interaction terms aim at assessing the association between factors needed to extract the response variables.Model performance was assessed using analysis of variance (ANOVA) and coefficient of determination (R2). Statistical significance was tested at the 95% confidence level. Graphical presentations were used to present the pattern of the relationship between the outcome and the three independent factors.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Single Factor Experiments

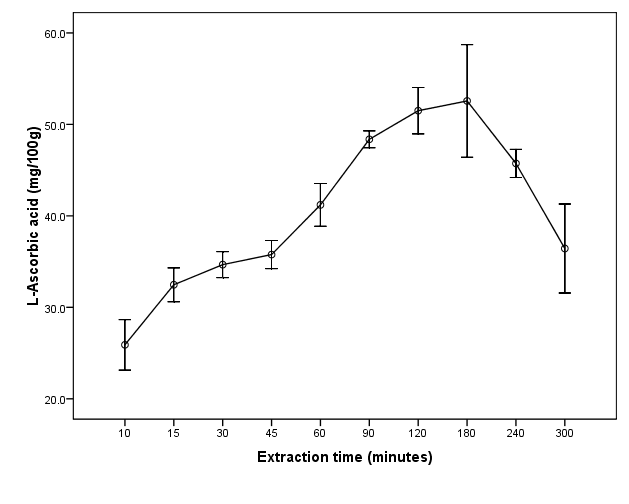

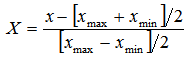

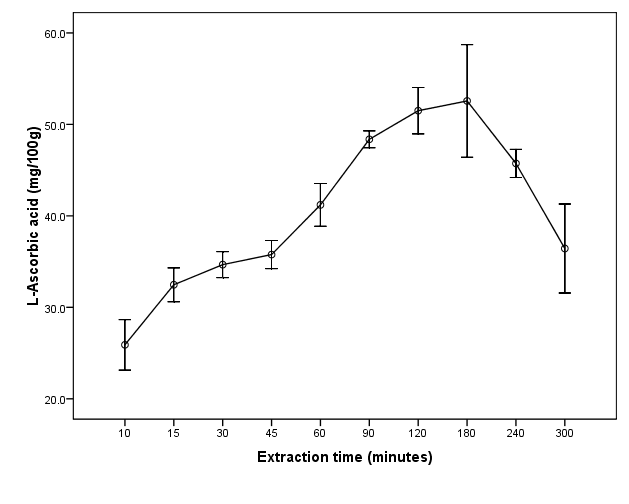

The effects of soaking time on extraction of L-ascorbic acid from Hibiscus sadariffa dried calyces are shown in Figure 1. The yield of L-ascorbic acid increased with the increase in soaking time up to 180 minutes, where the maximum yield was 52.6 ± 5.3 mg/100g. The increase was then followed by a gradual decrease until reaching a minimum yield of 36.4 ± 4.2 mg/100g. There was a sharp increase in L-ascorbic acid from 45 minutes to 90 minutes. After 90 minutes, the slight increase was not statistically significant (P>0.05). Extended soaking time could allow leaching of more L- ascorbic acid and other constituents into a solvent media. Since, L- ascorbic acid is less stable in aqueous solution, it undergoes degradation over time to form dehydro-ascorbic acid (DHAA) and later other products such as diketogulonic acid (DKG) [20,21]. This could explain the observed reduction in yield of L-ascorbic acid beyond 180 minutes. It was also reported that, L-ascorbic acid remain stable in aqueous solution for less than 2 hours [21,22]. Therefore for practical reasons, 30, 75 and 120 minutes was selected as minimum, middle and maximum time respectively for RSM.  | Figure 1. Effect of extraction time on extraction of L-ascorbic acid from dried calyces of Hibiscus sabdariffa L |

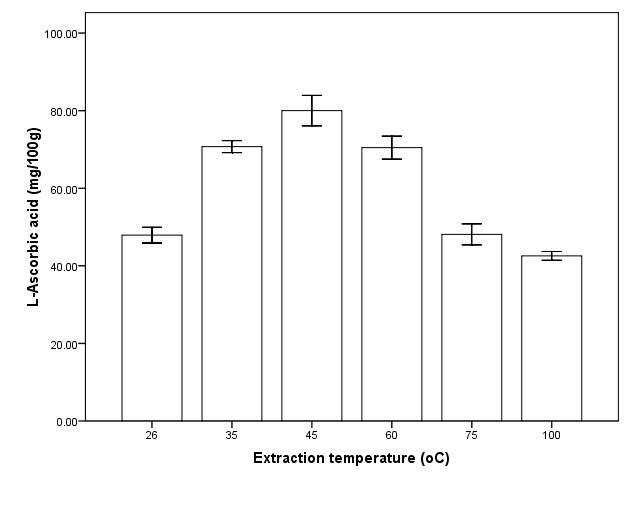

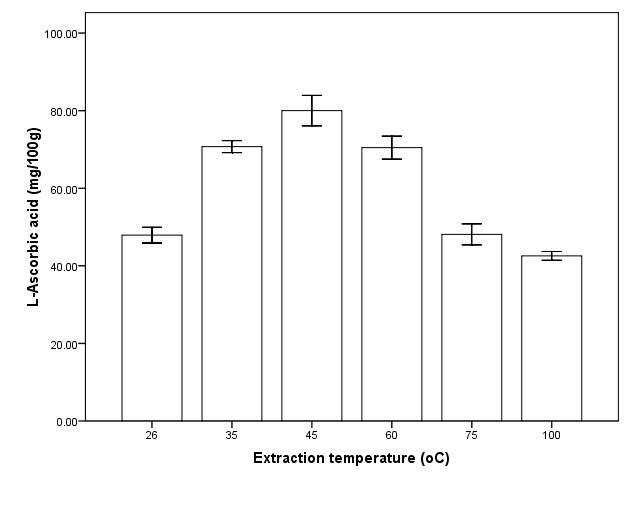

Extraction temperature was investigated that is among of the important extraction parameters. Extraction of L-ascorbic acid increase with increase in temperature and reached a peak (80 ± 3.4 mg/100g) at 45oC. There was a drastic decrease in L-ascorbic acid between 60 and 75℃ (P<0.05) followed by slight decrease thereafter (Figure 2). Generally, elevated temperatures result in improved extraction efficiencies. This could explain the observed increase in L-ascorbic acid with temperature. However, L-ascorbic acid in solution degrade at high temperature [19,22–25]. The observed decrease in amount of L-ascorbic acid after 60℃ may indicate degradation. For the purpose of RSM the temperature range of 35℃, 48℃ and 60℃ was chosen as low, middle and higher temperature respectively.  | Figure 2. Effect of extraction temperature on extraction of L-ascorbic acid from dried calyces of Hibiscus sabdariffa L |

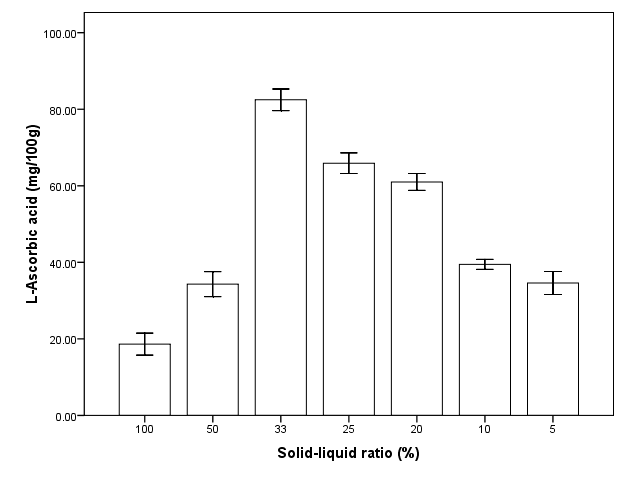

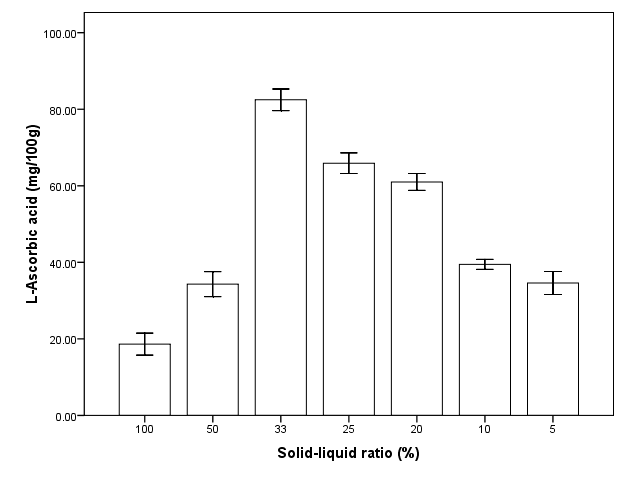

Solid-liquid ratio was also an essential extraction parameter that was assessed in single factor experiment. The maximum amount of L-ascorbic acid (82.5 ± 2.4 mg/100g) obtained at 33 % (Figure 3). The yield was then gradually decreased with an increase in extraction solvent. The drop in yield indicates that over dilution is not ideal in extracting this molecule. Based on these findings, minimum, middle and maximum solid-liquid ratio was chosen at 20%, 35% and 50% respectively for RSM. | Figure 3. Effect of solid liquid ratio on extraction of L-ascorbic acid from dried calyces of Hibiscus sabdariffa L |

3.2. Multiple Factor Experiment

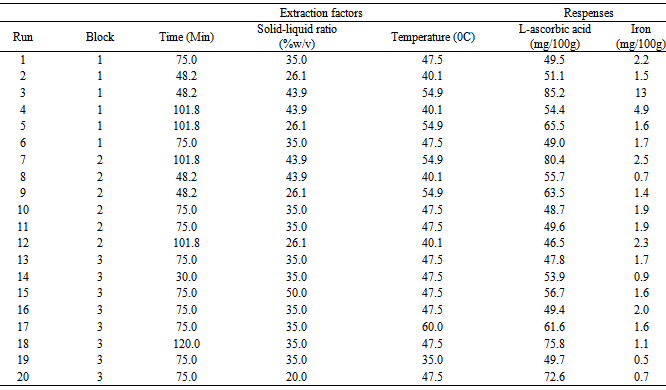

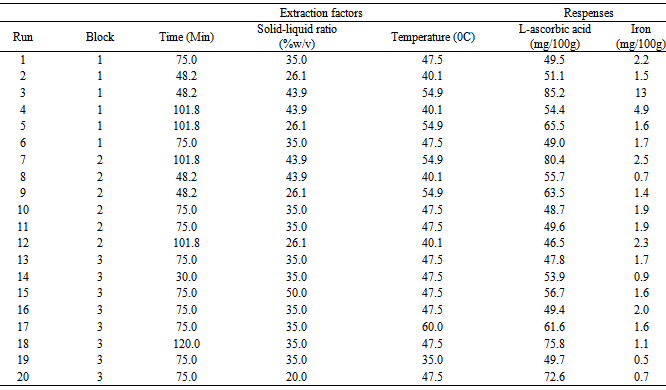

The combinations for the three factors (Table 1) were established. Two experimental replicas were conducted for each combination of the factors.Table 1. Coded and original values for independent variables used in the CCRD for optimization

|

| |

|

The amount of L-ascorbic acid obtained in multiple factor experiments were higher (85.2 mg/100g) than those obtained from single factor experiments (82.5 mg/100g). This could be due to interaction effect of three independent factors. In contrast with our findings, a study in Nigeria reported ascorbic acid content of red calyces as 63.5 mg/100g [7]. The disagreement could be due to the influence of geographical distribution of roselle. Values for iron II had large range which might indicate presence of extreme values (outliers). This response was transformed during analysis.

3.3. Analysis of Variance

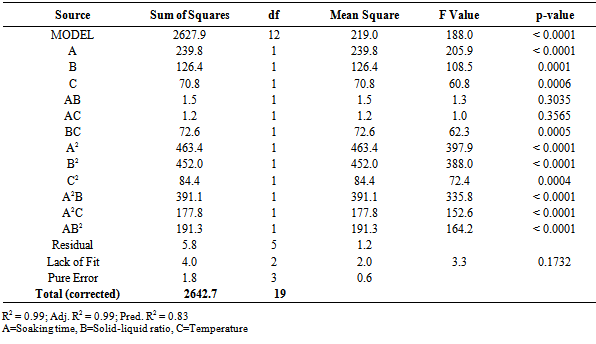

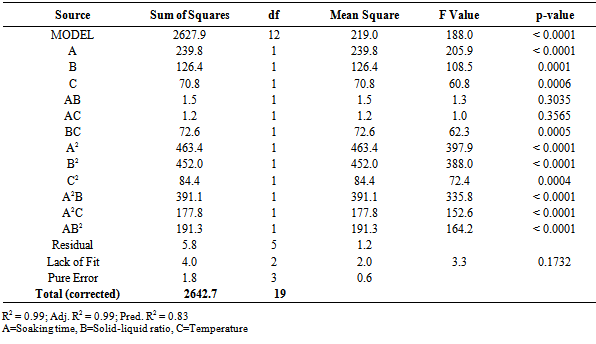

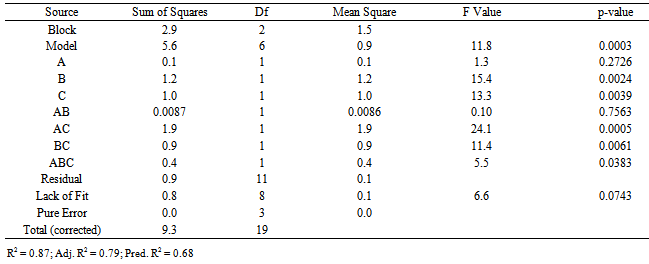

L-ascorbic Acid: The reduced cubic model was fitted for the L-ascorbic acid data to obtain optimization of the factors. Results of the ANOVA are presented in Table 3.The model was significant (p-value <0.001) and had a good fit (Lack of Fit p-value =0.1732). Significant terms include A, B, C, BC, A2, B2, C2, A2B, A2C and AB2. The terms AB and AC, although not significant, could not be removed from the model as they support the hierarchy of the model function. High R2 value indicates factors explain well the response (Table 3).Table 2. Experimental Design and obtained results

|

| |

|

Table 3. ANOVA for L-ascorbic acid obtained from reduced cubic model

|

| |

|

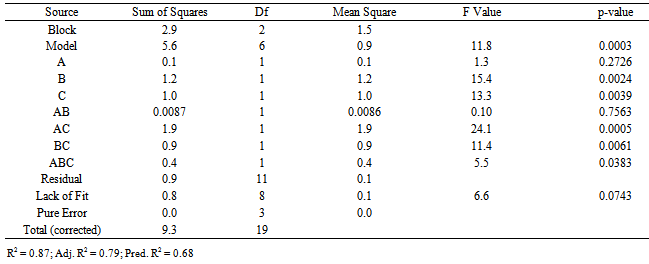

Iron II: The reduced cubic model was fitted for the ferrous iron data to obtain optimization of the factors (Table 4). Table 4. ANOVA for ferrous iron obtained from reduced cubic model

|

| |

|

The model was significant (p-value <0.001) and had a good fit (Lack of Fit p-value =0.074). Significant terms for extracting iron II include B, C, AC, BC and ABC. The terms A and AB, although not significant, could not be removed from the model as they support the hierarchy of the model function. The value of R2 value indicates factors explain the response sufficiently. Functions for the models with actual factor values are as follows:L-ascorbic acid ASCORBIC ACID =-40.69 +13.39 * TIME -16.65 * CONC.+2.32 * TEMP.-7.16E-003 * TIME * CONC. -0.20 * TIME * TEMP. +0.045 * CONC. * TEMP. -0.12 * TIME2. +0.34 * CONC.2 +0.044 * TEMP.2 +1.70E-003 * TIME2 * CONC. +1.37E-003 * TIME2 * TEMP. -3.56E-003 * TIME * CONC.2Ferrous Ln(IRON) =50.20 -0.25 * TIME - 1.01 * CONC. - 0.55 * TEMP.+0.011 * TIME * CONC. +5.52E-003 * TIME * TEMP. +0.022 * CONC. * TEMP. -2.28E-004 * TIME * CONC. * TEMP.

3.4. Graphical Presentation

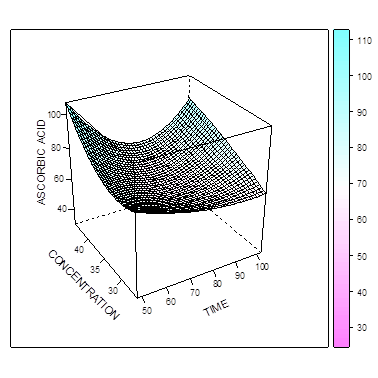

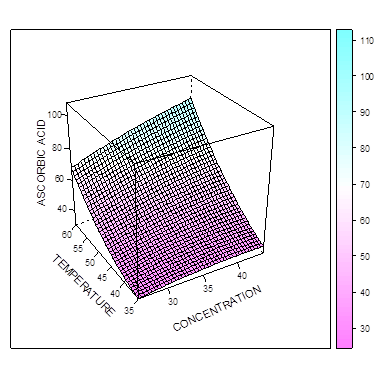

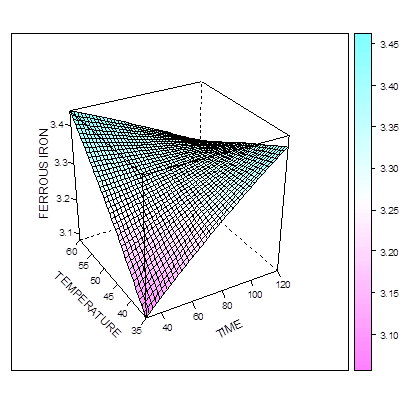

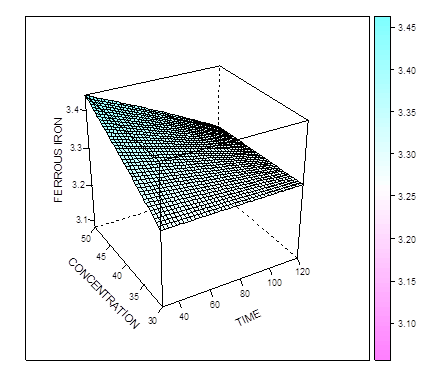

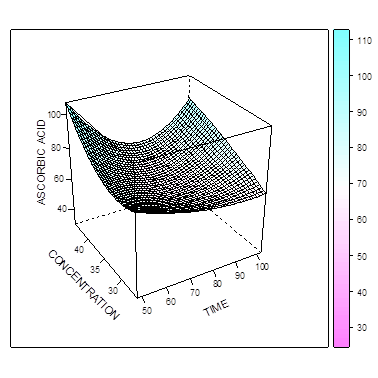

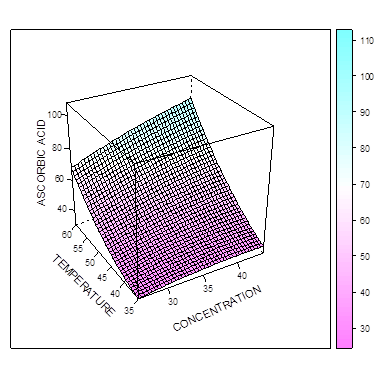

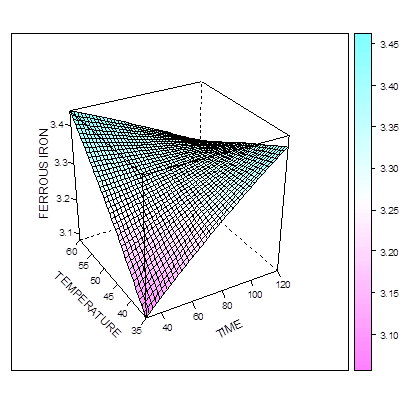

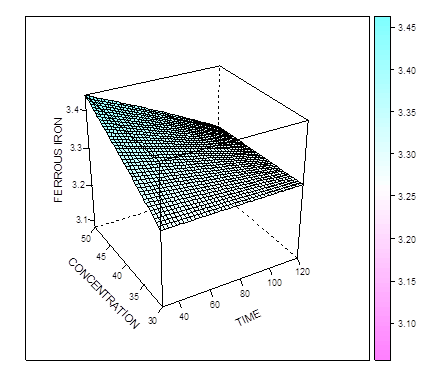

The Figure 4 and 5 show that the amount of L-ascorbic acid extracted increases as the temperature and concentration increases. In figure 5, maximum L-ascorbic acid can be obtained at concentration of 43.7% and time of 50 minutes. The figure 6 shows that maximum iron II could be extracted at the concentration of about 42% and time of about 95 mins. When temperature and time were combined (Figure 7), the optimal extraction of Iron II was obtained at 48 mins and 55 degrees. Increasing these factors (esp. time) reduced the amount of iron II extracted.  | Figure 4. Effect of time and concentration on extraction of L-ascorbic acid at constant temperature |

| Figure 5. Effect of tempreature and concentration on extraction of L-ascorbic acid at constant time |

| Figure 6. Effect of time and temperature on extraction of ferrous at constant concentration |

| Figure 7. Effect of time and concentration on extraction ferrous at constant temperature |

3.5. Numerical Optimization

The optimized extraction parameters for Hibiscus sabdariffa L calyces were time 48 minutes, concentration 44% and temperature 55°C. Under these optimized extraction conditions L-ascorbic acid and iron II were 83.1 and 7.8 mg/100g respectively.

4. Conclusions

The study demonstrate the presence of both iron and ascorbic acid in the dried roselle calyces grown in Tanzania. In addition, RSM helped to study interaction effect of extraction temperature, soaking time and solid-solvent ratio. Industries may adopt these optimal extraction conditions for production of roselle beverages to maximize health benefits of roselle.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors express their gratitude to Grand Challenges Canada-stars in Global health round 4 for financially supporting this project (Grant number 0272-01). We are grateful to Mr. Haji O. Sulemani, a Plant Taxonomist at the Department of Botany, University of Dar es Salaam in Tanzania for taxonomical identification and authentication of the plant materials studied in this project. We are also grateful to all staffs of Department of Traditional Medicine Research at the National institute for Medical research, Tanzania for their invaluable technical support during laboratory investigation.

References

| [1] | Plotto A. Post-Production Management for Improved Market Access. 1st ed. François Mazaud, Alexandra Röttger KS, editor. FAO; 2004 p. 1–19. |

| [2] | Hudson T. A Research review on the use of Hibiscus sabdariffa L. Better Medicine. National Network of Holistic Practitioner Communities. Oct. 26 2011.http://bettermedicine.net/article/research-review-use-hibiscus-sabdariffa-tori-hudson-nd |

| [3] | Ramirez-Rodrigues MM, Plaza ML, Azeredo A, Balaban MO, Marshall MR. Physicochemical and phytochemical properties of cold and hot water extraction from Hibiscus sabdariffa. J. Food Sci. 2011;76(3):C428–35. |

| [4] | Ali BH, Al Wabel N, Blunden G. Phytochemical, pharmacological and toxicological aspects of Hibiscus sabdariffa L.: a review. Phytother. Res. 2005;19(5):369–75. |

| [5] | Ijeomah AU, Ugwuona FU, Abdullahi H. Phytochemical composition and antioxidant properties of Hibiscus sabdariffa and Moringa oleifera. Nigerian Journal of Agriculture, Food and Environment. 2012;8(1):10–6. |

| [6] | Wong PK, Yusof S, Ghazali HM, Che Man YB Physico-chemical characteristics of Roselle (Hibiscus sabdariffa L.) calyx and effect of processing and storage on the stability of anthocyanins in roselle juice. .Nutr Food Sci. 2002;32:68-78 |

| [7] | S.O Babalola, A.O Babalola O. A. Compositional attributes of the calyces of roselle (Hibiscus sabdariffa L.). J. food Technol. Africa. 2001;6(4):133–4. |

| [8] | Falade OS, Otemuyiwa IO, Oladipo A, Oyedapo OO, Akinpelu BA, Adewusi SRA. The chemical composition and membrane stability activity of some herbs used in local therapy for anemia. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2005;102(1):15–22. |

| [9] | Nnam NM, Onyeke NG. Chemical composition of two varieties of sorrel (Hibiscus sabdariffa L.), calyces and the drinks made from them. Plant Foods Hum. Nutr. 2003;58(3):1–7. |

| [10] | Odigie IP, Ettarh RR, Adigun SA. Chronic administration of aqueous extract of Hibiscus sabdariffa attenuates hypertension and reverses cardiac hypertrophy in 2K-1C hypertensive rats. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2003 ;86(2-3):181–5. |

| [11] | Herrera-Arellano a, Flores-Romero S, Chávez-Soto M a, Tortoriello J. Effectiveness and tolerability of a standardized extract from Hibiscus sabdariffa in patients with mild to moderate hypertension: a controlled and randomized clinical trial. Phytomedicine. 2004;11(5):375–82. |

| [12] | Haji Faraji M, Haji Tarkhani A. The effect of sour tea (Hibiscus sabdariffa) on essential hypertension. J. Ethnopharmacol. 1999;65(3):231–6. |

| [13] | Mckay DL, Chen CO, Saltzman E, Blumberg JB. Hibiscus Sabdariffa L. Tea (Tisane) Lowers Blood Pressure in Prehypertensive and Mildly Hypertensive Adults 1 – 4. The Journal of Nutrition. 2010;1–6. |

| [14] | Lin T-L, Lin H-H, Chen C-C, Lin M-C, Chou M-C, Wang C-J. Hibiscus sabdariffa extract reduces serum cholesterol in men and women. Nutr. Res. 2007;27(3):140–5. |

| [15] | Bolade MK, Oluwalana IB, Ojo O. Commercial Practice of Roselle ( Hibiscus sabdariffa L .) Beverage Production : Optimization of Hot Water Extraction and Sweetness Level. World J. Agric. Sci. 2009;5(1):126–31. |

| [16] | Pinelo M, Rubilar M, Jerez M, Sineiro J, Núñez MJ. Effect of solvent, temperature, and solvent-to-solid ratio on the total phenolic content and antiradical activity of extracts from different components of grape pomace. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2005;53(6):2111–7. |

| [17] | D.B. Uma, C.W.Ho WMW. Optimization of Extraction Parameters of Total Phenolic Compounds from Henna (Lawsonia inermis) Leaves. Sains Malaysiana. 2010; 39(1): 119–28. |

| [18] | Suntornsuk L, Gritsanapun W, Nilkamhank S, Paochom A. Quantitation of vitamin C content in herbal juice using direct titration. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2002;28(5):849–55. |

| [19] | AOAC 5th edition 2006. |

| [20] | Yuan JP, Chen F. Degradation of Ascorbic Acid in Aqueous Solution. J. Agric. Food Chem.1998;46(12):5078–82. |

| [21] | Odriozola-Serrano I, Hernández-Jover T, Martín-Belloso O. Comparative evaluation of UV-HPLC methods and reducing agents to determine vitamin C in fruits. Food Chem. 2007;105(3):1151–8. |

| [22] | Spínola V, Mendes B, Câmara JS, Castilho PC. Effect of time and temperature on vitamin C stability in horticultural extracts. UHPLC-PDA vs iodometric titration as analytical methods. LWT - Food Sci. Technol. 2013;50(2):489–95. |

| [23] | Iwase H. Use of an amino acid in the mobile phase for the determination of ascorbic acid in food by high-performance liquid chromatography with electrochemical detection. J. Chromatogr. A. 2000;881(1-2):317–26. |

| [24] | Hernández Y, Lobo MG, González M. Determination of vitamin C in tropical fruits: A comparative evaluation of methods. Food Chem. 2006;96(4):654–64. |

| [25] | Paul R, Ghosh U. Effect of thermal treatment on ascorbic acid content of pomegranate juice. Indian I Biotechnol 2012; 11:309–13. |

and

and  are the minimum and maximum values of the original variables. The vector for coded values is defined as

are the minimum and maximum values of the original variables. The vector for coded values is defined as  . Estimation of L-ascorbic acidL-ascorbic acid was estimated using direct iodometric titration described elsewhere [18]. In brief, 25 ml of the sample solution was pipetted into a 250 ml conical flask then titrated with standardized iodine solution using 1 ml of 1 % freshly prepared starch solution as an indicator. The end-point identified by appearance of permanent dark blue-black color which persists for 60 seconds. For each titration three readings were obtained, the average of which gave the experimental titre value. Estimation of ferrous (iron II)Amount of ferrous was determined by atomic absorption spectrophotometry (AAS) official method as reported in an Association of Official Analytical Chemists [19]. In brief, the sample was digested with nitric acid and hydrogen peroxide in a Kjeldatherm (Gerhardt). The digested sample was then analyzed by Inductively Coupled Plasma Atomic Emission Spectrophotometer (ICP-AES) (made in England).AnalysisIn single factor experiments, data were analyzed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 16.0. To assess intra-experiment variation the mean (

. Estimation of L-ascorbic acidL-ascorbic acid was estimated using direct iodometric titration described elsewhere [18]. In brief, 25 ml of the sample solution was pipetted into a 250 ml conical flask then titrated with standardized iodine solution using 1 ml of 1 % freshly prepared starch solution as an indicator. The end-point identified by appearance of permanent dark blue-black color which persists for 60 seconds. For each titration three readings were obtained, the average of which gave the experimental titre value. Estimation of ferrous (iron II)Amount of ferrous was determined by atomic absorption spectrophotometry (AAS) official method as reported in an Association of Official Analytical Chemists [19]. In brief, the sample was digested with nitric acid and hydrogen peroxide in a Kjeldatherm (Gerhardt). The digested sample was then analyzed by Inductively Coupled Plasma Atomic Emission Spectrophotometer (ICP-AES) (made in England).AnalysisIn single factor experiments, data were analyzed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 16.0. To assess intra-experiment variation the mean ( ) and standard deviation (σ) of triplicates was calculated. The findings were then summarized into bar and line graphs. One way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey’s and Tamhane T2 multiple comparison tests were performed to find significance differences between means (P<0.05). Further analysis of experimental data was done using Design-Expert software version 8.0.7.1. Then data were fitted in a higher order polynomial model given as

) and standard deviation (σ) of triplicates was calculated. The findings were then summarized into bar and line graphs. One way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey’s and Tamhane T2 multiple comparison tests were performed to find significance differences between means (P<0.05). Further analysis of experimental data was done using Design-Expert software version 8.0.7.1. Then data were fitted in a higher order polynomial model given as

and

and  are regression coefficients for the model intercept, linear, quadratic and interaction terms. The regression parameters obtained from the multiple regression models quantify the impact of the three independent factors on the extraction process taking into account the interaction effect among factors. The interaction terms aim at assessing the association between factors needed to extract the response variables.Model performance was assessed using analysis of variance (ANOVA) and coefficient of determination (R2). Statistical significance was tested at the 95% confidence level. Graphical presentations were used to present the pattern of the relationship between the outcome and the three independent factors.

are regression coefficients for the model intercept, linear, quadratic and interaction terms. The regression parameters obtained from the multiple regression models quantify the impact of the three independent factors on the extraction process taking into account the interaction effect among factors. The interaction terms aim at assessing the association between factors needed to extract the response variables.Model performance was assessed using analysis of variance (ANOVA) and coefficient of determination (R2). Statistical significance was tested at the 95% confidence level. Graphical presentations were used to present the pattern of the relationship between the outcome and the three independent factors.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML