-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Food Science and Nutrition Engineering

p-ISSN: 2166-5168 e-ISSN: 2166-5192

2011; 1(1): 5-7

doi: 10.5923/j.food.20110101.02

Microbiology of Some Selected Nigerian Oils Stored under Different Conditions

Adelodun L. Kolapo , Gabriel R. Oladimeji

Biology Department, the Polytechnic, Ibadan. Ibadan.Nigeria

Correspondence to: Adelodun L. Kolapo , Biology Department, the Polytechnic, Ibadan. Ibadan.Nigeria.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

The effect of storage conditions on the microbiological qualities of oils extracted from selected oilseeds was investigated. Oils were stored at room temperature, display condition and refrigeration temperature. The highest bacterial count was observed in Groundnut oil and soybean oil and the least in cashewnut oil with the oil stored under display condition having the highest count. On the contrary, cashewnut oil had the highest fungal count and soybean oil the least. The microbial profile of the associated organisms consists of Bacillus subtilis B. licheniformis, Proteus vulgaris, P. mirabilis, Aspergillus niger and Rhizopus spp. The slightly elevated microbial count of oils stored under display conditions in the present work seems to be suggesting that the use of antioxidants with antimicrobial property may be helpful in slowing down microbial growth and deteroration in the oils exposed to similar conditions in most Nigerian markets.

Keywords: Storage, Microorganisms, Oils, Market

Cite this paper: Adelodun L. Kolapo , Gabriel R. Oladimeji , "Microbiology of Some Selected Nigerian Oils Stored under Different Conditions", International Journal of Food Science and Nutrition Engineering, Vol. 1 No. 1, 2011, pp. 5-7. doi: 10.5923/j.food.20110101.02.

1. Introduction

- Oils crops and their products are regarded as vital parts of the world’s food supply[1].Oilseeds have been shown to be good sources of lipids and proteins and their defatted cakes could be used as protein supplement in human nutrition[2].Fokou et al[3]reported that, in addition to good nutritional value of some Cucurbitaceae oilseeds, they are effective soup thickners and when cooked and dried, can serve as snacks. Extracted oils from oilseeds have found diverse applications such as in cooking, food manufacture, soap manufacture, tin plating, paints, cosmetics, printing inks, leather making and pharmaceutical uses[3].Report on the nutritive, physico-chemical properties and mineral compositions of the oils extracted from many oilseeds have been documented[4-8]. Oils may go rancid and develop an unpleasant odour and flavour if incorrectly stored. The main factors that cause rancidity (in addition to moisture, bacteria and enzymes) are light, heat, air and some types of metals[9].The storage properties: especially the physico-chemical and microbiology of some edible oils stored at room temperature have been investigated[1,7].At marketing stage, the condition that oils are subjected to are quite different from room temperature condition, as most oil marketers in Nigeria display their merchandise outside, under the sun on a daily basis. The aim of the present work is to investigate the effect of this display condition on the mic-robiological qualities of some selected edible oils in Nigeria.

2. Materials and Methods

- Samples of five oilseeds namely, Groundnut, soybean, Melon, Cashew and Coconut were purchased from local market in Ibadan and Ogbomosho, Nigeria. The samples were dehulled, sundried for 48-72 h, ground in a Kenwood blender to reduce their particles size so as to improve yield. The oils were obtained by cold solvent extraction of the ground samples using n-hexane. Two hundred millilitres of n-hexane was mixed with 500gm of each samle in five batches. The mixture was shaken vigorously and left for about 72 h to settle. The supernatant was slowly decanted and poured into a sterile reagent bottle. The extract from all the five batches were pooled together and allowed to settle again for 24 h. The mixture was distilled by simple distillation. The recovered oil was transferred into sterile bottle, while recycled n-hexane was kept for further extraction. The extracted oil was later dried over anhydrous sodium sulphate in the oven at 105C. The oil sample thus obtained was divided into three parts. A portion was kept inside a cupboard (room temperature), the second was kept in a refrigerator while the remaining portion was kept daily under the sun thus simulating the display condition.The storage condition experiment was done in March 2006. The five oil samples were stored for four weeks. The method of Omafuvbe et al[11]was adapted for the enumeration of microbial population in the stored oil samples. Counts were taken at one week interval. Counted bacteria colonies were expressed as colony forming unit per ml(cfu/ml) of samples. Mean values of triplicate plates were recorded. For the fungal counts, potato dextrose agar (PDA)and incubation temprature of 28C for 2-3 days were used. Pure cultures of the isolated bacteria and fungi were obtained by repeated streaking. Bacterial isolates were characterized and identified according to Cowan and Steel[12]and definition given with reference to Bergey’s manual[13].Fungal isolates were identified using the key given by Onions et al[14].The statistical analysis of the data was by Analysis of Variance(ANOVA) using 5% level of significance. A Two-way ANOVA analysis was used to test for significance of difference between the storage conditions and between the oil types.

3. Results and Discussion

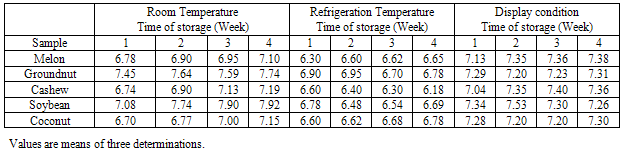

- The results of total bacterial count of five samples of oil stored under the three conditions are shown in Table 1. The highest count was observed in both Groundnut and soybean oil, while cashew oil had the least bacterial count. With regard to the storage conditions, oils stored under display conditions had the highest count while those stored at refrigeration temperature had the least bacterial count. However, a Two-way ANOVA test between storage treatments depicted no significant difference (P>0.05) between the oil types and the storage conditions. The slightly increase in bacterial count with the length of storage (especially at room and display conditions) is in agreement with the earlier report of Ilori et al[10].This result may be lending credence to the assertion of Yano et al[15]who submitted that herbs and spices have been used for taste enhancement and as preservatives in various foods and cusines because of their ability to inhibit microbial growth that often contribute to lipid peroxidation in oil rich foods.The fungal count of the stored oil samples is shown in Table 2. Highest fungal count was observed in cashew oil and the least in soybean oil, an observation that seems to contrast bacterial count. There was no significant difference (P>0.05) for both the kind of oil and storage conditions. The increase in fungal count with the length of storage compares favourably with the report of Ilori et al[10].The distribution of bacterial and fungal isolates from stored oil samples is shown in Table 3. The microflora of the stored oil is similar to that reported for some stored Nigerian foodstuffs [10,16,17].Though earlier report did not established the production of aflatoxin by some species of Aspergillus in stored oil[10], yet the contribution of microbial growth to peroxidation is a well established fact[15,18,19].The slightly elevated microbial count of oils stored under display conditions observed in the present work seems to be suggesting that the use of antioxidants with antimicrobial activity may be helpful in slowing down microbial growth and deterioration in the oils being subjected to similar conditions in most Nigerian markets.

|

|

|

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-Text HTML

Full-Text HTML