-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Energy and Power

p-ISSN: 2163-159X e-ISSN: 2163-1603

2025; 14(1): 12-21

doi:10.5923/j.ep.20251401.02

Received: Nov. 2, 2025; Accepted: Nov. 23, 2025; Published: Nov. 25, 2025

The Impact of Biofuel Blending on the Cost of Petroleum Fuel in Zambia

Lighton Musukwa1, Francis D. Yamba2

1Department of Mechanical Engineering, School of Engineering, The University of Zambia, Lusaka, Zambia

2University of Zambia, Centre for Energy, Environment and Engineering, Zambia, Lusaka, Zambia

Correspondence to: Lighton Musukwa, Department of Mechanical Engineering, School of Engineering, The University of Zambia, Lusaka, Zambia.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

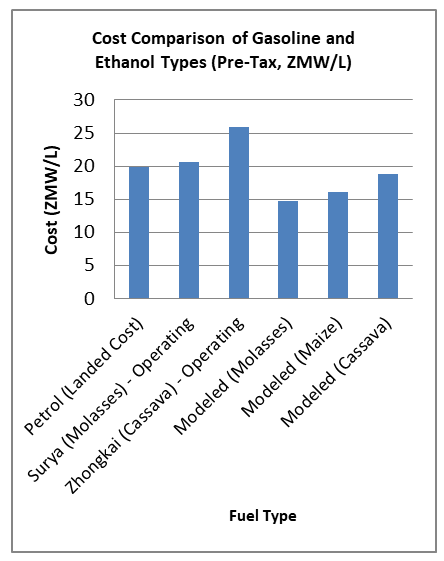

Zambia’s dependence on imported petroleum fuels continues to strain foreign exchange reserves and hinder progress toward energy security and sustainable development. This study investigates the impact of biofuel blending on petroleum fuel costs in Zambia through a techno-economic analysis of a proposed 100,000 L/day ethanol facility using molasses, maize, and cassava. The analysis integrates process design, cost modeling, and fiscal policy factors, including Zambia’s 60% excise duty and 16% VAT, which collectively add approximately 46% to final fuel prices. The research reveals that while optimised models demonstrate strong cost-saving potential with molasses-based ethanol at ZMW 14.72/L (USD 0.64/L), maize at ZMW 16.10/L (USD 0.70/L), and cassava at ZMW 18.86/L (USD 0.82/L), the performance of existing plants tells a different story. Operational facilities such as Surya Biofuels (molasses) and Zhongkai (cassava) report production costs of ZMW 20.70/L and ZMW 25.99/L, respectively, making them 4.4% and 31.0% more expensive than the pre-tax landed cost of petrol (ZMW 19.83/L). This discrepancy highlights a critical gap between potential and reality, shaped by operational inefficiencies, transport bottlenecks, and a prohibitive tax regime. Despite current cost challenges, the study identifies significant economic, environmental, and social co-benefits. A nationwide E10 ethanol-petrol blend could displace 4.5 million litres of petrol per month, saving approximately USD 46.5 million (or ZMW 1,071.036 million at an exchange rate of 23.03 ZMW/USD). Environmentally, ethanol blending reduces greenhouse-gas emissions by 35 – 45%, while cassava out-grower schemes have increased rural household incomes by 79%, benefiting 5,000 farmers in Northern Province. The study concludes that ethanol blending in Zambia is technically feasible and environmentally beneficial, but its economic viability depends on targeted policy interventions, notably reducing excise duty to 40%, exempting ethanol from VAT, and investing in rural infrastructure to reduce feedstock transport costs. Bridging the gap between the high costs of current operations and the promising economics of optimised production requires coordinated fiscal reforms, public–private investment, and continued research into feedstock optimization, enzyme efficiency, and decentralized production systems.

Keywords: Ethanol production, Biofuel blending, Feedstock optimization, Economic viability, Environmental impact, Social development

Cite this paper: Lighton Musukwa, Francis D. Yamba, The Impact of Biofuel Blending on the Cost of Petroleum Fuel in Zambia, Energy and Power, Vol. 14 No. 1, 2025, pp. 12-21. doi: 10.5923/j.ep.20251401.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- The escalating global energy demand, driven by population growth and industrialization, has intensified the reliance on fossil fuels, leading to significant environmental concerns such as greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and climate change [1], [2]. In response, a global shift towards renewable energy sources has gained momentum, with biofuels emerging as a key alternative to conventional petroleum products. Biofuels, derived from biomass such as agricultural crops and organic waste, can be blended with traditional fuels to reduce dependence on non-renewable resources and mitigate environmental impact [3]. Many nations have adopted biofuel policies, such as blending mandates, to advance energy security, support domestic agriculture, and meet climate targets. The European Union's Renewable Energy Directive (RED) and the United States' Renewable Fuel Standard (RFS) are prominent examples of policies that have spurred biofuel market growth [4].In this context, Zambia, a land-linked nation entirely dependent on imported petroleum, faces persistent economic strain from volatile international oil prices and foreign exchange expenditure [5]. The country’s energy portfolio is dominated by firewood, hydropower, solar photovoltaic (PV), and imported petroleum products, with the latter delivered via the Tazama pipeline and road tankers from ports in Tanzania, Mozambique, and South Africa [6]. The rising cost of fuel imports has prompted the Government of the Republic of Zambia (GRZ) to explore biofuel blending as a strategic measure to reduce pump prices, enhance energy security, and stimulate rural development, as outlined in its Eighth National Development Plan (8NDP) [7].Zambia's interest in biofuels is not new. In 2011, the government announced blending targets of 5% for biodiesel (B5) and 10% for ethanol (E10), aligning with similar initiatives in other African nations like Nigeria, Ethiopia, and South Africa [8]. The country possesses abundant arable land and a favorable climate for cultivating dedicated energy crops, with maize, cassava, and molasses identified as primary feedstocks. Commercial entities like Sunbird Bioenergy, utilizing cassava, and Surya Biofuels, which was the first to produce fuel-grade ethanol from molasses, have already established operations [5]. Sunbird Bioenergy, for instance, plans to produce over 100 million liters of renewable fuel for E10, E20, and E85 blends, aiming to reduce fossil fuel imports and GHG emissions.Despite this potential and political will, a significant knowledge gap persists. There is a lack of comprehensive, localized data on the actual cost of biofuel production in Zambia and its true impact on the final cost of petroleum fuel [9]. While the government posits that blending will lower fuel costs, the economic viability is contingent on numerous factors, including feedstock costs, conversion efficiency, and the existing fiscal framework. Most research has focused on the environmental benefits of biofuels, with far less attention paid to a rigorous economic analysis tailored to the Zambian context [10]. This study aims to bridge that gap by conducting a detailed techno-economic analysis (TEA) of ethanol production from molasses, maize, and cassava. The general objective is to investigate the impact of biofuel blending on the cost of petroleum fuel in Zambia, thereby providing empirical evidence to guide policymakers, attract investment, and foster the sustainable development of a domestic biofuel industry.

2. Literature Review

- The promotion of biofuels is driven by a confluence of objectives, including climate change mitigation, energy security, and rural economic development [11]. Biofuels, principally ethanol and biodiesel, are derived from biomass and can be blended with conventional fuels. Ethanol is commonly produced from sugar- or starch-based crops like sugarcane, corn, and cassava, while biodiesel is derived from vegetable oils and animal fats [12]. The blending of ethanol with gasoline, typically in ratios of 10% (E10) or higher, is a widespread practice globally, with countries like Brazil, the United States, and China implementing national mandates to drive adoption [4], [13]. These policies create stable markets for biofuels, which are often more expensive to produce than their fossil fuel counterparts and thus depend on policy support for their consumption.

2.1. Cost of Biofuel Production and Economic Viability

- The economic viability of biofuel production is a critical determinant of its success. The Levelized Cost of Energy (LCOE) is a standard metric used to compare the cost-competitiveness of different energy technologies, accounting for capital costs, operating expenses, feedstock costs, and financing over a plant's lifetime [14]. Feedstock cost is the single largest component, often comprising 40% to 70% of the total production cost for first-generation biofuels [15]. For example, studies have shown that the production cost of ethanol from sugarcane in Brazil is lower than that of corn-based ethanol in the United States, primarily due to lower feedstock costs [16].The impact of blending on pump prices depends directly on the relative cost of ethanol and gasoline. If ethanol production costs are lower than the landed cost of petroleum, blending can lead to consumer savings [17]. However, this is often complicated by fiscal policies. In Zambia, a prohibitive 60% excise duty and 16% VAT are levied on ethanol, which can negate any production cost advantage and make the final blended fuel more expensive [5]. This contrasts with countries like Zimbabwe, where a preferential tax rate on blended fuels is used to ensure consumer affordability and drive market adoption.

2.2. Environmental and Socio-Economic Impacts

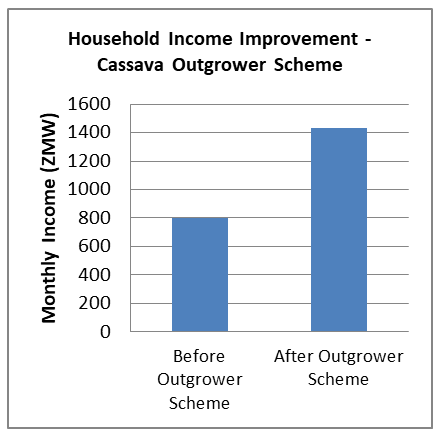

- The environmental sustainability of biofuels is a complex and widely debated topic. Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) is the standard methodology for evaluating the overall environmental footprint, from feedstock cultivation to end-use combustion [18]. While biofuels are often promoted as a low-carbon alternative, their actual GHG emission savings vary significantly based on feedstock type, production process, and land-use change (LUC) [19]. Second-generation biofuels from non-food sources like agricultural residues (lignocellulosic biomass) generally offer higher GHG reductions, potentially up to 86%, compared to first-generation biofuels from food crops [10], [20]. The study by Musukwa [5] found that in Zambia, molasses-based ethanol could reduce GHG emissions by up to 45%, maize by 40%, and cassava by 35% compared to gasoline.Beyond GHG emissions, biofuel production impacts water resources, biodiversity, and soil quality. The expansion of energy crops can lead to habitat loss and increased water consumption, particularly in water-stressed regions [21], [22]. The "food versus fuel" debate is another critical socio-economic consideration, as the use of food crops like maize for fuel can impact food prices and availability [23]. However, biofuel production can also be a powerful engine for rural development. In Zambia, cassava out-grower schemes have been shown to increase rural household incomes by 79%, creating jobs and stimulating local economies [5]. This aligns with findings from other developing nations where biofuel initiatives are seen as a tool to uplift vulnerable communities and reduce poverty.

2.3. Research Gap in the Zambian Context

- The environmental sustainability of biofuels is a complex and widely debated topic. Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) is the standard methodology for evaluating the overall environmental footprint, from feedstock cultivation to end-use combustion [18]. While biofuels are often promoted as a low-carbon alternative, their actual GHG emission savings vary significantly based on feedstock type, production process, and land-use change (LUC) [19]. Second-generation biofuels from non-food sources like agricultural residues (lignocellulosic biomass) generally offer higher GHG reductions, potentially up to 86%, compared to first-generation biofuels from food crops [10], [20]. The study by Musukwa [5] found that in Zambia, molasses-based ethanol could reduce GHG emissions by up to 45%, maize by 40%, and cassava by 35% compared to gasoline.Beyond GHG emissions, biofuel production impacts water resources, biodiversity, and soil quality. The expansion of energy crops can lead to habitat loss and increased water consumption, particularly in water-stressed regions [21], [22]. The "food versus fuel" debate is another critical socio-economic consideration, as the use of food crops like maize for fuel can impact food prices and availability [23]. However, biofuel production can also be a powerful engine for rural development. In Zambia, cassava out-grower schemes have been shown to increase rural household incomes by 79%, creating jobs and stimulating local economies [5]. This aligns with findings from other developing nations where biofuel initiatives are seen as a tool to uplift vulnerable communities and reduce poverty.

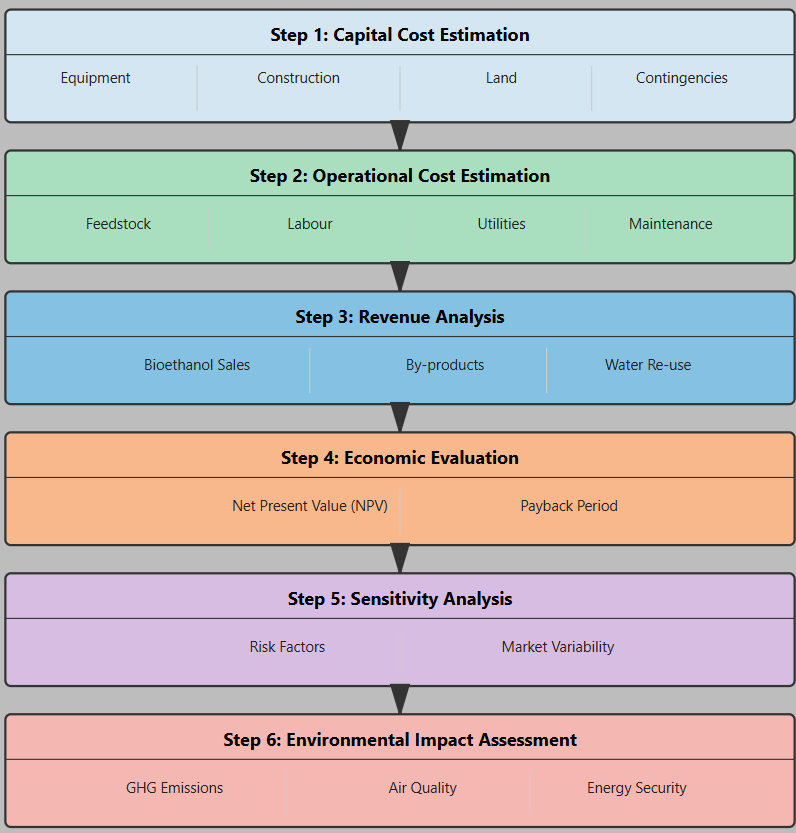

3. Methodology

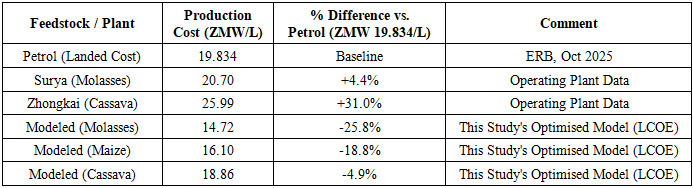

| Figure 1. Flowchart of the stepwise techno-economic analysis methodology used in this study |

3.1. Ethanol Plant Design and Process Flow

- The conceptual design for the 100,000 L/day ethanol facility was based on a modular configuration to allow for multi-feedstock flexibility [5]. The design incorporated dedicated processing lines for each feedstock before converging into a unified fermentation and distillation sequence. For maize, the process followed the dry-grind method, which includes grinding, slurry preparation, liquefaction, and simultaneous saccharification and fermentation (SSF) [26]. For cassava, the process involved washing, chipping, drying, and grinding, followed by enzymatic hydrolysis to convert starch into fermentable sugars [27]. The design for cassava also incorporated advanced technologies like on-farm chipping and pulsed electric field (PEF) treatment for cyanide reduction to mitigate rapid post-harvest spoilage. The molasses process flow was simpler, requiring only dilution and pH adjustment before fermentation, leveraging its readily available sugars [28]. The downstream process for all feedstocks included distillation to achieve a 95% ethanol concentration, followed by dehydration using molecular sieves to produce anhydrous ethanol (99.5%+ purity) suitable for fuel blending [29].

3.2. Economic Modeling Framework

- The economic viability of each feedstock pathway was evaluated using a Levelized Cost of Ethanol (LCOE) framework. The LCOE represents the average revenue per unit of ethanol produced that would be required to recover the costs of building and operating a production plant during an assumed financial life and duty cycle. It is calculated as the total lifecycle cost divided by the total lifetime ethanol production. The formula used is as follows:

| (1) |

represents the investment expenditures in year t,

represents the investment expenditures in year t,  represents the operations and maintenance expenditures in year t,

represents the operations and maintenance expenditures in year t,  is the fuel expenditures in year t,

is the fuel expenditures in year t,  is the ethanol generation in year t, r is the discount rate, and n is the life of the system. For this study, a discount rate of 10% and a project lifespan of 20 years were assumed, yielding an annuity factor of 8.514 [30]. Capital expenditure (CAPEX) estimates were based on 2024 supplier pricing for modular plants, while operating expenditure (OPEX) included costs for feedstock, energy, labor, water, and maintenance. Data were sourced from field trials at Zhongkai & Surya Energy, government agencies like the Energy Regulation Board (ERB), and industry stakeholders [5].

is the ethanol generation in year t, r is the discount rate, and n is the life of the system. For this study, a discount rate of 10% and a project lifespan of 20 years were assumed, yielding an annuity factor of 8.514 [30]. Capital expenditure (CAPEX) estimates were based on 2024 supplier pricing for modular plants, while operating expenditure (OPEX) included costs for feedstock, energy, labor, water, and maintenance. Data were sourced from field trials at Zhongkai & Surya Energy, government agencies like the Energy Regulation Board (ERB), and industry stakeholders [5].3.3. Data Collection, Uncertainty, and Sensitivity Analysis

- A mixed-methods approach was used for data collection. Quantitative data on production costs, feedstock prices, and fuel pricing trends were obtained from secondary sources, including the ERB, Zambia Agricultural Research Institute (ZARI), and industry reports. Qualitative data were gathered through semi-structured interviews with policymakers, industry experts, and agricultural specialists to understand the operational challenges and strategic opportunities.

3.3.1. Data Sources, Limitations, and Uncertainty

- Primary Data Limitations: Data from operational plants (Surya Biofuels, Zhongkai) were provided by plant management. While invaluable for establishing a real-world baseline, this data may be subject to commercial sensitivities and may not fully capture all operational inefficiencies. Furthermore, data from these specific plants may not be generalizable to the entire potential industry.Feedstock Price Volatility: Future prices of agricultural inputs, a key uncertainty, were modeled based on historical data from ZARI and the Central Statistical Office of Zambia. However, these prices are subject to significant volatility due to climate change impacts (droughts, floods), changes in government subsidy programs (e.g., Farmer Input Support Programme), and global commodity market fluctuations. This represents a primary source of uncertainty in the LCOE calculations.Model and Assumption Uncertainty: The techno-economic model relies on assumptions regarding plant efficiency, lifespan, and discount rates. While based on industry standards, actual performance can vary. The 10% discount rate reflects a mature market risk, which may be an optimistic assumption for a nascent industry in Zambia, where higher risk premiums could be expected by investors.

3.3.2. Sensitivity and Probabilistic Analysis

- To account for these market uncertainties, a Monte Carlo simulation (10,000 iterations) was performed as part of a sensitivity analysis. This probabilistic approach provides a more robust understanding of project risk than a simple deterministic analysis. The analysis assessed the impact of key variables, including feedstock price (±20% variance), exchange rate volatility (±15% variance), conversion efficiency (±10% variance), and agricultural input costs (e.g., fertilizer, ±25% variance) on the LCOE and overall economic viability of each pathway. This method allows for the generation of a probability distribution for the LCOE, rather than a single point estimate, offering policymakers a clearer picture of the potential range of outcomes and associated risks.

3.4. Environmental and Social Impact Assessment

- The environmental impact was assessed using a Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) framework, focusing on GHG emissions. The CML-IA methodology was employed to evaluate emissions across the entire production lifecycle, from feedstock cultivation to final combustion. The social impact assessment focused on job creation and income improvement, particularly for rural communities involved in out-grower schemes. Data for this assessment were drawn from reports by organizations like Musika and from stakeholder interviews, providing a qualitative and quantitative measure of the socio-economic co-benefits of biofuel development in Zambia [5].

4. Results and Analysis

- This section presents the core findings of the techno-economic analysis, directly addressing the research question regarding the impact of biofuel blending on petroleum fuel costs in Zambia. The analysis contrasts the performance of existing operational plants with the potential of optimised, large-scale facilities, using the pre-tax landed cost of petrol as a definitive benchmark.

4.1. Gasoline Cost Benchmark

- To accurately assess the economic competitiveness of domestically produced ethanol, a baseline for the cost of conventional petrol was established. Based on data from the Energy Regulation Board (ERB) for October 2025, the pre-tax landed cost of petrol is ZMW 19.834 per litre (approximately USD 0.861/L at an exchange rate of ZMW 23.03/USD). This figure represents the wholesale import cost before the application of domestic taxes, levies, and margins. It serves as the most relevant benchmark for comparing the production cost of a domestic substitute like ethanol, as it reflects the direct foreign exchange cost to the nation [5]. The tax-inclusive retail price, which averages ZMW 30.38/L, is less suitable for this comparison as it is heavily influenced by fiscal policy.

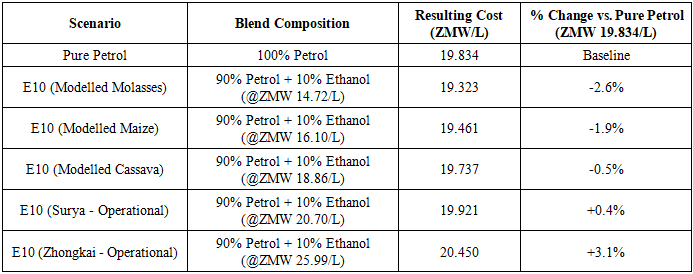

4.2. Comparative Analysis of Ethanol Production Costs

- A central finding of this study is the significant disparity between the production costs of existing biofuel plants in Zambia and the potential costs achievable with optimised, modern facilities. This gap between current reality and future potential is critical to understanding the challenges and opportunities for the sector.

4.2.1. Performance of Existing Operational Plants

- Data from operational plants provides a real-world snapshot of the industry's current state. The Surya Biofuels plant, which uses molasses, reports a production cost of ZMW 20.70 per litre. This is 4.4% more expensive than the pre-tax landed cost of petrol, indicating that current molasses-based production is not yet cost-competitive. The Zhongkai plant, which processes cassava, reports a much higher production cost of ZMW 25.99 per litre, a substantial 31.0% premium over imported petrol. This high cost reflects the significant logistical and technical hurdles associated with cassava, including its perishability and the energy-intensive nature of starch conversion [31]. These figures demonstrate that, under current operating conditions, biofuel production is not economically viable for blending without subsidies or significant efficiency improvements.

4.2.2. Levelized Cost of Ethanol (LCOE) from Optimised Models

- The techno-economic models developed in this study project a far more optimistic scenario, predicated on economies of scale and the adoption of advanced technologies. The LCOE for a new, optimised 100,000 L/day facility reveals a clear cost hierarchy among the feedstocks. Molasses-based ethanol emerges as the most cost-effective option, with a modelled LCOE of ZMW 14.72 per litre, representing a 25.8% cost saving compared to the petrol benchmark. This advantage is driven by the use of molasses as a low-cost byproduct, simplified pretreatment, and the ability to share infrastructure with existing sugar mills [32].Maize-based ethanol follows with a modelled LCOE of ZMW 16.10 per litre, an 18.8% saving against petrol. This competitiveness is contingent on achieving high conversion efficiencies (2.1 kg of maize per litre of ethanol) and generating revenue from byproducts like Distillers’ Dried Grains with Solubles (DDGS). Finally, the modelled LCOE for cassava-based ethanol is ZMW 18.86 per litre, a modest 4.9% saving. While the optimised model dramatically improves upon the performance of existing cassava plants, its competitiveness is still hampered by high transportation costs (45% of OPEX) and the crop's high perishability [33]. A summary of these cost comparisons is presented in Table 1 and Figure 2.

|

| Figure 2. Cost Comparison of Gasoline and Modeled Ethanol Types (Pre-Tax, ZMW/L) |

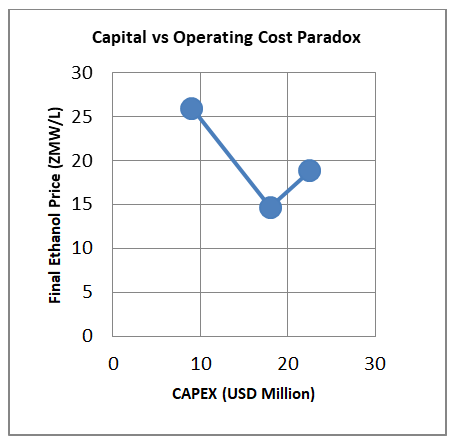

4.3. Capital and Operating Cost Dynamics

- The analysis of capital and operating costs reveals a "capital-operating cost paradox" in the Zambian context. Existing plants like Zhongkai, established with a relatively low reported CAPEX of USD 9 million (USD 0.60 per litre of annual capacity), exhibit very high operating costs, leading to an uncompetitive final ethanol price of ZMW 25.99/L. In contrast, the optimised models in this study assume a more realistic and higher CAPEX (USD 18-22.5 million) but achieve significantly lower operating costs and a competitive LCOE. This paradox highlights that underinvestment in efficient, modern technology during the capital phase leads to inflated long-term operational expenditures. For example, the modelled plants incorporate features like cogeneration from biogas and closed-loop water systems, which increase initial CAPEX but drastically reduce OPEX over the plant's lifespan. This underscores the lesson that focusing solely on minimizing upfront capital costs is a false economy for achieving sustainable and competitive biofuel production.

| Figure 3. The Capital vs. Operating Cost Paradox |

4.4. Economic Impact of E10 Blending

- The ultimate economic impact of ethanol is determined by its effect on the final price of blended fuel. This study evaluated the cost implications of a national 10% ethanol blend (E10). When blending with ethanol from existing, inefficient plants, the result is a price increase at the pump (pre-tax). Using ethanol from the Surya plant (ZMW 20.70/L) would increase the E10 blend cost by 0.4% over pure petrol, while using ethanol from the Zhongkai plant (ZMW 25.99/L) would lead to a 3.1% price hike.However, when using the LCOE values from the optimised models, the outcome is reversed. Blending with modelled molasses-based ethanol (ZMW 14.72/L) results in an E10 blend cost that is 2.6% cheaper than the pre-tax petrol price. Modelled maize and cassava ethanol also yield savings of 1.9% and 0.5%, respectively. These findings are pivotal, as they demonstrate that with the right investment in modern technology, E10 blending can lead to a reduction in the base cost of fuel.

|

4.5. Environmental and Socio-Economic Co-Benefits

- The study confirms that ethanol production in Zambia offers significant co-benefits. The lifecycle analysis shows that molasses-based ethanol can reduce GHG emissions by 45%, maize by 40%, and cassava by 35% compared to conventional petrol. These reductions are largely due to carbon sequestration during feedstock growth and the utilization of byproducts for energy generation [34].The social impact is equally profound. The development of a 100,000 L/day facility is projected to create approximately 180 direct jobs and up to 1,500 indirect jobs, primarily through smallholder farmer engagement. In the cassava value chain, out-grower schemes in the Luapula and Northern Provinces have increased average monthly household incomes by 79%, from ZMW 800 to ZMW 1,430. This injection of stable income into some of Zambia's poorest regions has a transformative effect on livelihoods, enabling investments in nutrition, education, and healthcare [35]. With women comprising 45% of participants in these schemes, the industry also promotes gender equity.

| Figure 4. Household Income Improvement in Northern Province Cassava Outgrower Scheme |

5. Discussion

- The findings of this study provide a multi-dimensional perspective on the viability of ethanol blending in Zambia, synthesizing economic, technical, environmental, and social assessments to chart a strategic pathway for the nation's biofuel industry. The results clearly indicate that while current production methods are economically uncompetitive, significant potential exists for cost savings and broader macroeconomic benefits through investment in modern, optimised facilities. This potential, however, is contingent on critical policy and fiscal reforms.

5.1. The Hierarchy of Feedstock Viability

- A distinct hierarchy of economic viability emerges among the three feedstocks. Molasses stands out as the most promising near-term option, with a modelled LCOE 25.8% below the landed cost of petrol. This powerful economic advantage stems from its status as a low-cost byproduct of Zambia’s established sugar industry, which eliminates the need for energy-intensive pretreatment and allows for co-location to share infrastructure. This positions molasses as the ideal feedstock to spearhead the initial scale-up of a national blending program.Maize represents a scalable but more sensitive alternative. Its potential 18.8% cost saving is attractive, but its viability is closely tied to managing feedstock price volatility and navigating the complex "food-versus-fuel" dilemma. Success with maize will depend on policies that promote sustainable agricultural intensification, such as the use of high-yield, drought-resistant varieties on existing farmland, rather than agricultural expansion. Cassava, with a marginal 4.9% cost saving in the optimised model, is not a primary candidate for driving down national fuel prices. However, its profound socio-economic impact in impoverished rural areas, where it has been shown to increase household incomes by 79%, positions it as a strategic tool for inclusive development. Its role is less about national cost reduction and more about targeted poverty alleviation, justifying specific policy support such as transport subsidies or investment in decentralized processing hubs.

5.2. Bridging the Gap: From Optimized Models to Practical Feasibility

- The "capital-operating cost paradox" and the identified technological bottlenecks are not merely technical issues; they are symptoms of a challenging investment climate and policy environment. The high OPEX of existing plants is a direct consequence of underinvestment in efficient technology, likely driven by policy uncertainty, high capital costs in the region, and a lack of access to affordable financing. Investors, faced with an unpredictable fiscal regime (e.g., the 60% excise duty), may opt for lower-CAPEX, higher-OPEX solutions to minimize upfront risk, inadvertently locking the industry into an uncompetitive state. Therefore, closing this feasibility gap is not just a matter of technical upgrades but requires a holistic strategy that de-risks investment in modern, efficient technology. This reinforces that policy is not just a downstream factor affecting the final price but a critical upstream determinant of technological choice and operational efficiency.

5.3. Policy as the Critical Enabler

- Ultimately, the success of biofuel blending in Zambia is a matter of policy, not just technology. The comparative analysis with Zimbabwe's E20 program starkly illustrates the prohibitive nature of Zambia’s current tax structure. A 60% excise duty and 16% VAT on ethanol completely negate any production cost advantage, making it impossible for the benefits of cheaper domestic fuel to reach consumers. This confirms that without fiscal reform, the government's stated objective of reducing fuel pump prices through blending is unattainable. The significant macroeconomic benefits, including USD 46.5 million in annual foreign exchange savings, enhanced energy security, and the creation of thousands of rural jobs, provide a compelling rationale for the government to create a more favorable policy environment. As research on other developing economies shows, a stable, long-term, and supportive policy framework is the single most important factor in attracting the private investment needed to build a competitive bioenergy sector.

6. Conclusions and Strategic Recommendations

- This study has comprehensively evaluated the technical, economic, environmental, and social viability of ethanol production and blending in Zambia. The central conclusion is that while ethanol blending is technically feasible and offers substantial environmental and social co-benefits, its economic viability is critically dependent on strategic investment in modern, efficient production facilities and, most importantly, on targeted policy interventions. The current state of the industry, characterized by inefficient operations and prohibitive tax structures, prevents the realization of biofuel's potential. However, a clear, data-driven pathway exists for Zambia to develop a sustainable and competitive domestic biofuel sector.The analysis reveals a significant gap between the high costs of current operations and the promising economics of optimised production. With a petrol landed cost of ZMW 19.834/L, optimised ethanol from molasses (ZMW 14.72/L), maize (ZMW 16.10/L), and even cassava (ZMW 18.86/L) can be produced at a cost below that of imported fuel. This cost advantage, if translated to the pump, could fulfill the government's goal of lowering fuel prices. Furthermore, a national E10 mandate offers profound macroeconomic benefits, including an estimated USD 46.5 million in annual foreign exchange savings, enhanced energy security, and the creation of thousands of rural jobs. To unlock this potential, the following synthesized and enhanced recommendations are proposed.

6.1. Strategic Recommendations

- Based on these conclusions, the following strategic recommendations are proposed to unlock the potential of Zambia's biofuel sector, in alignment with the Eighth National Development Plan (8NDP).

6.1.1. Fiscal and Market Reform

- The most immediate and impactful policy intervention required is fiscal reform. The government should introduce a preferential tax regime for domestically produced ethanol.Tax Reduction and Exemption: It is recommended to reduce the excise duty on the ethanol portion of blended fuels from 60% to a nominal rate (or zero) and provide a full VAT exemption. This policy must be carefully designed to apply only to domestically produced ethanol, verified through a certification and tracking system managed by ZRA and ERB, to stimulate local industry without creating loopholes for imports.Implementation Mechanism: The tax differential should be applied at the wholesale level where blending occurs (e.g., at the Indeni refinery or major fuel depots). This ensures the cost reduction is embedded in the wholesale price passed to Oil Marketing Companies (OMCs), making it more likely to be reflected at the pump.Investment Incentives: To address the "capital-operating cost paradox," the government should offer investment-focused fiscal incentives. This could include accelerated depreciation allowances for biofuel plants and equipment, and duty-free importation of critical, modern technologies (e.g., high-efficiency distillation columns, molecular sieves, advanced process control systems). Such incentives directly lower the CAPEX barrier and encourage investment in efficiency.

6.1.2. Feedstock-Specific Support Pathways

- Policy should be tailored to the unique characteristics of each feedstock.For Molasses: As the most economically competitive pathway, policy should focus on streamlining regulations and offering investment tax credits for sugar estates to invest in co-located distilleries that valorise byproducts.For Maize: Policy must mitigate price volatility and food security concerns by promoting high-yield, drought-resistant varieties and strengthening contract farming arrangements. A portion of the national strategic food reserve could be allocated for biofuel during years of surplus to stabilize prices.For Cassava: Its strategic role in rural development justifies targeted interventions, such as subsidies for transportation from remote areas and public investment in decentralized chipping and processing hubs in the Northern and Luapula provinces. This would reduce the logistical burden on a central plant and create more localized economic activity.

6.1.3. Investment in Infrastructure and Technology

- Government policy must facilitate investment to close infrastructure and technology gaps.Public-Private Partnerships (PPPs): The government should actively pursue PPPs to upgrade rural road networks in key feedstock-producing areas, and to expand blending and storage infrastructure at national fuel depots.Technology Transfer and R&D Fund: To address the operational efficiency gap, the government could establish a technology transfer fund. This fund could co-finance the adoption of modern process control systems, energy-efficient equipment, and advanced yeast strains developed by institutions like ZARI, providing grants or low-interest loans to plants committed to efficiency upgrades.

6.1.4. Phased Implementation of Blending Mandates

- A phased and realistic implementation of blending mandates is recommended. The government should begin by enforcing an E10 mandate, which can be met in the short term by expanding cost-effective molasses-based production. As the production of maize and cassava ethanol becomes more efficient and scalable, the mandate can be progressively increased to E15 or E20. This gradual approach will allow the industry to develop capacity sustainably, avoid supply shocks, and build consumer confidence, with the ERB playing a proactive role in ensuring strict quality control.

6.2. Future Research Directions

- To support the long-term growth of the sector, future research should prioritize:Feedstock Optimization: Research into hybrid maize-cassava intercropping systems and the exploration of alternative, non-food feedstocks like sweet sorghum and lignocellulosic biomass (e.g., corn stover).Advanced Blending Technologies: Studies on material compatibility and engine performance for higher blends like E20 and E85 are vital to ensure seamless integration with Zambia's existing vehicle fleet and fuel infrastructure.Socio-Economic Impact Analysis: Detailed, gender-disaggregated socio-economic impact analyses should be undertaken to quantify the benefits of out-grower schemes and inform policies that maximize inclusive growth and ensure benefits are equitably distributed.By adopting this integrated strategy, Zambia can transform its biofuel potential into a cornerstone of its energy security, economic growth, and environmental stewardship.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- I would like to express my profound gratitude to all individuals and institutions whose support made this research possible. My deepest appreciation goes to my supervisor, Professor Yamba, for his invaluable guidance, constructive criticism, and unwavering encouragement throughout this research journey. His expertise and insights were instrumental in shaping this dissertation. I extend my sincere thanks to the University of Zambia, particularly the Department of Mechanical Engineering and the School of Engineering, for providing the academic environment and resources necessary for this research. I am grateful to the Energy Regulation Board (ERB) of Zambia for providing access to crucial data on petroleum pricing and industry standards. My appreciation also extends to Zhongkai, Zambia Sugar, and other industry stakeholders who shared their expertise and allowed access to their facilities during the data collection phase. I acknowledge with gratitude the contributions of the Zambia Agricultural Research Institute (ZARI) and the National Water Supply and Sanitation Council (NWASCO) for their technical support and data provision that enriched this research. To my colleagues and fellow researchers who participated in discussions and provided valuable feedback, I offer my heartfelt thanks. Finally, I am deeply indebted to my family for their patience, understanding, and moral support throughout this academic pursuit.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML