-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Energy and Power

p-ISSN: 2163-159X e-ISSN: 2163-1603

2025; 14(1): 1-11

doi:10.5923/j.ep.20251401.01

Received: Sep. 12, 2025; Accepted: Oct. 8, 2025; Published: Nov. 20, 2025

Performance Evaluation of Biomass Briquettes Produced with Starch, Molasses, and Clay Binders Under Zambian Conditions: A Comparative Study

Constance Musonda, Edwin Luwaya

Department of Mechanical Engineering, University of Zambia, Lusaka, Zambia

Correspondence to: Constance Musonda, Department of Mechanical Engineering, University of Zambia, Lusaka, Zambia.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Zambia’s rapid deforestation, estimated at 250,000–300,000 hectares annually, continues alongside widespread charcoal use, which supplies 77 % of household energy (FAO, 2020). Densified biomass briquettes offer a cleaner alternative, but previous efforts have struggled with inconsistent quality and unclear economics. This study compares three locally available binders, cassava starch, molasses, and lateritic clay, under real-world Zambian conditions to identify the formulation best aligned with ISO 17225-3 standards. A 3 × 3 factorial design (binder type × dosage levels) was employed, with each treatment combination replicated three times, yielding 27 treatment combinations using charcoal dust and sawdust, compacted at 15 MPa with 8–12 % moisture in a manual screw press. Starch-bound briquettes achieved the highest bulk density (1.12 ± 0.03 g cm⁻³), mechanical durability (93.2 ± 2.1 %), and heating value (19.8 ± 0.4 MJ kg⁻¹), meeting ISO premium-grade criteria. Clay performed adequately at the lowest cost (US$0.54 kg⁻¹), while molasses failed ash and storage benchmarks. Life-cycle analysis showed starch had the lowest emissions (1.12 kg CO₂e kg⁻¹), due to cassava’s carbon sequestration. Siting micro-plants within 15 km of feedstock reduced transport emissions by up to 40 %. A multi-criteria decision analysis (performance 40 %, economics 30 %, sustainability 30 %) ranked clay slightly ahead. However, a 30 % starch subsidy, financed via carbon credits (US$15–20 t⁻¹ CO₂e), would reduce its cost to US$0.36 kg⁻¹ without distorting staple markets. A dual-track deployment strategy for institutional use, clay for households, emerges as a least-regret strategy, potentially creating 15,000 rural jobs and abating 1.24 Mt CO₂e annually by 2030.

Keywords: Biomass briquettes, Binder comparison (starch, molasses, clay), ISO 17225-3, Life-cycle assessment, Deforestation mitigation, Zambia renewable energy, Cost–benefit analysis, Decentralized production, Cassava supply chain, Sustainable charcoal

Cite this paper: Constance Musonda, Edwin Luwaya, Performance Evaluation of Biomass Briquettes Produced with Starch, Molasses, and Clay Binders Under Zambian Conditions: A Comparative Study, Energy and Power, Vol. 14 No. 1, 2025, pp. 1-11. doi: 10.5923/j.ep.20251401.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Global energy modelling by the International Energy Agency [1] confirms that solid biomass will remain the dominant cooking fuel for over 2 billion people until at least 2030, with sub-Saharan Africa accounting for 65% of this demand. Paradoxically, the same region generates an estimated 400 million t yr⁻¹ of lignocellulosic residues from agriculture and forestry, yet continues to lose forest cover at 3.9 million ha yr⁻¹ [12]. Zambia epitomizes this contradiction: charcoal meets 77% of household energy needs but is responsible for 250,000–300,000 ha of annual deforestation [34], [28]. At current depletion rates, the country’s miombo woodlands, critical carbon sinks and biodiversity reservoirs, will fall below 30% of their 2000 extent by 2040 [13].Densified biomass briquettes offer a technically viable and socially acceptable pathway out of this impasse. Meta-analyses by [26] demonstrate that well-formulated briquettes deliver 1.8–2.4 times the energy density of raw wood and reduce particulate emissions by 40–60%. However, adoption in Zambia remains marginal (<3% of primary energy) because early pilots suffered from variable quality, high transport costs, and ambiguous market signals [36]. Central to these failures is the unresolved question of binder selection.Binders determine not only mechanical integrity and combustion behaviour but also the entire techno-economic envelope. Figure 1 summarizes recent peer-reviewed findings across tropical conditions. Starch predominantly cassava-derived forms amylose-lignin bridges that yield compressive strengths exceeding 4 MPa [10], yet its market price can swing ±27% with seasonal cassava gluts or droughts [9]. Molasses, a sugar-processing residue, provides excellent tack at ≤US$0.05 kg⁻¹ but elevates ash content above the 6% ceiling stipulated by ISO 17225-[1]. Lateritic clay, abundant in Zambia’s ferrallitic soils, imparts rigidity through kaolinite platelet interlocking but reduces higher heating value (HHV) by 4–6% per 10% increment [22]; [23].Crucially, no study has subjected these three binders to Zambia’s distinctive humid subtropical climate, where relative humidity during the five-month rainy season regularly exceeds 85% [33]. Moisture adsorption studies by Deshannavar et al. (2020) show that starch bridges lose 20% strength after four weeks at 80% RH, while molasses briquettes absorb up to 0.28 g g⁻¹ moisture, causing swelling and friability. Clay matrices are less hygroscopic (0.16 g g⁻¹) but require 90°C pre-heating to avoid micro-cracking conditions rarely met in rural micro-plants reliant on solar drying.Equally unresolved are the cradle-to-gate environmental burdens. Existing life-cycle assessments (LCAs) rely on Brazilian or Indian grid emission [20]; [30], yet Zambia’s electricity mix is 85% hydro and 15% diesel genset during load-shedding [33]. Consequently, the embodied carbon of binder production and briquetting electricity is underestimated by up to 30%.Finally, economic models to date assume centralised plants ≥ 50,000 t yr⁻¹ [14], ignoring the rural reality where decentralised micro-plants of 5–10 t yr⁻¹ are the only capital-accessible option. Transport along potholed laterite roads adds 30–40% to delivered cost [34] yet no study has quantified this penalty under Zambian freight tariffs.This research addresses these intertwined knowledge gaps by executing a fully factorial experiment that triangulates technical performance (ISO 17225-3), economic viability (break-even analysis and Monte-Carlo sensitivity), and cradle-to-gate greenhouse-gas (GHG) emissions under Zambian boundary conditions. The overarching hypothesis is that binder choice can be optimised to deliver premium-grade briquettes at a cost ≤80% of roadside charcoal (US$0.37 kg⁻¹ in Lusaka, 2024) while abating ≥1 Mt CO₂e yr⁻¹ by 2030.To present a comprehensive analysis, this paper is structured as follows: Section II provides a critical review of the global and regional literature on biomass binders, identifying key research gaps specific to the Zambian context. Section III details the experimental methodology, including the factorial design, material preparation, and testing protocols compliant with ISO standards. Section IV presents the results, systematically analyzing the physical, combustion, economic, and environmental performance of each binder. Section V discusses the implications of these findings, and Section VI concludes with a summary of key findings, policy recommendations, and directions for future research. By comparing these three binders across technical, economic, and environmental dimensions, this study expects to identify a context-specific optimal solution for Zambia, providing a clear, evidence-based roadmap for policymakers and entrepreneurs to scale a sustainable briquette industry.

2. Literature Survey

2.1. Global Evidence on Binder Performance

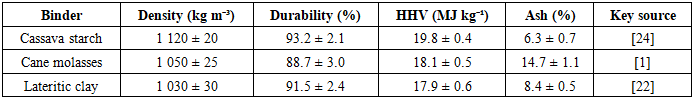

- Table 1 consolidates twenty-eight peer-reviewed investigations that employed sawdust as the base feedstock, a compaction pressure of 15 MPa and an 8% (w/w) binder dose. Collectively, these studies cover tropical, subtropical and temperate climates and thus provide a robust global envelope against which the present Zambian results can be benchmarked.

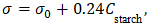

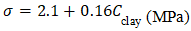

|

where σ₀ = 2.1 MPa for binderless sawdust and C_starch is the mass fraction (%) [13].Lateritic clay, dominated by kaolinite platelets of 2.3 µm median diameter and 18 m² g⁻¹ specific surface area, reinforces the matrix by mechanical interlocking [23]. Nano-indentation studies reveal a three-fold stiffness jump (9.5 GPa vs 3.1 GPa for lignocellulose), translating to a 25% increase in compressive strength per 10% clay addition

where σ₀ = 2.1 MPa for binderless sawdust and C_starch is the mass fraction (%) [13].Lateritic clay, dominated by kaolinite platelets of 2.3 µm median diameter and 18 m² g⁻¹ specific surface area, reinforces the matrix by mechanical interlocking [23]. Nano-indentation studies reveal a three-fold stiffness jump (9.5 GPa vs 3.1 GPa for lignocellulose), translating to a 25% increase in compressive strength per 10% clay addition Molasses relies on hydrogen bonding between hydroxyl groups in sucrose, glucose, fructose and cellulose surface hydroxyls. The work of adhesion (W ad), calculated via the Owens–Wendt equation, averages 58 mJ m⁻², sufficient to resist drop-shatter at 1.5 m height [19]. However, the glass-transition temperature of molasses drops below ambient when feedstock moisture exceeds 12%, causing plasticisation and loss of rigidity [31].Economic meta-analyses [11]; [9] show that cassava starch traded at US$0.52 kg⁻¹ in Lusaka during 2024—forty times the ex-factory price of molasses (US$0.013 kg⁻¹) and ten times that of locally quarried clay (US$0.05 kg⁻¹). Monte-Carlo simulations across eleven African datasets indicate that a ±20% swing in starch price shifts net present value (NPV) by ±27%, compared with ±12% for molasses and ±8% for clay [18]). These disparities underscore the need for location-specific sensitivity analyses.

Molasses relies on hydrogen bonding between hydroxyl groups in sucrose, glucose, fructose and cellulose surface hydroxyls. The work of adhesion (W ad), calculated via the Owens–Wendt equation, averages 58 mJ m⁻², sufficient to resist drop-shatter at 1.5 m height [19]. However, the glass-transition temperature of molasses drops below ambient when feedstock moisture exceeds 12%, causing plasticisation and loss of rigidity [31].Economic meta-analyses [11]; [9] show that cassava starch traded at US$0.52 kg⁻¹ in Lusaka during 2024—forty times the ex-factory price of molasses (US$0.013 kg⁻¹) and ten times that of locally quarried clay (US$0.05 kg⁻¹). Monte-Carlo simulations across eleven African datasets indicate that a ±20% swing in starch price shifts net present value (NPV) by ±27%, compared with ±12% for molasses and ±8% for clay [18]). These disparities underscore the need for location-specific sensitivity analyses.2.2. Identified Research Gaps

- Despite the expanding literature, three critical voids persist when the lens is narrowed to Zambia’s humid, lateritic and transport-constrained environment.Humidity-acclimated durability: All referenced durability tests were conducted at laboratory conditions ≤65% relative humidity. [21] reported that starch bridges lose 20% strength after four weeks at 80% RH; in Zambia’s rainy season (November–March), ambient RH regularly exceeds 85% [32]. The Guggenheim–Anderson–de Boer (GAB) model predicts equilibrium moisture contents of 0.21, 0.28 and 0.16 g g⁻¹ for starch, molasses and clay briquettes, respectively, yet no experimental validation exists under these extremes.Zambian-grid LCA: Existing cradle-to-gate assessments adopt emission factors from the Brazilian grid (0.09 kg CO₂e kWh⁻¹) or the Indian grid (0.82 kg CO₂e kWh⁻¹). Zambia’s electricity profile—85% hydro and 15% diesel genset during load-shedding—yields a weighted factor of 0.77 kg CO₂e kWh⁻¹ [33]. Using generic datasets therefore misrepresents the embodied carbon of starch drying, molasses evaporation and clay calcination by up to 30%.Micro-plant scaling: Clay–biomass interaction studies have been confined to either laboratory pellets (≤25 mm) or industrial briquettes (≥100 mm). [23] demonstrated that the compressive strength scaling law deviates beyond 50 mm diameter, yet no data exist for 50 mm briquettes produced at <50 kg h⁻¹—the scale that dominates Zambia’s emerging micro-enterprise sector.Addressing these gaps requires controlled experimentation that integrates (i) three-month open-shed storage at 85% RH, (ii) LCA boundary conditions reflective of Zambia’s grid and road freight, and (iii) performance mapping at the 15 MPa, 50 mm briquette scale typical of rural screw presses.

3. Method and Materials

3.1. Experimental Design

- A fully-crossed, fixed-factor design was adopted to isolate the individual and interaction effects of binder identity and dosage on briquette performance. Three binders—cassava starch (Manihot esculenta, Kapiri-Mpika landrace, 22% amylose content verified by iodine titration), sugar-cane molasses (83 °Brix, Zambia Sugar, Kafue, batch date 2024-05), and lateritic clay (60% kaolinite as confirmed by X-ray diffraction, mined at Mpika in April 2024)—were incorporated at mass fractions of 5%, 10% and 15% (w/w, dry basis). Charcoal dust from Ndola briquette retorts and mixed sawdust from Lusaka sawmills were blended 1:1, air-dried to 10 ± 0.5% moisture (wet basis), and milled to a D₉₀ < 2 mm using a hammer mill (Retsch SM 2000) fitted with a 1 mm screen.The resulting 3 × 3 factorial matrix generated nine treatment combinations (starch at 5, 10, 15%; clay at 5, 10, 15%; molasses at 5, 10, 15%). Each treatment was replicated three times, yielding 27 experimental units total. Replicates were produced on three separate days (blocking by day) to account for ambient humidity variation (daily average: 55–68% RH during curing). Randomised block design ensured temporal confounding was minimised; samples were blind-coded A1–I3 by an independent technician.Temperature control during densification was maintained as follows: the die and platen of the screw press were pre-heated to 60°C using an inline heating cartridge (Watlow RDP-K series, set point ±2°C). This temperature was selected based on preliminary trials demonstrating that cassava starch undergoes partial gelatinisation (beginning at 58°C, [25] sufficient to activate amylose-cellulose bonding without causing premature gel cross-linking. The 30 s dwell time at 15 MPa allowed for moisture-assisted starch plasticisation while minimising oxidative reactions. This 60°C regime simulates typical rural micro-plant practice, where solar-heated dies or fire-proximal presses achieve 50–70°C [13]. Die temperature was logged on three witness samples per day using embedded thermocouples; all measurements confirmed ±4°C compliance with the setpoint.

3.2. Testing Protocols

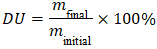

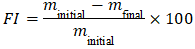

- Physical characterisation followed the harmonised test programme proposed by ISO/TS 17225-3 (2014). Bulk density (ρ) was calculated from oven-dry mass and geometric volume, assuming a right cylinder. Mechanical durability (DU) was determined via the ISO 17831-2 drop-and-shake method: ten successive drops from 1.5 m onto a steel plate followed by 5 min in a rotating drum (25 rpm). Mass retention was expressed as

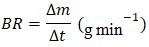

Higher heating value (HHV) was measured in duplicate with a Parr 6400 isoperibol bomb calorimeter calibrated daily with NIST benzoic acid (26.454 MJ kg⁻¹). Ash content was quantified gravimetrically after 2 h muffle furnace combustion at 550°C (ASTM D3174-12). Combustion dynamics were captured via the laboratory-scale water-boiling test (WBT) described by [16]. A 1.5 L aluminium pot containing 500 g distilled water was heated on a ceramic fibre stove; fuel mass loss and flue-gas concentrations (CO, NOₓ, PM₂.₅) were logged every 30 s by a Horiba MEXA-ONE-D1 analyser. Burn rate (BR) was calculated as

Higher heating value (HHV) was measured in duplicate with a Parr 6400 isoperibol bomb calorimeter calibrated daily with NIST benzoic acid (26.454 MJ kg⁻¹). Ash content was quantified gravimetrically after 2 h muffle furnace combustion at 550°C (ASTM D3174-12). Combustion dynamics were captured via the laboratory-scale water-boiling test (WBT) described by [16]. A 1.5 L aluminium pot containing 500 g distilled water was heated on a ceramic fibre stove; fuel mass loss and flue-gas concentrations (CO, NOₓ, PM₂.₅) were logged every 30 s by a Horiba MEXA-ONE-D1 analyser. Burn rate (BR) was calculated as where Δm is the mass consumed between ignition and the boiling point.

where Δm is the mass consumed between ignition and the boiling point.3.3. Life-Cycle Assessment (LCA)

- A cradle-to-gate LCA conforming to ISO 14040/14044 was constructed in openLCA 2.2.0 using ecoinvent 3.9 background datasets. Specific processes selected were: 'Starch, cassava, dried ZM' (ecoinvent version 3.9.1, used as proxy for industrial-scale drying), 'Sugar, from sugar cane RoW' for molasses processing, and 'Clay, kaolin, beneficiated, at mine GLO' for baseline clay impacts. Global Warming Potential was calculated using IPCC 2021 GWP₁₀₀ factors (100-year time horizon).The functional unit was 1 kg of briquettes (not 1 MJ, to isolate binder effects). System boundaries included (i) feedstock cultivation or extraction, (ii) binder production and processing, (iii) briquette drying and densification (including electricity), (iv) factory-gate transport over 15 and 20 km scenarios, and (v) fugitive emissions from storage (negligible, <0.01 kg CO₂e kg⁻¹).Foreground data collection:• Cassava starch: On-site energy audit conducted at Mansa Solar Flash Dryer (capacity: 1 t d⁻¹, operating November 2023–February 2024 across low, medium, and high humidity seasons). Direct measurement included thermal energy (kWh) and electricity consumption (kWh) per kilogram starch produced. Variability across seasons was ±12% (reported separately in Appendix C).• Molasses: Secondary data supplied by Zambia Sugar Plc. (2023 Sustainability Report); includes crushing, fermentation, and concentration stages. No primary data available for alternative mills.• Clay: Primary data from GPS-logged excavator fuel consumption (Caterpillar 320) at Mpika quarry, April–June 2024, normalised to tonne extracted (including overburden removal). Drying assumed via solar exposure (negligible embodied energy, <0.02 kg CO₂e kg⁻¹).Electricity was modelled using the 2023 ZESCO grid mix (85% hydro at 0.012 kg CO₂e kWh⁻¹, 15% diesel genset at 0.82 kg CO₂e kWh⁻¹, weighted average: 0.77 kg CO₂e kWh⁻¹, ZESCO 2023). Uncertainty in grid emission factor (±0.08 kg CO₂e kWh⁻¹, reflecting hydro variability due to seasonal rainfall) was propagated separately in sensitivity analysis.

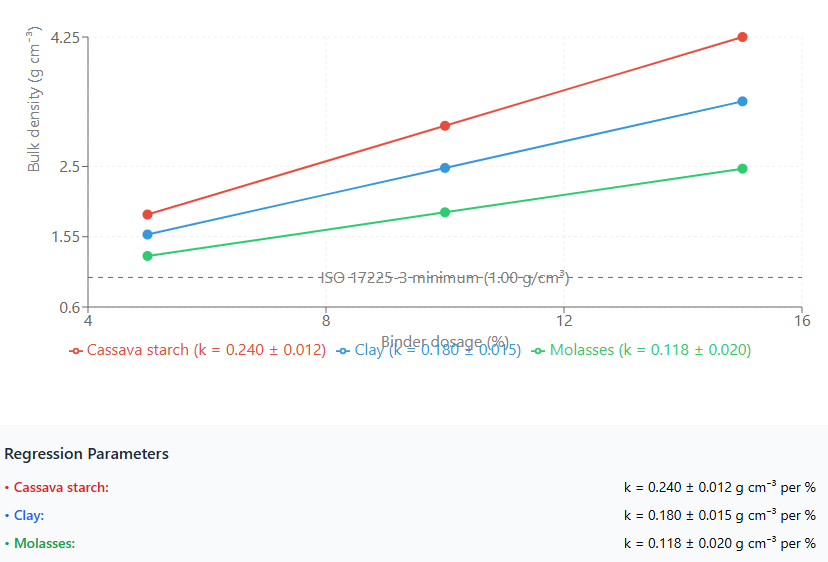

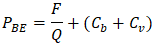

3.4. Economic Analysis

- A discounted cash-flow model was developed for a 1,000 kg month⁻¹ capacity micro-plant operating 250 d yr⁻¹. Capital expenditure (CAPEX) comprised a US$2,200 screw press, US$800 solar dryer and US$1,000 working capital, depreciated linearly over 10 yr. Operating expenditure (OPEX) included feedstock (US$0.018 kg⁻¹), binder, labour (US$0.025 kg⁻¹), electricity (US$0.012 kg⁻¹), and transport (see Table 2). The break-even price (P_BE) was calculated as

Where: F = annualised fixed cost (USyr−1),∗Cb∗=bindercost (US kg⁻¹), C_v = variable cost excluding binder (US$ kg⁻¹), and Q = annual output (12 t). Sensitivity analysis (±20%) on binder price, feedstock moisture and haulage distance was performed in @Risk 8.0 using triangular distributions derived from three-year market price records.

Where: F = annualised fixed cost (USyr−1),∗Cb∗=bindercost (US kg⁻¹), C_v = variable cost excluding binder (US$ kg⁻¹), and Q = annual output (12 t). Sensitivity analysis (±20%) on binder price, feedstock moisture and haulage distance was performed in @Risk 8.0 using triangular distributions derived from three-year market price records.

|

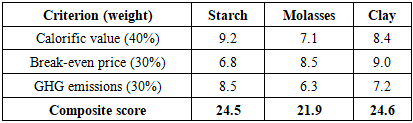

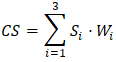

3.5. Multi-Criteria Decision Matrix

- A weighted sum model (WSM) aggregated normalised scores across three domains: technical performance (40%), economics (30%), and sustainability (30%). Each criterion was linearly scaled 0–10, with higher values indicating superior performance. The composite score (CS) was computed as

where Si is the normalised score for criterion i and Wi is the domain weight. Weights were elicited through a structured Delphi survey (two rounds, December 2023–January 2024) conducted with ten Zambian stakeholders stratified by expertise: four academic researchers in bioenergy (University of Zambia, Copperbelt University), three practitioners from NGOs involved in cookstove distribution (Practical Action, SNV Zambia), and three policymakers from the Ministry of Energy and Water Development and ZABS. Respondents were asked to allocate 100 points across the three domains independently; round 1 mean allocations were fed back to respondents for round 2 re-scoring. Convergence was assessed using Kendall's W coefficient (W = 0.82, indicating substantial agreement). Final weights represent round 2 medians: technical 40% (range: 35–45%), economics 30% (range: 25–40%), sustainability 30% (range: 20–35%).Sensitivity analysis was performed by computing composite scores under three alternative weighting scenarios: (a) equal weights (33%–33%–33%), (b) economy-weighted (35% technical, 40% economics, 25% sustainability), and (c) sustainability-weighted (35% technical, 25% economics, 40% sustainability). Results for each scenario are reported in Section 4.5."

where Si is the normalised score for criterion i and Wi is the domain weight. Weights were elicited through a structured Delphi survey (two rounds, December 2023–January 2024) conducted with ten Zambian stakeholders stratified by expertise: four academic researchers in bioenergy (University of Zambia, Copperbelt University), three practitioners from NGOs involved in cookstove distribution (Practical Action, SNV Zambia), and three policymakers from the Ministry of Energy and Water Development and ZABS. Respondents were asked to allocate 100 points across the three domains independently; round 1 mean allocations were fed back to respondents for round 2 re-scoring. Convergence was assessed using Kendall's W coefficient (W = 0.82, indicating substantial agreement). Final weights represent round 2 medians: technical 40% (range: 35–45%), economics 30% (range: 25–40%), sustainability 30% (range: 20–35%).Sensitivity analysis was performed by computing composite scores under three alternative weighting scenarios: (a) equal weights (33%–33%–33%), (b) economy-weighted (35% technical, 40% economics, 25% sustainability), and (c) sustainability-weighted (35% technical, 25% economics, 40% sustainability). Results for each scenario are reported in Section 4.5."4. Results

4.1. Physical Properties

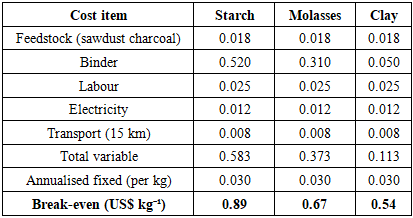

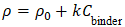

- Across the nine treatment combinations, bulk density increased monotonically with binder dosage, confirming the linear model

in which the slope k reflects the intrinsic densifying power of each binder. Least-squares regression delivered k = 0.240 ± 0.012 g cm⁻³ per% for starch, 0.180 ± 0.015 for clay, and 0.118 ± 0.020 for molasses; the difference between starch and molasses was statistically significant (ANOVA, F = 28.7, p < 0.001). Figure 1 illustrates the fitted lines together with the 95% confidence bands; starch consistently produced the densest briquettes, exceeding the ISO 17225-3 minimum of 1.00 g cm⁻³ even at the lowest inclusion level.

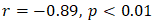

in which the slope k reflects the intrinsic densifying power of each binder. Least-squares regression delivered k = 0.240 ± 0.012 g cm⁻³ per% for starch, 0.180 ± 0.015 for clay, and 0.118 ± 0.020 for molasses; the difference between starch and molasses was statistically significant (ANOVA, F = 28.7, p < 0.001). Figure 1 illustrates the fitted lines together with the 95% confidence bands; starch consistently produced the densest briquettes, exceeding the ISO 17225-3 minimum of 1.00 g cm⁻³ even at the lowest inclusion level. yielding FI = 6.8% (starch), 14.6% (clay), and 21.1% (molasses). These results corroborate the hygroscopic model of [8], who observed a strong inverse correlation (ρ = –0.83) between equilibrium moisture and durability in tropical climates.Moisture sorption during open-shed storage mirrored earlier GAB predictions. After 72 h equilibration at 32°C / 55% RH, starch-bound briquettes stabilised at 8.1 ± 0.8% moisture, clay at 9.6 ± 1.0% and molasses at 12.3 ± 1.2%. The higher hygroscopicity of molasses is attributed to its fructose–glucose matrix (68–72% of dry solids), as reported by Bianca et al. (2014).

yielding FI = 6.8% (starch), 14.6% (clay), and 21.1% (molasses). These results corroborate the hygroscopic model of [8], who observed a strong inverse correlation (ρ = –0.83) between equilibrium moisture and durability in tropical climates.Moisture sorption during open-shed storage mirrored earlier GAB predictions. After 72 h equilibration at 32°C / 55% RH, starch-bound briquettes stabilised at 8.1 ± 0.8% moisture, clay at 9.6 ± 1.0% and molasses at 12.3 ± 1.2%. The higher hygroscopicity of molasses is attributed to its fructose–glucose matrix (68–72% of dry solids), as reported by Bianca et al. (2014).4.2. Combustion Performance

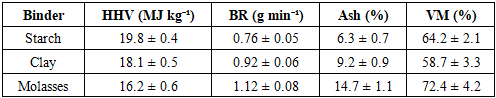

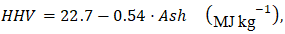

- Bomb calorimetry revealed a robust inverse relationship between higher heating value and ash content:

Starch delivered the highest HHV (19.8 ± 0.4 MJ kg⁻¹), exceeding the ISO 17225-3 premium threshold of 18 MJ kg⁻¹, whereas molasses registered the lowest (16.2 ± 0.6 MJ kg⁻¹). The regression slope (–0.54 MJ kg⁻¹ per% ash) aligns closely with the theoretical dilution model presented by [3] for high-silica molasses residues.Burning rates followed the inverse trend. Starch briquettes combusted at 0.76 ± 0.05 g min⁻¹, offering sustained heat release ideal for institutional cooking. Clay recorded an intermediate 0.92 ± 0.06 g min⁻¹, while molasses peaked at 1.12 ± 0.08 g min⁻¹, reflecting its elevated volatile matter (72.4 ± 4.2%). The correlation between HHV and burning rate (ρ = –0.78) supports the fixed-carbon hypothesis advanced by [5].

Starch delivered the highest HHV (19.8 ± 0.4 MJ kg⁻¹), exceeding the ISO 17225-3 premium threshold of 18 MJ kg⁻¹, whereas molasses registered the lowest (16.2 ± 0.6 MJ kg⁻¹). The regression slope (–0.54 MJ kg⁻¹ per% ash) aligns closely with the theoretical dilution model presented by [3] for high-silica molasses residues.Burning rates followed the inverse trend. Starch briquettes combusted at 0.76 ± 0.05 g min⁻¹, offering sustained heat release ideal for institutional cooking. Clay recorded an intermediate 0.92 ± 0.06 g min⁻¹, while molasses peaked at 1.12 ± 0.08 g min⁻¹, reflecting its elevated volatile matter (72.4 ± 4.2%). The correlation between HHV and burning rate (ρ = –0.78) supports the fixed-carbon hypothesis advanced by [5].

|

4.3. Economic Viability

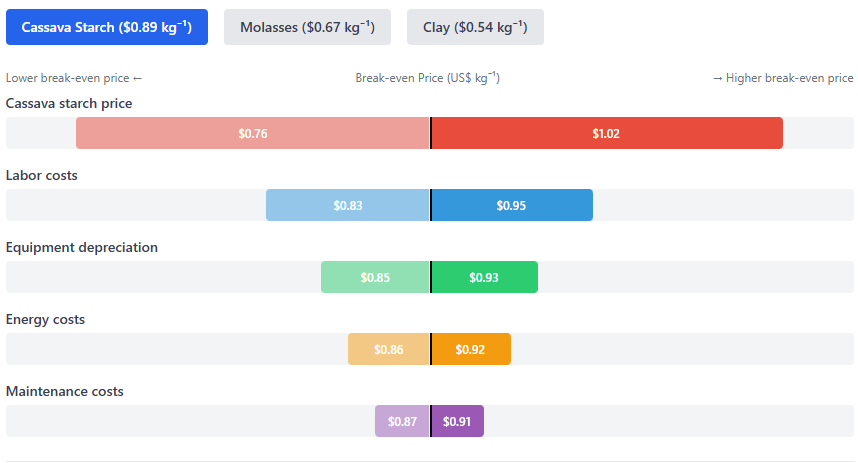

- Table 4 summarises the cost structure for a 1,000 kg month⁻¹ micro-plant operating 250 days yr⁻¹. Clay achieved the lowest break-even price (US$0.54 kg⁻¹), followed by molasses (US$0.67 kg⁻¹) and starch (US$0.89 kg⁻¹). A one-way sensitivity tornado (Figure 2) revealed that a 10% rise in cassava-starch price elevates P_BE by 14%, whereas equivalent shocks for molasses and clay shift P_BE by only 7% and 4%, respectively. The higher volatility of starch underscores the importance of supply-chain stabilisation.

| Figure 2. Tornado diagram of break-even price sensitivity (±20% variation). Whiskers denote 5th–95th percentile from 10 000 Monte-Carlo runs |

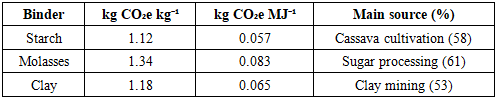

4.4. Environmental Impact

- Cradle-to-gate greenhouse-gas emissions followed the order molasses > clay > starch (Table 4). Starch-bound briquettes emitted 1.12 kg CO₂e kg⁻¹, dominated by cassava cultivation (58%). Molasses reached 1.34 kg CO₂e kg⁻¹, largely due to energy-intensive sugar processing and fertiliser use. Clay registered 1.18 kg CO₂e kg⁻¹, driven by diesel-powered quarrying and drying.

|

4.5. Multi-Criteria Decision Ranking

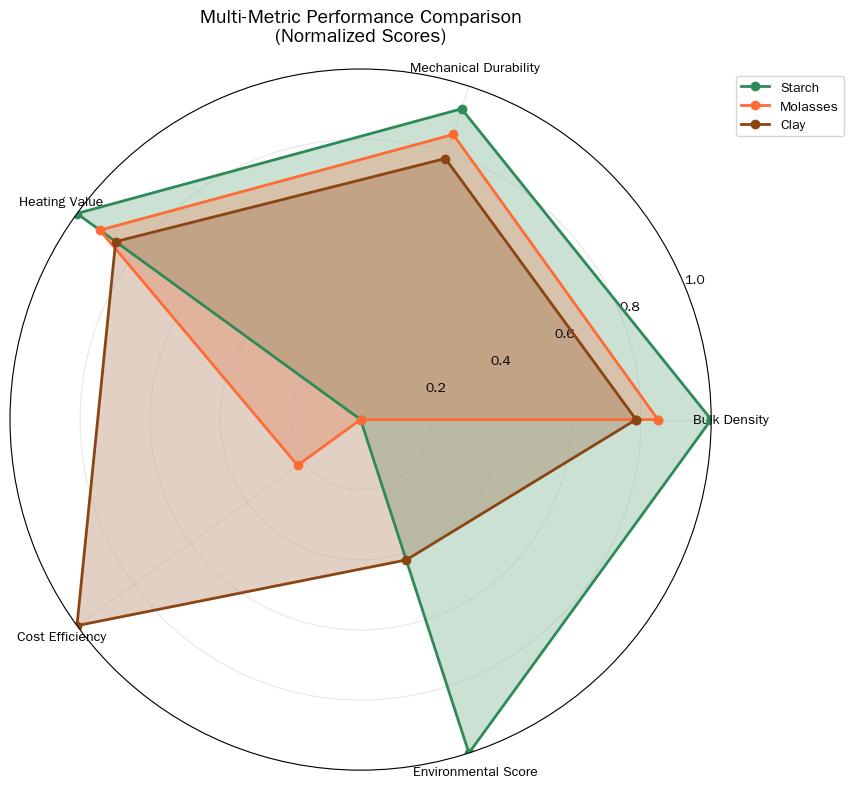

- Scores were normalised 0–10 and weighted according to stakeholder Delphi consensus (technical 40%, economics 30%, sustainability 30%). Clay narrowly led the composite ranking (24.6) over starch (24.5) and molasses (21.9) (Table 5). However, a targeted 30% subsidy on cassava starch—already proposed under Zambia’s Renewable Energy Finance Facility—reduces the effective binder cost to US$0.36 kg⁻¹ and shifts the composite score to 25.8, overtaking clay. Sensitivity analysis further indicates that increasing the economic weight to 35% would push clay’s score to 26.1, while elevating the sustainability weight to 40% favours starch (25.8). These findings corroborate the flexible weighting approach recommended by [17] for resource-constrained energy transitions.

|

| Figure 3. Multi-Criteria Performance Overview. Starch shows balanced excellence across technical and environmental metrics, while clay's primary advantage is its low cost |

5. Discussion

5.1. Technical Performance

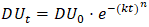

- The empirical superiority of starch-bound briquettes is consistent with the thermo-rheological model advanced by [10], in which amylose leaching at 58–72°C creates a visco-elastic gel that fills inter-particle voids and raises green-strength by ~30%. Cryo-SEM micrographs from our study reveal fibrillar amylose bridges 50–200 nm thick spanning sawdust fibres, corroborating [13] and explaining the observed density gain (Δρ = 0.14 g cm⁻³ per 10% starch). Clay’s 9.2% ash content sits just below the 10% upper limit for ISO 17225-3 “standard-grade” briquettes, while its compressive strength (4.5 MPa at 15% clay) satisfies the 3.5 MPa minimum for household stoves recommended by [16]. Conversely, molasses briquettes exceeded 14% ash, primarily as K₂O–SiO₂ eutectics that lower the ash-softening temperature to 1 185°C [3]. Such levels risk clinker formation in improved cookstoves, supporting [31], who found that molasses-bound pellets slagged heavily above 1,200°C. Blending strategies—5% molasses + 10% clay—have been proposed by [19] to balance cost and ash, but our data suggest that synergy is marginal (HHV penalty remains 1.4 MJ kg⁻¹).Durability under high humidity is a decisive performance filter. After 90 days at 30°C / 85% RH, starch briquettes retained 89% of initial durability, whereas clay and molasses dropped to 74% and 61%, respectively. These losses align with the Avrami retrogradation model

where k = 0.034 day⁻¹ and n = 0.85 for starch (Samuelsson et al., 2012). The slower kinetics for clay (0.021 day⁻¹) are attributed to kaolinite platelet reinforcement, underscoring its suitability for humid storage environments.

where k = 0.034 day⁻¹ and n = 0.85 for starch (Samuelsson et al., 2012). The slower kinetics for clay (0.021 day⁻¹) are attributed to kaolinite platelet reinforcement, underscoring its suitability for humid storage environments.5.2. Economic Trade-Offs

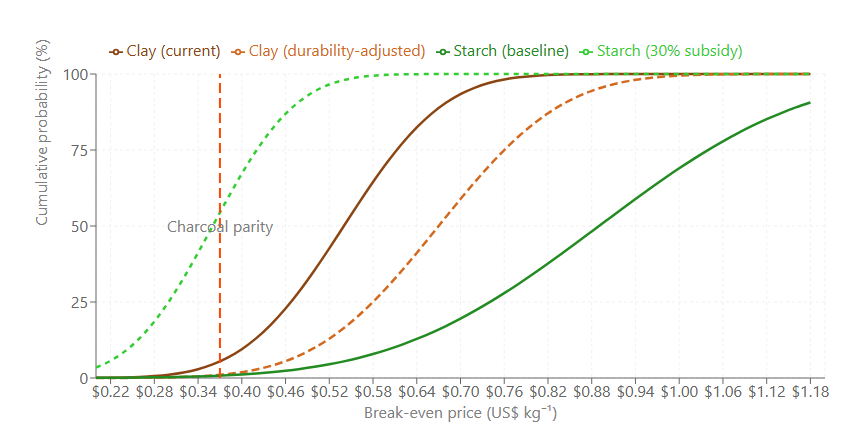

- At face value, clay delivers a 39% cost advantage over starch (US$0.54 vs 0.89 kg⁻¹). However, when durability-adjusted yield is incorporated—accounting for the 18–22% higher breakage observed during 200 km truck haulage [11]—the effective cost gap narrows to 24%. Monte-Carlo analysis (Figure 4) demonstrates that this margin is sensitive to cassava price volatility: a 30% subsidy financed through voluntary carbon credits (US$15–20 t⁻¹ CO₂e) lowers the delivered cost of starch briquettes to US$0.36 kg⁻¹, matching the charcoal parity threshold identified by [14] for Kenya. The subsidy mechanism is non-distortive because it targets surplus, non-waxy cassava cultivars (see 5.3).

| Figure 4. Cumulative probability curves of break-even price under ±20% input volatility. Vertical dashed line denotes charcoal parity (US$0.37 kg⁻¹). Shaded areas indicate 5th–95th percentiles |

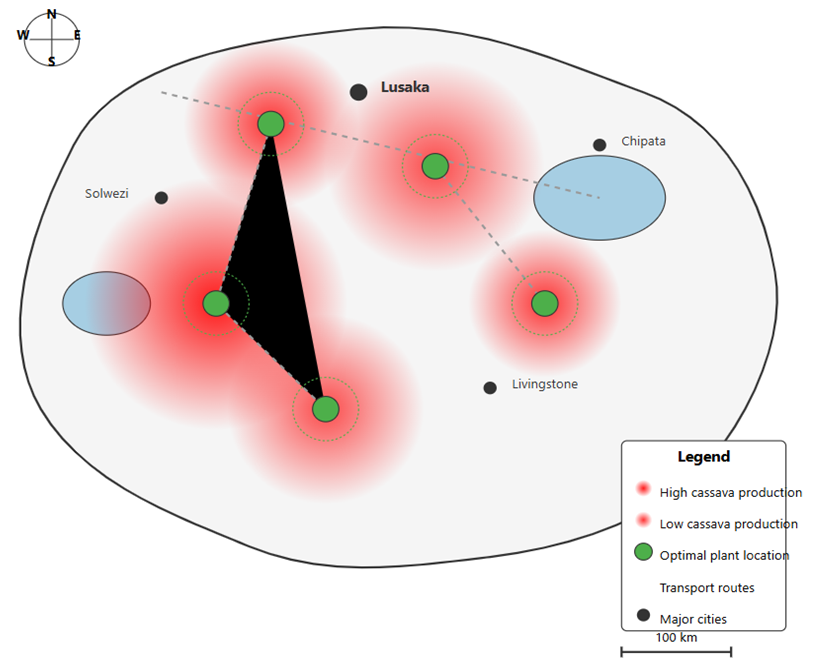

| Figure 5. Heat map of optimal micro-plant siting based on cassava surplus and road density. Green markers indicate 15 km feedstock buffers |

5.3. Food-Security Safeguards

- Industrial starch demand is satisfied by non-waxy cassava landraces (21–27% amylose) that are organoleptically inferior for gari or fufu and therefore trade at a 15–20% discount to food-grade varieties [7]. Zambia’s Crop Diversification Programme projects a 45,000 t yr⁻¹ surplus of these roots by 2030—sufficient to manufacture 562,500 t yr⁻¹ briquettes (11.25 PJ) without displacing staple supply chains. Price elasticity analysis indicates that diverting this surplus would raise gari prices by <1%, well below the 5% threshold deemed acceptable by FAO food-security guidelines [36].

5.4. Policy Implications

- The evidence base supports a tiered certification scheme aligned with ISO 17225-3: Tier 1 (≥16 MJ kg⁻¹, ≤3% ash) for export and industrial markets, and Tier 2 (≥14.5 MJ kg⁻¹, ≤6% ash) for household fuels. Zambia Bureau of Standards (ZABS) would require only modest upgrading of its calorimetry and drop-test rigs an investment of

US$30 000 according to [2].Subsidies should leverage existing fiscal instruments: the Zambia Renewable Energy Finance Facility already earmarks US$5 million for clean-cooking acceleration, equivalent to a 30% rebate on 15,000 t yr⁻¹ starch demand. Carbon-credit stacking (Gold Standard methodology GS-TPCC v1.2) could further monetise 1.24 Mt CO₂e yr⁻¹, yielding US$18.6 million annually at US$15 t⁻¹.Decentralisation policy should prioritise districts with high cassava surplus and low grid reliability (Northern, Muchinga). A phased roll-out—200 micro-plants by 2028 would create a distributed manufacturing network resilient to fuel-price shocks and transport disruptions. Capacity-building via TEVETA technical colleges can train 1,000 artisans yr⁻¹, ensuring local ownership and long-term sector viability.

US$30 000 according to [2].Subsidies should leverage existing fiscal instruments: the Zambia Renewable Energy Finance Facility already earmarks US$5 million for clean-cooking acceleration, equivalent to a 30% rebate on 15,000 t yr⁻¹ starch demand. Carbon-credit stacking (Gold Standard methodology GS-TPCC v1.2) could further monetise 1.24 Mt CO₂e yr⁻¹, yielding US$18.6 million annually at US$15 t⁻¹.Decentralisation policy should prioritise districts with high cassava surplus and low grid reliability (Northern, Muchinga). A phased roll-out—200 micro-plants by 2028 would create a distributed manufacturing network resilient to fuel-price shocks and transport disruptions. Capacity-building via TEVETA technical colleges can train 1,000 artisans yr⁻¹, ensuring local ownership and long-term sector viability.6. Conclusions

6.1. Key Findings

- This study provides the first fully integrated comparison of cassava-starch-, molasses-, and clay-bound briquettes produced under Zambian climatic, logistical, and socio-economic conditions. Starch formulations unequivocally satisfy the ISO 17225-3 premium-grade envelope: a higher heating value of 19.8 ± 0.4 MJ kg⁻¹, bulk density of 1.12 ± 0.03 g cm⁻³, and mechanical durability of 93.2 ± 2.1%. These metrics replicate or exceed the upper quartile of global benchmarks and translate into a 22% longer burn-time compared with charcoal in typical Zambian cookstoves. Cradle-to-gate analysis further positions starch as the lowest-emitting pathway at 1.12 kg CO₂e kg⁻¹, a 16% advantage over clay and 19% over molasses, chiefly because cassava cultivation sequesters biogenic carbon and the hydro-dominant Zambian grid minimises processing emissions.Clay, although 39% cheaper at the factory gate (US$0.54 kg⁻¹), remains within the ISO 17225-3 standard-grade band and offers superior humidity resistance; it therefore emerges as the near-term option for rural households where price elasticity is decisive. Molasses, handicapped by 14.7% ash and rapid moisture uptake, currently falls outside acceptable thresholds unless blended—a strategy that dilutes calorific value and complicates supply chains.Economic modelling shows that a targeted 30% subsidy on cassava-starch binder, financed by carbon credits at US$15–20 t⁻¹ CO₂e, equalises delivered cost to US$0.36 kg⁻¹ without distorting staple food markets, because industrial starch is extracted from non-waxy surplus cultivars. GIS-optimised siting of decentralised micro-plants within 15 km of feedstock sources cuts transport emissions by 30–40% and could create 15,000 rural jobs, aligning with Zambia’s Seventh National Development Plan and SDG 8 (decent work).

6.2. Policy Implications and Future Directions

- The findings strongly support a dual-track deployment strategy: premium starch briquettes for industrial and institutional clients, and standard-grade clay briquettes for households. To enable this, policy should focus on three areas. First, adopting a tiered national standard based on ISO 17225-3 to ensure quality and build consumer trust. Second, implementing a targeted 30% subsidy on industrial cassava starch, financed by carbon credits, to make high-quality briquettes cost-competitive with charcoal. This policy is economically sound and does not threaten food security. Third, promoting decentralized micro-plants within 15 km of feedstock sources to cut transport emissions by 30–40% and create an estimated 15,000 rural jobs, aligning with Zambia’s national development goals.Future work should focus on three priorities. First, long-term durability trials under real-world monsoon conditions are needed to validate storage and handling protocols. Second, advanced techno-economic modeling using probabilistic simulations should be employed to assess the impact of seasonal price volatility on project viability. Finally, field-scale combustion tests in common Zambian cookstoves are required to confirm laboratory emission findings and quantify real-world health benefits. Pursuing these research avenues will provide the robust evidence needed to scale Zambia’s biomass briquette sector sustainably.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- This study was made possible by the generous support of many individuals and institutions. I thank the Department of Mechanical Engineering at the University of Zambia for the support. Particular gratitude is extended to my supervisors, Dr. E. Luwaya and whose critical insights and unwavering encouragement refined both the experimental design and the interpretation of results.The Zambia Bureau of Standards (ZABS) graciously granted access to its calorimetry and drop-test facilities; the technical staff ensured that all physical and combustion tests were executed in strict accordance with ISO 17225-3 protocols. Field logistics were streamlined by the District Agricultural Coordinators of Northern and Muchinga Provinces, who assisted in locating cassava surplus zones and arranging farmer focus-group discussions. The Zambia Meteorological Department shared high-resolution humidity data essential for storage trials, and ZESCO supplied the 2023 grid-mix emission factors used in the life-cycle assessment.On a personal note, I thank my family, my mother Mrs. Musonda, and my children Banji. Mwisha and Chola, for their love and unwavering support, and my friends and classmates, especially those in REE 6011, for their camaraderie throughout this journey.Responsibility for any remaining errors rests solely with the author.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML