-

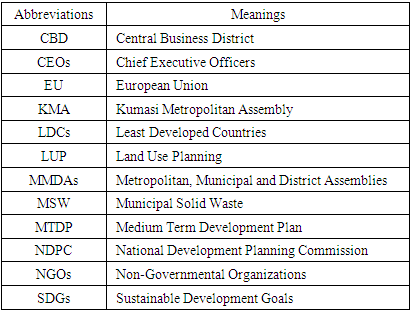

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

World Environment

p-ISSN: 2163-1573 e-ISSN: 2163-1581

2021; 11(1): 26-39

doi:10.5923/j.env.20211101.03

Received: May 16, 2021; Accepted: Jun. 10, 2021; Published: Jun. 30, 2021

Roles and Strategies of the Local Government in Municipal Solid Waste Management in Ghana: Implications for Environmental Sustainability

Shuo Seah, Dominic Addo-Fordwuor

School of Public Administration, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan, China

Correspondence to: Dominic Addo-Fordwuor, School of Public Administration, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan, China.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2021 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

One of the major banes of urban managers in Ghana is the poor management of municipal solid waste (MSW) and this phenomenon inhibits the promotion of environmental sustainability. In Ghana, the local government is a key actor in MSW management at the district level. The study therefore aimed to evaluate the roles and strategies of the local government in MSW management in Ghana using the Kumasi Metropolitan Assembly (KMA) as a case study. To achieve the study objectives, exploratory and qualitative research methods were used in both data collection and analysis. This involved an extensive review of relevant literature, key informant interviews and field observations. Results of the study showed that the local government inter alia, coordinates, facilitates and regulates the activities of MSW management in the Metropolis. The strategies it uses include preparing and implementing medium term development plans, providing waste management infrastructure and land use planning. The authors entreat the local government to among other things adopt an integrated waste management system with suitable policy agenda, social programs and strategic action plans aimed at promoting effective solid waste management. The study concludes that the MSW value chain in the Metropolis should be fully explored by the local government to derive the optimum value from the waste.

Keywords: Roles, Strategies, Local Government, Municipal Solid Waste Management, Ghana, Collaboration, Environmental Sustainability

Cite this paper: Shuo Seah, Dominic Addo-Fordwuor, Roles and Strategies of the Local Government in Municipal Solid Waste Management in Ghana: Implications for Environmental Sustainability, World Environment, Vol. 11 No. 1, 2021, pp. 26-39. doi: 10.5923/j.env.20211101.03.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Municipal solid waste (MSW) management is considered as one of the world’s serious developmental challenges in recent years, owing to the increasing amount of waste generated particularly in urban areas [1–5]. This is especially true for many developing countries in the world [6–10], including Ghana. The increase in per capita generation of solid waste in Africa has not been matched by a proportionate growth and capacity to deal with the increasing production levels [11,12]. In least developed countries (LDCs), there is ample evidence to suggest that the effective management of solid waste in urban areas is becoming an increasingly overwhelming task for local governments owing to challenges such as low collection rates, open dumping, illegal dumping and open burning of waste [5–7,10,13]. For most of the period after 1960, when environmental and resource policy had been dominant public issues, the emphasis of public debates on those policies was at the federal and state levels. However, from the last decades of the century, more and more of the decisions and policies that will define the quality of life for citizens are being made at the local level [14]. Local government is usually responsible for the provision of services which influence people’s behaviour including spatial planning, economic development, infrastructure development, transport, solid waste management and pollution control, education, awareness raising and environmental information [5,8,10,15–20]. Many of the persuasive documents of the 1990s that aimed to bring about a commitment to environmental sustainability acknowledged local government as a relevant actor in the process. For instance, the role of local authorities in environmental protection is enshrined in Chapter 28 of Agenda 21. It states that “local authorities construct, operate and maintain economic, social and environmental infrastructure, oversee planning processes, establish local environmental policies and regulations, and assist in implementing national and sub-national policies” [21]. Also, the EU’s Fifth Environmental Action Plan of 1992 is one of the many documents that placed greater importance on the role of local government, especially on the principle of subsidiarity [22]. There is a local autonomy associated with the local involvement in environmental issues. Local government also has the ability to respond to matters of local concern [23] since it is always in touch with the local citizens. For instance, in Ghana where this study was conducted, the local governments are responsible for inter alia, the management of the natural environment of their various jurisdictions. They are to design consensus–based strategies aimed at promoting the effective and efficient management of MSW in their areas of jurisdiction through an array of measures involving local actors. According to [24], the responsibility of solid waste provision in Ghana has over the years been shifted from the central government to local governments. This makes the local government a key actor in MSW management in Ghana. However, not much is known about the actual roles of the local governments in MSW management and how they execute these roles at the district level. For this reason, the study seeks to evaluate the roles and strategies of the local government in MSW management in Ghana and their implications for environmental sustainability. It will therefore:• Examine the roles of the local government in MSW management at the district level• Identify the strategies used by the local government in MSW management at the district level and• Explore the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and constraints of the local government in MSW management.Identifying the roles and strategies of the local government in MSW management is crucial for policy advice and implementation. Findings of this study will be instructive to policy makers, academics, investors and stakeholders of MSW management during research and planning.

2. Literature Review

2.1. The Role Theory

- Role is a primary concept in sociological theory. It emphasizes the social expectations attached to specific social positions and evaluates the workings of such expectations. Role is defined as “the dynamic aspect of status, contending that every status in society has an attached role and that every role is attached to a status” (Linton, 1936 as cited in [25]). While Linton described status as a collection of rights and duties, subsequent usage regarded status as position and role as the expected set of rights and duties [25]. Meanwhile, some [26,27] have considered roles from an organization centric perspective, where a role’s identity originates from the organization that defines the roles and associations - not from the player itself. In some agent-oriented approaches, the dependency of a role on a group is also apparent [28]. In simple terms, role represents the behavior expected of the occupant of a particular position or status [29]. Role theory talks about the organization of social behavior at both the individual and collective levels and it is considered as one major element in understanding the nexus between the micro-, macro-, and intermediate levels of society [25]. To this end, the role of the local government in MSW management in this study was considered from an organization centric perspective.

2.2. Waste

- The concept of waste is subjective for two main reasons [30,31]. First, a substance is considered as waste when it no longer serves its primary purpose to the user. Thus, one person’s waste output may be used as someone else’s raw material input [30,31]. Moreover, the perception of waste is also influenced by the technological state of the art and by the place where it is generated [30]. According to [7], waste is any material that becomes non-usable after its complete use for a specific purpose. Waste generation is a natural outcome of human life [18]. [32] have also noted that waste generation is an important byproduct of socio-economic activities while [33] asserted that waste is an outcome of inadequate thinking.

2.3. Solid Waste

- In Agenda 21, solid waste is defined to include “all domestic refuse and non-hazardous wastes such as commercial and institutional wastes, street sweepings and construction debris” [21]. In the view of [34], solid waste may include all discarded solid substances originating from household, healthcare, agricultural, commercial, institutional and industrial activities. The term solid waste describes any “garbage, refuse, or sludge from a waste treatment plant, water supply treatment plant, or air pollution control facility and other unwanted substances which include solid, liquid, semisolid, or contained gaseous material generated from industrial, commercial, mining, and agricultural activities” [35]. The foregoing description of solid waste fits clearly in the situation pertaining to many developing countries, where solid waste is barely separated at source, collection, transportation and disposal points [36]. For this reason, sewage, dissolved solids in water and industrial waste are usually considered to be part of MSW in developing countries contrary to how MSW is categorized by some authors and in some other jurisdictions [37].

2.4. Municipal Solid Waste

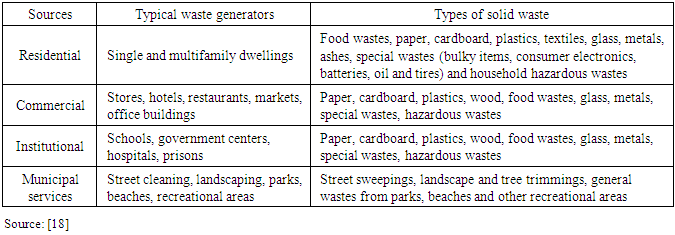

- Depending on their source, solid waste can be grouped into different types: “household waste is generally classified as municipal waste; industrial waste as hazardous waste and biomedical waste or hospital waste as infectious waste” [35]. [8] were of the view that MSW generally comprises household refuse, nonhazardous solid waste generated from industries, commercial and institutional settings which includes hospitals, and wastes from the market and yard together with street sweepings. There are two major classes of MSW which are organic and inorganic. The organic MSW can also be categorized into three groups as putrescible, fermentable and non-fermentable. Products such as foodstuff that decompose fast are good examples of putrescible wastes. Wastes that decompose rapidly, but without the fetid accompaniments of putrefaction are the fermentable wastes while non-fermentable wastes usually resist decomposition and for that matter degrade very slowly. Inorganic solid waste comprises substances such as plastics, metals and other non-biodegradable materials [34]. A summary of some sources and types of MSW is depicted in Table 1.

|

2.5. Municipal Solid Waste Management

- As a means to address contemporary environmental, technical and economic challenges, waste management has been developing operationally and technologically during the last few decades. Conventionally, waste management is deemed necessary when the pressure to handle the problem exceeds the convenience of disposal. The urgency to manage the problem emerges when people are affected by the impacts of the waste disposal [33]. [38] succinctly captured the definition of solid waste management as a discipline associated with the control of generation, storage, collection, transfer and transport, processing and disposal of solid wastes. They further categorized the direct activities of solid waste management into six functional elements: (1) waste generation and characterization, (2) on-site storage and handling, (3) collection, (4) transfer and transport, (5) separation processing, treatment and resource recovery, and (6) final disposal. To achieve optimal service delivery, these functional elements must be well planned and managed. In this 21st century, waste management is an important activity which helps in sustaining our society, particularly, in urban areas [4]. Safeguarding proper sanitation and solid waste management sits alongside the provision of potable water, shelter, food, energy, transport and communications as vital to society and to the economy as a whole [4]. [39] discounted the need for establishing technical and costly solutions to achieve sustainable MSW management. Instead they recommended appropriate waste separation which considers the lifestyle of residents as the key strategy needed. In a similar line of argument, [17] noted the frequent misconception people have about technology as being the solution to the issue of unmanaged and increasing waste. Thus, technology is one of several other factors to consider in solid waste management and should not be regarded as a panacea to the issue [17].

2.6. Municipal Solid Waste Management in the Context of Environmental Sustainability

- [8] noted the significance and consequence of waste management on public health and well-being, the quality and sustainability of the urban environment and the efficiency and productivity of the urban economy. In view of this, global efforts are currently geared towards the reorientation of solid waste management systems toward sustainability [18]. [40] have posited that waste management is now considered as part of the general global concern for sustainability and transcends national frontiers in terms of problems and possible solutions. Waste management therefore, is seen as a central issue in environmental sustainability. The major hindrance domestic waste poses to the realization of environmental sustainability in the 21st century has been underscored in Agenda 21 [21]. This action plan has been influential in solid waste management [41]. Solid waste management affects each of the three sustainability domains of ecology, economy and society. Areas such as living conditions, sanitation, public health, marine and terrestrial ecosystems, access to decent jobs, as well as the sustainable use of natural resources are affected by MSW [42]. The attention paid to the challenge of MSW management as a cross-cutting issue has resulted in its integration into 12 out of the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGS) [42]. One of the most essential elements for promoting sustainable development in urban areas is MSW management [43]. [15] has also emphasized the importance of assessing solid waste management services by not only considering the benchmarks of cost efficiency and service effectiveness, but also by considering issues such as equality (in access), broad coverage, affordability and environmental concerns. These benchmarks are incorporated into the broader concept of ‘sustainable development’ [15]. Protecting public health by extending waste collection to everyone, and protecting both the local and global environment by eliminating uncontrolled disposal and open burning of solid waste have been identified as two short-term priorities among the waste-related SDGs [4,42].

2.7. Previous Studies on Municipal Solid Waste Management in Ghana

- A plethora of literature is extant about solid waste management in various urban areas in Ghana. For example, various studies conducted in Accra [12,44], Kumasi [45], Berekum [46,47], Wa [48], Bawku [49] and Sekondi-Takoradi [50] have all brought to the fore the poor solid waste delivery services in urban parts of Ghana. In fact, MSW management is considered as the role of city authorities in Ghana and many African countries with urbanites always looking up to the authorities to save them from the problem [11]. This assertion is in consonance with the findings of the study by [49] in the Bawku Municipality in Ghana, where respondents stated that the issue of waste management is the exclusive responsibility of the local government. Proper solid waste management in Ghana has become a critical environmental issue for the local government also referred to as Metropolitan, Municipal and District Assemblies (MMDAs) and regardless of the efforts of authorities to remediate the situation, it still remains a great hurdle to surmount [1,46].

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Study Area

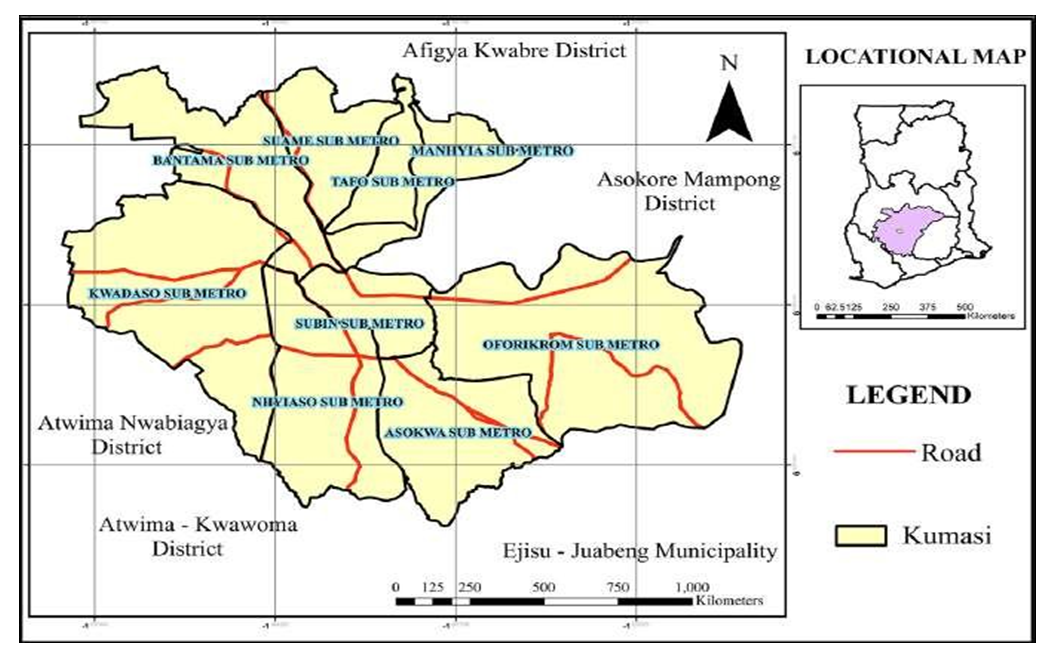

- The Kumasi Metropolitan Assembly (KMA) was used as the case study for the research (Refer to Fig. 1). KMA is one of the forty-three (43) districts in the Ashanti Region of Ghana. According to the 2010 Population and Housing Census, the population of Kumasi Metropolis in 2010 was 1,730,249 and represented 36.2 percent of the total population of Ashanti Region at the time [51]. It has a growth rate of 5.4 which is far higher than the regional and national growth rates of 2.7 and 2.5 respectively [52]. Currently, Kumasi is the second most populous city in the country, after the national capital, Accra [51]. Given its rapid population growth and urbanization, the Metropolis accommodates a substantial fraction of the entire population of the Ashanti Region. This has facilitated the spread of development to the adjoining districts [51]. Located between Latitude 6.35° N and 6.40° S and Longitude 1.30° W and 1.35° E, Kumasi has a surface area of approximately 214.3 square kilometers which is about 0.9 percent of the region’s land area. Owing to the beautiful layout and greenery of the City, Kumasi was accorded the accolade of being the “Garden City of West Africa”. Unfortunately, the city has lost a substantial portion of its vegetative cover to physical construction due to urbanization [51]. KMA was selected for the study because of its highly urbanized nature and its relatively high solid waste generation rate.

| Figure 1. Map Showing the Study Area (Source: [51]) |

3.2. Methodological Approach

- The qualitative exploratory case study approach was mainly used for this study. This approach involved three main steps. The first step was a desk study involving a review of official reports, scholarly literature and archival records relating to MSW management in Ghana, and Kumasi in particular. The roles and strategies used by the local government in the process were reviewed. The next step involved in-depth interviews with personnel in charge of MSW management at the Kumasi Metropolitan Assembly, after reassurance about confidentiality. Interviews conducted with the personnel of the Assembly sought information on waste collection up to disposal followed by the involvement of all stakeholders during the planning and decision-making process. Using purposive sampling, we solicited 10 respondents’ appreciation of the roles and strategies of the local government in MSW management. The semi-structured interviews sought responses on topics such as solid waste composition and the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and challenges of the local government in MSW management. The last step involved site visits to dumpsites, transfer stations and the landfill site in the Kumasi Metropolis to get firsthand information of activities at these sites. The data was analyzed qualitatively through an in-depth evaluation of the various topics under consideration.

4. Findings and Discussions

4.1. Solid Waste Generation and Composition

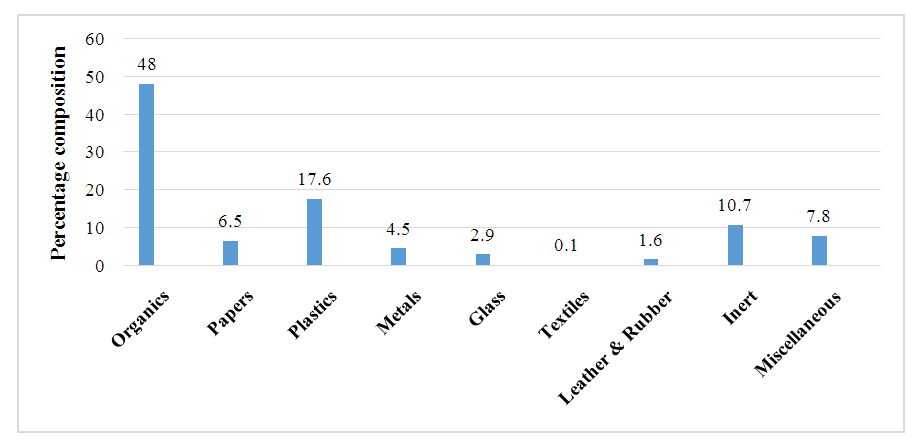

- In 2011, an average of 1,500 metric tons of solid waste were generated daily in Kumasi [53]. The rate increased to an estimated value of 1,689 metric tons per day in 2015 [54]. In that same year, it was estimated that an average rate of 0.75 kg/capita/day of waste was generated in the Metropolis. It is worth noting that the rate of generation of solid waste across the high class income, middle class income and low class income areas of the Metropolis varied markedly and were recorded as 0.63 kg/capita/day, 0.73 kg/capita/day and 0.86 kg/capita/day respectively [54]. [32] have confirmed this trend by arguing that there may be variations in the generation and characteristics of MSW at the level of country, state, city as well as within different areas of the same city. Statistics from the Metropolitan authority show that currently, the city generates over 2,000 metric tons of waste daily [55]. High growth rate, changes in consumption pattern and economic growth have been significant contributory factors to the high rate of solid waste generation in the city. This finding validates earlier studies by some scholars [17,56,57]. The sources of solid wastes in Kumasi include households, shops, restaurants, markets, offices, hospitals, schools, factories, etc. [53]. [54] outlined the composition of MSW generated in Kumasi which consists of a high percentage of organics (48%) (see Fig. 2) and this is confirmed by the findings of [32] that the composition of MSW in low income countries is characterized by high percentage of organic matter (40–85%).

| Figure 2. Composition of Municipal Solid Waste in Kumasi (Source: Authors’ construct with data from [54]) |

4.2. Solid Waste Segregation and Storage

- In the Kumasi Metropolis, waste segregation at source is seldom done. The practice however is carried out in various higher educational institutions, mainly for research purposes. Most people use plastic containers while others use metallic containers and polythene bags for storing the generated waste temporarily. The sizes of containers used differ and are generally influenced by the size of the household, institution or market. Medium- and large-sized containers are mainly used in educational institutions and commercial locations such as markets and the central business district (CBD).

4.3. Solid Waste Collection

- Waste collection is an integral functional component of the waste management system. The lack of an effective solid waste collection system has the tendency to inhibit the waste management flow and contributes to waste generators adopting illegal and unwanted practices such as dumping at unapproved locations and backyard burning of wastes [58]. House-to-house collection (about 20%) and communal collection points (about 80%) are considered to be the major forms of waste collection in the Metropolis [53]. Through a competitive tendering process, the KMA has outsourced the collection and disposal of waste generated in the Metropolis to five private companies. These companies are the Kumasi Waste Management Limited, Asadu Royal Waste, V-Max and Sakkem and Antoco [51,53]. Each of the companies is assigned a particular zone within the Metropolis. Households and institutions that subscribe to the services of the private companies pay a monthly fee for the bins they have been provided with and the collection of the solid waste they generate. House-to-house waste collection is becoming a common practice in many high income residential areas in the Metropolis since communal waste disposal sites are generally lacking in those areas. Two main methods of house-to-house collection are commonly practiced in the Metropolis. Under the first method, households, institutions and markets position their generated waste at vantage points on their premises or bring them in front of their premises pending collection by the waste company. The collection staff enters the premises, takes out the waste container, empties the container into the collection vehicle and returns it to its position. This method is mainly practiced in areas where roads are in good condition and so are easily accessible by the trucks. The second method involves mobile waste collection trucks which travel a specified route at regular intervals (usually a three-day interval), and stop at designated locations where a siren is sounded. Upon hearing the siren, the householders carry the refuse to the trucks and hand it over to the staff who empty the containers and hand them over to the householders. This method is practiced in areas where most of the roads are inaccessible by the trucks due to the deplorable state of the roads. The waste collected in the truck is then carted for direct disposal at the landfill site or disposed of at the nearest transfer station for onward disposal at the landfill site. The waste collection system by the service providers is irregular and often characterized by non-compliance with weekly schedules on the part of service providers and default of payment by householders. Households in the middle income residential areas in the Metropolis usually have access to house-to house waste services or communal containers at designated points. Households that are not able to afford the services of the private waste companies opt for the services of informal waste collectors. These informal waste collectors use handcarts and tricycles for waste collection from individual houses at specific times in the morning. A relatively less amount of money is paid by the dumper after the waste has been collected. The low income residential areas in the Metropolis usually have communal dump sites or central containers placed at designated points. Householders carry their wastes and dispose them of at the dump sites or communal containers. Refuse collection trucks visit the communal containers at frequent intervals, usually once a day or every other day, to remove accumulated waste for final disposal at the landfill site. House-to-house waste collection is not a common practice in these areas because a good number of households do not have the ability to pay for the services.

4.4. Solid Waste Disposal

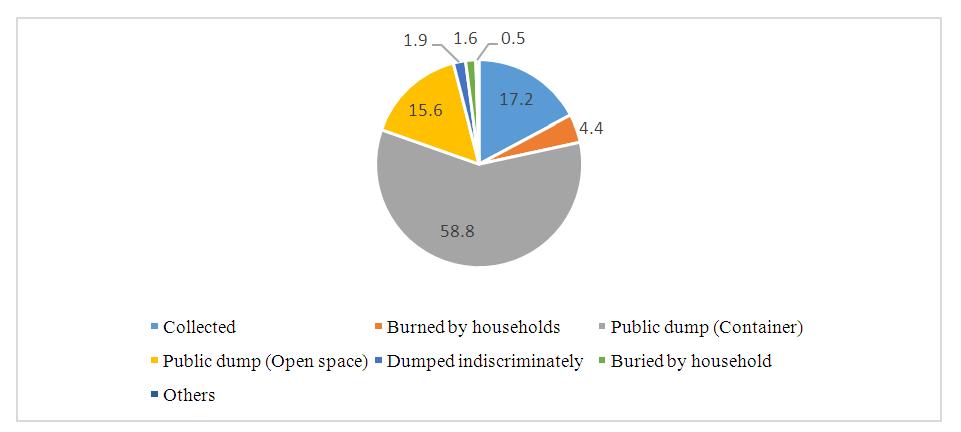

- Out of the numerous solid waste management techniques available, waste disposal is the most preferred option in Kumasi, even though it is the least sustainable and most unfavorable technique in the waste management hierarchy. The two main categories of waste disposal are sanitary landfilling and open dumping [13]. Sanitary landfilling refers to the disposition of waste in an engineered disposal site [59] while open dumping denotes the indiscriminate discarding of waste in disposal sites without regards to environmental protection and safety of the people [17,59]. Between sanitary landfilling and open dumping, the latter is the less preferred option but it is the commonly practiced in Kumasi, likewise many other cities in developing countries [13]. The 2010 Population and Housing Census report indicated that out of the total amount of waste generated in Kumasi, 17.2% is collected, 4.4% is burned by households, 58.8% is disposed of at public dump (container) and 15.6% is disposed of at public dump (open space). The report further indicated that 1.9% of the waste is dumped indiscriminately, 1.6% is buried by households and the remaining 0.5% is disposed of by other means (Refer to Fig. 3) [51].

| Figure 3. Waste Disposal Methods in Kumasi (Source: Authors’ Construct with data from [51]) |

4.5. Roles of the Local Government in Municipal Solid Waste Management in the Legal Context

- In Ghana, the local government is the principal authority entrusted with the functions of day to day administration, planning, budgeting and implementation of the programmes and projects aimed at facilitating development in the Metropolis. It can therefore be inferred that these functions of the local government require it to among other things coordinate, facilitate and regulate the activities of MSW management in the Metropolis. [60] noted that, provision of solid waste management services is inadequate in many municipalities in the developing world, although in most countries the ultimate responsibility of solid waste management is a legally prescribed municipal role. To this end, local governments need to step forward to assume a greater role in leadership in the field of solid waste management [23], as the legal framework which constituted the local government situates it as the main body to regulate environmental issues in the Metropolis. Legal mandates are legal provisions that offer an enabling environment for the local government to be involved in environmental management. [23] asserted that when local governments understand the boundaries within which they can regulate environmental matters as they are enjoined by their legal mandate, then unnecessary and wasteful pre-emptive challenges can be avoided. Responsibility for waste management by local governments is usually stated in bylaws and regulations and may be derived, more generally, from policy goals concerning environmental health and protection [8]. In Ghana, the local government is an institution authorized by law to manage the environment at the district level. The Local Government Act of Ghana (Act 462) is the source of this authority. Section 10 (3) of the Act specifies one of the roles of the local government as being responsible for the development, improvement and management of human settlements and the environment in the district. This positions the local government to promote the management of all aspects of the environment including MSW management in their areas of jurisdiction. The effective management of the environment is very crucial in ensuring the health of the people and protection of the environment at the local level. The Act also stipulates that local governments are to initiate programs for the development of basic infrastructure and provide municipal works and services in the district. The infrastructure includes engineered landfill sites for the treatment of solid waste after disposal, transfer stations for the solid waste and good roads to cart the solid waste from the transfer stations to the landfill sites by trucks. Municipal works and services include among other things the effective MSW management in the Metropolis. As a matter of principle, the authority to enforce bylaws and regulations, and to mobilize the resources needed for solid waste management is conferred on local governments by higher authorities [8].Act 462 also makes provision for the local government to mobilize financial resources to support its budget for the activities to promote development in the district. Even though the Act is very definite about the local government having the authority to develop, improve and manage the environment in the district, it is silent about the strategies to achieve this. The Act also authorizes the local government to pursue programs and projects which will inure to the benefit of the district, but does not prioritize these programs and projects. MSW management therefore competes for priority with other equally important activities on the list of the local government to be performed to bring about development in the Metropolis. The actual role of the local government in MSW management is also not well defined in the Act and this does not facilitate effective and efficient MSW management by the local government in the district. The local government has the authority to generate funds internally to support its activities in MSW management in the Metropolis. The activities comprise raising awareness in the Metropolis about the need to avoid and reduce, reuse and recover waste whenever possible as prescribed by the waste management hierarchy [9,18,56]. A provision in the Act enjoins the local government to cooperate with appropriate national and local security agencies for the maintenance of public safety in the district. Public safety includes a healthy population and a sound physical environment. One way of achieving this is to promote good sanitation by way of effective management of MSW in the Metropolis. Thus, the local government is responsible for public health and environmental protection in the Metropolis. This role seems too enormous to be undertaken solely by the local government. Accordingly, the involvement of other actors by the local government in MSW management was identified as an important factor which complements the local government’s legal role in MSW management. If well managed, waste can be integrated into the environment for mutual benefit [61]. Meanwhile, the need to consider both the socioeconomic and environmental impacts of waste during solid waste management planning has been recently emphasized [62]. In line with this, the local government should build infrastructure and initiate projects and activities aimed at exploring the economic potentials of waste as well as protecting the environment. These will attract other actors to be involved in the MSW management activities of the local government.

4.6. Strategies of the Local Government in Municipal Solid Waste Management

- At the core of any organization is their strategy to function. Managers and chief executive officers (CEOs) are faced with the arduous task of successfully directing their organizations through varying situations. In most organizations the formulation of an appropriate strategy, based on a set of objectives, is used as a means to direct the organization to achieve a level of value or return while considering the threats and opportunities existing in their current environment [63]. The primary connotation of strategy was taken by Chandler, to focus on a logical sequence of goal-setting and resource allocation within firms. According to him, “strategy is the determination of the basic long-term goals of an enterprise, and the adoption of courses of action and the allocation of resources necessary for carrying out these goals” (Chandler 1962 in [64]). Consistent with this definition is the one propounded by Johnson and Scholes, which states that “strategy is the direction of an organization, which matches its resources to its environment in order to meet stakeholders’ expectations” (Johnson and Scholes 1993 in [64]). To fulfil the mandate given them by the Local Government Act (Act 462) to improve and manage the environment in their areas of jurisdiction, local governments usually devise a number of interventions. This is because according to Peters (1984) as cited in [65], in solid waste management and processes, the operation strategy is a very crucial tool. From the review of literature, key informant interviews and site visits conducted, the following strategies were identified to be used by the local government in MSW management in the Metropolis.

4.6.1. Preparation and Implementation of Medium Term Development Plan

- One of the major strategies of local governments in MSW management in Ghana is the preparation and implementation of a comprehensive development plan, referred to as the district medium term development plan in Ghana. The plan which covers all sectors of the metropolitan economy and development comprises the plans of most of the departments and agencies under the local government. The goal of the medium term development plan (MTDP) is to achieve the status of decentralized public administrative system with the capacity to support the initiation and implementation of policies and plans to accelerate development to improve the quality of life of the citizenry. The MTDP is prepared and implemented for a maximum of five years and contains all the policies, development goals and objectives likewise the programs, projects and activities to be implemented during the entire planning period. The preparation and implementation of the MTDP is mandatory by the central government of all district assemblies in the country. The National Development Planning Commission (NDPC) supervises and issues guidelines for the preparations of these plans. The current MTDP of the KMA was prepared for the 2018-2021 planning period in line with the current national development framework fully aligned with the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Though the plan is not exclusive for MSW management, issues and activities related to environmental protection and solid waste management are captured and incorporated in the plan. The plan contains the policies, goals, objectives, programs, projects and activities on solid waste management for the planning period in question.

4.6.2. Provision of Waste Management Infrastructure

- Even though MSW infrastructure plays a significant role in the implementation of the United Nations SDGs, till now, quantitative analysis of the advancement in waste management infrastructure delivery worldwide has been absent [66]. The local government studied recognizes the relevance of infrastructure in MSW management. Consequently, the provision of infrastructure has been included in various program based budget estimates of the Assembly. For example, the Assembly has effected, facilitated and supported the construction and provision of various infrastructural facilities in the Metropolis [67]. Among these facilities are waste transfer stations and landfill sites. It also shapes and maintains roads within the Metropolis to facilitate the movement of waste trucks. This strategy of the Assembly originates from the Local Government Act 462 of Ghana, section 10 (3) which among other functions enjoins the Assembly to ensure the overall development of the district and initiate programmes for the development of basic infrastructure. The aim of this is to enhance the operation and performance of MSW management within the Metropolis and adjoining districts.

4.6.3. Land Use Planning

- Land use planning (LUP) is considered as a decision-making process that “facilitates the allocation of land to the uses that provide the greatest sustainable benefits” [21]. LUP controls the use of land in specific areas. It aims at achieving a balance between the needs of people inhabiting on a piece of land and the physical environment. It specifies which part of an area can be used for residential, commercial, industrial, restricted and other purposes. LUP is normally achieved through zoning and according to [68], zoning directs the design and development of neighborhoods and cities. In Ghana, land use planning is a responsibility of all local governments. They are expected to prepare spatial plans, approve and issue permits for any physical constructional activities within their areas of jurisdiction. This responsibility also serves as a tool for MSW management by the local government in the Metropolis. Through LUP, the Assembly has designated specific areas within the Metropolis for solid waste disposal. The encroachment of one land use by another is checked by effective land use planning. The Physical Planning Department of the Assembly prepares land use plans and layouts for the various suburbs of the Metropolis. The exercise is normally performed in conjunction with the custodians of the land and traditional leaders of the suburbs.

4.6.4. Provision of Waste Bins

- The KMA considers the provision of domestic waste bins and communal refuse containers as a priority in the management of MSW in the Metropolis. In this regard, the Assembly has been providing these facilities to communities and households. For instance, the Assembly distributed 1,000 domestic waste bins in 2016 and 1,500 in 2017. It also targeted to distribute 1,000 domestic waste bins in 2018. The Assembly again provided 20 communal refuse containers in 2016, 20 in 2017 and targeted to provide 10 in 2018 [67].

4.6.5. Sensitization Campaigns

- The Assembly organizes regular visits to selected schools and radio stations in the Metropolis aimed at engaging students and the public as a whole on proper waste management practices. These visits strengthen the participation of stakeholders in solid waste management and influence changes of behavior patterns that amount to improper solid waste management.

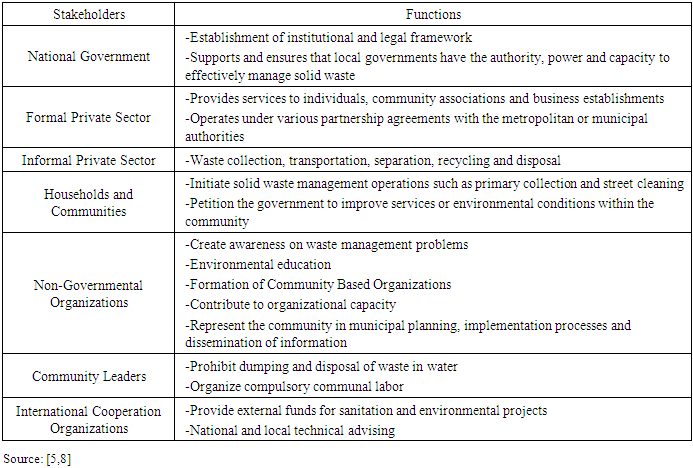

4.6.6. Collaboration with Other Stakeholders

- Although, the final responsibility of waste management in urban areas rests with local governments, it is usually beneficial to execute service provision tasks in partnership with private enterprises (privatization) and/or with the users of services (participation) [8]. To ensure sustainability in solid waste management in urban areas, there must be collaboration between the government, private sector and residents [69]. [16] underscored that the environmental problems of urban areas can be addressed largely by the collaboration of several actors/stakeholders (see Table 2) because various stakeholders have roles to play to support priority actions. Stakeholders comprise people and organizations having an interest in good waste management and involving in practices that make it possible [16]. The KMA recognizes the identification of stakeholders and their interests as very crucial in coordinating their involvement and participation in different waste management activities. It collaborates with these stakeholders at various stages of the waste management process to achieve the desired effects in the Metropolis. Some of the identified stakeholders include the public, households, private sector, enterprises, media, Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs), politicians and research institutions. These stakeholders generate waste, provide waste management services or function as organizations involved in certain aspects of waste management in the Metropolis.

|

4.7. Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities and Constraints of the Local Government in Municipal Solid Waste Management

4.7.1. Strengths

- The KMA is endowed with numerous strengths that allow it to play its roles in MSW management in the Metropolis. Majority of the roles it performs are enshrined and supported by waste management policies and the legal framework that established the local government. The local government therefore obtains legitimacy and legality to perform its MSW management roles from these policies and framework. There are departments, committees and sub-committees at the Assembly that are responsible for carrying out specific roles of MSW management in the Metropolis. There is a strong inter-relationship between these departments which facilitates their easy execution of MSW management roles in the Metropolis.

4.7.2. Weaknesses

- There are some weaknesses within the local government system that hamper its ability to perform its role in MSW management satisfactorily. Among them are understaffing, poor logistics and resources and insufficient funds to finance the MSW management activities of the local government. Lack of technical know-how by the Assembly in the implementation of solid waste management technologies such as composting and anaerobic decomposition results in bulk landfilling instead of diverting the wastes towards sustainable technologies. Other weaknesses include the lack of political will to implement certain solid waste management policies and failure to adhere to land use plans resulting in the conversion of areas earmarked for solid waste disposal and treatment into other land uses.

4.7.3. Opportunities

- There are a lot of extant opportunities that can be utilized by the local government in its solid waste management activities in the Metropolis. Among them are the high putrescible organic fraction of the waste generated in the Metropolis [54] and the availability of a waste treatment facility in the Greater Kumasi Metropolitan Area. [61] opined that the primary objective of any waste management practice in Ghana should be focused on exploring the economic potentials of waste as well as protecting the environment. Given the composition and quantity of MSW generated daily in the Metropolis, it can be converted into valuable useable form to enhance sustainable development of the country [61]. There is also the availability of many media outlets in the Metropolis that can raise the awareness of the public on sound waste management practices. The presence of security agencies in the Metropolis to enforce compliance of the public with waste management regulations is also significant. There also exist research institutions in the Metropolis on which the local government can rely for research into proper MSW management practices. Finally, the local government receives support from the central government and foreign and local organizations to complement its efforts in MSW management.

4.7.4. Constraints

- A host of constraints impede the effective performance of the local government in MSW management. One primary constraint identified is the lack of appropriate infrastructure such as suitable road network for effective waste collection within the Metropolis. A similar finding has been reported by [13] in his study on solid waste management in least developed countries. The bad nature of roads within some parts of the Metropolis substantially affect the collection and transport of waste. Aside from poor road network, insufficient sanitary landfill sites in the Metropolis also negatively affects MSW management by the local government. There is only one engineered sanitary landfill site which serves the entire Metropolis and some adjoining districts. This has the potential to shorten the life span of the facility. Also failure of households to source separate the waste they generate is a major constraint as it disrupts attempts to pretreat the waste prior to landfilling. Another constraint is the lack of awareness on the adverse health and environmental impacts of poor waste management practices on the part of the public. Also, a greater part of the budget of the local government is financed by the central government and given the incessant dwindling of funds at the national level coupled with other competing responsibilities, the central government apparently may not be able to fund all activities of the local government especially with regard to MSW management.

5. Conclusions

- To enhance the effectiveness and efficiency of the local government in MSW management, [12] have advocated the proper education of the public and the provision of more communal trash bins by the local government. [61] have also suggested that the local government should consider solid waste disposal as the last resort but not the prime option in its waste management practices. In this regard, the local government should make frantic efforts to promote the more sustainable practice of “3R” (Reduce, Reuse and Recycle) throughout the Metropolis. Achieving waste minimization is pragmatic through promoting the concept of “3R”. Reduce emphasizes any attempt at points of production and consumption aimed at reducing the quantity of waste generated. Reuse means the use of substances repeatedly, which includes protracted use of repaired good or their parts. Recycle points out to the conversion of waste to resources, such as material recycling and recycling by energy resources. Emphasis therefore should be placed on focusing primarily on reducing, reusing and then recycling, while practicing proper disposal. Regardless of the level of waste minimization achieved, waste production in the Metropolis will still be inevitable and so proper solid waste disposal is always essential [70]. Even though there exists a collaboration between the local government and some private waste contractors, [47] in their study on decentralization and solid waste management in urbanizing Ghana, suggested a deeper involvement of the private sector and the people by the local government in MSW management. They recommended the restructuring of institutional arrangements to ensure user involvement and enforcement of legislation as a means of improving MSW management in the Metropolis. [71] have also opined that the local government should adopt an integrated waste management system with suitable policy agenda, social programs and strategic action plans aimed at promoting environmental governance and solid waste management. The study has identified MSW management as an important aspect of environmental sustainability in the city of Kumasi and the role of the local government in the process. Undoubtedly, Ghana continues to experience rapid population and urban growth which bring in their wake generation of large tons of MSW daily. The realization of environmental sustainability in the country is largely dependent on sound solid waste management practice and the local government plays a significant role in this endeavor. In view of the findings that the local government studied has insufficient capacity with respect to finance, technical know-how, expertise and logistics, there is the need to address these concerns. It should collaborate with other stakeholders of MSW management so as to share the financial burden. Aside from the financial gains, the local government stands to benefit from the collaboration by way of capacity building of staff, a high level of compliance with solid waste management regulations by the public, among others. The conventional approach of MSW management by the local government as a reaction to the presence of something that needs to be discarded should be reconsidered because it does not promote environmental sustainability in the Metropolis. The local government should adopt an approach of MSW management which will control the processes that generate waste and encourage households to source separate their waste. MSW presents both challenges and opportunities. Therefore, the MSW value chain in the Metropolis should be fully explored by the local government to derive the optimum value from the waste. This will go a long way in promoting environmental sustainability in the Metropolis.

Appendix A

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- This paper is supported by the China Social Science Foundation, Project Number 13cgl117.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML