-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

World Environment

p-ISSN: 2163-1573 e-ISSN: 2163-1581

2016; 6(2): 25-33

doi:10.5923/j.env.20160602.01

The Implication of Land Grabbing on Pastoral Economy in Sudan

Yasin Elhadary, Hillo Abdelatti

Faculty of Geographical and Environmental Science, University of Khartoum, Sudan

Correspondence to: Yasin Elhadary, Faculty of Geographical and Environmental Science, University of Khartoum, Sudan.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2016 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

The unprecedented increase in the world population coupled with the great demand for food have encouraged several investors to acquire land and water in some developing countries, Sudan is not an exception. This current phenomenon often referred to as “land grabbing” as it always violates the right of local land users and affects the environment. This paper aims to highlight the process by which local and foreign investors acquire communal lands in Sudan and to underline its implication on pastoral livelihood. The paper is mainly based on desk review and deep analysis of some recent documents. The paper has come out with the fact that under the pretext of development and food security, huge communal lands were taken from local producers and leased “soled” to the investors (grabbers). To facilitate land grabbing, the government of Sudan has frequently been embarked on amending land tenure system several times. The Unregistered Land Act of 1971, Ministerial Act of 1996 and the Investment Act of 2013, have paved the way for more land grabbing in Sudan. These acts ignored completely the historical right of the local communities over land resources. Lacks of transparency, unfair compensation and limited or absent consultation of the local communities are some characteristics shaping land grabbing in Sudan. Land for local producers is the main asset and a source of everything (livelihood) thus, denying such right means lacking everything. This explains why food insecurity, spread of poverty, disputes and conflict are now widely dominated most of pastoral areas. The paper aims to contribute to the ongoing debate on land grabbing and open windows for more research in such hot issue. It provides planners with some ideas that might help in formulating sound policy regarding land acquisition. Like any African country, the government of Sudan has to find rational way to make the investment a win win deal if it is really looking for food security, social peace and sustainable development.

Keywords: Land grabbing, Land tenure, Pastoral economy, Land policy, Sudan

Cite this paper: Yasin Elhadary, Hillo Abdelatti, The Implication of Land Grabbing on Pastoral Economy in Sudan, World Environment, Vol. 6 No. 2, 2016, pp. 25-33. doi: 10.5923/j.env.20160602.01.

1. Introduction

- Mush research has been written about the foreign investment in agricultural land, particularly in Africa. This is not a new phenomenon as it has been documented since the colonial period. According to Mann and Smaller (2010) large foreign-owned plantations have long existed in parts of Africa, Asia and Latin America during the colonial era. Less attention has been paid to such investment due to the small scale, nature and political arena at that time. In the last two decades the acquisition of large-scale land by both domestic and foreign investors has increasingly been the focus of laymen, public, researchers, civil society as well as a source of global concern (Antonelli et al., 2015). This current anxiety is due to the urgent need for agricultural lands and water to secure food worldwide particularly after the 2008crisis and recent global climatic changes. In recent years, the term “land grabbing” is widely used instead of “investment or land acquisition”. Owing to the fact that most if not all the investment in developing countries lacks transparency, democratic decision, respecting human rights (Elhadary and Obeng-Odoom, 2012), lack of consultation, giving less attention to the social cost and environmental impacts and always comes at the expense of land “belong” to local communities (Rullia et al., 2013). This led to define land grabbing as the purchase or lease of vast tracts of land by wealthier, food-insecure nations and private investors from mostly poor developing countries in order to produce crops for export (Daniel and Mittal, 2009). In addition to foreign investors, land may also be grabbed by governments or its affiliations. This is represented in taking the land from native citizens in the name of national interest and refusing to pay fair compensation promptly (Elhadary and Obeng-Odoom, 2012). In the context of this paper, land grabbing refers to the transfer of the communal land to be used or owned by both national and international investors without securing livelihood or providing fair compensation to the local producers. Due to the secret nature and lack of transparency in the process of land grabbing, having accurate and up to date data is far dreaming. Therefore, most of the data regarding rate, deals and size are collected through media or from international organizations. Despite this limitation, available literature has shown that this phenomenon has been growing over during the last years (Cotula, 2013; Nolte, 2014) and the number of land-related deals has dramatically increased since 2005, reaching a peak in 2009 (Rullia et al., 2013). Since 2008, around 180 deals have been recorded, while reports of new deals continue to surface (Daniel and Mittal, 2009). The International Land Coalition (ILC) reports that between 2000 and 2011 large-scale plots of land acquired or negotiated, in total, 203 million hectares of land worldwide (ILC, 2012). Not far from this figure, Oxfam refers to 227 million hectares acquired since 2000 worldwide (Oxfam, 2011). With regards to Africa, the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) estimated that foreign investors had acquired at least 20 million hectares in Africa in between 2007 to 2009 (FAO, 2009). In 2010 the World Bank estimated that about 45 million hectares had been acquired since 2008; most of these land deals were for areas ranging between 10,000 and 200,000 hectares. The land grabbed for agriculture is constantly increasing and is currently reported (May 2012) to range between 32.7 and 82.2 million hectares, depending on whether only completed or also ongoing property-right transactions are accounted for (Rullia et al., 2013). These fragmented and to some extends contradicted figures have proven the lack of transparency regarding such issues as always done in a secret way with top leaders in most African countries. It worth mentioning that the land grabbing is done with limited or no consultation, lacking of adequate compensation, and without seeking opportunities to create new jobs for local producers (Cotula, 2009; World Bank, 2010).Several factors contributed to the rapid increase in land grabbing. These include massive population growth, food insecurity, global financial crises, climatic changes and urbanization (Elhadary and Obeng-Odoom, 2012). According to Shete and Rutten (2015) soaring grain prices in 2007/08 and fear for not accessing sufficient food for their citizens have fuelled the quest for large-scale arable land acquisition. In the same line Abebe (2012) notes that the primary factor behind land grab in recent years is the threats to global food security and the steady increase in the price of food globally. But for Daniel and Mittal (2009) there are only three main trends driving the land grab movement: the rush by increasingly food-insecure nations to secure their food supply; the surging demand for agro-fuels and other energy and manufacturing demands; and the sharp rise in investment in both the land market and the soft commodities market. Not far from the previous drivers Mann and Smaller (2010) indicated that the new investment strategy is more strongly driven by food, water and energy security. From what it has been said it seems that securing food mainly after the crisis in 2008 is the major drivers behind land grabbing elsewhere. Since the 2008 surge in food prices, foreign interest in agricultural land has increased and, in less than a year, investors have expressed interest in and acquired some 56 million hectares of land, of which 29 million were in sub-Saharan Africa in 2010 (World Bank, 2010; Elhadary and Obeng-Odoom, 2012). This implies that securing food in the long term, especially for land and/or water-scarce countries is a major driver that forced for example, Gulf (oil) Countries to invest land in Sudan (Antonelli et al., 2015).Several researchers have mentioned that despite its global nature, most of land grabbing is located in developing countries (Elhadary and Obeng-Odoom, 2012), and evidence suggests that considerable land areas are indeed targeted in developing countries (Nolte, 2014). Owing to the fact that cultivatable land worldwide is limited (Cotula et al., 2009) with the exception of large tracts of land in Sub-Saharan Africa and Latin America and, to a lesser extent, East Asia (FAO, 2011; Antonelli et al., 2015). This image enhanced by the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI) as it has reported that foreign investors sought or secured between 15 million and 20 million hectares of farmland in the developing world between 2006 and the middle of 2009 (Daniel and Mittal, 2009). This gives explanation why current land investors are targeting countries with abundant land and water resources, such as Sudan (Umbadda, 2014). Under the pretext of development, having hard currency and securing food for all Arab countries, huge communal land in Sudan were leased or sold to in and outside investors. Thus, the major objective of this paper is to broaden the knowledge in the above mentioned issue and find out its implication on local livelihood in developing countries taking Sudan as an example. The paper also investigates the process of land acquisitions, its implication of communal livelihood and how existing land tenure facilitates the grabbing of communal land. Given the fact the very few articles written on land grabbing in Sudan, this paper will contribute to the ongoing debate and open chances for more research. To fulfill the above objectives the paper is organized into six sections. The first section is an introduction followed by methodology. The third section is on land grabbing in the context of land governance in Sudan. The implication of land grabbing will be discussed in section four. Section five is about the discussion and the final section is about conclusion.

2. Methodology

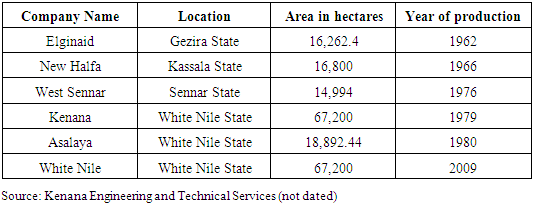

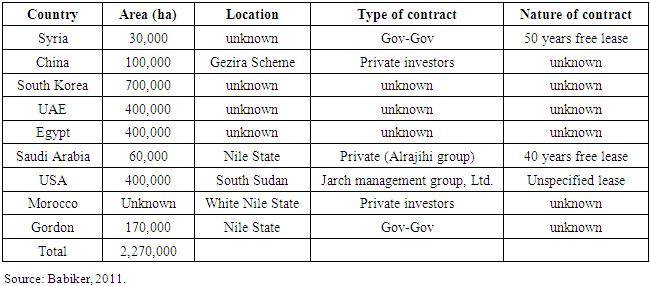

- Methodologically, the paper is based mainly on a desk review of a recent and comprehensive literature written on land grabbing worldwide. This also supported and enhanced by personal observation and experiences of authors in land tenure issues in Africa. To have reliable data, the paper used figures collected by international organizations. Land grapping in the context of land tenure policy in SudanAcquiring large-land for agriculture and other purposes like mining or industry is not a new in Sudan. It can be traced back to the 19th century; however, but it is still going on today. There are signs that this process will continue in the future (Babiker, 2011). Since its independence Sudan has embarked on amending the land tenure system and even introduced new laws to facilitate land acquisition (Elhadary, 2010). Use and access to land in Sudan as well as in most of African countries is governed by two overlapping and contradicting laws. These are “traditional” “communal” “customary” and “official” “formal” “statuary” or “state”. (for more details in land tenure issues see (Elhadary 2010; Elhadary and Samat, 2011; Elhadary, 2014; El Amin, 2016). Recently several African countries including Sudan have embarked on legalizing the communal right. In Sudan the situation is still vague especially after the introduction of land Act 1970. This act declares that the land or “unregistered land” is for all under the control of government (Elhadary, 2010). This means that if well implemented, ending completely the system of communal land tenure. However, this system has proved very resilient, and is still widely applied in many rural areas (Elhadary, 2010; Elhadary, 2015). Up to the present time, large group of people is still believe in communal right and that land is theirs while the state insisted that this system is no longer valid and it becomes part of the historical legacy of the country (Elhadary, 2007; Elhadary, 2010). Accordingly, the government usually allocates land to the investors, rich people and their loyalties without taking into consideration the historical rights of local people. The reality has shown that the government of Sudan enforces this act when there is an interest otherwise the situation is accepted as it was before 1970. For example, if there is a conflict over land right between the investors and communal users, the government refers to the act of 1970 and asks for official document which is hardly to find under the system of communal right. Thus, the winner in this case is the investors and of course the loser is the local producers. This led Wallin (2014) to state that it is primarily the poor and marginal people who are forced to sacrifice their lifestyles and traditions, for the sake of modernity and growth, without adequate compensation for their losses. In this situation El Amin, (2016) affirmed that the state legislation has created land tenure dualism simultaneously incorporating both the practice of customary tenure pursued by farming and pastoralist communities and the legal status of these communal lands as state-owned. This foggy situation led Sudanese and non-Sudanese to invest (grab) heavily on communal land. In this line Sulieman (2015) stated that the successive Sudanese governments have a long history in supporting land grabbing under different names and justifications. The unregistered Land acts of 1970 followed by abolition of native administration in 1971 and the introduction of Ministerial Act in 1996are some implemented Acts to facilitate land grabbing in Sudan. These acts provide the state legal right to control the communal land and more importantly remove any chance of legal redress against the state (Elhadary, 2010). As it says, no court is competent to deal with any suit, claim or procedures on land ownership against the government or any registered owner of investment land allocated to him (Ayoup, 2006; Egemi, 2006). It is important to note that the Ministerial Act 1996 transfers the functions of leasing unregistered land from federal level to local institutions at state level (Sulieman, 2013; Sulieman, 2015). This act has been implemented after the adoption of federal system in 1994 when Sudan was divided into 26 states; sixteen in the north and ten in the South. This Act implies that even the State has a power to lease land in “legal” way without even referring to the centre to get the approval. The Act also gave the authority to the minister of agriculture in Gedarif State to legalize large scale mechanized farming for 25 years leasehold (Sulieman, 2015). Parallel to the land acts, the government has recently introduced the National Investment Encouragement Act 2013 to ensure more grabbing of communal land. This Act provides comfortable environment and eliminate most of the constraints facing investment process. Moreover, it says that the land allotted for the project shall be handed over within maximum period of one month. Not only that, the investors may also owned land if fulfilling some specific purposes. This idea is highlighted by Elzobier, (2014) when he stated that the current Sudanese laws do not permit the ownership of land to foreigners. However, the new law will allow land ownership under specific conditions to serious investors. In the light of this, El Amin (2016) stated that the act gives foreign investors immunity from prosecution and arrest and approves the right of foreign investors to own Sudanese land. The Act goes even further to mentioned that the council is responsible to stand on behalf of foreign investors in case of objections by individuals, ministries, government institutions and local communities regarding land or in the case of initiation of court proceedings against investors to regain communal land granted by the government. The act also provides tariff exemption and an exceptional exemption from taxes for a period of ten years (Sudan Ministry of Investment, 2016). The Investment Act turned a blind eye in dealing with communal right and did not give them rooms to participate in decision making. This Act reflects clearly that the government is planning to lease or “sell” lands to domestic and foreign investors confidentially. This appears from the outstanding facilities given to the investors and from finalization of all the complicated processes in only thirty days. Moreover, the Act provides the investors with full power to use communal land without taking care of the previous land users thus, opening the door very broadly to both Sudanese (government officials or government affiliation) and non – Sudanese investors to grab more pastoral land in Sudan. According to El Amin (2016) the current state tendency to put state legal ownership over communal lands into effect for large scale sale or lease to investors amounts to denying Sudanese pastoralists and farming communities of their land use rights established for generations. The following section provides some figures about land grabbing in Sudan. Increasing hard currency, development and ensuring food security are some drivers mentioned by Sudanese government in justifying the lease of large farming to the investors. Most of the underlying reasons are stated to be food security and increasing the country’s agricultural exports (Sulieman, 2015). This slogan has been repeated even today in the local and regional media with some modifications “Sudan has an ambition not to feed their local people only but to secure food for all Arab countries”. In the light of these drivers coupled with the above mentioned investment facilities, several irrigated and non-irrigated schemes have been implemented in Sudan usually at the expense of land related to local communities (pastoralists) (Elhadary, 2010). Sugar schemes companies of Elginaid, New Halfa, West Sennar, Kenana, Asalaya, and lately White Nile Sugar are some of the irrigated schemes established in communal land (table 1).

|

|

3. Discussion

- Land tenure system in Sudan has amended several times aiming not secure it for local communities, but to provide the state full power to control and distribute land when and where it perceives fits, normally to investors and their affiliations. The Unregistered Land Act 1970 followed by the deterioration of native administration then the introduction of Ministerial Act of 1996 are some of the laws that negatively impacted on the livelihood of local communities. The weakening of the native administration, a representative body stand on behalf of pastoral communities to protect their right to land, has completely eroded the culture of communal land system and further led to political marginalization. The hijacking of the local representative institutions coupled with wide spread of literacy often make local producers more vulnerable and their voices are hardly to be heard. In such situations, the traditional role of local leaders as mediators and supporters of their community is totally eroded, giving the government a golden chance to lease or even sell land to their supporters and foreign investors. The introduction of land Investment Act of 2013 has killed the last hope of local communities and has left them vulnerable to more land right abuse. This recent act has paved the way for national and foreign investors to access “owned” more land in Sudan. It seems that the government is seeking hard currency rather than food security or “development”. The collapse of Sudan economy owing to the separation of South has encouraged the government to search for any source of revenue even if it is against their entire population wish to compensate for the great loss of oil revenue. It is expected that the parasitic investment in Sudan will lead to secure food, generate new jobs, create good infrastructure, produce advanced technology and reserve the environment. The reality shows that these benefits are not achieved in the case of Sudan. The paper is not against the local or foreign investment; however it calls for an implantation for a win-win situation. This approach ensures that increasing investment in farming will generate economic opportunities to both sending and receiving countries if well managed. Several research institutions and international governance agencies have proposed ways to make the land grab phenomenon a win-win situation, in which food-insecure nations will increase their access to food resources while benefiting “host” nations through investments in the form of improved agricultural infrastructure and increased employment opportunities (Daniel and Mittal, 2009). The high jacking of pastoral right, lack of transparency and corruption in selling or leasing land led the paper to use the term “grabbing” instead of “investment” or “acquisition”. The violation of communal right has impacted negatively on the pastoral livelihood and triggering the conflict among most of pastoral areas in Sudan. In the absence of transparency and accountability communal lands are often disposed investors in deals unknown to the public and the communities concerned (Elzobier, 2014). Lack of access to land forced local producers to engage in casual labour, informal urban sector and in some cases work as seasonal labours in big farming in Gedarif, White Nile, and Blue Nile States, while some of them turn to traditional gold mining. Unlike some African countries that formulated legislations to allow local communities to participate in the current trend of investment, Sudan does not even recognize local communities’ right. A growing number of countries have enacted legislation or policies requiring consultation and consent with affected communities. Under Mozambique’s Land Act, community consultation must be undertaken regardless of whether the land has been registered. Ghana and Tanzania have also enacted laws that include local communities in the decision-making. Sudan is in the same line with failed experiences like Ethiopia and Liberia. Coulta (2013) mentioned that in Ethiopia the government has forced tens of thousands of people off their land, and given it to ‘investors’ in 2012. Also, in Liberia, around 169,000 hectares had allegedly been given to a British palm oil company, without consulting over 7,000 people who have lived on the land for several generations.In a country where a number of its population depends on land in securing their livelihood, it is unfair to open the door widely for foreign investment. The government of Sudan should think carefully before selling or leasing land to the investors. Sudan is in an urgent need to facilitate accessing land to local producers and legalizing such right. It is not rational to lease a land for 99 years and give full chance to investors to grow whatever they like. This is even contradicted with concept of sustainable development where the right of the coming generation is fixed. The trend of current grabbing coupled with the huge debt means a form of a new colonization which is even danger that was in the past. In a country like Sudan where more than half of its people live in rural areas and depends on land to secure their livelihood actions to ignore such right is a ruinous. The government has to think in a win-win situation and has to adopt cost benefit analysis when it comes to lease land. It is true that the state will access a number of hard currency but how much the government pay to secure food for their entire people, ensure security and settle political conflict. Land is indispensable asset for local community, thus depriving them from this right means devastation to the whole sector. The development of agricultural schemes and the construction of large dams have eroded most of the strategies adopted by the local producers and disturb their traditional lifestyles of subsistence economy. Several animal routes have been closed by expansion of unorganized schemes. The construction of dams has forced large populations to relocate to foreign areas and adapt to new methods of more mechanized agriculture (Wallin, 2014). There is an urgent need to address the parasitic increasing of land grabbing or ruin occurs for all. This should be through the adoption of the concept of good governance. Also international institutions have to shoulder their responsibilities in implementing laws regarding human right.

4. Conclusions

- This paper highlighted the current trend of land acquisition “grabbing” by demotic or foreign investors in developing countries including Sudan. The paper is not against such acquisition for securing food in hosting and sending countries if a win-win situation for all stakeholders is ensured. Evidences from Sudan have shown that land acquisition is on increase and often at the expense of the right of the local communities. This parasitic economy lacks transparency, accountability and above all neglect the existing land rights of local communities. Sudan has introduces and amends land Acts to speed up the rate of grabbing, instead of enforcing principles that may lead to maximize the interests of all stakeholders. Leasing or selling communal lands has been negatively impacted on pastoral livelihood and in some cases fueling conflicts and tensions against domestic and foreign investors. Without considering the needs of the country and protecting the legal right of pastoral communities securing food through land grabbing will not be achieved. The paper also proposes that Sudan does not endure to massive land acquisition as there are several issues need to be tackled. First and foremost communal land tenure system needs to be legalized. Furthermore, the ways pastoral economy adapted to the harsh environment has to be confirmed and appreciated. This system is in harmony with the socio-economic characteristics and the ecosystem of Sudan. Thus, for Sudan pastoral economy is more relevant than “big” schemes especially when it comes to food security and social peace. If Sudan is interested in adopting the slogan “getting big or going out”; private – public partnership is more suitable than leasing land for 99 years. Sudan as well as the other African countries should consider the importance of food for their security. Nobody knows, in the future, food might replace real weapons against developing countries.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML