-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

World Environment

p-ISSN: 2163-1573 e-ISSN: 2163-1581

2016; 6(1): 19-24

doi:10.5923/j.env.20160601.03

Risk Management, Indigenous Knowledge and Biodiversity Conservation in Fadama Areas: The Case of Karshi and Baddeggi

Jake Dan-Azumi

National Institute for Legislative Studies, Nigeria

Correspondence to: Jake Dan-Azumi , National Institute for Legislative Studies, Nigeria.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2016 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Faced by multiple stressors such as climate variability, policy inconsistency and economic globalization among others, smallholders in developing countries are constantly seeking ways to adapt and reduce the vulnerability of their farming systems. Indigenous knowledge systems have provided the basis for efficient and cost effective resource management for many centuries. In this study of two fadama communities in Northern Nigeria, findings reveal the significant role and value indigenous knowledge in improving the resilience and adaptive capacity of fadama agricultural systems especially in light of increasing pressures, both natural and man-made. These farmers provide an excellent example of how local knowledge can contribute in the quest for sustainable systems through the promotion of adaptive strategies for resource management.

Keywords: Fadama, Indigenous knowledge, Risk management, Biodiversity conservation, Agricultural sustainability

Cite this paper: Jake Dan-Azumi , Risk Management, Indigenous Knowledge and Biodiversity Conservation in Fadama Areas: The Case of Karshi and Baddeggi, World Environment, Vol. 6 No. 1, 2016, pp. 19-24. doi: 10.5923/j.env.20160601.03.

1. Introduction

- Vulnerability refers to a system’s susceptibility to harm or the potential for loss within it (Smit et al., 1999, Luers et al., 2003). Many factors have been found to undermine the stability of agriculture and hence increase the vulnerability of smallholders. For instance, climate change can negatively affect smallholders by undermining their environmental capacity to produce while economic crises can affect them by increasing income risks and reducing their purchasing power (Adger, 1999, Dercon, 1999, Todaro, 2001, Skoufias, 2003).Over time, different societies evolved certain knowledge systems that are unique to them and sometimes distinct but not necessarily contradictory to international knowledge systems that allow them to manage risk, reduce vulnerability and conserve biodiversity (Devereux and Maxwell, 2001, OECD, 2005, Ferguson, 2006, IPCC, 2007).These knowledge systems were dynamic in resource management and agricultural production (Warren, 1991, Flavier et al., 1995) as well as cost-effective, participatory, sustainable and adaptive (Hunn, 1993, Robinson and Herbert, 2001). More so, the focus of indigenous agriculture and resource management is improving system resilience, i.e., a system’s capacity to adapt to change while maintaining its functions and control (Carpenter et al., 2001, Gunderson and Holling, 2001). Resilience and the adaptive capacity of a farming system are also closely related to the concept of sustainability (Folke et al., 2002).For centuries, many smallholders in developing countries have relied on small floodplains (fadama in Hausa1) to harness water for farming and construct feasible ecological systems that were socially controlled (Sandberg, 2004, Tockner and Stanford, 2002). These systems are mostly based on traditional agricultural methods and indigenous knowledge systems and consisted of: shared knowledge of “diversity of flood heights and onset times in various fields; drainage and fertility properties of the various soils; place and timing of vermin attacks; the flood resistance properties of seed varieties, especially rice; traditional land tenure mechanisms” (Sandberg, 1974). Fadama lands have continuously come under pressure from natural and man-made factors that include rapid population growth, drought, land degradation, expansion of cultivation on fragile forest cover, soil erosion, loss of soil fertility on arable lands, insufficient food production (FAO and IITA, 1999, Ewuim et al., 1998). Other pressures faced by smallholders in fadama areas are conflicts arising from competing land uses, intensification of agricultural activities by farmers, pastoralists, fisher-folks and other fadama users (Ardo, 2004). Faced with the dual problem of structural poverty and hunger, aggravated by the pressures mentioned above, smallholders in Northern Nigeria are continually seeking new ways to survive and protect their livelihoods. This often means reliance on indigenous knowledge as a tool for reducing risk and conserving biodiversity.

2. Methods and Materials

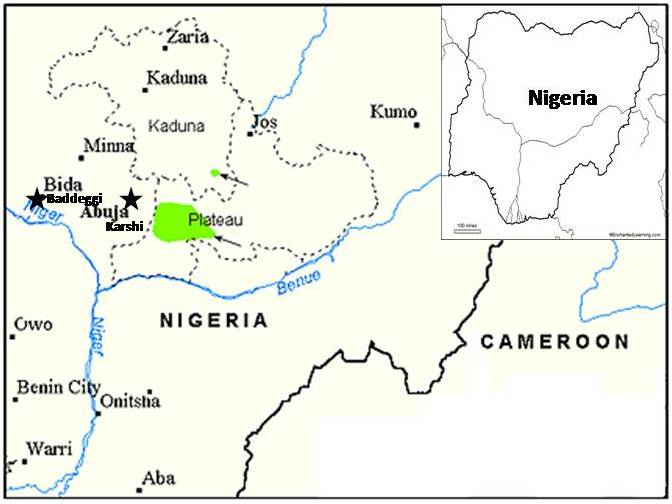

- ParticipantsThe participants in this research were rural farmers in two villages in North-Central Nigeria: Karshi and Baddeggi, two small agrarian communities in North Central Nigeria. Karshi, the core study area and the place that provided the bulk of the data for the research, is one of the satellite towns of Abuja, Nigeria’s capital city. It covers a land area of 8,000 square kilometres and is located in the middle of the country. Abuja falls within latitude 7° 25' N and 9° 20° North of the equator and longitude 5° 45' and 7° 39'. Karshi is one of the typical settlements in Abuja and consists mainly of rural indigenous communities engaged mostly in farming and related activities. Gwari, Gwandera and Gwandu are Karshi’s predominant ethnic groups.Baddeggi is a small district of Bida town, the second largest city in Niger State. Bida sits on the Bako River, one of the several minor tributaries of the Niger River. It is approximately 100 km/60 mi southwest of Minna and 200 km/120 mi northeast of Ilorin and falls on Latitude 9° 4' 60 N, Longitude: 6° 1' 0 E. Baddeggi is a major trade centre for rice, which is mainly cultivated in the fadamas of the Niger and Kaduna rivers. It is predominantly inhabited by the Nupe people. Most of the inhabitants of Karshi and Baddeggi are farmers involved in both upland and lowland (fadama) farming. Baddeggi served as a comparative study of the similarities and differences with Karshi and the underlining general structure that generates them.Data and MethodsMethodological Triangulation was used in this research. It is pluralistic, mixing the mainly qualitative data (generated from in-depth interviews) with quantitative data (generated from survey methods) (Olsen, 2004). This is in line with the realist epistemology/ontology that sees reality as stratified; on the one hand social objects have a real ongoing existence irrespective of what we know of them, while on the other hand they are affected by the way they are construed (Sayer, 2000). Triangulation considers as false the claim that quantitative and qualitative methodologies are incompatible (Silverman, 1993) and seeks to avoid simple generalizations by enabling a more comprehensive understanding of social phenomenon carter (Carter and New, 2004).Over a period of four months, 47 people were interviewed in-depth in Karshi and 21 in Baddeggi. The research strategy consisted of mixed techniques led principally by a core interview schedule which was complemented by a follow-up strategy, involving survey techniques used to accurately measure the demographic features of the research participants and the extent of agrochemical use. The research methodology was Grounded Theory (GT) as the research was concerned with expanding an explanation of fadama agriculture through the identification of its key elements and then categorizing the relationships of those elements to the context and process of the experiment (Strauss and Corbin, 1994, Charmaz, 2000). The data collected was mainly analysed using the qualitative GT technique which helped to achieve a more critical and reflexive interpretation of the statistics generated and hence helped to avoid the often simple, general and impersonal nature of statistics.

| Figure 1. Location of Surveyed Farms in North Central Nigeria |

3. Results and Discussions

- Risk Management (rage asara) in Fadama AgricultureFadama users (like most smallholders in developing countries) face increased challenges from biophysical and socio-economic pressures which makes their systems vulnerable. The shocks to fadama agriculture can be attributed to multiscalar stressors that include climate change (e.g. changing rainfall patterns and drought), policy shocks (e.g. inconsistent and insufficient policies with regards inputs and subsidies and the difficulty in securing affordable inputs), institutional weakness (e.g. poor infrastructure and services), population explosion and man-made disasters (e.g. erosion due to road construction) among others. To effectively reduce risk and cope in this changing environment, fadama users adapt by taking in new ideas and testing, adopting or discarding them according to their needs. One of the overriding concerns of fadama users is not simply yield maximization but risk management as farmers are constantly adapting local knowledge and farming practices to meet new needs. This is referred to as ragenasara in Hausa and literarily translates to risk reduction and is meant to ensure that output is consistent over long periods of time. As with many smallholders, the most important risks (defined as an uncertainty that matters (Harwood et al., 1999)) facing fadama users relate to (1) production/yield due to the reliance of agriculture on unpredictable factors such as climate and rain (2) institutional risks, i.e. changes in policies and regulations that directly affect smallholders, e.g. policies on fertilizer subsidies and (3) price/market, i.e. fluctuations in prices. Thus, risk management in fadama involves choosing among alternatives that reduce these risks and promote the welfare of the farmer. The main risk management strategies of many fadama users are centred on agricultural adaptation (risk coping and management). An important asset in achieving stability and ensuring system resilience in fadama areas is knowledge of: soil types, soil fertility, types and prevalence of weeds and importantly of rainfall patterns. The choice of farming methods and practices (for soil and water conservation), their development, modification or outright rejection by the farmers in Karshi and Baddeggi, depend on the extent to which they mitigate risk and ensure stability in the farming system both in the interim but also in the long-run. Biophysical and climatic factors (low and often erratic rainfall patterns) and available tools and resources determine what approach the farmers take to resource management. For instance, farmers often choose to broadcast seeds and save the labour and environmental damage that result from excessive land tillage. In the face of alternative choices, farmers decide on methods that are less demanding of labour, more cost effective, sustainable and above all, practicable and attainable. They also engage in soil and water conservation as described above in order to reduce risk.The centrality of risk management to fadama farming is reflected in the diversification of the farming system (e.g. mixed cropping-use of different crop varieties and integrated farming). Such diversification reduces vulnerability of the farming system and enhances farmers’ coping strategies. The advantage of mixed cropping in mitigating risk is that it results in efficient use of water and reduces the risk of complete crop failure due to climatic or other biophysical events. Other varieties of mixed farming practiced in the study areas involves the combination of short cycle animals and crops discussed above. Other farm level adaptations include: adjustments in planting and harvesting dates and use of labour saving strategies (use of simple tools and community labour (gaiya)). Also, crop choice by fadama farmers strikes a balance between risk minimization and profit maximization as will be seen in the poise of choice between high and early performance hybrid seeds and local resistant varieties. Another important risk mitigation strategy is diversification to ease the effects of erratic and low rainfall patterns through increased use of irrigation and simple irrigation technologies (e.g. China type pumps) so as to efficiently use available water and planting of drought resistant varieties (e.g. New Rice for Africa (NERRICA)).Another example of diversification is seen in the ability of fadama users to engage not only with and in different farming systems but also different forms of occupation (artisanship, drivers, butchers, etc.). This means that fadama farmers ensure resilience by incorporating structural change so as to perpetuate their production models (van der Leeuw and Aschan-Leygonie, 2000). In general, diversification is done either through actual increased diversification or by careful crop management to mitigate the negative effects of climactic variations.Fadama agriculture is dynamic and continuously changing to adapt to new crop varieties and cropping patterns. Farmers test new crop cultivars alongside existing varieties, thereby improving the genetic pool of existing crops and maximizing resistance to disease, pest and drought. However, hybrid seed varieties (favoured by official government policy) are competing with traditional fadama varieties (such as local egg-plants, vegetables and rice, etc.) and they threaten to reduce genetic diversity. Findings from both Karshi and Baddeggi show that flexibility characterizes decision making regarding resource management. For instance, they use agrochemicals, hybrid seed varieties and other inputs alongside traditional methods to bolster their productive capacity. This flexibility has been found to be the characteristic feature of environmental management in the savannahs and arid regions of Nigeria (Kolawole, 1991). Fadama farmers also adapt with regards the market as explained by an extension worker in Baddeggi:Biodiversity Conservation in Fadama AreasOne of the most critical roles of IK in fadama areas is in biodiversity conservation and risk management. This is mainly through mitigation and adaptation. Fadama smallholders were found to be excellent managers of agricultural resources based on experience and inherited knowledge. Traditional risk management techniques in fadama areas carried out as natural resources conservation measures also serve the dual purpose of “reducing the emissions of GHG from anthropogenic sources, and enhancing carbon “sink” both of which are important in light of climate change (Nyong et al., 2007). Also, IK is central to efficient environmental resources management practices that include low tillage, mixed cropped, crop and job diversification, integrated farming and adjustment in planting/harvesting times. In turn, these methods help fadama users to cope with or adjust to the impact of changes and hence reduce vulnerability.Integral to the evolution of IK in the area of land management is a consideration for expected gain over time. In other words, farmers in both Karshi and Baddeggi choose methods that optimize their output while ensuring stability over time. This is even more so with population growth and disappearance of the fallow system which had hitherto encouraged the development of forests. Decisions involving soil management (identifying fertile soil and improving depleted ones) are based on IK. Soil qualities such as colour (kala), texture, fertility (karfi) moisture content (lema), and the types of weed that grow on it, all form part of the comprehensive traditional method of soil assessment. Based on these properties, the farmers decide when to plant (beginning, mid or end of the rainy season) and the type of soil improvement methods to use. Thus, they are able to mitigate risks and increase/maintain their productivity.In addition to these traditional adaptive measures however, members of both Karshi and Baddeggi communities also draw from technological innovations and external inputs (discussed below) in order to function under new and challenging conditions. All these show the ability of small-scale indigenous farmers to experiment, improve and develop new systems specific to their context (Haugerud and Collinson, 1991, Lamola, 1992, McCorkle and McClure, 1992). In general, the logic of traditional methods and practices are now better understood and appreciated among agricultural experts in the West (Altieri, 1987).Fadama agriculture relies on local resources and knowledge to conserve biodiversity. For instance, traditional knowledge in the area of seed selection helps to preserve genetic information of local varieties and indigenous species. The process of seed is usually complex and draws from IK. Thus, seed selection is a careful process meant to protect the phenological integrity of traditional seed varieties. The qualities of the seeds which include ear characteristics, presence of insect holes, size, earliness, shape, colour, are all considered important in seed selection. A striking element of the IK of the people of Karshi and Baddeggi with regard to agricultural production is that it is extensive resulting from experimentation and practical judgement, developed and modified over generations in line with the environmental and climactic challenges that confront them. The agricultural practices and methods of two communities are not arbitrary but the result of continuous experimentations. For instance, farmers first experiment with new seed varieties/cultivars on a limited scale to test suitability and output before widespread adoption. Through experimentation, the farmers are able to breed better varieties of crops and animals and promote diversity through the control of genetic resources. The farmers are able to prioritize and make distinction between seed crops grown strictly for monetary purposes and those grown for consumption in the house, use for local brew and rituals. Decision Making among Smallholders in Fadama AreasFadama agriculture provides not just a means of livelihood for farmers but is also an important tool of empowerment. It enables farmers to take control of and make decisions about their livelihoods. This is particularly true for women for whom farming is an important tool for self-expression and socio-economic empowerment no matter how limited. The acceptance, rejection or modification of technology and other development inputs among farmers in Karshi and Baddeggi was found outto be carefully constructed based on their understanding of their conditions and circumstances. In other words, they never totally accept nor reject development plans in a haphazard manner but consider how these agree with their environment and experience. Hence, they negotiate meaning and are able to sift through the options available to them in order to choose what they consider to be the best option. They are also able to modify whatever ‘innovation’ they are introduced to such that it fits into their millennia of practice. For instance, they accept hybrid seeds but restrict its use to only the commercial while keeping the local variety for food and brew. Similarly, many of the farmers use external inputs such as fertilizer and pesticide for their expediency only but maintain the use of organic fertilizer like compost and animal manure. In fact, several farmers realize that chemical fertilizer affects the taste of crops like banana and also vegetables and fruits in general. The agency called into play when negotiating meaning can be seen in the farmers’ perception of themselves and their abilities. This is often juxtaposed with the ‘other’s’ (government, development workers) perception of them which then forms the basis for power relation/exchange. Despite their perceived sense of self-worth, ability and knowledge, they regard themselves as powerless in the face of so called ‘superior’ mainstream milieu. For instance, the farmers loathe that they are undervalued and unsupported despite their potentials and the fact that they provide the food needs of most of the population. They were angered by the decision of the Nigerian government to import rice worth $1.3 billion in 2009. For them, it signified misplaced priority and policy which should be more inward-looking and targeted at self-reliance through local production rather than dependence on importation.

4. Conclusions

- Despite its role in maintaining livelihoods and indeed their contributions to global knowledge systems in such areas as medicine, IK has long been undervalued (Jackson, 1987, Liebman, 1987, Slikkerveer, 1989, Warren, 1989, Slikkerveer and Adams, 1996, Slikkerveer and Quah, 2005). Similarly, in spite of recent discourse on the validity of IK, findings from both Karshi and Baddeggi show that in practice this has not yet happened as seen in the structural and institutional neglect of indigenous systems whose potentials have not been fully utilized in the development process. They are often regarded as out-dated and unproductive. Hence, development and agricultural policies always stress technology transfer at the expense of local experiences and practices. This is reflected in, for instance, the promotion of hybrid seeds as against resilient local varieties, agrochemicals in place of cultural and biological methods of pest/disease control and mechanization in place of sustainable practices such as minimum tillage and ridge planting. Yet, IK, as shown above, is vital both in reducing risk and conserving biodiversity.Like any knowledge system, nevertheless, IK is limited and amenable to improvement. Similarly, not all of what is contained in the IK canon might be relevant in fast changing times and climatic fluctuations. The challenge is to put concerted effort in the study of these systems in order to understand and test them with the view to harnessing the great potentials they present. Many of the traditional methods discussed above are cost effective, sustainable, and practical (Richards, 1989, Warren, 1989, National Research Council, 1992, Warren, 1992). Thus, research in the area of traditional crop and livestock management systems need to be encouraged and expanded especially in academic circles, specifically in Africa. It is by doing this that IK can be reclaimed, especially those important agricultural practices that have or are gradually disappearing but which are vital in enhancing smallholder resilience and hence their productivity and sustainability. What is required is a creative and honest engagement of IKS with mainstream modern knowledge system so as to create a system that best responds to the needs of people in the developing world.

Note

- 1. Hausa is a Chadic language belonging to the Afro-Asiatic language family and it is one of the three major languages spoken mostly in Northern Nigeria and across West Africa.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML