-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

World Environment

p-ISSN: 2163-1573 e-ISSN: 2163-1581

2015; 5(1): 28-38

doi:10.5923/j.env.20150501.04

Assessment of the Public Participation in Solving Environmental Problems in Delta State, Nigeria

Shehu Nuruden Muhammed1, Ali Demirci2

1Department Name of Organization, Federal University, Dutse Jigawa State, Nigeria

2Department of Geography, Fatih University, Istanbul, Turkey

Correspondence to: Ali Demirci, Department of Geography, Fatih University, Istanbul, Turkey.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2015 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

Delta State has long been facing many environmental problems, mainly from oil extraction activities by the multinational companies which have, to a large extent affected the ecological environment of the region. The aim of this study is to understand both public perceptions of environmental problems in Delta State, as well as its willingness to solve these problems. A survey consisting of 11 questions was conducted over 250 people in three local government areas in Delta State in Nigeria. According to the results of the survey, oil spillage was found to be the most important environmental problem with its effects on water, soil, and biological resources in the study area. The results also revealed a greater public willingness to participate in efforts to solve the environmental problems in its surroundings. The study concludes that there is a need for a much more robust public awareness campaign, as well as provision of basic necessities to the general public. This will likely enhance public participation, thereby ensuring environmental sustainability.

Keywords: Environmental problems, Public participation, Assessment, Nigeria

Cite this paper: Shehu Nuruden Muhammed, Ali Demirci, Assessment of the Public Participation in Solving Environmental Problems in Delta State, Nigeria, World Environment, Vol. 5 No. 1, 2015, pp. 28-38. doi: 10.5923/j.env.20150501.04.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- The most pronounced environmental problems facing the Delta State in Nigeria are related to oil extraction activities of the multinational companies. Here, many forest areas were cleared for either heavy machine installation or running of pipelines from one destination to another [1-3]. These environmental problems resulted from rampant incidents of oil spillage and sporadic spread of petroleum resources within the natural environment. This in turn caused a great deal of damage to the entire ecosystem, including aqueous environments, aquatic animals, as well as the health status of the concerned communities which in most cases can lead to death [4].Statistics have indicated that about 3000 oil spill situations were reported by multinational oil companies operating in the Niger Delta between 1976 and 1999. This has led to the spillage of more than 2 million barrels of crude oil [5]. Most of the percentage spills occurred offshore (69%). About a quarter was in swamps and 6% spilled on barren land. As stated by Jike (2004) [1], the issue of oil bunkering by the local communities, expressed as “sabotage,” has also been one of the contributing factors to these pressing environmental problems. Gas flaring, unfriendly toxic substances which are sprayed into the environment that affects ecosystems and biodiversity, is another process that pollutes the environment. This releases large amount of methane with a large global warming potential, accompanied by greenhouse gases such as carbon dioxide, of which Nigeria was estimated to have emitted more than 34.38 million metric tons in 2002, which account for about 50% of all industrial emissions and 30% of the total carbon dioxide emissions in Nigeria [6]. This environmental degradation has already caused many problems for the society, some of which are high rates of unemployment, loss of jobs, escalated rate of poverty, communal conflicts, political unrests, rural-urban migration, deterioration of water resources, public health, and infrastructure [7-10].The daily extraction of petroleum products, coupled with excessive spillage from the crisscross of the running pipelines has displaced a lot of farmland, aquatic animals, and even societies living in their inherited homelands in Delta State, because large areas are occupied by roads, pipelines, and houses for workers [11, 12]. The rampant oil spillage also affects vast agricultural lands and fish ponds, which ultimately result in poor ecological/environmental well-being. As seen in many oil producing communities across the Delta area, the contamination of river bodies through oil spillages could consequently exterminate the aquatic animals, thereby affecting the local indigenous population, whose livelihood depends on rivers and other surrounding natural environment [13]. Large, productive agricultural lands were already lost and turned into barren areas due to oil spillages and pipeline leakages. Even some applications to clean the environment from oil spills may cause damage to the environment. For example, as Amadi and Tamuno (1999) expressed, even chemicals that are used to clean the environment from oil destroy soil, crops, and aquatic animals if used recklessly [7].The federal government of Nigeria, coupled with the concerned oil multinational companies operating in these areas, has been making an effort to remediate these pressing environmental problems. Different agencies have been established in Nigeria to combat the pressing effects of environmental problems, mostly concerning oil production and spillage. The Niger Delta Development Board (NDDB) was among the first agencies created with that purpose in 1963. Oil Producting Area Development Commission (OMPADEC) and Niger Delta Development Commission (NDDC) are among the other important initiatives established in 1993 and 2000 respectively. The Ministry of the Niger Delta, established in 2008, was another important organization dealing with the oil related environmental problems in Delta State. Different strategies and developmental projects have been implemented by these agencies over the last few decades in order to tackle the environmental problems in Delta State [5]. For example, the multinational oil companies have been paying huge amounts of tax in compensation to host communities for the many environmental hazards introduced in the process of their oil drilling operations, even though this is lower than international standards [14]. Despite various efforts made by the concerned authorities and the multinational companies, the issue of environmental degradation and insecurity in the Delta area does not seem to have significantly subsided [15]. This situation of continuous environmental problems in the Delta State confirms that a different approach should be considered in order to attain a lasting solution towards solving these environmental problems. Public participation is among the strategies that may be taken into consideration to mobilize society in cooperation with the responsible authorities to tackle environmental problems in Delta State. Since oil-related environmental problems impact society with different problems, the solution should involve all the related partners together with public and responsible institutions. As stated by Schulenburg (1998), the public should be allowed to be thoughtful and creative in taking actions towards the solution on issues that directly or indirectly affects their mode of living [16]. When people are active in environmental decision-making, we can make sure that decisions are made in a timely fashion to solve environmental problems.Public participation is regarded as a social learning process, linking the building blocks of development [17]. It includes active participation, empowerment and sustainability, social learning as well as public involvement in decision making. According to Kumar (2002, 22) public participation is “a process that includes people's engagement in the process of decision making, program implementation, as well as sharing of the benefit of development programs and in an effort to evaluate these programs [18].” Arnstein (1969) defines public participation as “the redistribution of power that enables the have-not citizens to be deliberately included in the future plan [19].” The world bank describes the same concept as a process by which people, especially disadvantaged people, can exercise an influence over policy formulation, design alternatives, investment choices, management, and monitoring of development interventions in the communities [20]. Public participation describes the utmost need of pulling ideas together in order to solve environmental problems. Through public participation, the level of environmental information flow will be improved between authorities and the general public. As Rowe and Frewer (2000) addressed, this flow can be assured through three ways, namely public communication, public consultation, and public participation [21]. Public participation has great importance for society. As Sithole (2004) asserted, it greatly assists in addressing the needs of the entire interested/affected public, inspires citizen-focused or self-centered service delivery, enables the proper utilization of available resources, and creates a room for proper understanding of when, where and why a certain project or decision was carried out [22]. These benefits of public participation seem obvious. The controversy, however, is how best to carry out this process. Arnstein (1975) stressed that the success of public participation depends on the power to influence decision-making [23]. In some instances, the mere provision of opportunities to make comments at public hearings or to participate as members of pressure groups/labor unions satisfies the public’s desire to participate in environmental decision making. On the other hand the need for more elaborate public involvement is quite necessary. Effective public participation can be achieved when there is full awareness/information about a certain decision or project being carried out within a particular community. Effective public participation can be realized when the public understands why, when, where, and how they may be involved in making decisions on actions that affects their lives [24]. Successful public participation requires a very well-structured information flow between institutions and public, as well as efficient working conditions and mechanisms to ensure the opinions and interests of public are heard, taken seriously, and made effective for all decisions concerning the public.Different strategies are implemented in different countries to achieve public participation. In Germany, for instance, a high level of public engagement was identified in the country’s official publications [25]. Many provinces in Germany legally endorse citizen participation primarily issues of urban planning, as it was stated in the German building law of 1976 which clearly outlined that the general public should be consulted on issues that concerns developmental projects [26]. Because of some important regulations, the level of civic engagement in Germany is high compared to many other countries. Thirty-four percent of the total population was civically engaged in decision making in this country [27].Public participation is a well-known concept that is taken seriously in developed countries to help make decisions about environmental issues concerning society. However, in Nigeria’s Delta state, it is not understood properly, nor it is being used as an approach to helping solve environmental problems. The need for public participation in solving environmental problems in Delta State cannot be over-emphasized. It was observed by Abdulkareem (2005) that most of the policies introduced by the national assembly on gas flaring and other related environmental protection issues in the Delta region for the past 22 years were unsuccessful due to poor and insufficient planning, political and cultural issues [28]. Furthermore, a lack of public participation on issues concerning environmental protection has played a significant role in ruining the government policies and programs. Some individuals, for instance, engaged in creating havoc by vandalizing some of the running pipelines, using these for illegal oil tapping in the name of looking for a way to earn a living or make quick money. The illegal oil bunkering, pipeline vandalism and destruction have already reached a level that in many ways hampers the entire community’s social, economic and environmental well-being. This indicates that the government and concerned environmental agencies alone cannot single-handedly solve the pressing environmental problems in the Delta region without public participation. However, we do not know how much the public is aware of the environmental problems in their regions, nor to what extend they will be willing to cooperate with the responsible state institutions to solve these problems in Delta State. This study was aimed at understanding how the public perceives environmental problems, and to what extend they are willing to work for solutions in Delta State in Nigeria.

2. Study Area and Method

- The study was conducted in Delta State, an oil-producing state situated in the Niger delta region of south-southern part of Nigeria, between Latitudes 5000’ and 6030’ north and Longitudes 5000’ and 6045’ east coordinates. The state presently covers a landmass of approximately 18,050 km2. The study area is characterized by its natural resources, consisting mainly of rich oil reserves and favorable weather conditions support year-round agricultural production. About 50% of the active labor force engaged in agriculture [29] in the area; however, as Ugochukwu (2008) stated, much of the traditional farming practices, like bush fallowing and shifting cultivation, are distracted due to the reduction of farmland caused by petroleum mining [30].

| Figure 1. Map of Delta State showing Local Government Areas [31] |

3. Results

3.1. Location, Age, and Gender

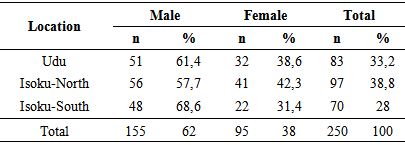

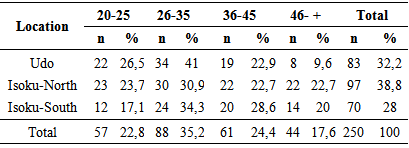

- Two hundred and fifty questionnaires were distributed to two hundred and fifty different respondents. There were 155 male (62%) and 95 female (38%) respondents across the study area. As seen in Table 1, 83 people participated in the study from Udu with 51 (61,4%) males and 32 (38,6%) females. The number of people who responded to survey questions in the Isoku-North local government was 97, with 56 (57,7%) males and 41 (42,3%) females. Whereas Isoku-south local government has a total number of 70 respondents, 48 (68,6%) males and 22 (31,4%) females respectively. Each respondent represents the views and opinions of a particular family, since the survey was carried out with only one person from each family. However, some respondents discussed the questions together with their family members before answering them.

|

|

3.2. Education and Family Size

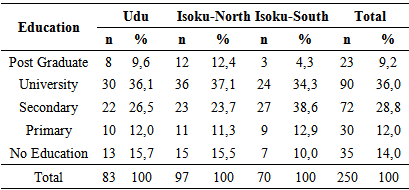

- Table 3 shows the educational level of respondents by their locations. As the table shows, there was a high literacy level among the general respondents, with nearly half of the population (45,2%) holding a university or post graduate degree. Almost one fourth of all respondents (28,8%) were secondary school graduates, whereas 12% have completed their primary education. Only 14% of the respondents can be considered illiterate with no education. No significant difference was observed within the specific locations in terms of educational attainment of the respondents.

|

|

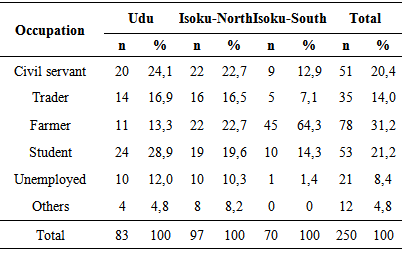

3.3. Economic Situations

- The occupations of the respondents range from civil servants, traders, farmers, and students to those who are unemployed. As seen in Table 5, farmers constitute the largest occupation group with 31,2% of all the respondents, followed by students and civil servants, with 21,2% and 20,4% respectively. Fourteen percent of respondents indicated their occupations as a trader while only 8,4% of them said they were unemployed. The occupation of the respondents changed among different locations. For example, Isoku-South has the highest respondents that were farmers with about 64,3%, followed by Isoku-North and Udu local governments with 22,7% and 11% respectively.

|

|

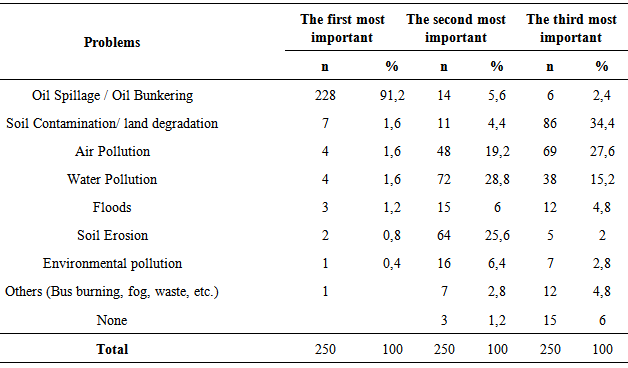

3.4. Perceptions of the Respondents about Environmental Problems

- The study provided an understanding of which environmental problems affect people most in the study area. The participants were asked to name the three most important problems in their environments. As seen in Table 7, oil spillage / bunkering has been the most disastrous and devastating environmental problem facing the community in the study area.

|

|

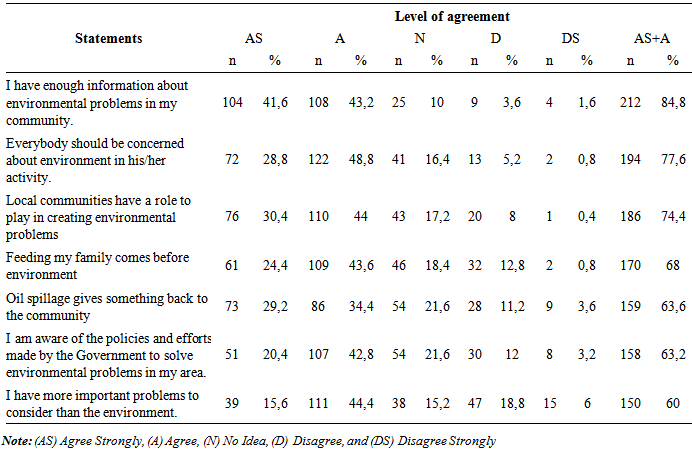

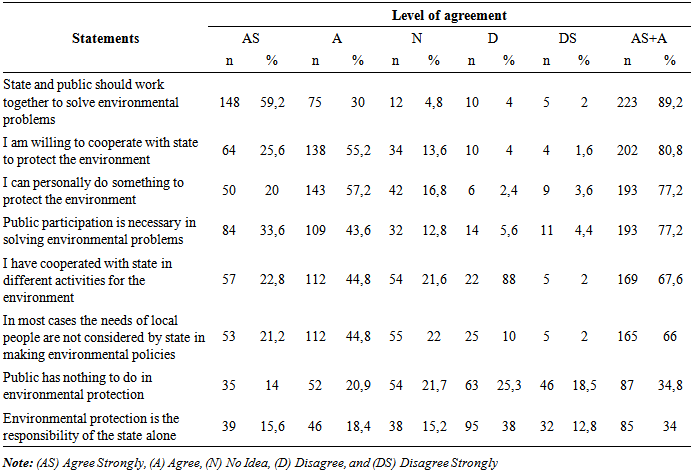

3.5. Perceptions of the Respondents about Public Participation

- Table 9 shows the opinions of respondents regarding statements of public participation, as well as their willingness to work for the solution of the environmental problems. As seen in the table, a great majority of respondents (89,2%) believe that the state and the public should work together to solve environmental problems. Among respondents, 80,8% are willing to cooperate with the state to protect the environment. The study further revealed that a great majority of respondents (77,2%) believe that public participation is necessary to solving environmental problems, and the same number of people indicated that they can personally do something to protect the environment. It is also important to see that more than half of the respondents (67,6%) cooperated with the state in the past in different activities to protect the environment. The results in Table 9 also show that respondents generally believe in the importance of cooperation between public and states to tackle environmental problems: only about one-third of respondents (34,8%) think that the public has nothing to do in environmental protection, while nearly the same number of respondents (34%) believe that environmental protection is the responsibility of the state alone. Although the respondents seem willing to take responsibility in solving environmental problems, the majority of them (66%) believe that in most cases, the needs of local people are not considered by the state in making environmental policies (Table 9).

|

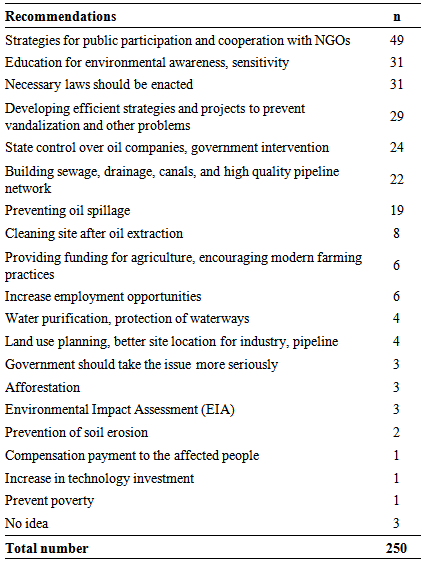

3.6. Recommendation of the Respondents for Solving Environmental Problems

- Table 10 shows the recommendations of respondents for solving environmental problems. As seen in the table, about one fifth of the respondents (49 people) addressed the importance of developing more efficient strategies to increase public participation and cooperation with NGOs for solving environmental problems. Thirty-one people highlighted the role of education to increase awareness and sensitivity for environmental protection, while the same number of people said that necessary laws should be enacted to solve environmental problems. Twenty nine people also addressed the development of efficient strategies to prevent vandalization and 24 people even said that state control over oil companies should be increased. Building drainage systems and high quality pipeline network and preventing oil spillage are the other recommendations highlighted by 22 and 19 respondents respectively. Among the other recommendations made by a relatively small number of respondents are providing funding for agriculture, increasing employment opportunities, land use planning, afforestation, increasing investment in technology, and preventing poverty. Only three respondents offered no recommendation (Table 10).

|

4. Discussion

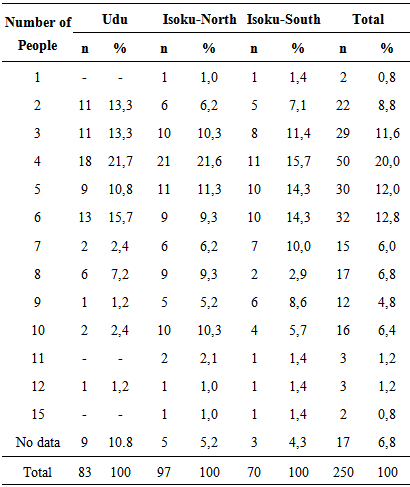

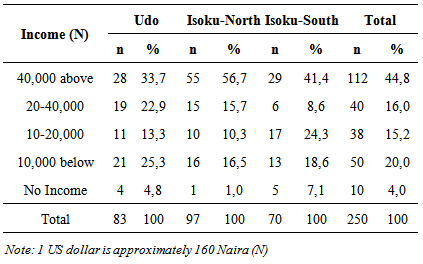

- Delta State in Nigeria has been experiencing numerous social, economic, and environmental problems resulting mainly from oil extracting activities, despite the efforts of many different governmental initiatives to solve the problems. Many different projects have been implemented in the area by responsible authorities over the last half century. However, these efforts frequently end in failure to find lasting solutions for environmental problems. The insufficiency in tackling environmental problems requires searching for and applying different strategies in order to understand real environmental problems with their versatile consequences in society, and to find permanent solutions. Whatever strategy is developed, public participation is a must. This is necessary to ensure that such strategies, developed by responsible governmental institutions, will be understood and applied properly and will result in finding lasting solutions to the ongoing environmental problems. The aim of this study, therefore, is to understand how the public perceives environmental problems and to what extend they are willing to cooperate with state authorities for their solutions in Delta State in Nigeria. The study provided a clear understanding of the environmental problems which have been affecting the local community within the study area. The study was carried out in three different locations in Delta State in Nigeria, where oil spillage and bunkering has already caused many problems over local people and the environment. This has been addressed in the results of the survey, which was conducted in a sample size of over 250 individuals, representing 1300 people living together in the same house as a family. A great majority of the respondents (91,2%) cited oil spillage and bunkering as the top most important environmental problem, with its direct effect on their economic, social, and environmental well-being. Oil spillage and bunkering causes rapid environmental degradation due to the fact that a lot of fuel is spilled around from damaged pipes, causing excessive contamination in the entire ecosystem with its water, soil, and biological resources [32]. Water pollution is the second most important environmental problem, as cited by approximately one fourth of the respondents (28,8%). This problem, caused mainly by oil spillage, first contaminates running streams and rivers which are the main water resources for drinking and agriculture. It subsequently leads to the creation of waterborne diseases like typhoid fever and other related diseases in society [4]. Soil erosion, air pollution, soil contamination, and land degradation are the other environmental problems which were cited frequently by the respondents with their direct effects on their society.The study provided significant results which will lead to having more effective strategies for solving environmental problems in the study area with the involvement of the public. First of all, what we understood in the study is that the public is well aware of the environmental problems within their surrounding areas. About 85% of respondents agreed that they had enough information about environmental problems. As such, it will require some effort in society to create greater environmental awareness for solving these pressing problems, even though there were some differences between the respondents with respect to educational levels. More educated respondents seemed to have better awareness about the environmental problems than the less educated ones. This addresses the need to improve the educational conditions in the study area, in order to increase the environmental awareness of the public. This will, in the end, facilitate public participation in solving environmental problems. Another important result of the study is the apparent readiness of the respondents to take responsibility to create and to solve the problems. A great majority of respondents believe that everybody should be concerned about the environment in their activities and that local communities have a role to play in creating environmental problems. It should be noted, however, that the results differed slightly between different income and educational groups of the respondents. In general, the wealthier and more educated respondents tend to feel greater personal responsibility for the creation and resolution of environmental problems than less wealthy and educated respondents. Apart from increasing the educational level, this shows the importance of increasing the economic welfare of the society in order to make them more responsible against environmental problems and more willing to work for their solutions.The study revealed that economic conditions of the people living in the study area is not very good, with more than half of the respondents having less than 250 US dollars as their monthly family income. As seen in the responses, this has affected the perceptions of the public towards environmental problems negatively. About two thirds of the respondents think that they have more important problems to consider than the environment, and that feeding their family comes before the environment. This figure changes slightly among the respondents with a different family income. As such, more wealthy respondents did not agree with this statement as much as the less wealthy groups. This further shows that despite some awareness of the environmental condition, some individuals were less conscious of protecting the environment, instead being more focused on what and how to feed their families. This concern took priority, even at the expense of the environment. Therefore, the implication here is that the environment will end up being degraded by the majority of people in the community in the name of looking for daily bread, despite great efforts and resources made for environmental protection. As such, the set targets to achieve by environmental protection agencies will likely fail. This situation once again addresses the need to increase the economic welfare of society in order to have their cooperation in implementing lasting solutions for environmental problems.The willingness of the public to cooperate with the state is crucial for thorough public participation. The study revealed that a great majority of respondents believe that the state and the public should work together to solve environmental problems; they are willing to cooperate with the state for such a purpose. This shows that despite the economic situation and hardship condition of the people, there remains trust between the general public and the government. This trust indicates a willingness to work together to help salvage the environment from its present situation. The majority of the respondents also believe that public participation is necessary for solving environmental problems and they are ready to do something to protect the environment. As seen from this result, the majority of respondents believe that the government cannot solve these environmental problems alone. Therefore, the public must work with the government to ensure environmental safety and protection.

5. Conclusions

- Based on the results revealed from the study, it can be concluded that the majority of Delta State people were aware of the pressing environmental problems facing them. They were therefore willing to cooperate with the government at different levels to provide a lasting solution towards these problems, most specifically when governments were willing to provide the basic necessities of education and more job opportunities to the general public. As stated by Ogunbode and Arnold (2012), this will help enhance environmental sustainability [33].The need for public participation in solving environmental problems in Delta state cannot be over emphasized. This shows the utmost need for pooling ideas and resources together in order to solve the current environmental problems. Therefore, we would like to make the following recommendations in order to achieve proper public participation in Delta State to solve environmental problems.• A public participation unit and sub-units should be established in state institutions, mainly in the Ministry of Environment, with the sole aim of enhancing the level of public awareness about environmental issues.• There must be an efficient communication between concerned authorities and the public about any kind of environmental decisions which will affect the day to day life of the society.• The state must earn the public’s trust by showing that their opinions are valued in making laws and decisions, and in taking action, on the environment.• Comprehensive programs should be organized regularly in both national and local media stations as well as other communication channels in order to enlighten the public about their need for participation in solving environmental problems in Delta State.• NGOs and responsible governmental authorities should cooperate to pool resources and ideas together in order to come up with good initiatives, strategies, and programs to encourage public participation.• Local community leaders should become involved in mobilizing the public to participate in efforts to solve environmental problems. • A culture of public participation should be developed within the Delta State community, with more effective communication in order to bridge the gap between the government and the general public.• The local authorities should always offer the public the general information which will facilitate their involvement in a meaningful way. • The standard of living should be increased in Delta State by providing more job opportunities. Businesses should be encouraged to be helpful in reducing the devastating level of pipeline vandalism. • Public awareness should be increased regarding environmental problems and the role of public participation in solving these problems through formal and informal education.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML