-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

World Environment

p-ISSN: 2163-1573 e-ISSN: 2163-1581

2014; 4(4): 185-198

doi:10.5923/j.env.20140404.05

Potential of Environmental Education through Agriculture to Increase the Adaptability and Resilience of Individuals

Hiroto Ito, Qiyan Wang, Masakazu Yamashita

Department of Environmental Systems Science, Doshisha University, Kyoto, Japan

Correspondence to: Masakazu Yamashita, Department of Environmental Systems Science, Doshisha University, Kyoto, Japan.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2014 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

Although human beings have accomplished significant progress in science and technology in recent years, a variety of problems have also occurred as a result. Since these environmental problems are closely associated with people’s daily lives, changes in their awareness and “environmentally friendly” behaviors are required. As it is necessary to promote environmental education to nurture people who can take such actions, the present paper discusses what is required for today’s environmental education, namely, training people who can take actions to solve problems. Considering that there are a significant number of people who have not yet taken actions despite their interest in environmental issues, it is not difficult to understand the significance of such education. The promotion of environmental education in collaboration with society, not at the individual level, is also considered to be important. The present paper discusses environmental education through agriculture, examines its effectiveness using data and case examples, and proposes its improvement based on obtained results. The present study has been conducted to identify what is required for environmental education and the results suggested that environmental education through agriculture is effective. Although collaboration with local governments and communities is required, in addition to efforts by universities, to implement environmental education through agriculture, environmental education has significant potential, and it is significant to conduct it for environmental conservation.

Keywords: Environment, Education, Agriculture, Adaptability

Cite this paper: Hiroto Ito, Qiyan Wang, Masakazu Yamashita, Potential of Environmental Education through Agriculture to Increase the Adaptability and Resilience of Individuals, World Environment, Vol. 4 No. 4, 2014, pp. 185-198. doi: 10.5923/j.env.20140404.05.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- There has been significant progress in science and technology in human society. This progress has allowed people, particularly those in developed countries, to live a convenient and comfortable life. Food is always available at convenience stores and supermarkets, and a wide variety of new products, including automobiles and electrical appliances, have been developed. In this era of material abundance, people place great emphasis on profit, given that this is an income-oriented society. On the other hand, people are faced with a variety of problems, including deforestation, shortages of food and water, and waste disposal. Companies produce and distribute eco-products, which are aimed, at least officially, to address these problems. Nowadays, not a single day passes without the phrases “eco-friendly products” and “eco-products” being mentioned on TV. Will the development of “eco-products” by those companies and their use by consumers solve environmental problems? We do not think so. In our opinion, the environmental burden of “environmentally friendly” products is similar to or even greater than that of other products. For example, as long as a person drives an automobile, it makes little difference whether the amount of its CO2 emissions is large or small [1]. Significant amounts of energy and resources are required to develop even low-emission automobiles, and, if these automobiles sell well, even larger amounts of energy and resources will be required. Trading in a used automobile for a new one generates waste. A production and consumption cycle like this does not solve environmental problems after all.What is necessary to solve environmental problems in a real sense, then? What is the core of environmental issues in the first place? It is considered to be people’s awareness. As environmental issues become increasingly discussed, public awareness of environmental problems increases [2]. However, people are still unable to take appropriate actions. We consider that it is necessary to change people’s attitudes to improve this situation. However, it is not easy to change public awareness. It is particularly difficult for modern people living in an advanced society for a long time and who are accustomed to it to change their environmental attitudes. In this context, the present study focuses on children, who will play important roles in the future. The implementation of environmental education for young children may be the key to solving environmental problems. Environmental education through “agriculture” in particular is a clue to possible solutions because agriculture is most closely associated with food - one of the essentials for human beings.Agricultural experience helps children become familiar with and interested in nature. The agricultural cycle, including sowing, sprouting, fruiting, and the consumption of crops by humans, allows them to recognize that they are also part of the ecosystem, as well as the continuity of the lives of organisms. Since some environmental problems, such as global warming, deforestation, and food shortages, are related to agriculture, students undergoing the above-mentioned type of education are not only encouraged to experience nature. Many subjects can also be developed into environmental issues. Because collaboration with the community, as well as schools, is essential for the implementation of agriculture, society as a whole can become involved in this form of education. Environmental education through agriculture is considered to be effective from these points of view.The present paper reviews the history and status of environmental education to examine what is required, and discusses the potential of environmental education through “agriculture”. The paper also proposes desirable forms of education, based on data and case examples.

2. History of Environmental Education

2.1. Trends in Environmental Education Globally

- The first international movement that can be regarded as involving environmental education is the “United Nations Conference on the Human Environment” held in Stockholm in 1972 (Stockholm Conference). This conference, participated with representatives of 114 countries, was held with the following background: “As development and industrialization around the world significantly advanced in the 1960s, a wide variety of environmental problems occurred, and it was predicted that natural resources, on which we had been heavily relying, would be depleted. People all over the world should collaborate with each other to address these problems because humans may be annihilated unless effective measures are developed” [3]. The conference aimed to promote the ability of people to take actions for environmental protection: “The purpose of environmental education is to train people who take consistent and steady actions to manage and control the surrounding environment within the capability of each person” [4]. The 19 principles of the Declaration on the Human Environment, adopted by the conference, suggested the importance of environmental education, and the adopted action plan recommended important guidelines on school curriculums for environmental education. The guidelines suggested that “it is necessary to introduce new educational materials to environmental subjects (such as natural science, nature, and human geography), and recommend biological learning approaches”. The recommendation also suggested that it is also necessary to introduce subjects designed to teach ecological concepts: “Since human beings are part of the natural ecosystem after all, damage caused to the environment by humans will eventually have adverse effects on them”, and subjects developed with a strong sense of purpose: “The natural ecosystem on earth is facing a crisis, and its functions must be restored.” Since the conference, researchers on environmental education and governments have thoroughly discussed the concepts of environmental education and its methods of instruction [5].Following the Stockholm Conference, the International Environmental Education Workshop (Belgrade Workshop) was held in Belgrade, former Yugoslavia [6], and the Intergovernmental Conference on Environmental Education (Tbilisi Conference) was held in Tbilisi, the former Republic of Georgia, in 1975 [7]. The Belgrade Workshop, in which the Belgrade Charter was adopted, was positioned as the preparatory meeting of the Tbilisi Conference. The charter states that, as an ultimate goal to be accomplished by environmental actions, “it is necessary to improve all ecological relationships, including the relationship of humanity with nature and people with each other”. The following six objectives: “awareness”, “knowledge”, “attitude”, “skills”, “evaluation ability”, and “participation”, and eight guiding principles of environmental education are also stated in the charter. As its notable characteristics, the Belgrade Workshop states that it is necessary to encourage individuals to change their attitudes toward environmental problems and take actions, as well as organizing the stages for environmental actions systematically [8].In the Tbilisi Conference, held in response to the results of the adoption of the Belgrade Charter, important global issues were also discussed. As for environmental education in particular, the conference suggested an approach of discussing environmental issues as those related to humans, in addition to the provision of education centered on nature conservation, using four keywords: “values”, “conscience”, “environmental ethics”, and “people’s way of life” [9]. The Tbilisi Declaration set the following three challenging goals: 1) increase public awareness of and concern over economic, social, political, and ecological mutual relationships between urban and local areas, 2) provide all individuals with opportunities to learn knowledge, values, attitudes, ability for implementation, and skills, and 3) develop new patterns of environmental actions for individuals, groups, and society [10]. Whereas six objectives of environmental education are included in the Belgrade Charter, the Tbilisi Declaration stated the following five objectives: “awareness”, “knowledge”, “attitudes”, “skills”, and “participation”. The Belgrade Charter encourages individuals to take actions, whereas the Tbilisi Declaration facilitates both individual and social actions while recognizing environmental problems as social issues. Therefore, the declaration stresses that people should be provided with sufficient opportunities for social experience in organized and systematic education to help them solve environmental problems [11]. These concepts comprise the basis of environmental education that is currently implemented.

2.2. Trends in Environmental Education in Japan

- In Japan, education on pollution control measures had been provided prior to the initiation of environmental education. This was because a number of pollution problems had arisen in the country, including the Ashio Copper Mine Pollution incident in 1877 and four major pollution-related diseases in the 1960s. Education for nature conservation was also implemented at that time, from the viewpoint of nature protection. With the economic growth of Japan, following its recovery from World War II, and significant progress in nature development, there was increasing concern that the beautiful nature of the country might be lost. In the following years, the Committee for Nature Conservation and Liaison was established, organizing academic conferences to promote both nature conservation and related education [12]. Both education on pollution and that for the promotion of nature conservation were implemented as environmental education in a broad sense. However, in most cases, education on environmental pollution was provided to help identify, examine, and address the sources of pollution, or as education on identifying the causes. People who had received such education tended to view and recognize “pollution” as an issue irrelevant to them [13]. In fact, the measures to address hazardous organic mercury discharged from some plants may not be an issue that concerned all Japanese people. However, since the 1980s, people living in urban areas have been faced with various forms of urban-type, daily life-related pollution, including “river pollution”, “air pollution”, and “waste treatment”. To respond to these problems, environmental education to help people learn “environmental problems” that occurred in living environments in the community started to be provided [14]. In 1988, the former Environment Agency (current Ministry of Environment) submitted a report of a discussion session on environmental education to promote environmental education. The definition of environmental education stated in the report: “Environmental education aims to encourage people to understand the relationship between humans and the environment, increase their awareness, and take actions in a responsible manner by providing them with support”, is basically consistent with the objectives and goals of environmental education described in the Belgrade Charter [15]. In response to requests from educators and the public to promote environmental education, the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology revised the curriculum guidelines, including the introduction of the “integrated learning program”. The integrated learning program allows for educators and teachers to develop creative classes according to the status of the community, school, and children, and implement unique educational activities based on them. Under the integrated learning system, interdisciplinary classes are held across boundaries among conventional subjects, such as the environment, international understanding, information, welfare, and health. Integrated learning programs for each academic year were fully initiated in elementary and junior high schools in 2002, and in high schools in 2003 [16]. Different from traditional education courses, teachers in charge of integrated learning classes establish their goals and develop programs, instead of using predetermined textbooks [17]. Although a number of schools hold integrated learning classes to implement environmental education, the subjects vary from school to school: the cultivation of flowers, activities for a clean environment and energy conservation, stocking rivers with cherry salmon, development of biotopes and farms, and production of compost. Although the conventional environmental education system allows for a high level of flexibility in classes, it also has some disadvantages: the appropriateness of classes and their effectiveness are questionable, and the quality of lessons may vary depending on the skill of the teacher.

2.3. What is Required for Environmental Education?

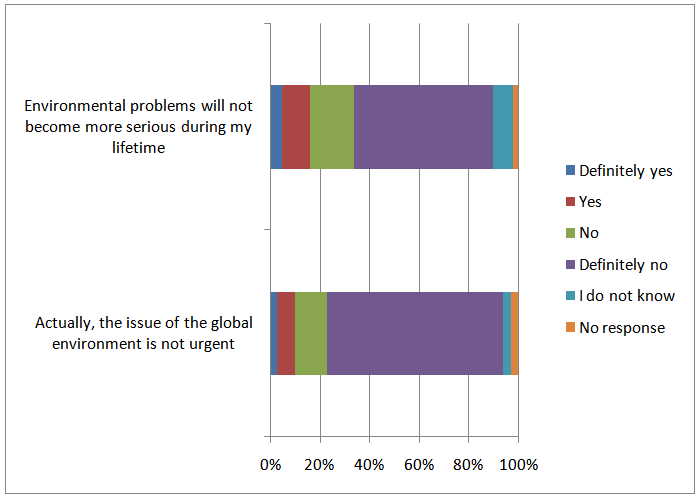

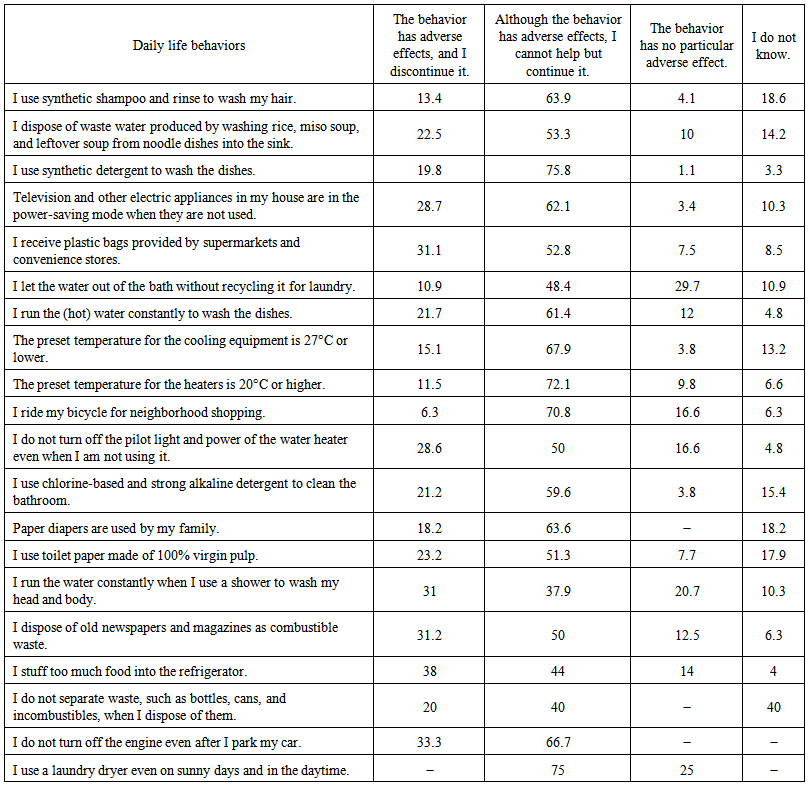

- As described in the preceding paragraphs, the concept of environmental education was created to solve a variety of problems attributed to significant progress in development and industrialization. Therefore, it is necessary to train people who: view themselves as part of the ecosystem, are determined to improve their awareness, recognize environmental problems as an issue relevant to them, understand environmental issues properly, and take actions to solve problems. In addition to improving the awareness of individuals, it is also important to collaborate with society to promote this form of education. As the objectives included in the Tbilisi Recommendation suggest, it is necessary to encourage people to undergo the following educational process: become interested in environmental issues, acquire accurate knowledge, improve their attitudes, develop required skills, and independently participate in activities that develop responsive measures. In recent years in particular, there have been gaps between people’s awareness of the environment and their behaviors. Figures 1 and 2 suggest that, although there are a large number of people interested in environmental issues, few of them have actually taken actions.

| Figure 1. Awareness of Japanese people toward global environmental problems [18] |

| Figure 2. Attitudes toward global environmental problems (cost awareness) [19] |

| Table 1. Awareness of the issue of environmental load-related behaviors [20] |

3. The Potential of Environmental Education through Agriculture

3.1. Reasons for the Promotion of Environmental Education through Agriculture

- This paragraph focuses on the advantages of environmental education through agriculture.The first advantage is the importance of experiences of nature. Nowadays, there are few places left in which children can directly experience nature. It has been pointed out that children living in large cities - a living environment principally consisting of concrete and roads paved with asphalt, cannot familiarize themselves with nature, and have difficulty understanding its functions [21]. Without an awareness of the “functions of nature”, people would not be able to recognize that humans are also part of the ecosystem. In her work, The Sense of Wonder, Rachel Carson described: “I firmly believe that ‘knowing’ is less than half as much important as ‘feeling’” [22]. Carson referred to the sense of wonder as the sensibility with which people are deeply moved by mysteries and wonders. She also stated: “Once the feelings of a person, including the sensitivity for beauty, sense of excitement experienced when encountering new or unknown things, consideration, compassion, acclaim, and affection, are aroused by experiencing something, the person becomes more eager to understand the subject. Knowledge acquired through such an experience is instilled in a person.” [23] She suggested that, if a person becomes deeply interested in nature through experiences of it, the person will be motivated to acquire knowledge. This is an example of the development of the objective stage from “awareness” into “knowledge” as stated in the Tbilisi Declaration, and suggests the importance of experiences of nature. However, such experiences alone do not solve the problem. This is indicated by the fact that today’s environmental destruction is often caused by adults who grew up surrounded by nature in childhood and had more opportunities to experience it. The problem is that the shift to “attitudes”, the third of the objective stages stated in the Tbilisi Declaration, has not yet been accomplished. A science and civilization-oriented society is a society in which people are closely associated with modern scientific thought, which was established in the 17th century, and scientific technologies in daily life; some people suggest that human-centric ideas and human supremacy, part of modern scientific thought, form the background to today’s environmental problems [24]. This is reflected in the fact that many people hesitate to lower their standard of living to address environmental problems, as shown in Figures 1 and 2 and Table 1. Most people cannot take environmental actions, presumably because they believe in the superiority of human beings to some extent, although it may be inappropriate to describe them as people with a self-centered idea or who believe in human supremacy. Another reason is that people are unable to relate to environmental problems as in the case of education on pollution described in 2-2. Experiences of agriculture are effective for people to improve their attitude. They can help people become aware of the continuity of the “lives of organisms”: sowing, sprouting, blossoming, fruiting, harvesting, and the consumption of crops by humans or the storage of seeds [25]. From agricultural experiences, people are expected to learn that they are also part of the ecosystem and receive benefits from nature. This will encourage them to be grateful to nature and improve their attitudes toward it. The present study focuses on environmental education through agriculture for the above-mentioned reasons.

3.2. Environmental Problems Identified through Agriculture

- Environmental education through agriculture is participation-based education. However, it has also been pointed out that participation-based education has the following disadvantage: learners tend to become satisfied with the act of experiencing something itself [26]. It has been pointed out that “educators are required to design programs, while developing the image of the person to be nurtured by environmental education, in which learners can move onto the next learning stage based on their experiences of nature” [27]. Environmental education through agriculture also allows educators to develop these programs. Some human behaviors that we perform in our daily lives may cause environmental destruction. Such behaviors can be understood by undergoing environmental education through agriculture. The present paper describes the potential of environmental education through agriculture, focusing on the above-mentioned points.(1) Global warming attributed to the increase in CO2 emissionsIn Japan, it has become increasingly easy to obtain food, including fast food. Now that all kinds of ingredients are available and a variety of cooking methods have been developed in this age of plenty, people’s diet has become diversified [28]. On the other hand, people have fewer opportunities to experience agriculture, production areas and places in which consumers live are separated, and they are less interested in ingredients and procedures involved in food processing. Environmental problems are partly caused by these circumstances. The following paragraph provides an example of this for tomatoes:According to an estimate, the amounts of CO2 emitted during the transportation of a specific amount of tomatoes from Saitama, Kumamoto, and Thailand to Tokyo Prefecture were 14, 207, and 6,944 g, respectively [29]. Imagine you purchase tomatoes at a supermarket in Tokyo. The amount of CO2 emitted when transporting tomatoes from Kumamoto Prefecture is approximately 15 times that when transporting them from Saitama Prefecture. The amount of CO2 emitted when transporting them from Thailand is approximately 500 times as large. This means that, if people purchase food produced in surrounding areas, that is, “local production for local consumption”, CO2 emissions will be reduced. In addition, cultivation under unheated and heated (in houses) conditions produces varying amounts of CO2 emissions. For example, the amount of CO2 emitted under unheated conditions was shown to be 192 grams, whereas 771 grams of CO2 was emitted under heated conditions in greenhouses [29]. This suggests that four times as much CO2 is emitted to produce vegetables under heated conditions in greenhouses. In this era, all kinds of vegetables are available in all seasons due to the advancement of science and technology. However, this convenience is obtained at the price of the above-mentioned disadvantage. To improve this situation, it is necessary for consumers to comprehend the process of the distribution of food to them, and purchase local products in season. Agricultural experience allows people to learn and comprehend this process, from production to consumption, and actually choose local products in season.(2) Deforestation due to changes in food cultureIn this paragraph, an example of deforestation in Malaysia is provided. The production of palm oil in Malaysia is continuing to increase. In 2005, it accounted for the largest part of the total oil production globally [30]. In Japan, the large use of palm oil started in the 1960s, when the production of Cup Noodle was initiated. Approximately 570,000 tons of palm oil is imported by Japan annually, mostly from Malaysia. In other words, the forests of Malaysia are being destroyed to produce palm oil that is exported to Japan. The tropical forests are being deforested to plant Elaeis guineensis, a type of palm tree used to produce palm oil. At least 3,000 hectares (approximately 620 times the size of Tokyo Dome) of land is required for an Elaeis guineensis plantation. In Japan, approximately 90% of palm oil produced from Elaeis guineensis is used for food manufacturing, such as the production of instant noodles, margarine, frying oil, chocolate, almonds, ice cream, and other processed foods [31].Then, the changes in food self-sufficiency is considered. The level of food self-sufficiency calculated based on the supplied heat was 79% in 1960, decreased to 60% in 1970, 53% in 1980, and 40% in 1998. Food self-sufficiency between 1998 and 2005 was maintained at 40% [32]. This suggests that food self-sufficiency started to decline around the same time as Japan started to import palm oil. As Japan’s long-established food culture shifted to a new one, its food self-sufficiency declined, and large-scale deforestation occurred. It is true that instant noodles are convenient and have a reasonable price. However, it is necessary for the Japanese to understand that these instant foods may cause environmental problems, to increase their food self-sufficiency, and to return to their traditional food culture.(3) Food crisisThe world is facing a food crisis. Against this background, the issue of biomass energy has been receiving attention in recent years. In America and Brazil, wheat and corn have been cultivated to produce energy to drive automobiles, not as food. As a result, the prices of many food products, including bread and other wheat products, mayonnaise, and oranges, have been rising. Although the level of food self-sufficiency in Japan is 40%, as described in the preceding paragraph, the country can withstand price hikes to some extent because it has accomplished significant economic development. Japan is affluent due to its technological and economic development, as well as industrialization. Although Japanese people are able to purchase food, their industrialization has caused a variety of environmental problems. What will happen if the prices of food products increase further? Will Japan further promote its industrialization to develop its economy? What will happen if a food exporter to Japan becomes unable to produce enough food surplus to domestic requirements to export some of it? The time may come when Japan cannot import food from other countries no matter how much money it is able to pay. What will Japan have left then? To avoid a situation like this, it is important for Japan to promote agriculture.Agriculture is associated with environmental problems, as suggested by a variety of issues, including global warming, deforestation, and food problems. Therefore, environmental education through agriculture allows people to acquire knowledge on these subjects. It also teaches children the significance of agriculture in a very effective manner. There is also a bill designed to increase the efficacy of environmental education through agriculture. The Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology has developed a policy to revise the School Lunch Act, which was originally established to improve nutrition, the following year, and place an emphasis on dietary education [33]. This revision includes a description of an approach to encourage people to utilize local ingredients and experience food production in order to increase their attachment to the local area. The revision of this law in 2008 is also expected to increase the significance of environmental education through agriculture.

3.3. Collaboration between Schools and the Community

- “Think globally. Act locally”. This is a term related to the implementation of environmental education. Although there are various theories as to who invented this phrase, it expresses the truth of environmental issues: various forms of urban-type, daily life-related pollution, such as air pollution, waste disposal, and water contamination, are caused by the behaviors of each person. What does “act locally” refer to? “Locally” in this paper refers to “in a particular space or place where a person grew up”. According to a dictionary, “locally” is defined as “being nearby or in the neighborhood”. In other words, the term refers to “being in the community”. The following paragraph discusses the significance of community utilization in environmental education through agriculture.Regarding the educational effects of a local community as educational material, a previous study suggests that “participation in ‘integrated learning’ utilizing educational materials unique to the community allows not only children but also schools, teachers, and the community itself to review their approaches for addressing various problems in society” [34]. According to another previous study, “Children, teachers, schools, and community residents learn many things and mature while developing mutual relationships in the process of solving problems. Since collaboration between schools and the community is essential for community-based integrated learning, it has varying characteristics unique to each community, and schools play important roles as sites for conferences and community meetings [35].” The greatest advantage of utilizing a local community is that not only children but also teachers and local residents can learn from it. The behaviors of adults, as well as those of children, are important to solve environmental problems because the action of each person makes a difference. As described in 2.1, the Tbilisi Declaration emphasizes the importance of implementing environmental education for society as a whole, rather than at the individual level. The significance of the shift from school-based to community-based environmental education is reflected in the declaration. One of the basic principles on environmental education in the Tbilisi Declaration states that “environmental problems should be discussed in a process that continues throughout the lifetime (lifetime learning including education provided in kindergartens, schools, and other places)” [36]. In other words, both adults and children, who will become adults in the future, are required to continue to learn about environmental problems. Education provided in the community allows them to do so. Since various technologies, techniques, and land are required for agriculture, collaboration with the community is essential. Considering these points, it is very important to collaborate with the community as well as schools.

4. Analyses of the Implementation of Environmental Education through Agriculture

4.1. Educational Effects of Agriculture Presented by Data

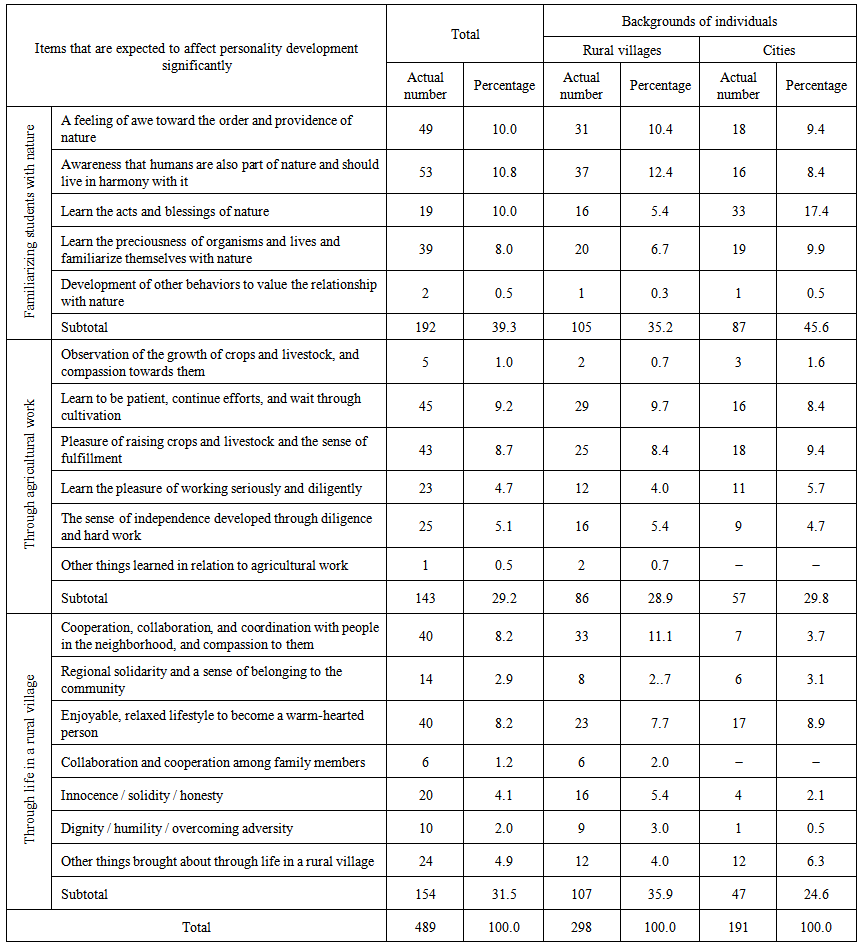

- The potential effects of environmental education through agriculture are proposed in the preceding paragraphs. This chapter examines such effects. A survey was conducted based on the hypothesis that agriculture has an inherent ability to nurture, teach, and train people, and the results are presented in Table 2 [37].

| Table 2. What can be taught through agriculture? [38] |

4.2. Analyses of Examples of the Implementation of Environmental Education

- This section discusses examples of current environmental education approaches through agriculture, and examines their advantages, efficacy, and potential improvements.(1) Example of Mogusadai Elementary School in Hino CityThis section first examines an example of collaboration between Ishizaka Farm House, a farm located in a village forest in Hino City, a suburb of Tokyo Prefecture, and Mogusadai Elementary School in the city. Mogusadai Elementary School, which aims to develop a crop-producing schoolyard, invited the Ishizaka family, self-sufficient farmers, as instructors. Ishizaka Farm House, which cultivates rice, vegetables, fruit, and herbs, and also keeps bees, has been operating for more than 500 years. The farm produces more than 100 varieties of crops, and almost everything is home-grown. That day, the first task was the preparation of seed potatoes. A potato is cut in half to prepare two seeds. However, it is necessary to sprinkle ash on the wet surfaces of the cross sections to disinfect and dry them. This task is assigned to children. A sense of responsibility is required to perform the task because, if the proper procedure is not conducted, the potatoes will not sprout. Prior to performing the task, children should be reminded of this. After the students completed their task, they headed for Ishizaka’s farmland. The moment the students stepped on the farmland, they were surprised by the softness of the soil. The soft soil is actually compost made by decaying a mixture of stacked fallen leaves and rice bran. Seed potatoes are usually buried at the depth of one seed potato. However, as it was still cold that day, seed potatoes were buried deeper.Children then moved to another field to learn about harvesting. They were surprised and impressed by spinach spread all over the field to be exposed to the sun and giant fork-shaped radishes, and harvested a variety of vegetables, including carrots and Chinese cabbages. At that time, the cheerful voices of the students were echoing over the field, and big smiles were on their faces. The harvested vegetables were washed with groundwater, cooked, and eaten. The students were able to experience the pleasure of harvesting crops and eating them. When the students returned to the school and touched the soil in the vegetable garden on the school grounds, they noticed large differences from the soil on Ishizaka Farm. Then, the students voluntarily started to pull out weeds, remove pebbles and garbage, and ploughed the ground with a hoe [40]. Although Mr. Ishizaka told us that he is not particularly interested in providing environmental education, this is a good example of it. Children were able to experience the power of nature directly, became interested in it, and finally took specific actions. They developed a sense of wonder, as described in [3-1], which is considered to have effectively motivated them. They recognized that they are also part of the ecosystem through the actions of planting seeds, harvesting crops, and eating them. It is significant that children perform their tasks under their own responsibility, which teaches them the complexity, difficulty, and hardship associated with the production of food. This type of education is meaningful in this era in which all kinds of convenient instant food are available, as described in [3-2]. Furthermore, children learn the mysterious power of nature with the support of the school and farmers, and cooperation between them helps develop a good relationship between the school and community. Even agricultural activities that are not intended for environmental education may have positive effects on this type of education.(2) Example of Yanominami Elementary SchoolYanominami Elementary School was designated as an educational institution for the “Hiroshima 2045 Peace & Create” project initiated in 1995 to mark the 50th anniversary of the 1945 atomic bombing of Hiroshima, and completed as the first among other project-related activities. Yanominami Elementary School was established in April 1998 as a branch of Yanonishi Elementary School. As the construction of the school was initiated with environmental education in mind, it has genuine paddy fields made from several dozen centimeters of soil on its rooftop. In addition to the paddy fields, the school also has gardens, fields for each class, and forests and ponds on the school grounds, which allow students of the school located in an urban area to experience nature. With the aim of nurturing sensitive children who can express themselves well in the above-mentioned school environment, the school as a whole implements various educational activities. The main subject is to conduct research on “integrated learning” designed to train those children.Specifically, first-year students learn while playing in the school including the grounds, and second graders learn from growing vegetables in the fields and gardens. Third graders learn from insects in the forests, and fourth graders learn by observing organisms living in ponds. Fifth graders learn from cultivating rice in paddy fields, and each sixth-year student decides on the theme for their task and learns in the process of addressing it. Students are encouraged to: pay attention to changes in the season, visit an agricultural high school in the neighborhood to learn how to grow vegetables, enjoy a traditional Japanese pot dish (called oden), including vegetables harvested from their fields, with their parents invited to the school, and receive guidance on rice cultivation from farmers as teachers. Following the harvesting of rice, a large-scale harvest festival is held with the support of parents and a stall of the community center. Environmental education is also developed into social studies, Japanese, science, music, and other subjects to help students learn in a complex manner. As a result, students cited paddy fields on rooftop, ponds, forests, and Japanese gardens as their favorite areas in the school, according to the results of a questionnaire survey. This suggests that close relationships are established between students and the above-mentioned places [41].Various forms of environmental education are conducted over a period of six years, and the students become familiar with nature. Furthermore, the school also actively promotes exchanges with the community, and develops environmental issues as school subjects into community studies. In the cultivation of rice, students experience almost all procedures: preparation of the soil, winnowing, planting rice seeds, growing rice seedlings, digging up the soil, letting water flow to paddy fields, rice planting, the management of water, pulling out weeds, drying harvested rice in the sun, husking, and rice milling, which allow them to recognize the hardship of the work. When students celebrate an abundant harvest in the harvest festival following this hardship, they feel a higher sense of achievement. However, there are some improvements to be made. Although students become attached to nature by experiencing agriculture, it is necessary to examine whether they can relate themselves and their daily habits to environmental problems. It is important to increase the effects of environmental education to motivate students to take environmental actions.(3) Example of Seitoku Elementary School in Amagasaki CitySeitoku Elementary School, along with Yanominami Elementary School, is surrounded by a unique natural environment for a school located in an urban area. The school’s farm environment is classified into the following five groups: (1) a farm environment referred to as the “School Farm” principally consisting of all-season vegetable gardens with pots, (2) paddy fields, (3) gardens in which seven spring and fall herbs are cultivated, (4) shelves for loofahs, and (5) horsetail gardens. In addition to these, the school has a rich natural environment, including three forests (one of them is a quasi-climax forest that is not managed, and another is a secondary [or second-growth] forest properly managed in the environment of village forests), three ponds, three brooks, and tree-lined streets. The following is a summary of programs that the students undergo on the school grounds as a natural environment [42]:1. Subject curriculumsSeventy-three classes associated with various subjects are held, utilizing the school grounds as a natural environment.2. Daily life curriculumThe curriculum aims to encourage students to familiarize themselves with nature during recess time and through cleaning activities. The curriculum includes unique activities: Let’s-be-friends Time/Green Time. In Let’s-be-friends and Green Time, children independently take care of animals and plants, including school farms, pet animals, and flowerbeds, while interacting with students of “Nakayoshi Class” in a different school year. Let’s-be-friends Time principally consists of breeding and cultivation activities in the morning. In Green Time, students conduct their assigned tasks for Nakayoshi Class and play with friends.3. School eventsSchool events include Seitoku Orientation and Classroom Visitations by Parents and Community Residents, in addition to marathon races and athletic meets. Seitoku Orientation is participated in by all students, and positioned as an activity of the students’ association. Students develop their own original plays using the school grounds, quizzes, and games, and teams of children complete for the highest total score. On Classroom Visitation Day for Community Residents, community residents, along with parents, are allowed to visit the school to view classes and teaching methods.The school holds general classes by utilizing nature, and the basic pillars of these classes are “original and unique approaches to provide opportunities for direct experience and activities” and “support to enhance the strengths of individuals”. More than ten subjects and 73 classes are related to the natural environment on the school grounds. Twenty-six (or the largest number of) classes utilize the farm environment. The farm environment is the topic adopted by eight (or the largest number of) subjects, and provides a variety of values [43]. Sixth graders were asked to draw “a correlation diagram between humans and the environment” to express their views of nature including their experiences of it. This activity was divided into three stages and implemented over a one-year period. Although students only expressed the relationships between humans, plants, and animals in the first stage, they were able to draw pictures of the food chain and water circulation in the second stage. In the third stage, they were also concerned over environmental problems, including air pollution, deterioration of the ozone layer, and deforestation [44]. Students who had undergone this class were aware that they were part of the ecosystem, and concerned over environmental problems. A survey was conducted in which students of third- to sixth-year classes (one class in each school year) wrote a picture diary of the most impressive place in the elementary school. The playground was drawn in 86 of 181 pictures - the largest number, followed by 77 pictures of the natural environment. However, it should be noted that 49 of 50 sixth graders drew the natural environment. Twenty-seven of their pictures were related to subjects from classes held according to the curriculum, such as the strong points of the school, an event involving baking sweet potatoes, and cultivation of potatoes [45]. This reflects that students were proud of their school being surrounded by nature, and that they were familiar with nature.Seitoku Elementary School has provided environmental education not only in social studies and science classes, but also developed it into many other academic curriculums, including art, domestic science, physical education, and home economics, which should be positively evaluated. The school has also adopted unique daily living curriculums to facilitate exchanges between seniors and juniors, and created a friendly atmosphere. As a result, the school as a whole has been promoting effective environmental education. It should also be noted that the school assigns some learning tasks to sixth graders to develop nature-related issues into environmental problems. As a more important challenge, it is necessary to motivate students who have recognized environmental issues as problems to take specific actions.

4.3. Proposition of Environmental Education through Agriculture

- Finally, environmental education through agriculture is proposed in this paragraph, based on the above-mentioned history, data, and examples. As described in [2, 3], environmental education aims to train people who: “consider themselves as part of the ecosystem, view environmental problems as an issue relevant to them, properly understand environmental problems, and voluntarily choose to take actions that are environmentally friendly to solve these problems”.(1) Crops to be cultivated in agricultural fieldsThis paragraph discusses what crops should be produced. I recommend that “sticky rice” should be cultivated when paddy fields are available, and “sweet potatoes” in fields (if available). As these crops can be used for certain activities, such as rice cake pounding and potato baking, schools can organize harvest festivals, inviting parents and community residents, as held in Yanominami Elementary School. If a large area of farmland is available and a variety of crops can be cultivated, crops that reflect the season, including summer and winter vegetables, should be grown, which helps students learn the diversity of organisms and have a better understanding of the ecosystem.(2) Sites for learning agricultureIf farmland is unavailable, agricultural activities cannot be implemented. Where should we then implement them? It is advisable to develop farmland in the school when it has a large area of land. If a school does not have a large space, deserted agricultural fields can be used. Since farmland in Japan is often left uncultivated due to the aging of farmers and labor shortages [46], landlords will also benefit if their fields are cultivated by children. The total area of deserted agricultural fields is 380,000 hectares [47], and the total number of elementary schools in Japan is approximately 22,000 [48]. In other words, at least 16 hectares of farmland are available to all Japanese elementary schools. Since deserted agricultural fields are widely distributed across Japan, as shown in Figure 3, they can easily be accessed by the schools, although their locations should be considered.

| Figure 3. Map of the distribution of deserted agricultural fields in municipalities prepared from the data of MAFF, Japan. [49] |

5. Conclusions

- The present study discussed environmental education through agriculture based on historical documents and data, and the results suggested its effectiveness. The study also suggested that current environmental education through agriculture has some problems. People have not yet integrated environmental actions into their daily habits. If this problem is solved, environmental education through agriculture will be improved.It is not easy to initiate environmental education through agriculture. There are many obstacles to be overcome to initiate this form of environmental education, including collaboration with schools, the community, and society, securing sites for education, and preparation. However, the implementation of environmental education through agriculture is significant. As described in the preceding paragraphs, environmental education aims to train people who: “consider themselves to be part of the ecosystem, view environmental problems as an issue relevant to them, properly understand environmental problems, and voluntarily choose to take actions that are environmentally friendly to solve these problems”. It should be noted that environmental education itself is also an action to solve them. In other words, educators should take the initiative and actions independently. To initiate environmental education, efforts should be exerted to overcome many obstacles.This is the first and most required step to conduct successful environmental education.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML