-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

World Environment

p-ISSN: 2163-1573 e-ISSN: 2163-1581

2014; 4(3): 93-100

doi:10.5923/j.env.20140403.01

Petroleum Pipelines, Spillages and the Environment of the Niger Delta Region of Nigeria

Ogwu Friday Adejoh

Department of Urban and Regional Planning, School of Environmental Sciences, Modibbo Adama University of Technology, PMB 2076, Yola, Adamawa State, Nigeria

Correspondence to: Ogwu Friday Adejoh , Department of Urban and Regional Planning, School of Environmental Sciences, Modibbo Adama University of Technology, PMB 2076, Yola, Adamawa State, Nigeria.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2014 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

As a mode of oil transportation, petroleum pipelines traverse the landscape of Nigeria’s Niger Delta Region and utilize vast tracts of land whose original ecosystem has been altered. Constant oil spills and gas blow-outs from these pipelines constitute health hazards for both the people and the environment. The surface pipelines alter the ecosystem; reduce available land for agriculture and other development and impede free movement of goods and services. Therefore, this paper underscore pipelines as a major infrastructure development that impact adversely on the environment of Nigeria. It analyses the petroleum pipelines and the associated spillages from the perspective of environmental justice. The paper advocates a new approach that promotes inclusion of the necessary stakeholders and would incorporate local knowledge and experience into the environmental management of the region with a view to minimise the impacts of the pipelines on the environment and socio-economic activities of the region.

Keywords: Pipeline, Oil and gas, Nigeria, Physical planner

Cite this paper: Ogwu Friday Adejoh , Petroleum Pipelines, Spillages and the Environment of the Niger Delta Region of Nigeria, World Environment, Vol. 4 No. 3, 2014, pp. 93-100. doi: 10.5923/j.env.20140403.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

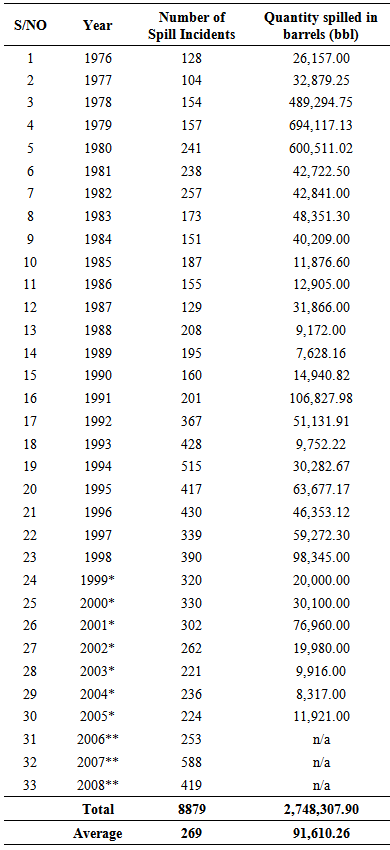

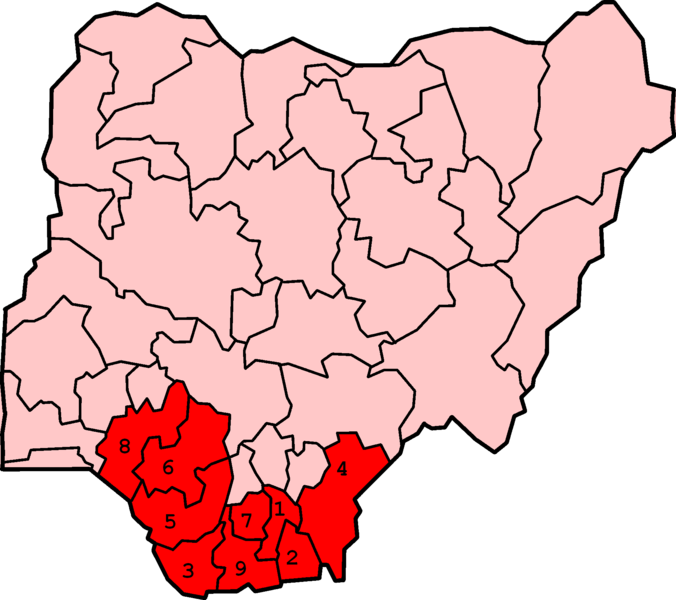

- Nigeria’s economy is dominated by the oil and gas sector. In 2004, this sector accounted for about 80% of all government revenue, 90-95% of export revenues, and over 90% of foreign exchange earnings [1]. The country is Africa’s leading oil producer and at a global level, ranks among the top 10 oil producers [2]. Most of the oil and gas is produced in the Niger Delta Region, presently defined by the political boundary of nine states - Abia, Akwa-Ibom, Bayelsa, Cross-River, Delta, Edo, Imo, Ondo and Rivers (Figure 1). Nigeria’s oil and gas operations comprises of assets and infrastructure including 5,284 oil wells, 10 gas plants, 275 flow stations and 10 export terminals [3]. All of these are connected by a network of pipelines that criss-cross the country. These developments often require a large chunk of the wetland be reclaimed and dredged. Oil and gas production has come at a great environmental cost to about 1,500 communities in the Niger Delta where the Nigerian National Petroleum Corporation (NNPC) oil venture partners operate. The impact has been mostly negative to the local communities. The local communities complain of injustice in the distribution of costs and benefits of oil exploration. It is believed that while local communities directly bear the environmental consequences of oil development, such as loss of biodiversity, other regions of the country bear the benefit. Not until the tragic events of Odi (killing and destruction of the village by the military) and Ogoni (killing of Ken Saro Wiwa) [4], many Nigerians appear unaware of the environmental degradation, pollution and neglect that is faced by the oil producing communities. The same pipelines, that bring oil wealth and supply petroleum product to other region the country is causing untold havoc in the Niger delta. In more recent times, the environment in the Niger Delta has been at the centre of local and international discourse in seminars, conferences and even in the government. The trend has been helped by growing recognition within the international arena that any development that constitute environmental problem is not sustainable. On a national scale, this is buoyed by agitations by indigenes of the Niger delta region who feel cheated. Presently, the environment is on the agenda in different forums ranging from local oil producing communities to states and nations. The environmental impact of the petroleum pipeline network in Nigeria, is one that need to be uppermost in these discussions and physical planners ought to be the professionals at the forefront. Following, the suggestion of [4] that physical planners like geographers should be at the forefront analysing the distribution of externalities benefit (positive) and cost (negative) associated with the production and consumption of public goods, this paper (i) highlights the negative externalities (physical, social and economic) associated with oil and gas pipelines on communities in Nigeria (ii) argue the core role physical planners should play in regulating and monitoring oil pipelines in Nigeria. Therefore, this paper highlight the specific context for physical planning input and the necessity for this in pipeline routes, planning, and monitoring of its impact. The paper suggests areas that need review in existing statutes. It might be important to suggest that one of the key objectives of planning whether in the area of development control, plan preparation or programme implementation is the management of land for the benefit of all. In pipeline activities, this objective ought to be brought to the fore since land is a major source of conflict and litigation between oil companies and host communities. Therefore, policy makers, communities and oil and gas companies need be aware of the potential input of land use planners to the activities of oil companies especially in pipeline route planning, impact assessment and monitoring.

2. Brief Literature Review

2.1. Nigerias Oil and Gas Sector

- Nigeria has proven oil reserves of 22.5 billion barrels that are located mainly within the coastal area of the Niger Delta amongst some two hundred and fifty separate fields. About 200 other fields are known to exist and there have been several deep water discoveries. Reserves of natural gas in Nigeria are estimated to be 124 trillion

in 1999 which represented 2.4% of world reserves [5]. Pipelines are part of the core infrastructure of oil and gas production. They are necessary for the transportation, storage and marketing of natural gas, crude oil, and refined petroleum products. Available data put the nation’s pipeline network at over 3,000 km [2]. Pipelines are used to transport petroleum products from oil refineries and import-receiving jetties to storage depots in Nigeria. In Nigeria, petroleum pipeline traverses the entire country’s geo-political zones ranging from the subsea swamp, rain forest to the savannah grass lands and are exposed to diverse climates and soil conditions with varying consequences which include the leaking and seeping of petroleum products with damaging implications for the communities and the environment [6].According to [7], a petroleum pipeline is an essential mode of transport and is therefore an infrastructure of a highly specialized nature. Unlike other modes of transport such as road, pipelines do not improve access for people in communities through which they pass. Rather, they impose constraints on interactions and when located close to houses, are potentially hazardous to life there.Even when a pipeline is no longer in use, it is left to rust in the open field as the oil companies are not willing to spend money dismantling it. After the construction phase, there is usually no periodic monitoring. Monitoring is an important activity to ensure the integrity of pipelines and safety of people in the vicinity. Whereas oil companies attribute most spills to sabotage, the communities argue it is due to failed pipelines and subsequent leakages [8].

in 1999 which represented 2.4% of world reserves [5]. Pipelines are part of the core infrastructure of oil and gas production. They are necessary for the transportation, storage and marketing of natural gas, crude oil, and refined petroleum products. Available data put the nation’s pipeline network at over 3,000 km [2]. Pipelines are used to transport petroleum products from oil refineries and import-receiving jetties to storage depots in Nigeria. In Nigeria, petroleum pipeline traverses the entire country’s geo-political zones ranging from the subsea swamp, rain forest to the savannah grass lands and are exposed to diverse climates and soil conditions with varying consequences which include the leaking and seeping of petroleum products with damaging implications for the communities and the environment [6].According to [7], a petroleum pipeline is an essential mode of transport and is therefore an infrastructure of a highly specialized nature. Unlike other modes of transport such as road, pipelines do not improve access for people in communities through which they pass. Rather, they impose constraints on interactions and when located close to houses, are potentially hazardous to life there.Even when a pipeline is no longer in use, it is left to rust in the open field as the oil companies are not willing to spend money dismantling it. After the construction phase, there is usually no periodic monitoring. Monitoring is an important activity to ensure the integrity of pipelines and safety of people in the vicinity. Whereas oil companies attribute most spills to sabotage, the communities argue it is due to failed pipelines and subsequent leakages [8]. 2.2. Impacts of Pipeline in Nigeria

- Most of the pipes run across the rivers, creeks, swamps and farmland in the Niger Delta, an environment that is wetland fragile, and highly sensitive to stress [9]. For instance, the Shell Petroleum Development Company’s 95 km trunk line runs from Nembe Creek field to Cawthorne Channel field passing through thirty five communities and traversing sixty rivers and creeks of various sizes along its route. Outside the Niger Delta Region, oil and gas pipelines run to petroleum products storage depots in Aba, Enugu, Gombe, Gusau, Ibadan, Ikorodu, Kaduna, Kano, Lagos, Ilorin, Maiduguri, Markurdi, Ore and Yola, and a refinery at Kaduna. With associated gas gathering programmes at Bonny, Soku and Brass, the pipeline network has increased greatly. The mangroves of the Niger delta also represent one of the most threatened biologically diverse habitats in the world. Hectares of the mangrove in the region have been cleared often without recourse to local environmental legislations or global environmental best practices. This has led to reduction in habitat area and delineation of natural populations, which in turn distorts biological breeding. Apart from wetland reclamation for pipeline construction, leaks from the pipeline as a result failure or sabotage also threaten the environment. Therefore, the unique biodiversity of the region has changed drastically and many important species have been lost [10]. In a recent study, thirty interview respondents with knowledge of the area were asked to state the single most important cause of oil spillage in the Niger Delta. Their response underscores the fact that pipelines are a major source of environmental degradation in Nigeria (see table 2). Specifically, the following are identified environmental impacts a) Destruction of seabed by dredging for pipeline installation:b) Sedimentation along pipeline routes:c) Water pollution from leaking pipes:d) Explosion of pipes resulting from vandalism/ and/ or sabotagee) Destruction of environmentally sensitive estuaries wet landsf) Occasional cause of erosion and floodingg) All of the above have serious effects on the health of humans and animals.

2.3. Distribution of Negative Externalities

- The idea that some actors are winners gaining something and others losers are experiencing costs raises ethical questions which highlight the importance of distributive justice while analysing impacts of projects. Mostly it is the losers that are most vulnerable, conversely the winners tend to be less vulnerable and possess the economic and privileged political power to influence institutions and the decision making process [11]. Dissatisfaction with such situation (the socially unequal distribution of costs and benefits of environmental change) led to the birth of the environmental justice movement [12]; [13]; and [14]. Justice of distribution directly relates to the manner in which the benefits and costs of ecosystem services are shared. Apart from the failings relating to location of pipelines, there is the social aspect dealing with compensations. At its inception in 1977, the Nigerian National Petroleum Corporation paid compensations for portions of land acquired for its projects but with the promulgation of the Land Use Decree of 1978, compensation payment by the Corporation was limited to economic trees and structures. The decree excluded compensation for land acquired for projects such as pipelines. This has been responsible for agitation by host communities, which have often led to vandalising the pipelines and other oil installations [2].

2.4. Existing Regulation

- There are statutory regulations that require a development permit for any new project as well as permit to survey (PTS) a pipeline route be obtained by oil companies from the Department of Petroleum Resources (DPR), in Nigeria. There are also regulations that require an environmental impact assessment (EIA) be carried out prior to approval being obtained for the project and subsequent execution. Pipelines in excess of fifty kilometres require an EIA [3]. Nigeria is also a signatory to international regulations such as Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) and has adopted other documents such as Agenda 21 which has implications on environmental management within the country [7]. However, in spite of its significance, not much has been done by way of enforcing environmental impact assessment of pipelines in Nigeria [6]. Some of these laws have direct bearing on oil pipeline construction. An example is the Oil Pipeline Act of 1956, amended by the Oil Pipeline Act of 1965 drafted into CAP 338 of the Laws of the Federation of Nigeria (LFN). It governs the grant of licences for the establishment and maintenance of pipelines [10]. In addition, [7] observe that the Department of Petroleum Resources specifies under Part VIII Section A 1.4.3 of its guidelines that an Environmental Impact Assessment Report is mandatory for some activities including drilling operations, construction of crude oil production facilities, tank farms and terminal facilities, oil and gas pipelines (in excess of 50km), hydrocarbon processing facilities and production processes. [15] Identify safeguards pertinent to abatement of environmental problems arising from mineral resources exploitation activities in Nigeria and broadly classified these as follows:a) Statutory provisions for prohibiting and controlling the pollution of the environmentb) National policy on the environmentc) Oil spill monitoring programmesThe Mineral Act of 1946 which vested all mineral oils in Nigeria with the government prohibits pollution of the environment through exploration activities and made provision for the restoration of the extraction areas;a) Mineral Oils (safety) Regulations of 1963, which requires oil company operators to meet specified minimum standards of safety;b) Oil in Navigable Waters Regulation, 1967, which controls oil operations in Nigerian Waters;c) Oil in Navigable Water Act No,34 of 1968, which implements Nigeria’s adherence to convention for the prevention of sea pollution;d) Petroleum Regulations, 1967, which prohibits discharge of petroleum into waters;e) Petroleum Decree, 1969, which formalises the regulations dealing with oil operations;f) Petroleum (Drilling and Production) Regulations 1969, which deals with prevention of oil pollution, well-abandonment procedure and conduct of operations;g) Petroleum (Drilling and Production) Amendment Regulation, 1973, which amended the 1969 Regulations; andh) Petroleum Refining Regulations to be observed within the refining industry.Contrary to popular belief, we argue that there is adequate safeguard pertinent to abatement of environmental problems arising from mineral resources exploitation activities in Nigeria. The challenge is rather related to the following a) Weak and conflicting enforcement mechanism;b) Inadequate laws and rules standards and practices;c) Lack of standing to sue for environmental wrong;d) A judiciary sympathetic to oil companies and government interests; e) A biased government; andf) A controversial right to the environment.

3. Overview of Present Scenario

- In order to give an overview of the way physical planning practice can be integrated into the operations of the oil industry in Nigeria; one would need an insight of the prevailing situation at the moment.[10] Submits that for fairly big projects such as the establishment of oil refineries, construction of oil pipelines that run over fifty kilometres, housing estates, etc, the town planning authorities always require the submission of an environmental impact analysis report. He points to the facts that legal provisions for the preparation of environmental impact statements are common to Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) Decree 86 (The Federal Government has the oversight) and the Nigerian Urban and Regional Planning Decree (NURPD) 88 of 1992.This overlap raises some important questions. For instance, can an EIA prepared for the purpose of securing a development permit under section 33 of the Urban and Regional Planning Decree be submitted to Federal Environmental Protection Agency (FEPA) and vice versa? Can a developer submit an EIA to the satisfaction of FEPA commence development without a development permit from the planning authority? Perhaps and may be unfortunately the answers to each of these questions is “No”.Therefore, physical planning issues seem more of local problem and it might be better that each tier of government be allowed to play their respective roles.The analysis above would enable the society at large to have the benefit on merit of the physical planning authority construed in relation to Federal Government approved development project.In an event of serious consequences of petroleum activities, the research stresses the need for agencies, parastatals, and other institutions involved in achieving the goals and objectives of petroleum legislation to see each other operating in synergy with other stake holders and authorities in charge of administering relevant legislation. These other authorities should be allowed to play their roles to enable the society to benefit from their symbiotic relationship.The challenges and constraints that surround the achievement of the above restructuring are varied, complex and often multi-cultural. Hence, there is a need for the collaboration of all stakeholders that could undertake the envisaged critical review of the institutional and human resource capacity of the physical planning department and formulate restructuring road maps.

4. Methodology and Result

4.1. Sources of Data, Method of Data Collection and Data Analysis

- The data collection for this paper took place in three case study areas, and included a total of 6 group discussions, 30 in-depth interviews and 2 workshops. The method of data collection determines the reliability and validity of the result. The major approaches adopted for data collection in this study are group discussion and in-depth interviews with key informants. In addition, field observation and textual analysis were used to supplement the data.

4.2. Group Discussions

- For this paper, the groups were all made up of 6 persons and above. Four group discussions were conducted at the beginning of the fieldwork to provide useful background information on the main impacts of the oil and gas pipelines, and to identify the main oil pipeline stakeholders and their roles regarding the impacts. This also helped to identify the policy actors to be enlisted for in-depth interview.

4.3. In-Depth Interviews

- To balance the information on the issues of oil and gas pipelines under investigation and in addition to the group discussions, 30 in-depth interviews were conducted. For these interviews, five respondents were drawn from each of the following organisations: academia, local residents, government departments concerned with petroleum resources, non-governmental organisations (religious and environmental activist groups), oil companies, and physical planning departments.

4.4. Field Observation and Feedback Workshop

- Two feedback workshops were organised towards the end of the fieldwork. The workshop made it possible to communicate preliminary results to the community in a way that would motivate them to act on and use the information, especially in local decision making. The question and answer time helped in gaining further information, for example, information on pipeline leakages and the compensation paid to the community.

4.5. Result

- A notable environmental effect of oil and gas pipeline activities is that of oil spills. No oil and gas pipeline activity is 100% efficient; even in the most technologically advanced countries; pipeline failure may result in oil spills. According to Ukwe et al. (2006), apart from marine pollution and marine debris, oil spillage caused by human activities poses a great danger to the marine environment of the Niger Delta. As such, it is a matter that requires an urgent attention. Whilst the oil companies did blame the local communities for most of the oil spill incidents in the Niger Delta region, the communities on the other hand have equally attributed oil spill as a major problem caused by the oil companies. When asked, during a group discussion, what might be the likely cause of an oil spill, a resident blamed the oil company before anything else.

5. Discussion

- We suggest that the major problems associated with oil and gas pipeline in Nigeria, relates mainly to location issues (routes); end of life disposal of pipelines (to avoid rust and subsequent seepage into ground water); poor enforcement of laws; distribution of benefit and cost i.e. compensation mechanisms. All these are arenas in which physical planners have being making contributions in many societies. While admitting that physical planners have participated effectively in the socio-economic impact assessment, they argue that there is an increased role for physical planners in oil and gas pipeline operation. They further opined that apart from public consultations, which planners should participate and articulate, they should also be involved in social and economic impact assessments. This is mainly because the entire engineering process in determining the pipeline routes constitutes development in the context of Nigerian planning law.It is the view of [16] that urban and regional planning is a profession that puts the welfare of people on the top of environmental and sustainability agenda. According to him, it takes a holistic and comprehensive view of the environment and has robust methods, techniques and tools for environmental management, which should be applied to the exploration industry in order to achieve sustainable exploration. a) EIA should be submitted for all project;b) There should be public participation;c) Strict environmental standards should be adopted by relevant agencies;d) There should be a re-appraisal of militating legislations; ande) The operation of the oil companies must be brought to internationally acceptable; standards and should be held responsible for environmental degradation – “transfrontier responsibilities” and “polluter pay principle” [17].We identify three specific areas of pipelines operation for the participation of Physical planners. These include pipeline route planning, impact assessment, and monitoring and /or enforcement.

5.1. Route Planning

- Oil and gas pipelines are vital mode for the transportation of petroleum products and are therefore considered part of the nation’s infrastructure of a highly specialized nature. Instead of improving access for people in the communities through which they pass, petroleum pipelines impose constraints on access to water ways and farm lands. In addition, when pipelines are located close to residential areas, they pose hazards to life. Under the Nigerian planning law, engineering work is regarded as “development”, so, pipeline routes come within the remit of the planning control. The physical planners have a role to play to ensure oil and gas pipelines do not cause major adverse impacts on the communities and environment.

5.2. Impact Assessment

- Environmental impact assessment studies normally have a section for the assessment of the socio-economic impacts of any proposed major development. The Nigerian planning laws and the Oil Pipelines Regulations make provisions for EIA reports to accompany proposed major development as a pre-requisite for issuing a development permit. This is however an aspect of oil and gas pipelines operations that physical planners have been playing some part in Nigeria even though the maintaining of the identified impacts is not done by the physical planners. The task is still left for the oil company engineers who alone are unable to handle it effectively.

5.3. Monitoring and Enforcement

- Whenever an EIA report is accepted, the job for the physical planners is not yet over. There is a need to monitor both negative and positive impacts of oil and gas pipelines. Positive impacts such as employment generation could be seen as an integral part of the local and sub-regional economic growth. Its potential might be tapped into planning to sustained local economic development. This paper believes this should be one of the jobs of physical planners. Since most oil companies do sign memoranda of understanding (MOU) with their host communities through a partnership framework, community development plans should be prepared based on the MOU. It is believed that every EIA report contains a section on mitigation measures. Negative impacts need to be mitigated. Local environmental plans, at the very least, could be helpful to articulate the different proposals for mitigating negative impacts. This is a role and the paper sees it as an opportunity for physical planners.

6. Conclusions

- Given the strategic importance of the Niger Delta Area in the socio-economic development of Nigeria, environmental sustainability in this area needs to be viewed with the urgency it deserves. Adequate efforts should be made to attend to her environmental problems. Comprehensive environmental plans that will ensure sustainability of development efforts should be put in place. More importantly, effective implementation of these plans must be practiced. Not surprisingly, the concept of environmental justice is contested and means different things to different people. Whilst procedural justice relates to the fairness in access to democratic decision making by individuals, groups or nations; distributive justice has to do with equality and capability where capability links with fair distribution of environmental benefits and costs among actors. It is distributive justice that directly relates to the manner in which the benefits and costs of ecosystem services are shared. Besides, one dimension of justice reinforces the other. For example, the group that controls decision making process will also be privileged in distribution of benefits. This reinforces the need to involve local people in decision making process which is one of the skills in which physical planners are adequately equipped. The paper suggested an integrated management of the region that will involve all the necessary stakeholders including the physical planners. However, good governance in the interest of the served public is a precursor to meeting the demands of environmental justice even though compensation may remain a crucial issue.

7. Recommendations

- To end unequal environmental protection in the Niger Delta region of Nigeria, the paper believes that the Nigerian government should adopt five principles of environmental justice which should, among other things, include: guaranteeing the right to environmental protection, preventing harm before it occurs, shifting the burden of proof to the polluters, obviating proof of intent to discriminate, and redressing existing inequalities. Firstly, every person living in the Niger Delta region has a right to be protected from negative effects of oil and gas pipelines and the associated environmental degradation. Protecting this right will require not only the enacting a federal environmental protection act but also the enforcement of such act. The act ought to address both the intended and unintended effects of public policies and oil companies’ practices that have a disparate impact on local residents of the Niger Delta.Secondly, Prevention, elimination of the threat before harm occurs, should be the preferred strategy of the government of Nigeria. For example, to solve the oil and gas pipelines spillages problems, the primary focus should be shifted from pollution cleaning as well as treating of water and people who have been poisoned to eliminating the threat by ensuring that oil and gas pipelines are properly buried beneath the earth surface, located far from human settlements as much as possible, and proper and routing maintenance of pipelines by the oil companies.Thirdly, under the Nigerian system, any local individual in the region who challenges polluters (oil companies) must prove that they have been harmed, discriminated against or disproportionately affected. Few poor people in the communities in this region can afford the resources to hire the lawyers, experts and doctors needed to sustain such a challenge. There is the need to shift the burden of proof to the polluters who do harm, discriminate, or do not give equal protection to local poor majority of people living in the region. Environmental justice would require the oil companies that are applying for operating permits for oil and gas pipelines construction to prove that their operations are not harmful to human health, will not disproportionately affect minorities or the poor, and are non-discriminatory.Fourthly, the various laws governing the activities of the oil industries, and those that relate to the oil and gas pipelines in particular, must allow disparate impact as opposed to “intent” to infer discrimination since it is almost, if not altogether, impossible to prove intentional or purposeful discrimination in the Nigerian court of law.Lastly, disproportionate impacts must be redressed by targeting action and resources. By this, the research means that resources should be spent where environmental and other socio-economic problems are greatest, as determine by some ranking scheme (FEPA already has some ranking schemes)– but this should go beyond risk assessment. Relying solely on proof of a cause-and effect relationship could disguise the exploitative way the polluting companies have operated in some oil producing communities in the region. Because it is difficult to establish causation, the polluting companies could continue to have the upper hand. This can make them to always hide behind science and demand proof that oil and gas pipelines activities are harmful to humans or environment of the Niger Delta region.

Appendices

| Figure 1. Map of Nigeria showing the Niger Delta Region in red [21] |

| Figure 2. Erosion exposes Oil pipelines in a community of Okrika [18] |

| Figure 3. Farm land impacted by oil spillage [11] |

| Figure 4. A ruptured oil pipeline burns in 2008 in a Lagos suburb after an explosion which killed at least one hundred people [19] |

|

| Figure 5. Drinking water source impacted by an oil spill from a pipeline [20] |

References

| [1] | Aluko, A.O. (2004) Land Acquisition and Payment of Compensation by the NNPC, Report of the Officers Management Development Programme, Course 038, Asaba. |

| [2] | Olokesusi, F. (2005) Environmental Impact Analysis and the Challenge of Sustainable development in the Oil Producing Communities. Abuja: NITP. |

| [3] | Joab, P. S. (2004) "Transnational Oil Corporations and the Niger Delta Sustainable Development Question". Awka: NIPR. |

| [4] | Human Rights Watch (2000) Impacts and management of oil spill pollution along the Nigerian coastal areas. Administering Marines spaces: International Issues (pp. 119-133). |

| [5] | Handasah, D. (2003) Bonny Master Plan: Final Draft Existing Report. Portharcourt: NITP. |

| [6] | Agbaeze, K.N. (2002) Petroleum Pipeline Leakages in PPMC Report for Chief Officers Mandatory Course 026, Lagos. |

| [7] | Nnah, W.W. and Owei, O.B. (2005) Land Use Management Imperative for Oil and Gas Pipeline Nework in Nigeria. Abuja. |

| [8] | Niger Delta Development Commission (2001) Sustainable Livelihoods and Job Creation, Technical Committee on international conference on development of the Niger Delta, Portharcopurt, Nigeria, December, 2001. |

| [9] | Ogon, P. R. (2006) Oil and Gas: Crises and Controversies 1961-2000. Brentwood: Multi-Science Publishing Co. Ltd. |

| [10] | Olomola, O. A. (2005) Nigerian Environmental Law: A Critical Review of main Principles, Policy and Practice. Enugu: Immaculate Publication. |

| [11] | Ajakaiye, B.A. (2008). “Combating Oil Spill in Nigeria: Primary role and responsibility of the National Oil Spill Detection and Response Agency (NOSDRA)” Stakeholders’ Consultative Workshop. August 4 – 6, 2008, Calabar, Nigeria. |

| [12] | Bullard, R.D. (1994) Environmental Racism and the Environmental Justice movement. Humanities Press, New Jersey. |

| [13] | Pulido, L. (1996) Environmentalism and Economic Justice, USA: University of Arizona Press. |

| [14] | Byrne J., Martinez C., and Glover L. (2002) A brief on Environmental Justice. London: Transaction Publisher. |

| [15] | Sada, P.O. and Odemerho, F.O. (1998) Environmental Issues and Management, Proceedings of the National Seminar on Environmental Issues and Management in Nigerian Development, Ibadan: Evans Press, pp.224 - 229. |

| [16] | John, Y.D. (2007) Post Mining Operation and the Environment, Paper presented at the annual conference of the Nigerian Institute of Town Planners, 31st October to 4th November, 2007, Asaba. |

| [17] | Our Common Future (1987) United Nation World Commission on Environment and Development (WCED), Oxford: Oxford University Press. |

| [18] | Circle of Blue (2009) War on Water: A clash over oil , power and poverty in the Niger Delta, Circle of Blue, September, 2009. Available at : http://www.circles ofblue.org/waternews/2009/world/war-on-water/ |

| [19] | The Observer (2010) Nigeria's agony dwarfs the Gulf Oil Spills. The Observer, 2010. Available athttp://www.gurdian.co.uk/world/2010/may/30/oil-spills-nigeria-niger-delta-shell. |

| [20] | Amnesty International (2009) Catch of the Day: Oil Spill in the Niger Delta Cost Lives, Niger Delta, September 2009. Available at: http://catch of the daynews.blogspot.com/2009/09/oilspills-in-niger-delta-cost-lives-html. |

| [21] | Uyigue, E. and Agho, M. (2007) Coping with Climate Change and Environmental Degradation in the Niger Delta of Southern Nigeria, Community Research and Development Centre (CREDC) Nigeria. |

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML