-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

World Environment

p-ISSN: 2163-1573 e-ISSN: 2163-1581

2012; 2(5): 90-103

doi: 10.5923/j.env.20120205.01

The Immoderate Complexities to Model Government and the Environment

Pedro Erik Carneiro

International Relations, Universidade de Brasília, Brazil, União Educacional de Brasília, Centro Universitário Unieuro, Secretariat of Economic Policy, Brazilian Ministry of Finance. Brasília, 70048-900, Brazil

Correspondence to: Pedro Erik Carneiro , International Relations, Universidade de Brasília, Brazil, União Educacional de Brasília, Centro Universitário Unieuro, Secretariat of Economic Policy, Brazilian Ministry of Finance. Brasília, 70048-900, Brazil.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This paper explores the issues and challenges to model government and the environment variables.[16] did not even conclude on fiscal activism,[20, 21, 22 and 23] did not justify an environmental agreement in their economic models,[28] talks about the unsettled problems related to natural resource. In[1], it is argued that the State is of the utmost importance for environmental management. However, we try to include the government functions in his model to greenhouse gas emissions and found that the cause-relatio n began to deteriorate.[2]´s game, which discusses land reform and deforestation in Brazil, turned government into only a commitment related to only a side of the land conflict. Using their game, we consider REDD’s impact on Brazilian land reform policies. The effect of REDD on the conflict and deforestation will depend on the strength of the governance. Finally, we felt the need to observe environmental public spending. We considered the budgets from Brazil and the UK. The environmental issues still require greater priority, especially in Brazil. The Brazilian federal budget for the environment suffers from volatility and a lack of focus. We observed that despite centuries discussing the government functions and the importance of the environment, the modelling of these two variables still demands the inclusion of government effectiveness, institutions, human nature and uncertainties. Our general conclusion is that the comprehensiveness and effectiveness of government are not properly revealed in the economic models. We argued for a bounded rationality approach.

Keywords: Environmental Public Policies, Economic Modelling, Environmental Public Spending, Bounded Rationality

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Many often say that macro variables are simpler than micro ones because analysts do not have to deal with particularities of consumers, households or firms. It should be better to observe from above, looking the forest not the tree. But, government and the environment, two macro variables, have complexities that have been challenging since the dawn of time of the economic analysis. Regarding government, every civilization in history established a kind of government. As[3] said, the word for governor in the Inca Empire was tukrikuk, “he who sees all”. A contemporary of Plato and Socrates, Xenophon, wrote about economics, exploring the proper organization and administration of private and public affairs, in his book called Oeconomics. In[4] we see that before Plato and Xenophon, chief among Confucius’ precepts were a) government spending should be adjusted to government revenues, not the other way around; and b) government should maintain a general posture of non-interference, yet provide assistance to production and sustain equitable distribution of income when necessary.As[5] observes, some say that the very idea of economics arose from the formation of the nation-state. Most books on the history of economic ideas justly start by saying that the development of the nation-state and the birth of the great monarchies brought about the need to study the state apparatus, also in relations with the other (nation-) states. They therefore, while mentioning the various precursors, introduce the preparatory work in political economy and state theory by Hobbes, Locke, Hume, to then the Physiocrats and the Mercantilists. In a book exclusively dedicated to discuss the fundamentals of the economic role of government, with diverse authors,[6] concluded that these fundamentals are not simple and obvious, the various ideologies, schools of economic and political thought and decision-making techniques are by their very nature limited.As argued in[7], governments are human institutions. It is common, but misleading, to personify “government” and to speak as if some entity has power to act as agency independent of the people who make choices. So, what does explain our tendency to use the government variable as exogenous? With regards to the environment as variable in the economic modelling, first we must say that environmental issues in the realm of economic analysis are not new, quite the opposite. As[8] shows, classical economics began trying to impose limits on growth because of environmental capacity. It held the physical world (particularly land) as the ultimate resource and the foundations of early theories on carrying capacity (Malthus), limits to economic growth (Ricardo), and the steady-state (Mill). The dismal science was born out of a warning about, not a prescription for, unabashed economic growth. With the power of mathematics, the neoclassical revolutionaries Marshall, Walras, and Pigou began a now century-old mechanistic view of social systems with a common denominator of the individual pursuit of utility.Today, we have an enormous amount of literature on the environment and political economy. Only considering the relation between growth and pollution control,[9] argued that the economics literature examining the link between growth and the environment is huge. It covers, in principle, much of the theory of natural resource extraction, a significant body of theory in the 1960s and 1970s on resource depletion and growth; a large literature in the 1990s investigating the implications of endogenous growth theories; and a new and still growing literature created in the last decade examining the relationship between pollution and national income levels. Every review has to make difficult choices about exclusion.Environmental problems reached even the financial market. We can see a lot of indexes related to environment as the Dow Jones Sustainability Index, the FTSE Environmental Opportunities All-Share Index and the Standard and Poor’s Alternative Energy Index. With all this academic tradition discussing government and the environment, one should expect some answers related to how government should spend and tax and if we should worry about the physical world as a limitation to the development. The aim of this paper is to observe why we still have virtually the same questions of our scholars of the past. Confucius’ precepts are still in discussion every day and the limits to growth argued by Malthus and Ricardo are on the agenda today. This paper focuses on the complexities to deal with government and the environment in an economic model.This is a hard task.[9] needs almost 70 pages to develop four simple growth models only to analyse economic growth and one aspect of the environment: industrial pollution. This paper starts outlining the most common complexities surrounding the debate about government and the environment. Then, we analyse two economic models dealing with two environmental problems: greenhouse gas emissions and land conflict and forest degradation in Brazil. After that we discuss two public budgets (from Brazil and the UK). The public budget is an important source for understanding the support to the environment in a country and gives us more proximity to the real world, which frequently we miss when dealing with modelling. As[7] said, economists almost without exception agree on the need for a rule-setting and contract-enforcing agency, but what about the content of rules?

2. Complexities to Model the Government and the Environment

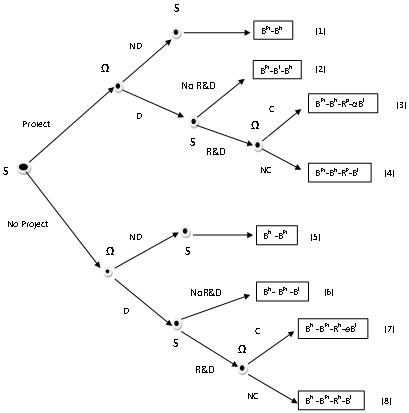

- Some important authors reinforced the difficulties of the mainstream economics to prescribe public policies. In the economic models, we can observe strong divergences among the scholars when discussing government and the environment.For[10], neoclassical theory is simply an inappropriate tool to analyse and prescribe policies that will induce development. He stated that neoclassical theory is concerned with the operation of markets, not with how markets develop. How can one prescribe policies when one doesn’t understand how economies develop? That theory, in the pristine form that gave it mathematical precision and elegance, modelled a frictionless and static world. When applied to economic history and development, it focused in technological development and more recently human capital investments but ignore incentive structure embodied in institutions.[10] highlighted that in the analysis of economic performance through time, neoclassical theory contains two erroneous assumptions: first, that institutions do not matter and, second, that time does not matter.[11] identified other issues in the neoclassical theory. He pointed out that cognitive imperfections, legal rules, culture, habitual behaviour, social norms, available opportunities and information, and past acts of investments and consumption frequently place far-reaching constraints on choices. He argued that modern economics has lost a lot by completely abandoning the classical concern with the effects of the economy on preferences and attitudes.Regarding the government variable,[12] analysed government spending in a model of endogenous growth, but concluded that as is usual in empirical investigation, the hypothesized effects of government policy are easier to assess if the government actions can be treated as exogenous. That is, the results are simple if government randomize their actions and thereby generate useful experimental data. Regularly, as in[13], it is found that the ratio of government consumption to GDP has negative and sometimes significant effect on growth. But, as in[14], it can be concluded that public productive expenditure – capital, transport and communication, health, and education – had either a negative or insignificant relationship with economic growth. The only broad category which is associated with higher economic growth was current expenditure in their model. They argued that developing countries governments have been misallocating public expenditures in favour of capital expenditures at expense of current expenditures, and the developed countries have been doing the reverse. Also in[15], it is concluded that spending on operations and maintenance has a stronger impact on growth than health or education spending. Recently,[16] analysed the fiscal activism of the “great depression” that began in December 2007. Interestingly, their paper has not conclusion, they simply present a final section of discussion. They highlighted several issues that play role in the research on spending and tax. They argued that it is remarkable that, 80 years after the Great Depression of the 30´s and the onset of Keynesian economics, the range of mainstream estimates for multiplier effects related to spending and tax cuts is “embarrassingly” large. They recommended considering behavioral economics. Sometimes, the economic theory focuses on one kind of level of country development to discuss policies. But as in[1], we should consider a wider world, where the government may not be good and may even be bad.[1] focuses on the idea of Kakotopia versus Agathotopia. Agathotopia represents societies in which the government is assumed to maximize social well-being, implementing the best available set of policies. Kakotopia is an imperfect economy, where it is not presumed that the government maximizes on behalf of its citizens, and where agency problems between the government and citizens are possible. In poor countries, where the State is often viewed by communities as an alien fixture and the public realm an unfamiliar social space, the temptation to free-ride on such state benefits as there are, must be particularly strong. Even in “well-ordered” societ free riding would not be uncommon. Living off the State can become a way of life.One relevant quality of public expenditure related to the definitions of Kakotopia and Agathotopia, which is regularly forgotten when modelling due to its intrinsic difficulty, is the cost-effectiveness of the spending. Outcome indicators are not always commensurate with the country’s level of government-financed spending. The service delivery can be inefficient, rather than under-funded. Sometimes, we face duplication and overlapping of public spending, which demonstrate both inefficiency and over-funding with risk of not delivering the service, as in[17]. The Worldwide Governance Indicators (WGI) research project, found in[18], measures six dimensions of governance, one of them is the government effectiveness that measures the perceptions for the quality of public services, the degree of government independence from political pressures, and the credibility of the government's commitment to such policies. However, WGI are based on subjective-based data on governance. The data reflect the views on the governance of the public sector, private sector, NGO experts and thousands of citizen and firm survey respondents. We still need better measures for intangible capital. With regard to the environmental public polices, despite the vast amount of recent literature on the relationship between political economy and the environment, it seems that the majority of academic production has tried to avoid the complexities and focus on the field of pollution control.[9] carried out a review on economic growth and the environment, but they said that it has been a review of work linking industrial pollution and growth with only small asides to consider natural resource use. They sidestepped the issues of property rights protection and the efficiency of environmental policies. They argued that they have done so not because they believe that these issues do not merit attention, but rather because adding a useful discussion of these topics would make that review unwieldy. Also,[19], reviewing environmental law and policy in an economic perspective, focused on pollution control. They said that in an effort to be rigorous in their review while keeping the treatment to reasonable length, they have imposed limits on the scope of their coverage. They focus on pollution control, and do not consider natural resource management, despite the fact that these two areas are closely related. This focus on the pollution control has found power in the international debate on global climate change. The approach is that the countries need to establish an agreement to control the greenhouse gases emissions. In this regard, continuing to discuss the complexities that surround the environment, in the international environmental agreement debate, we have to assume that countries can do better in terms of their own development if they cooperate with each other on environmental issues and then there is an incentive to develop cooperation and institutions. Broadly speaking, it is possible to find equilibrium in the strategies of cooperation between countries if the countries attribute a high value to sustainable development, which means that they use a low discount rate, or if the treaties that establish cooperation change the structure of incentives of the countries.It is regularly assumed, as in[20], that countries can do better when the cooperation between them can be sustained, so they have incentives for developing institutions, which can punish uncooperative countries. The author analyses the power of a self-enforcing international environmental agreement (IEA) to improve substantially upon non-cooperative results. He observes different functional specifications to benefits and costs of the levels of abatement of an environmental pollutant, but in every case the IEAs cannot increase the global net benefits substantially when the number of countries is very large. A self-enforcing IEA only sustains a large number of countries when the difference between the global net benefits under full cooperative and non-cooperative outcomes is small; that is, only when the self-enforcing IEA makes very little effect. To find this result,[20] have to use strong but usual restrictive assumptions in his approach, such as: i) all countries are identical; ii) every country’s net benefit function is known by all countries, and know to be known by all countries, and iii) the abatement levels are instantly and costlessly observable. Recently,[21] observed the literature on IEAs and tried to find optimal behaviour by the IEA to provide a global public good. They changed what they called “the canonical participation game” used to study IEA, and considered mixed and pure strategies. But, they only found that either mixed strategies reinforce the result found with pure strategy, in which the IEA has a lower level of participation, or , with sufficiently low abatement costs, mixed strategy “nearly” solves the free riding problem. In[22], we see a investigation on the formation of binding agreements for providing public goods using the Bargaining Game à la Rubinstein. They focus on coalition formation as a potential source of inefficiency. Their main objective is to establish a complete characterization of the equilibrium coalition structure in a public goods model. While full cooperation is possible, it may not emerge in equilibrium. This means that asymmetric coalitions can exist and provide equilibrium, with the smaller coalition free-riding on the larger one. They use the assumptions of common knowledge, complete information, one pure public good (level of pollution control) and identical members. In[23] the[22]’s result was checked by running an experiment in which the subjects have the chance to sign binding agreements. Their paper provided an empirical analysis to a binding environment agreement. They used the same maximization problem of[22]. The experiment involved 63 participants randomly assigned to a group of seven subjects. Their results show the behavioral aspects of the decisions to form coalitions. The coalitions formed in their experiment present strong differences from those indicated by[22] that considered identical players. In short,[23] shows that: i) players seem to simplify the game choosing singletons or full cooperation; ii) the outcome found in[22] occurred rarely, depending on the treatment (dictatorial or veto); iii) the experimental outcome is, on average, even more inefficient than the theory predicts; and iv) players do not play Nash strategies (using a standard rationality to reach a higher possible payoff given the other players’ strategies). They conclude that different types of behavior co-exist. This means that we face bounded rationality behavior.The importance of using bounded rationality when analyzing environmental policies is very well presented by[24], who shows why the predictions of environmental policies can produce different results if bounded rationality approach is considered. For instance, an anomaly presented by bounded rationality theory is the endowment effect - the disutility of loss of a commodity that is an endowment is greater than the utility of acquiring the same commodity ex-ante. Another important anomaly is the tendency to relate the discount rate to the time horizon. Individuals can reverse their preferences depending on the time horizon.Many times, we observe that the negotiations towards an environmental agreement involve countries with private information about their values (types), sensitivity to the details of the negotiation environment, with limited foresight, and limited iterated reasoning. In that sense, negotiation with environmental agreements should be observed by adding bounded rationality to analytical game theory. Bounded rationality considers restrictions, anomalies, and limits on the decision-making process. As in[25], it can be argued that because we face such uncertainties regarding an environmental agreement, we should have a least human-restrictive approach when analysing such negotiations.[26] also called the attention to the need of historical facts (like political hostilities) in human environmental studies. And[27] pointed out that, to be successful, a global collective action to environmental problems should use legal, policy, institutional and ethical underpinnings, besides good economic theory.Another recurrent issue in the debate on the environment is the called “tragedy of the commons”.[28] argued that the problems of the commons are more important to our lives than a century ago. For him, economic theory has made major contributions to the understanding of commons problems, but these problems have not diminished and the lag between understanding and action can be long. Showing that we are still distant to understanding the tragedy of the commons,[29] develop a model of scarce, renewable resources and found that contrary to the conventional wisdom, property rights defended by economic theorists can often be less efficient than a commons. Regarding the local environmental problems, it is common to use environmental standards to deal with domestic issues. The idea of having standards for environmental problems leads us to the Safe Minimum Standards approach (SMS), defined by[30] as a supplement to the cost-benefit analysis. The SMS places greater emphasis on the protection of the environment wherever the thresholds of irreversible damage are threatened. This approach, notwithstanding, has not met with wide acceptance among environmental economists because, paradoxically, of its strong appeal: uncertainty. To illustrate these, we employ an extensive game, shown in Figure 1.

| Figure 1. Safe Minimum Standards approach (SMS) |

; and3. RP or RN.These three factors, isolated or combined, can change the decisions. Then, they are at the core of the problem. Besides that, the probabilities for each state of nature are extremely relevant for the strategiesAs[31] pointed out, it should be recommended going beyond the probabilities analysis, because not all possible future states of the world may be known, and, even for known states of the world, a mind-boggling list of questions confronts the analyst who would calculate the payoffs for preservation and extinction alternatives. In short, in conclusion to this section, we have seen the possible immoderate complexities surrounding the debate on government and the environment. The modeling of these two variables demands the inclusion of government effectiveness, institutions (legal rules, culture, social norms), human nature (cognitive imperfections, behavior, level of knowledge), frictions of the dynamic world, intertemporal preferences and uncertainty. In the next section, we observe two examples of modeling that, even admitting how important is the government to cope with the environmental problems, failed to include the relevant aspects of the government variable.

; and3. RP or RN.These three factors, isolated or combined, can change the decisions. Then, they are at the core of the problem. Besides that, the probabilities for each state of nature are extremely relevant for the strategiesAs[31] pointed out, it should be recommended going beyond the probabilities analysis, because not all possible future states of the world may be known, and, even for known states of the world, a mind-boggling list of questions confronts the analyst who would calculate the payoffs for preservation and extinction alternatives. In short, in conclusion to this section, we have seen the possible immoderate complexities surrounding the debate on government and the environment. The modeling of these two variables demands the inclusion of government effectiveness, institutions (legal rules, culture, social norms), human nature (cognitive imperfections, behavior, level of knowledge), frictions of the dynamic world, intertemporal preferences and uncertainty. In the next section, we observe two examples of modeling that, even admitting how important is the government to cope with the environmental problems, failed to include the relevant aspects of the government variable. 3. Including Government When Modelling the Environment

- We analysed two models: first, the one found in[1], and then the other found in[2] and[32], enquiring where the variable Government fits into the economic model examining environmental issues.In[1]’s model, we discuss how we can find the government functions in his model. We reinforced the difficulties of establishing a cause-effect relation when trying to incorporate these functions. In the second model, we analyse land reform and deforestation in Brazil. They included government policies in three variables: government will, property rules, and availability of credit. But, the model turned government into only a commitment of someone in power. And this will is related to only a side of the conflict. Using their model, we consider REDD’s impact on Brazilian land reform policies. We concluded that we should expect much more opposition from squatters than from landowners to the adoption of REDD activities. We also found that the effect of REDD on violent conflict and deforestation will depend on the strength of the governance, including environmental public expenditure and monitoring. The two approaches analysed are important in the sense that while[1] in his book “Human Well-Being and the Natural Environment” provides a interesting point of view because of his new concepts to deal with the environment and to evaluate policies,[2] is much more empirical, giving us an idea of how far from reality the economic models are, beginning with the fact a government can have contradictory agencies and laws to deal with the same problem.

3.1. Dasgupta’S Approach

- [1] claims that the State is of the utmost importance for environmental management. Only the State can provide clear property rights and enforce them, assure the communitarian allocation of natural resources, protect and promote investment in the resource base, establish optimal instruments for pollution control (e.g. taxes and cap and trade) and is capable of undertaking infra-structure investment (sewage, rubbish collection). Government spending can provide three strong environmental policy tools: environmental protection, environmental infra- structure and governance. Let us present his approach and relevant arguments.[1] examines quality-of-life measurements as a means of assessing the state of affairs and evaluating policies. He attempts to conciliate methodologies from the economics of environmental and natural resources with development economics. He found it puzzling that no methodology had equated environmental degradation and poverty in poor countries, and that the natural environment is not reflected in the national accounts. In his approach, Nature is considered an array of capital assets (mineral and fossil fuels, soils, fisheries, forest, sources of water, the atmosphere, places of beauty, the oceans, watersheds, etc.); and the way in which Nature and other types of capital (manufacturing, human capital and knowledge) are managed to determine the quality of life. When assessing the state of affairs,[1] uses the concept of accounting prices, which measures the social worth of goods and services. Such prices are dependent upon the property-rights structure and institutional rules pertaining to the allocation of resources. The accounting price of something is the improvement in the quality of life that would be brought about if that thing were costlessly available. His other key concept is the idea of wealth, which, estimated in terms of accounting prices, serves as an index of well-being over time and across generations, and includes all types of capital assets, plus institutions and cultural coordinates. The wealth of an economy is a measure of the social worth of its capital assets. Wealth will change in accordance with what the author calls genuine investment, which is the social worth of the net changes in an economy’s capital assets. Genuine investment must take into account the impact of the current investment practices on environmental resources. This could be negative, even while investment is positive. To evaluate the policies, one should assess whether their investments increase wealth. In the basic model, the economy is closed, the population is constant, the time is continuous and the horizon is infinite. There is only a single consumption good,

, and

, and  denotes a vector of resource flows.[1] gave two examples for

denotes a vector of resource flows.[1] gave two examples for  : rates of extraction of natural resources, and expenditure on education and health. This variable

: rates of extraction of natural resources, and expenditure on education and health. This variable  will be important to our analysis.The economy is given in

will be important to our analysis.The economy is given in  , which is a list of capital assets (including natural capital). Labour is supplied inelastically and normalized as a unity. Current well-being,

, which is a list of capital assets (including natural capital). Labour is supplied inelastically and normalized as a unity. Current well-being,  , is therefore taken to depend on consumption.

, is therefore taken to depend on consumption.  is strictly concave, twice differentiable and monotonically increasing. Given the technological possibilities and resource availability, and the dynamics of the ecological-economic system, decisions made by individual agents and governments from

is strictly concave, twice differentiable and monotonically increasing. Given the technological possibilities and resource availability, and the dynamics of the ecological-economic system, decisions made by individual agents and governments from  onwards will determine

onwards will determine  ,

,  and

and , for

, for  as functions of

as functions of  ,

,  and

and  . The consumption stream, resource flows and capital assets depend on

. The consumption stream, resource flows and capital assets depend on  and

and  . A resource allocation mechanism,

. A resource allocation mechanism,  , maps from capital assets and time to

, maps from capital assets and time to  which is the economic programme (and also economic forecast),

which is the economic programme (and also economic forecast),  with

with  . Social well-being,

. Social well-being,  , can be expressed as a function of the state of the economy at

, can be expressed as a function of the state of the economy at  (

( ) and of resource allocation, as a value function:

) and of resource allocation, as a value function: | (1) |

, as

, as  , is time, and

, is time, and  is the rate of time preference and

is the rate of time preference and  . The accounting price,

. The accounting price,  of capital is defined as:

of capital is defined as: | (2) |

, corresponds to sustainable development at

, corresponds to sustainable development at  if

if  .[1] argues that this concept of sustainability helps us to understand the nature of economic programmes and is useful for evaluating imperfect economies which face technological, ecological, and institutional constraints.Genuine investment is equal to the rate of change in social well-being if

.[1] argues that this concept of sustainability helps us to understand the nature of economic programmes and is useful for evaluating imperfect economies which face technological, ecological, and institutional constraints.Genuine investment is equal to the rate of change in social well-being if  is autonomous (i.e., economic variables at date

is autonomous (i.e., economic variables at date  are a function only of

are a function only of  and

and  ). This implies that genuine investment,

). This implies that genuine investment,  , is:

, is: | (3) |

, is a global common. In which case,

, is a global common. In which case,  is an argument in the value function

is an argument in the value function  of every country.

of every country.  can be an economic good for some countries, while it is bad for others. The value function now for country

can be an economic good for some countries, while it is bad for others. The value function now for country  is:

is: | (4) |

| (5) |

is used as the emission rate from country

is used as the emission rate from country , and

, and  as the rate at which carbon in the atmosphere is sequestered. It thus follows that:

as the rate at which carbon in the atmosphere is sequestered. It thus follows that: | (6) |

| (7) |

and

and  depend on international resource- allocation mechanisms, is introduced under cooperation mechanisms, such as the Kyoto Protocol, and that also has impacts on both accounting prices. Doing that, we are back to the international environmental agreement discussed in the section 2, which led us to the necessity of bounded rationality approach.

depend on international resource- allocation mechanisms, is introduced under cooperation mechanisms, such as the Kyoto Protocol, and that also has impacts on both accounting prices. Doing that, we are back to the international environmental agreement discussed in the section 2, which led us to the necessity of bounded rationality approach. 3.1.1. Including Government

- Now, we discuss the inclusion of the government variable in[1]’s model. First, let us consider where the government variable could be in his approach. The best option is the variable

. This variable contains expenditure on education and health. It is unclear in[1] what kind of expenditure this implies, but we can assume that it is both public and private expenditure. It is also important to say that[1] excludes the impact of on resource allocation

. This variable contains expenditure on education and health. It is unclear in[1] what kind of expenditure this implies, but we can assume that it is both public and private expenditure. It is also important to say that[1] excludes the impact of on resource allocation  . It means that public expenditure or the rate of extraction of natural resources has only an influence on the economic programme

. It means that public expenditure or the rate of extraction of natural resources has only an influence on the economic programme . Moreover, accounting prices and genuine investment only have an impact that derives from capital assets. With respect to the analysis of greenhouse gas emissions,[1] includes the stock of carbon dioxide into the value function in (4), which means the economic programme

. Moreover, accounting prices and genuine investment only have an impact that derives from capital assets. With respect to the analysis of greenhouse gas emissions,[1] includes the stock of carbon dioxide into the value function in (4), which means the economic programme  also has

also has  as its determinant. However,[1] did not explain the relation between the stock of carbon dioxide and the variable that might include government (

as its determinant. However,[1] did not explain the relation between the stock of carbon dioxide and the variable that might include government ( ). We can define the emission rate as a function of renewable energy that is, in turn, a function of private and public expenditure or incentives on renewable energy. Since the rate of extraction of natural resources is included in , the rate of renewable energy in

). We can define the emission rate as a function of renewable energy that is, in turn, a function of private and public expenditure or incentives on renewable energy. Since the rate of extraction of natural resources is included in , the rate of renewable energy in  should be too. Also, the rate at which the carbon in the atmosphere is sequestered should depend on governance.The use of

should be too. Also, the rate at which the carbon in the atmosphere is sequestered should depend on governance.The use of  as a function of

as a function of  can be called into question. The reverse could be more appropriate, i.e., the adoption of (4) without

can be called into question. The reverse could be more appropriate, i.e., the adoption of (4) without  can be contested. Using the model developed by[1] for the global common stock of carbon dioxide, we could change equations (4), (6) and (7) respectively, using

can be contested. Using the model developed by[1] for the global common stock of carbon dioxide, we could change equations (4), (6) and (7) respectively, using  also to represent governance and public expenditure. We should consider another accounting price for

also to represent governance and public expenditure. We should consider another accounting price for  , which we called

, which we called  . Then, we have:

. Then, we have: | (8) |

| (9) |

| (10) |

denotes the function of governance and public expenditure through

denotes the function of governance and public expenditure through  and

and  . Furthermore,

. Furthermore,  retains a direct impact on genuine investment; while

retains a direct impact on genuine investment; while  ,

,  and

and  continue to depend on international resource allocation mechanisms.Government spending should also be included in

continue to depend on international resource allocation mechanisms.Government spending should also be included in  , but[1] should reconsider the definition of

, but[1] should reconsider the definition of  . Summing up, we face difficulties to define the relations of cause in the process of modelling. The government provides property rights, institutions, schooling and planning that have an impact on environmental issues. It is not merely a consumer.

. Summing up, we face difficulties to define the relations of cause in the process of modelling. The government provides property rights, institutions, schooling and planning that have an impact on environmental issues. It is not merely a consumer.3.2. Government, Land Conflict and Deforestation

- In the second model we examine, found in[32], they analysed the access to land in Brazil and its effects on deforestation. The authors considered two groups: landowners and squatters, and two governmental agencies INCRA (the National Institute for Colonization and Agrarian Reform) and IBAMA (the National Institute for Environment and Renewable Resources).The authors point out that, in Brazil, there is inconsistency between the civil law that supports the title held by the landowners, and constitutional law that supports the right of squatters to claim land that is not in “beneficial use”. This institutional failure is a cause of deforestation, and conflict between landowners and squatters, and even extends to disputes between INCRA and IBAMA. The government’s behaviour reflects conflicting goals between INCRA and IBAMA. Let us succinctly examine the problem as posed by the authors. Having invaded a property, squatters seek support from INCRA which has the authority to expropriate private land that is (allegedly) not fulfilling its social function, for purposes of land reform. Landowners can appeal to the courts, by filing for repossession. However, in many cases, they first try to evict squatters using their own means, thereby avoiding costly litigation. The appraisal of the value of the land and improvements is based on price data held by the banks, registered at notary offices, or informed by rural-extension officers and real estate brokers. However, INCRA must comply with the federal public-spending limits, and is thus unable to respond to all squatters’ requests. The authors observe that the selection of land to be expropriated is based on the organized lobbying efforts of squatters and rural workers’ unions, such as the Landless Movement (MST). The leaders of this movement, that celebrated its 25th anniversary in 2009, understand the rules of the game, involving squatters, landowners, INCRA, the federal government, the courts, and the general public (which tends to side with the weaker side, i.e. the poor, long-suffering peasants). The MST knows that violence can draw the attention of INCRA and of public opinion.With respect to deforestation, the relationship between land reform and deforestation in Brazil is quite clear. When landowners perceive that their land runs the risk of being invaded, they have an incentive to replace forest with pasture. Once cleared, their property is less likely to be accused of failing to fulfil its social function, and its commercial value increases. IBAMA reports that the threat of land reform is one of the main drivers of deforestation by landowners. Squatters also have incentives to clear the forest under the current land-reform regime. In order to plant subsistence crops, squatters must clear the area, and sales of valuable lumber help to finance their efforts. Since INCRA’s performance is measured in accordance with how many families it settles on expropriated farms, there is a clear conflict of interest between the two federal agencies (INCRA and IBAMA) and this has a direct impact on the two ministries (Agriculture and Environment). The[32]’s game considers two antagonists (squatters and landowners), the land reform agency (INCRA) and the courts. The objective of both antagonists is to possess ownership of the land. Violent conflict arises from an invasion by squatters and efforts by the landowner to evict them. Squatters do not attempt, independently, to take the land by force or through the courts. Rather, they try to attract INCRA and have the land expropriated. On the other hand, landowners resort to force (issuing threats, hiring gunmen, or calling in the police) or appeal to the courts. The game is used to predict how shifts in the key variables will lead squatters and landowners to change their tactics, and how this affects the likelihood of violent conflict arising. There are three possible outcomes to the conflict: 1) the squatters are evicted and the landowner keeps his land, expressed by the value

; 2) the squatters obtain expropriation, receiving

; 2) the squatters obtain expropriation, receiving  , leaving the landowners with

, leaving the landowners with  (a below market-price for the land) where

(a below market-price for the land) where  ; and 3) there is an unsolved case: the squatters are not evicted, but they do not get expropriation from INCRA. In this case, the squatters receive

; and 3) there is an unsolved case: the squatters are not evicted, but they do not get expropriation from INCRA. In this case, the squatters receive  and the owners obtain

and the owners obtain , where

, where  ,

,  and

and  , since it is considered that the owners prefer an unsolved case to expropriation.Shift in the cost of invasion or eviction (

, since it is considered that the owners prefer an unsolved case to expropriation.Shift in the cost of invasion or eviction ( ) will affect the behavior of the squatters and landowners. Squatters’ cost falls if it becomes easier to influence INCRA. Landowners’ cost depends on the resources to evict squatters. In order to bring all this to bear upon our goal of discussing government variable in models to environmental problems, we refer to[2], in which, using the same game, the authors consider changes in public policy (

) will affect the behavior of the squatters and landowners. Squatters’ cost falls if it becomes easier to influence INCRA. Landowners’ cost depends on the resources to evict squatters. In order to bring all this to bear upon our goal of discussing government variable in models to environmental problems, we refer to[2], in which, using the same game, the authors consider changes in public policy ( ). The probability of INCRA expropriation depends upon three variables: the squatters’ efforts (

). The probability of INCRA expropriation depends upon three variables: the squatters’ efforts ( ); the quality of the property rights of the owner (

); the quality of the property rights of the owner ( ); and the commitment of the government to land reform (

); and the commitment of the government to land reform ( ). The authors, then, included government policies into three variables:

). The authors, then, included government policies into three variables:  for government will,

for government will,  for better rules, and

for better rules, and  for government policy relating to the availability of credit. The model seems to try to avoid the comprehensiveness of the government variable and the potential extent of its impact. But it turned government into only a commitment of someone in power. And this will is related to only a side of the conflict.The authors recognized that government policy can affect several of the variables in the model: changes in the budget for land reform and changes in personal commitment by the President affect

for government policy relating to the availability of credit. The model seems to try to avoid the comprehensiveness of the government variable and the potential extent of its impact. But it turned government into only a commitment of someone in power. And this will is related to only a side of the conflict.The authors recognized that government policy can affect several of the variables in the model: changes in the budget for land reform and changes in personal commitment by the President affect  ; changes in agricultural policy and availability of credit affect

; changes in agricultural policy and availability of credit affect  ; and changes in the rules for land reform and enforcement of property rights can affect

; and changes in the rules for land reform and enforcement of property rights can affect  . However, in their analysis of the game, they adopt the strong assumption that an increase in the level of government political will towards land reform increases the probability of INCRA intervening in the conflict to expropriate the farm. This means that, in this model, the government’s will is related to only one side (squatters), such will is not reflected in the correction of institutional failures or the better application of the rule of law. Thus, in their model, the effect of changes in such governmental policy will lead to more violent conflict. As the government in their models is on the side of the squatters, it has no concern for rule of law that could avoid or reduce the invasions, the probability of expropriation (

. However, in their analysis of the game, they adopt the strong assumption that an increase in the level of government political will towards land reform increases the probability of INCRA intervening in the conflict to expropriate the farm. This means that, in this model, the government’s will is related to only one side (squatters), such will is not reflected in the correction of institutional failures or the better application of the rule of law. Thus, in their model, the effect of changes in such governmental policy will lead to more violent conflict. As the government in their models is on the side of the squatters, it has no concern for rule of law that could avoid or reduce the invasions, the probability of expropriation ( ) has a direct relationship with

) has a direct relationship with  and

and  , and an inverse relationship with

, and an inverse relationship with  .As previously stated, the landowner can use violence (

.As previously stated, the landowner can use violence ( ) or the courts (

) or the courts ( ) to evict squatters. The courts are assumed to be favourable to landowners, and INCRA, to squatters. The probability of the squatters’ eviction (

) to evict squatters. The courts are assumed to be favourable to landowners, and INCRA, to squatters. The probability of the squatters’ eviction ( ) bears a direct relationship to

) bears a direct relationship to  and

and  .In[32], it is argued that they view conflicts over land as a static game, considering property rights, the government, and the courts as exogenous variables. The authors try to assess the odds of violent conflict with changes in

.In[32], it is argued that they view conflicts over land as a static game, considering property rights, the government, and the courts as exogenous variables. The authors try to assess the odds of violent conflict with changes in  ,

,  and

and  . When analyzing the impact of these parameters, the most important factor is the landowner’s private efforts to exert his ownership (threats, hiring gunmen or calling the police). The authors predicted that one should expect more violent conflict with decreases in

. When analyzing the impact of these parameters, the most important factor is the landowner’s private efforts to exert his ownership (threats, hiring gunmen or calling the police). The authors predicted that one should expect more violent conflict with decreases in  and

and  and with increases in

and with increases in  , since such changes induce landowners to step up their private efforts in order to exert their ownership.

, since such changes induce landowners to step up their private efforts in order to exert their ownership. 3.2.1. Including REDD

- Now, we attempt to introduce the concept of REDD into the[32]’s game. The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) defines Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Degradation (REDD) as policy approaches and positive incentives regarding issues relating to reducing emissions from deforestation and forest degradation in developing countries, and the role of conservation, the sustainable management of forests and the enhancement of forest carbon stocks in developing countries. REDD can be an inexpensive approach for reducing greenhouse-gas emissions, as compared, for example, to reducing emissions in the energy sector. However, the lower cost of REDD depends on three factors: 1) opportunity cost; 2) the extent to which REDD is adopted internationally; and, more importantly for our analysis, 3) the capacity of the country to measure and monitor its emissions, avoiding “leakage” (deforestation drops in one area but increases in another) and “non-additionality” (deforestation drops, but not due to REDD). We can view this last factor as a requirement for stronger governance.In observing the land reform problem as presented by[32] in the light of REDD characteristics, two impacts of the adoption of REDD can be foreseen. Certainly, REDD will lead to an increase in the value of land (

), because less land will be available for private production; and REDD will promote stronger property rights (

), because less land will be available for private production; and REDD will promote stronger property rights ( ), in view of the demand for guarantees in order to issue carbon credits. In this game, increases in

), in view of the demand for guarantees in order to issue carbon credits. In this game, increases in and a stronger

and a stronger  have inverse impacts, since these variables have opposite effects on landowners’ private efforts to protect their property rights. It can be expected that a higher

have inverse impacts, since these variables have opposite effects on landowners’ private efforts to protect their property rights. It can be expected that a higher will lead to more violent conflicts and deforestation, whereas a stronger

will lead to more violent conflicts and deforestation, whereas a stronger  will do the opposite. What, then, is missing in our attempt to ascertain how REDD will affect land reform and deforestation? REDD can be achieved through a variety of different activities, such as protecting forests, conservation projects, ecotourism, or confronting the drivers of deforestation. Such drivers could simply be institutional failures. We argue that one should focus on a lack of governance when observing the effects of REDD on land reform.In the case of Brazil, it is not quite accurate to state that the invasion of land is illegal, since constitutional law upholds the right of squatters to claim land that is not in “beneficial use”. Were this not the case, we could regard squatting as illegal, and the probability of expropriation (

will do the opposite. What, then, is missing in our attempt to ascertain how REDD will affect land reform and deforestation? REDD can be achieved through a variety of different activities, such as protecting forests, conservation projects, ecotourism, or confronting the drivers of deforestation. Such drivers could simply be institutional failures. We argue that one should focus on a lack of governance when observing the effects of REDD on land reform.In the case of Brazil, it is not quite accurate to state that the invasion of land is illegal, since constitutional law upholds the right of squatters to claim land that is not in “beneficial use”. Were this not the case, we could regard squatting as illegal, and the probability of expropriation ( ) could be considered the probability of a crime. The land reform policy in Brazil is an example of ill-specified property rights. Institutional failure owing to discrepancies between civil law and constitutional law has an impact on both land reform and deforestation, and also on the adoption of REDD.However, in order to be compliant with the Clean Development Mechanism of the Kyoto Protocol, REDD activities must be validated, monitored, and verified by an independent Designated Operational Entity (DOE), and thus the government will have the incentive to foster better institutional and environmental governance. In the game, REDD must have the same impact as

) could be considered the probability of a crime. The land reform policy in Brazil is an example of ill-specified property rights. Institutional failure owing to discrepancies between civil law and constitutional law has an impact on both land reform and deforestation, and also on the adoption of REDD.However, in order to be compliant with the Clean Development Mechanism of the Kyoto Protocol, REDD activities must be validated, monitored, and verified by an independent Designated Operational Entity (DOE), and thus the government will have the incentive to foster better institutional and environmental governance. In the game, REDD must have the same impact as  ; and INCRA, as a federal agency, must observe REDD criteria when ordering expropriations. The probability of expropriation would also be a function of REDD:

; and INCRA, as a federal agency, must observe REDD criteria when ordering expropriations. The probability of expropriation would also be a function of REDD: | (11) |

What about the effect of REDD on landowners and on the probability of eviction? As previously stated, REDD activities should increase land values, whereas stronger property rights will reduce the landowners’ court costs. Thus, according to the variables of the[32]’s game, we perceive only beneficial effects for landowners. Furthermore, we did not perceive any need to include REDD as a variable in the probability of eviction (

What about the effect of REDD on landowners and on the probability of eviction? As previously stated, REDD activities should increase land values, whereas stronger property rights will reduce the landowners’ court costs. Thus, according to the variables of the[32]’s game, we perceive only beneficial effects for landowners. Furthermore, we did not perceive any need to include REDD as a variable in the probability of eviction ( ) function. The effect of REDD activities on landowners is already present in

) function. The effect of REDD activities on landowners is already present in  and

and  .Thus, our conclusion is that we should expect much more opposition from squatters than from landowners to the deployment of REDD activities. Furthermore, the effect of REDD on violent conflict and on deforestation will still depend on the strength of governance, which includes public spending on the environment and on monitoring. In the next section, we discuss two public expenditures related to the environment, to observe the content of the rule as required by[7].

.Thus, our conclusion is that we should expect much more opposition from squatters than from landowners to the deployment of REDD activities. Furthermore, the effect of REDD on violent conflict and on deforestation will still depend on the strength of governance, which includes public spending on the environment and on monitoring. In the next section, we discuss two public expenditures related to the environment, to observe the content of the rule as required by[7].4. Public Spending on Environmental Protection

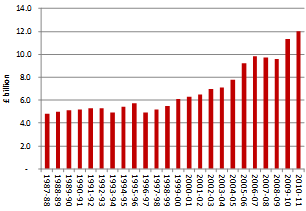

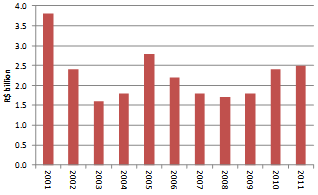

- Nature, as[3] pointed out, is unfair, unequal in its favours. And nature’s unfairness is not easily remedied.[33] argued that despite substantial tecnhnological innovations environmental charcateristics have largely maintained relative influence on land values. Countries have different formal and informal constraints (institutions) that have an impact on the environment. The environmental public expenditure reflects these endowed and forged conditions.Commonly, the countries use the function of Environmental Protection to represent the allocation of resources to environmental services. Environmental Protection can be a pure public good but also a pure private good, depending on the natural asset, the geographical conditions and even the political process. The public expenditure on environmental protection differs greatly among countries, making it almost impossible to establish stylized facts or find answers through econometric tests.[34] tried a cross-country analysis using OECD countries for environmental protection, but found that the overriding conclusion is that the data on environmental expenditure are so poor that it is very much open to question whether econometric exercises are currently worthwhile. Because of the comprehensive aspect of environmental protection, it is difficult to find any papers or articles that deal satisfactorily with the issues related to environmental protection. Concerning OECD countries, as shown in hte Figure 1, public expenditure on environmental protection is the lowest among expenditure by government functions. The environmental protection function usually involves waste management, waste water management, pollution abatement, protection of biodiversity and landscape, R&D related to the environment and environmental protection not elsewhere classified (n.e.c). This function represents only 1.7%, on average of total expenditures, for 31 OECD countries. Japan, Korea and New Zealand stand out having higher environmental protection expenditures over total spending.In this section, we illustrate the difference in public environmental expenditure among countries, using two institutionally and environmentally different countries: the UK and Brazil. Both of these countries, for different reasons, wish to be the leaders in all discussions relating to the environment, including the debates on climate change or energy supplies. The UK and Brazil, like other countries, face environmental issues that threaten their way of life and infrastructure. In the UK, aside from worries about the loss of biodiversity and problems of waste management and water quality, the most pressing concerns relate to flood defences and heat waves. Brazil faces almost the whole spectrum of environmental issues, most notably: deforestation, loss of biodiversity, predatory fishing, soil depletion, devastation of riparian woods and mangroves, the silting up of rivers, water scarcity and drought. We will present the central-government environmental expenditure through the Functions of Government, as this would appear to be the best way to accompany public policies and to make comparisons between the two countries. The UK follows the United Nations’ Classification of the Functions of Government (COFOG) and acknowledges 10 functions: 1) Social Protection; 2) Health; 3) Education; 4) General Public Services; 5) Economic Affairs; 6) Defence; 7) Public Order and Safety; 8) Recreation, Culture and Religion; 9) Housing and Community Amenities; and 10) Environmental Protection.

|

| Chart 1. The UK Expenditure on Environmental Protection, in real terms, 1987-88 to 2010-11. Source:[37] |

|

| Chart 2. Brazil Expenditure on Environmental Management, in real terms. Source:[38] |

|

|

5. Conclusions

- It is not possible to cover all mind-blogging implications of government and the environment and all the spectrum of economic modelling dealing with these variables. No one did that. However, we can argue that despite centuries discussing environmental public policies, Confucius’ precepts are still in discussion every day and the limits to growth argued by Malthus and Ricardo are on the agenda today. Economics, as a discipline, does not develop a straight line including important variables to improve the understanding of government and the environment. The cause for that can be the own immoderate complexities related to government and the environment. The modeling of these two variable demands the inclusion of government effectiveness, institutions (legal rules, culture, social norms), human nature (cognitive imperfections, behavior, level of knowledge), intertemporal preferences and uncertainties.We gave a broad perspective of the weakness of economic modelling when it analyses government functions and highlighted the importance of government effectiveness. Regarding the environment, we discussed the international environmental agreement, the tragedy of commons, and environmental standards, reinforcing mainly the need to include bounded rationality approach and uncertainties when debating environmental issues. We considered two environmental issues, greenhouse gas emissions and deforestation, to present the difficulties to include government when modelling the environment. The two approaches are important because[1] provides new concepts to deal with the environment and to evaluate policies and[2] give us an empirical point of view. In[1]’s model, we discuss the inclusion of the government functions in his model. We observe how confuse the establishing a cause-effect relation is when trying to incorporate these functions. In the second model, found in[2] and[32], it is analysed land reform and deforestation in Brazil. They divided the government policies into three variables: government will, property rules, and availability of credit. The model turned government into only a commitment of someone in power. And this will is related to only a side of the conflict. Using their model, we considered REDD’s impact on Brazilian land reform policies. We concluded that we should expect much more opposition from squatters than from landowners to the adoption of REDD activities. The effect of REDD on violent conflict and deforestation will depend on the strength of the governance, including environmental public expenditure and monitoring. The public budget is an important source for understanding the support to the environment in a country and gives us more proximity to the real world, which frequently we miss when dealing with modelling. We considered two public spending, from Brazil and the UK. We observed that environmental issues still require greater priority, especially in Brazil. The Brazilian federal budget for the environment suffers from volatility and a lack of focus. Then, we reinforce the need to observe the government effectiveness. Our general conclusion is that the comprehensiveness and effectiveness of government are not properly revealed in the economic models that are currently used, especially in imperfect economies where some policies can actually reduce the level of efficiency and equity. Successful social science theories should try to demonstrate the mechanics underlying the endogenous functions of government and the environment. We argued for a bounded rationality approach, as in[16, 24, 25, and 31].The English writer, G.K. Chesterton, said that all science is a sublime detective story. Only it is not set to detect why a man is dead, but the darker secret of why he is alive. Plainly, then, maybe the immoderate complexities to model government and the environment come from the fact that both variables are alive.

References

| [1] | Dasgupta, P. Human Well-Being and the Natural Environment. Oxford University Press. Oxford, 2007. |

| [2] | Alston, Lee J., Libecap, Gary D., Mueller, Bernardo. A Model of Rural Conflict: Violence and Land Reform in Brazil. Environment and Development Economics, 4: 135-160, 1999. |

| [3] | Landes, David S. The Wealth and Poverty of Nations. W.W. Norton & Company, New York, 1999. |

| [4] | Ekelund, Robert B. & Hébert, Robert F. A History of Economic Theory and Method. Fifth Edition. Waveland Press, Inc. Long Grove, Illinois, 2007. |

| [5] | Micocci, Andrea. The Philosphy of Economics. In Future of Economic Science, edited by K. Puttaswamaiah. Isle Publishing Company, Enfield New Hampshire, USA, 2009. |

| [6] | Samuels, Warren J. Diverse Approaches to the Economic Role of Government. In Fundamentals of the Economic Role of Government. Warren Samuels, ed. Greenwood Press, 1989. |

| [7] | Harriss, C. Lowell. True Fundamentals of the Economic Role of Government. In Fundamentals of the Economic Role of Government. Warren Samuels, ed. Greenwood Press,1989 |

| [8] | Erickson, Jon D. The Future of Economics in the Century of Environment. . In Future of Economic Science, edited by K. Puttaswamaiah. Isle Publishing Company, Enfield New Hampshire, USA, 2009. |

| [9] | Brock, William A. & Taylor, M. Scott. Economic Growth and the Environment: a Review of Theory and Empirics. National Bureau of Economic Research. Cambridge, MA. Working Paper 10854. October, 2004. |

| [10] | North, Douglass C. Epilogue: Economic Performance Trough Time. In Emprirical Studies in Institutional Change edited by Lee J. Alston, Thráinn Eggertsson and Douglass C. North. Cambridge University Press, 1996. |

| [11] | Becker, G.S. Accounting for Tastes. Harvard University Press, 1996 |

| [12] | Barro, Robert J. Government Spending in a Simple Model of Endogenous Growth. Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 98, No. 5, Part 2: The Problem of Development: A Conference of the Institute for the Study of Free Enterprise Systems (Oct., 1990), pp. S103 -S125, 1990. |

| [13] | Barro, Robert J. & Sala-i-Martin, Xavier. Economic Growth. 2nd Edition. MIT, 2004 |

| [14] | Devarajan, S., Swarrop, V. and Zou, H. The composition of public expenditure and economic growth. Journal of Monetary Economics, 37, 313-344, 1996. |

| [15] | Glosh, S. and Glegoriou, A. The composition of government spending and growth: is current or capital spending better? Oxford Economic Papers, v.60, 484-516, 2008. |

| [16] | Auerbach, Alan J., Gale, William G. and Harris, Benjamin H.. Activist Fiscal Policy. Journal of Economic Perspectives: Volume 24, Issue 4, Fall 2010. |

| [17] | US Government Accountability Office. Opportunities to Reduce Duplication, Overlap and Fragmentation, Achieve Savings, and Enhance Revenue. 2012. Available at http://www.gao.gov/products/GAO-12-342SP, accessed on 10 March 2012. |

| [18] | Kaufmann, Daniel, Kraay, Aart and Mastruzzi, Massimo. The Worldwide Governance Indicators (WGI) project, 1996-2010. World Bank, 2011. |

| [19] | Revesz, Richard L & Stavins, Robert. Environmental Law and Policy. Working Paper 13575. National Bureau of Economic Reserach. Cambridge, MA, November, 2007. |

| [20] | Barrett, S. Self-Enforcing International Environmental Agreements. Oxford Economic Papers 46, 878-894, 1994. |

| [21] | Hong, Fuhai and Karp, Larry. International environmental agreements with mixed strategies and investment. Journal of Public Economics, In Press, Accepted Manuscript, May 2012 |

| [22] | Ray, Debraj & Vohra, Rajiv. Coalitional Power of Public Goods. Journal of Political Economy, 109,6, December, pp. 1355-1384, 2001. |

| [23] | Thoron, Sylvie. Sol, Emmanuel and Willinger, Marc. Do binding agreements solve the social dilemma? Journal of Public Economics, Volume 93, Issues 11-12, December, pp 1271-1282, 2009. |

| [24] | Venkatachalam, L. Behavioral Economics for Environmental Policy. Ecological Economics, Volume 67, pp. 640-645, 2008. |

| [25] | Carneiro, Pedro E. A Least Human-Restrictive GATT Environmental Model at the G20. Donetsk National Technical University. Economics. Issue 40-3, pp 186-196, November, 2011. |

| [26] | Varga, Csaba. Environmental Injustices in Central and Eastern Europe: The Minority Pitfall. World Environment, 2(3): 35-37, 2012. |

| [27] | Esty, Daniel C. Rethinking Global Environmental Governance to Deal with Climate Change: The Multiple Logics of Global Collective Action. American Economic Review: Volume 98, Issue 2, May 2008. |

| [28] | Stavins, Robert N. The Problem of the Commons: Still Unsettled after 100 Years. American Economic Review: Volume 101, Issue 1, February 2011. |

| [29] | McAfee, R. Preston and Miller, Alan D. The tradeoff of the commons. Journal of Public Economics, Volume 96, Issues 3–4, ,p. 349-353, April 2012. |

| [30] | Crowards, Tom M. Safe Minimum Standards: The Costs and Opportunities. Ecological Economics, Volume 25, Issue 3, pp-303-314, 1998. |

| [31] | Bishop, Richard C. & Scott, A. The Safe Minimum Standard of Conservation and Environmental Economics. Aestimum 37: 11-40, 1999. |

| [32] | Alston, Lee J., Libecap, Gary D., Mueller, Bernardo. Land Reform Policies, the Sources of Violent Conflict, and Implications for Deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon. Journal of Environmental Economics and Management, 39, 162-188, 2000. |

| [33] | Hornbeck, Richard. Nature versus Nurture: The Environment's Persistent Influence through the Modernization of American Agriculture. American Economic Review: Volume 102, Issue 3, May 2012. |

| [34] | Pearce, David & Palmer, Charles. Public and Private Spending for Environmental Protection: A Cross-Country Policy Analysis. Fiscal Studies, vol.22, no.4, pp. 403-456, 2001. |

| [35] | OECD. Government at a Glance 2011. OECD, August, (2011). Available at http:// www.oecd-ilibrary.org/content/ book/gov_glance-2011-en?contentType=&itemId=/content/chapter/gov_glance-2011-11-en&containerItemId = / content/ serial/22214399&accessItemIds=/content/ book/gov_ glance -2011-en&mimeType=text/html, accessed on 20 February 2012. |

| [36] | OECD. Stat Extracts. 2011 Available at http://stats. oecd. org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=SNA_TABLE11, accessed on 12 March 2012. |

| [37] | HM Treasury. Public Expenditure Statistical Analyses. July, 2011. |

| [38] | National Treasury Secretariat. Relatório Resumido da Execução Orçamentária do Governo Federal e Outros Demonstrativos. Brasília: Ministério da Fazenda, 2011. Available at http://www.tesouro.fazenda.gov.br/contabilidade_governamental/relatorio_resumido.asp, accessed on 20 March 2012. |

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-Text HTML

Full-Text HTML