-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Education

p-ISSN: 2162-9463 e-ISSN: 2162-8467

2026; 16(1): 1-6

doi:10.5923/j.edu.20261601.01

Received: Oct. 3, 2025; Accepted: Nov. 2, 2025; Published: Jan. 28, 2026

Exploring the Growing Reliance on Private Coaching: Insights from Grade 6 Learners at a Girls' School in Bangladesh

Muhammed Amir Uddin1, Tomalika Barua2, Sayema Akther3, Ponika Nath3, Sazneen Sumiya3

1Associate Professor, Institute of Education and Research, University of Chittagong, Chattogram, Bangladesh

2Lecturer, Institute of Education and Research, University of Chittagong, Chattogram, Bangladesh

34th Year Student, Institute of Education and Research, University of Chittagong, Chattogram, Bangladesh

Correspondence to: Muhammed Amir Uddin, Associate Professor, Institute of Education and Research, University of Chittagong, Chattogram, Bangladesh.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Education in Bangladesh has become an adventure these days. Private coaching seems to be the latest national hobby – and everyone is looking for the most popular teacher, as if they are in the Hunger Games for education. You enter into Grade 6, at the Bangladesh Mahila Samity Girls' High School and College (the one you probably have heard of in Chattogram), and it seems to be *the same as always* – national curriculum, rules [lists], etc. But as soon as the final bell rings, boom – they are out of the school, racing off to education's equivalent to a bat cave to visit their coaching session. Parents are living a life based on stress and gossip from a WhatsApp group about which teacher is the education expert. Teachers are shading each other — or at least I think that is what they are doing — with knowing glances. Spending quality educational hours in an environment like this has become ridiculous. No one really knows what is going on – we are just pooling along and hoping for the best! This study looks into reasons of this reliance, examines students' perceptions of coaching versus school teaching, and examines its impact on academic performance, well-being, and social equity. A mixed method approach (surveys, questionnaires, or interviews with students and parents) indicates that students attend coaching to cope with academic pressure, inadequate personalized attention in class and family pressures. Coaching does help students gain clarity and improves performance, yet it comes at a cost of overwhelming academic pressure, less leisure time and emotional stress.

Keywords: Private coaching, Dependence on tutoring, School vs coaching, Academic performance

Cite this paper: Muhammed Amir Uddin, Tomalika Barua, Sayema Akther, Ponika Nath, Sazneen Sumiya, Exploring the Growing Reliance on Private Coaching: Insights from Grade 6 Learners at a Girls' School in Bangladesh, Education, Vol. 16 No. 1, 2026, pp. 1-6. doi: 10.5923/j.edu.20261601.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Private means "personal" and coaching is the work or act of a teacher who gives private lessons to prepare students for examinations' [1] Private coaching is one kind of teaching system where students are given lesson with a financial exchange. It is taught either in a student's house or teacher's house or in a centre. In Bangladesh, the use of private coaching as an after-school academic support system has become so widespread that it is also common among students of class six. Though it was initially meant to assist weak students, coaching has now become the go-to solution of all the learners irrespective of their performance levels due to the academic pressures, competitive environments, and limitations in school-based instruction. Among other things, private coaching will be the vehicle through which individual students will receive their personalized attention, will help through examinations, and will give them the necessary psychological support, especially, in the so-called difficult areas. It also allows students to practice through what they have been taught in school. On the other hand, there are some significant disadvantages. High-pressure issues, less time for relaxing, families facing money issues due to paying for coaches, and getting more and more reliant on help from outside are among the negative impacts raised by private coaching. The students need to be careful because if they lose their motivation, they will hardly want to be engaged in school lessons and this will weaken the whole system of formal education. The purpose of this study is to investigate how Grade 6 students view their dependence on private coaching, including the advantages they experience, the difficulties they encounter, and how it affects their academic career.

2. Objectives of the Study

- Why students go for private coaching — is it because of weak school teaching, exam stress, or pressure from parents? This research strives to extensively examine the academic dependency on private coaching for Grade 6 students in Bangladesh, with the following aims: Whether students join coaching by choice or because they feel they have no option.a) Whether or not students opt for coaching voluntarily or because they think that they have no choice.b) To what extent coaching supports them in exams, in clarifying doubts, or in confidence building.c) Whether or not students feel more encouraged and equipped after coaching than from school classes.d) What kind of problems they face, like stress, having less time for themselves, or lack of interest in school?e) Whether coaching places extra financial burden on families and makes students unequal.f) Where do the students feel more productive to study — coaching or school.g) How important is family income and background in being able to access coaching.h) What should schools do to strengthen teaching so that students will not be forced to rely on coaching.

3. The Cultural Context of Coaching

- The Cultural Context of Coaching in Bangladesh, the education sector of schools is becoming more and more competitive every year. Great emphasis is being given to the success of students at board exams and entry tests for higher studies. Placing a child in a competitive environment, parents find themselves under a tremendous amount of pressure to make sure that their children excel academically. One such measure parents are taking is that they are putting their children into private tutoring which is becoming quite the fad. Private tuition takes one of the best forms that is best suited to fill up the existing gaps between the subjects taught in the schools and the complexities of the examination system. At Mahila Samity Girls' High School & College, Bangladesh, i.e., where students belong to the different socio-economic groups, private tuition is even more important. Although other families might be able to pay for and access the best quality tuition, others will use the cheaper option so that educational assistance is unequal.

4. Merits and Demerits of Private Coaching

- a) At school, students hardly ever receive the attention they need. Coaching provides more personalized attention. Grade 6 students do have a load of schoolwork, though. Their learning and the hours they have to spend with their Coach get incorporated in such a manner that hardly any time is left for the students to play or indulge in leisure activities.b) Coaching involves question pattern, mock tests, and score increase techniques. But then some students get disconnected from school if they can learn the subject more effectively at coaching centres.c) Certain students gain confidence only after receiving additional coaching particularly in such challenging subjects as mathematics and English. Contrary to this, this method suppresses imagination among students.d) Where intelligent schools fall short of teaching effectiveness, coaching may fill the gap to a great extent. Conversely, excessive academic focus may reduce free time which is inevitable for a child's improved development. Moreover, most of the families cannot afford coaching which creates disparities in academic achievement and future opportunities. e) Parents believe coaching ensures their child is being guided outside school hours. But some coaching centers operate as businesses, prioritizing fees over actual educational value.

5. Literature Review

- Review Private tutoring, or "shadow education," is a general phenomenon throughout the entire world which is surprisingly more widespread in the South Asian countries of Bangladesh, India, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka. The term is applied to the paid instruction that is ongoing outside of the school system, typically the same subjects as school. Shadow education has increasingly become a part of the normal academic life of students over the last decades. Various studies have established that students, as well as parents, view private coaching not just as an add-on but as a requirement to achieve academic success. The major explanation is the feeling or reality of the deficits of the traditional education system, i.e., massive class sizes, lack of personalized attention, use of outdated pedagogical methods, and ineffective teacher training [2]. Ahamed et al. [3] indicated that the appearance of private tutoring in countries such as Bangladesh is correlated with the fierce competition of the learning culture and the high-stakes pressure of exams. According to Rahman et al. [4] “Education allows individuals to develop within their community and country and allows nations to compete and survive in the global economy”. Since school grades tend to be the determining factor for children's professional and educational life, parents feel obligated to invest money in private tutoring so that their children will enjoy a better position. This pressure is particularly felt in urban Bangladesh. The trend begins as early as primary school, and students are now relying more and more on tutors, an aspect that is defining the education culture and altering the way students achieve academic excellence. The biggest problem with private coaching is that it affects students' participation in school. Many learners report paying less attention in class because they expect to receive more thorough explanations during coaching sessions. This undermines the central role of formal schooling.Additionally, there are instances where the teachers run private classes after school hours, and in some situations, they even do it with their own students. Burch [5] pointed out this situation as one of multiple conflicts of interest that could result in ethical issues in terms of justice and quality concerning the education in schools. Pupils who are not willing or able to go to such extra classes might be left behind unfairly.A major issue also lies in the inequality fostered by private coaching. According to Dang and Rogers [6], wealthy students are more likely to benefit from good private tutoring and thereby access quality and well-structured private coaching services, while students from low-income families face the challenge of not having enough money to participate. As a consequence, this issue can deepen the already existing ranges of social and academic disparities that, in turn, cause an unequal distribution of educational opportunities and outcomes.Still, private coaching, in any case, not only negatively impacts the social and academic background of students, but also issues of an opposite nature. Zhang [7] acknowledged that the tutors could prepare the students to comprehend thoroughly the subjects, particularly if students are actually weak in the regular teaching methods, only by morally and rightfully conducting the work. Those who want to learn at their own pace, get more practice, and receive more precise feedback than the school system allows can find private tutoring a good opportunity to achieve this.Nevertheless, there is a long debate among educators and policymakers whether the benefits outweigh the losses in the sense of the long-term consequences of overdependence on private coaching. The opponents claim that it leads to the removal of intrinsic motivation in learners, as it encourages the repetition of rote memorization, and the overexertion of attention on examinations at the cost of the comprehensive maturation of education. Additionally, the issue of the commercialization of education through private tutoring becomes a matter that causes concern about how education can be accessible to all, fair in terms of equality, and for what purpose should it be learnt.In conclusion, the study offers a complex and nuanced view of private tutoring. Even though it addresses the issue of inadequacy in the formal education system, it also gives rise to new problems like educational inequality, ethical dilemmas, and the potential transition from meaningful to surface learning. Any future educational reforms must take such a complicated view of the issue into account and find a balance that will be able to make institutional improvements and at the same time respond to supplementary learning demands.

6. Methodology

- The research paper utilized a mixed-methods approach, integrating the qualitative and quantitative data for the purposes of understanding the dependence of Grade 6 students on private tutoring. A questionnaire was utilized in the data collection process. The questionnaire contained both open-ended and closed-ended questions.

6.1. Sample and Participants

- The research was conducted at a selected urban school, with a sample of 25 students from Grade 6 and parents of those students.

6.2. Data Collection Methods

- Two primary tools were used:a) Structured Questionnaires for students, focusing on their preferences, understanding, and experiences in school vs. private coaching.b) Students answered a short survey about where they feel they learn better: school or private coaching.c) Parents were surveyed using semi-structured interviews to delve into their insights concerning learning outcomes, money spent, and the usefulness of tutoring.d) Integrated views of parents on children’s learning through coaching and associated expenditure were explored through interviewing parents.

6.3. Data Analysis

- Quantitative replies were represented with the help of elementary statistics (for instance, percentage, frequency). Besides, thematic analysis was used to examine qualitative data from interviews to uncover common themes and insights.

6.4. Findings and Analysis

7. Perspectives of Students and Teachers

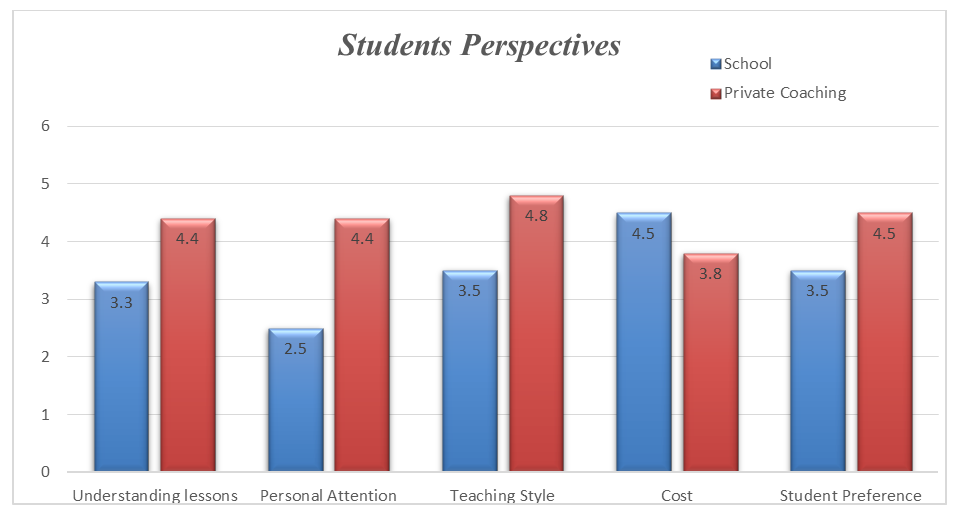

7.1. Students Perspectives

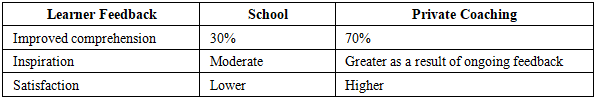

- a) Understanding- 70% of students reported they understand lessons better when in a coaching session with a private tutor. b) Engagement- Several students cited the classes at school as boring, with coaching centre’s more active, interactive, and provided practice.c) Subject Support- Students indicated that coaching offered more exam-centric materials, high-quality practice materials with support.d) What Students Said: About 70% of students said they understand lessons better in coaching classes. Many felt that coaching gives more attention and better explanations. Some said school lessons are fast or hard to follow.

7.2. Parental Perspectives

- a) Perception of Schools: 80% of parents expressed that schools are unable to provide individual attention due to large class sizes.b) Cost vs. Outcome: Private tuition was an additional expense for the family (on average from 1,500 to 3,000 BDT per month per subject), but the majority of parents they agreed that the best academic results were the outcomes of such investments.c) Pressure and Balance: A number of parents that were worried about the combined influence of school and lessons on their children's psyche, nevertheless, they considered that it was important for their children to be able to maintain their position among the academically competitive peers.d) Most parents think coaching helps improve exam results.e) Even though it is expensive, the parents feel that coaching is worth the money. f) Several parents pointed out that their children feel pressured due to coaching, yet they consider it necessary.

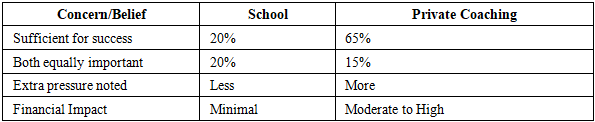

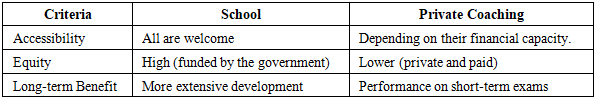

8. Comparative Analysis: School vs. Private Coaching

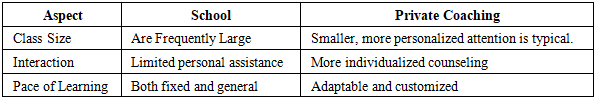

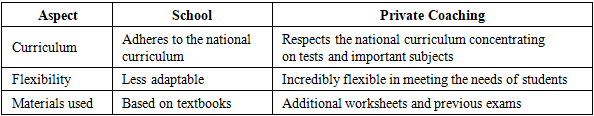

8.1. Learning Environment

- Smaller class sizes and more individualized attention make coaching more engaging and easier for students to follow.

|

8.2. Teaching Approach

- Coaching centers are frequently portrayed as exam-focused businesses. Schools, on the other hand, offer a more comprehensive approach.

|

8.3. Learning Outcomes (Based on Perception)

- The majority of students believe that coaching classes help them learn and retain more information than traditional classroom settings.

|

8.4. Parental Perceptions

- Parents acknowledge the benefits of coaching, but many are worried about the increased expenses and stress.

|

8.5. Overall Balance

|

9. Discussion

- This study backs up what earlier research found about shadow education in South Asia, especially in Bangladesh. Like Bray [8] and Nath [3] pointed out, students really lean toward private coaching. It’s not just a passing trend—big class sizes and a lack of personal attention in regular schools push them that way. Students see coaching as a place where things actually make sense, and the focus on exams is a huge draw. Rahman et al. [4] noticed the same thing: private tutoring isn’t just a bonus anymore, but something families feel they need.If you look at this through human capital theory, it all makes sense. Families want the best returns on education, so they put extra time and money into coaching. Still, equity theory comes into play too—who gets to join these coaching classes depends a lot on how much money their family has, so the gap between rich and poor grows wider [6].There’s also this obsession with exam scores. Coaching centers feed into that, which lines up with criticism of education that’s all about tests. It can kill real curiosity and deeper learning. Burch [5] called out similar problems: when schools and coaching centers run side by side, schools can lose their grip and their impact fades. So, private coaching fills in where schools fall short, but if it keeps growing, it points to bigger issues in the system that need to be fixed.

10. Conclusions

- The study shows that private coaching is now a big part of school life for Grade 6 students in Bangladesh. It definitely helps kids understand their lessons better, score higher on exams, and feel more confident. But when students rely too much on coaching, things get messy. They feel more pressure, start disconnecting from what’s happening in school, and the gap between rich and poor kids just gets wider. So, what can we do?For schools: Try to keep class sizes small so teachers can give students more personal attention. Set up extra support and enrichment programs for kids who learn at different paces. And don’t wait to spot problems—regular feedback and early assessments help catch learning gaps before they get big.For teachers: Focus on student-centered teaching and mix up your methods to reach everyone. Encourage kids to ask questions and get involved in class. The more active the classroom, the less students will feel they need outside help. And keep learning new ways to teach—professional development focused on inclusion and engagement makes a real difference.For policymakers: Set clear rules for private coaching to make sure it’s ethical and high-quality. Put money into teacher training, better classroom materials, and systems that keep everything on track. And run campaigns that remind parents and students there’s more to learning than just chasing grades—well-being matters too.At the end of the day, private coaching should just give students an extra boost—not replace good schools and teaching. If we want kids to rely less on shadow education, we need to make sure regular schools work for everyone. That’s how we close gaps and lower the pressure.

11. Limitations and Future Research

- This study is exploratory in nature and is subject to certain limitations. The sample size of 25 scholars from a single civic girls’ academy limits the generalizability of the findings. Data were primarily grounded on tone- reported comprehensions, which may be told by particular bias. also, the study didn't include direct classroom compliances or academic performance records.Unborn exploration could involve larger and further different samples across pastoral and civic surrounds, incorporate longitudinal designs to examine long- term goods of private coaching, and include preceptors’ perspectives and objective academic issues. relative studies across academy types and regions would further enrich understanding of the shadow education miracle.

Conflicts of Interest

- No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

About the Author(s)

- Muhammed Amir Uddin is an associate professor and specialist in philosophy of education, working in the Institute of Education and Research at the Faculty of Education at University of Chittagong, Bangladesh. He is the author of several works and publications in this field, including on topics such as moral and value education.Tomalika Barua is a Lecturer in the Institute of Education and Research at the Faculty of Education at University of Chittagong, Bangladesh. Her research focuses on inclusive education, shadow education, e-learning systems, and the pedagogical use of digital tools in classrooms.Sayema Akther is a 4th Year Student in the Institute of Education and Research at the Faculty of Education at University of Chittagong, Bangladesh.Pomika Nath is a 4th year student in the Institute of Education and Research at the Faculty of Education at University of Chittagong, Bangladesh.Sazneen Sumiya is a 4th year student in the Institute of Education and Research at the Faculty of Education at University of Chittagong, Bangladesh.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML