-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Education

p-ISSN: 2162-9463 e-ISSN: 2162-8467

2025; 15(2): 19-25

doi:10.5923/j.edu.20251502.01

Received: Oct. 1, 2025; Accepted: Oct. 23, 2025; Published: Nov. 7, 2025

Comparison of Online and Hybrid Teaching Modalities at an Urban Community College Based on Student Experiences

Canan Karaalioglu, Nipa Deora

Department of Science, CUNY, Borough of Manhattan Community College, New York, NY, USA

Correspondence to: Canan Karaalioglu, Department of Science, CUNY, Borough of Manhattan Community College, New York, NY, USA.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

In this paper, we explore the advantages and disadvantages of online versus in-person learning from the perspective of students at Borough of Manhattan Community College (BMCC), a community college within the City University of New York (CUNY) system. As a designated minority serving institution, BMCC serves a student body that comes from a wide range of cultural, socioeconomic, and educational backgrounds. Many of these students are non-traditional learners; most of them are employed part-time or full-time and have family responsibilities along with long and unpredictable commute times mainly using public transport. These factors play a significant role in their educational choices and learning preferences. This paper focuses on the experiences of students enrolled in online or hybrid chemistry and physics courses at BMCC, examining how these learning formats impact their academic engagement, accessibility, and overall satisfaction. Through this analysis, we seek to better understand the specific needs of community college students and how schools can better support them.

Keywords: Online teaching modality, Hybrid teaching modality, Community college students’ responses to different teaching modalities

Cite this paper: Canan Karaalioglu, Nipa Deora, Comparison of Online and Hybrid Teaching Modalities at an Urban Community College Based on Student Experiences, Education, Vol. 15 No. 2, 2025, pp. 19-25. doi: 10.5923/j.edu.20251502.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- The advancement of online learning represents one of the most significant shifts in modern education. In recent years, there has been a substantial evolution in the different learning modules available for college students. Traditional in-person learning which was once the only practical option available to students is currently being supplemented or even replaced by online education resources. Advances in technology have enabled educational institutions to offer more online course options, presenting an effective alternative to the traditional classroom setting.While online course options have been available for several years, the COVID-19 pandemic led to a dramatic increase in the number of available online course offerings and the number of teaching faculty that have been trained to teach online classes [1-5]. On the other hand, this has also further sparked the ongoing debate about which method is more effective in the overall understanding of the course material [6-9]. Banks et al. conducted one of the earliest studies following the COVID-19 pandemic. Data was collected from students who took online classes in Spring 2020 and found that students showed a stronger preference for in-person instruction over online learning [1]. Jaggars (2021) proposed that online learning should be systematically integrated and institutionalized across higher education to ensure preparedness for potential future pandemics or other unforeseen disruptions [2]. Even before the COVID-19 pandemic, Faulconer et al. (2018) conducted a study examining general measures of student outcomes such as grades and withdrawal rates in introductory-level chemistry laboratories. Their findings revealed no significant differences between instructional modalities, leading them to conclude that further research was needed [6]. Seven years later today, the question remains unresolved, and a definitive answer has yet to emerge. In a similar comparison, both Nennig et al. [7], who conducted a pre-COVID study with students enrolled in an introductory-level inorganic chemistry course, and Rowe et al. [8], who examined a biochemistry laboratory course, found no significant differences in student outcomes between instructional modalities. Indeed, Zheng et al.’s study with dental students demonstrated that online learning during the pandemic could produce learning outcomes comparable to, or even better than, those achieved through face-to-face instruction before the pandemic [9].Online learning generally offers more flexibility and accessibility [10,11], making it ideal for students with work or family commitments or those with long commute times. Most community college students balance full time or part time jobs along with family responsibilities [3]. Online learning can provide them with an alternative that can accommodate their needs. As stated by Harris and Martin [10], virtual learning environments provide the students with the needed flexibility to manage their time effectively, enabling them to pursue academic goals without sacrificing other priorities. Even though there are many advantages of remote learning, the authors of this study are also aware online classes are not a perfect solution for all learners. As reported by Lomellini’s study, even though online classes offer more accessibility to disabled students, the design aspect of these courses is lacking in some cases [12]. In another study by Vaillancourt et al., the participants were elementary and high-school students. Even though some still reported they could focus better because of lack of bullying, lack of peer pressure, and lack of social anxiety, the students who opted for remote learning also reported they felt they mattered less [5].In contrast to online learning, in-person instruction provides more opportunities for direct interaction and richer social experiences. It includes increased face-to-face engagement between students and faculty, which can directly contribute to student achievement. The structured environment of an in-person course helps students remain focused and accountable. Even though a comparable structure can be built in an online format, regular in-person meetings with instructors and peers still offer a more consistent routine that supports many students’ stay on track and succeed [1,13]. Additionally, access to campus based resources such as libraries, student organizations, and tutoring centers enhances their overall educational experience. It should be noted that these facilities are also available to students enrolled in online courses who are able to commute to campus. However, their integration into daily academic life is more seamless and frequent for those who attend in-person classes.This paper examines the advantages and disadvantages of online and in-person learning from the perspective of students at the Borough of Manhattan Community College (BMCC), an urban institution within the City University of New York (CUNY) system. BMCC currently offers hundreds of online courses and provides 22 fully online degree programs. However, fully online options are generally unavailable for science majors because of the hands-on nature of laboratories. While some fully online science course options are available for non-science majors, science-related majors typically have access to hybrid courses that combine online lecture with in-person laboratory instruction.BMCC is a minority-serving, urban commuter campus, where most of the students do not live on or near campus. Instead, these students commute to college from various neighborhoods across New York City’s five boroughs, often relying on public transportation. Extended commute times cause significant challenges for many students, particularly in relation to financial burden, family obligations, and work schedules. These factors can negatively affect attendance, participation, and overall academic performance. In this study, we examine the advantages and disadvantages of online learning from the perspective of students. All these students are enrolled in online and hybrid chemistry and physics courses for science majors and non-majors during the Spring 2025 semester at BMCC. By focusing on science courses that traditionally rely on in-person instruction, this research seeks to understand how online learning formats influence academic accessibility, participation, and satisfaction among commuter students.

2. Methods

- Surveys can serve as an important tool for educators to collect data and assess various aspects of the learning experience. We followed the guidelines outlined in the review papers by Hill et al. and Hochberg et al. when designing our survey, including the use of positively worded questions and items with specific response options rather than general statements [14,15]. Our study was initiated by designing a student survey aimed at exploring various factors that impact different aspects of students’ academic and personal lives. The survey included questions related to student commute times, course format availability, and perceptions of the advantages and disadvantages of online learning. The scope of our survey did not include the instructional and interpersonal challenges described in Li et al.’s paper [16]. A total of 62 students participated, all of them were enrolled in one of five sections of online or hybrid science courses: online-only PHY 110 (O), hybrid PHY 110 (H), hybrid PHY 220 (H), and online-only CHE 108 (O). In the hybrid sections, students attended in-person sessions only for the laboratory component, while the lecture portion was delivered fully online. For the online lecture component, participants were enrolled in a combination of synchronous and asynchronous course formats. The responses collected through this survey will be analyzed in the following sections of this paper. The data obtained will be used to evaluate how course formats affect students’ overall educational experience.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Online and In-person Course Options

- The survey began by gathering data on the range of course formats available to students at the time of enrollment and which instructional options they chose to enroll in. Students were asked to indicate their current mode of instruction by selecting from one of the following options: fully online, hybrid, or a combination of in-person and hybrid courses. Fully online classes were defined as the ones that met exclusively online. They were delivered either synchronously (with regular scheduled meeting times) or asynchronously (allowing students to work on their course material at their own pace without regular scheduled online meeting times). Students could also be enrolled in the ‘hybrid’ format which combined both online and in person components. In the hybrid format, students met in person with their instructors and classmates during laboratory meetings. and completed the rest of the course work online. The last category included students enrolled in both in-person and online courses concurrently. This question was designed to provide an understanding of students’ exposure to different teaching modalities.The survey results reveal that a significant number of our students (70%) who had the option to enroll in either in-person or online courses chose online classes. This preference suggests a significant inclination towards online learning programs which can be attributed to various factors which will be analyzed in this study. These results indicate that students’ preference for the hybrid modality has not changed substantially since the pandemic, even though it was initially assumed that students chose this format primarily out of necessity during that period [17].

3.2. Commute Times

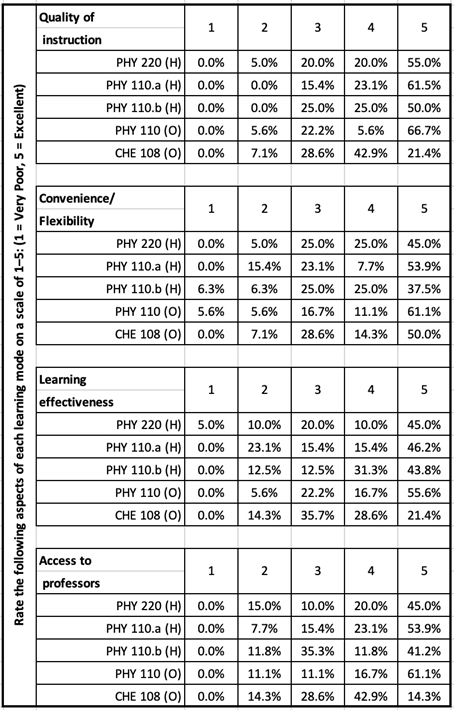

- Commute time is one of the key factors for a student’s well-being. As illustrated in Simone et al.’s paper, even the mode of commute such as driving, walking, cycling, or using public transportation can influence university students’ well-being [18] and, consequently, their academic success. According to their findings, public transportation was identified as the least appealing and least preferred mode of commute. At urban campuses like BMCC, where most students use public transportation, commute times can be substantial and costly, presenting significant challenges for many of the students. These commutes often impose financial burdens and create personal scheduling conflicts. Given that a large portion of the student population is employed either full-time or part-time, a time-consuming commute to campus can be a significant burden. The subject of commute times among CUNY students was previously examined by Regalado et al. in their 2014 study [19], which found that students typically faced one-way commute times of 45 to 60 minutes when using public transportation. Given BMCC’s location within the CUNY system and its predominantly commuter-student population, these findings remain highly relevant. Our own recent survey of BMCC students supports these earlier results where 42% of participants reported commute times between 30 and 60 minutes, while 48% reported commuting for more than an hour. Only 9.8% of students reported that their commute took less than 30 minutes which would be expected for a location in a city like Manhattan (Figure 1).

| Figure 1. Average Commute Times for Our Students. Data Shown as Percentage of Total Survey Responses |

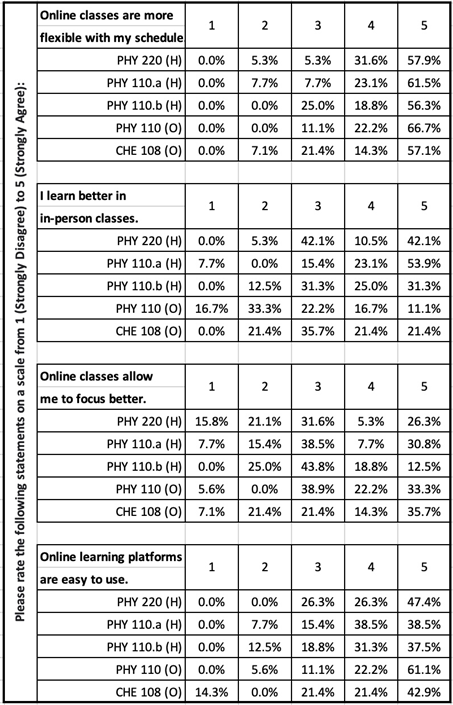

3.3. Overall Student Experience

- The next section of our survey examined students’ experience with online classes with questions addressing instructional quality, convenience, and flexibility of their courses (Table 1). The first question asked students to rate the quality of instruction in their online courses on a scale from 1 (lowest) to 5 (highest). Nearly 50% of respondents rated the instructional quality as a 5, and approximately 74% rated it as 4 or 5. These results suggest a high level of satisfaction with the quality of instruction in the online learning environment. This satisfaction was observed through both the online and hybrid course formats (Table 1).

|

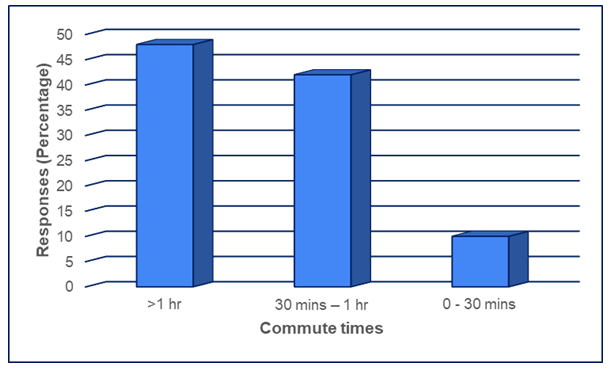

3.4. Technology

- Another important aspect of online learning that has considerably evolved over the years is access to available technology. Digital inequality can be categorized into disparities related to physical access to the Internet, the skills required to use it effectively, and an individual’s ability to translate Internet access into beneficial offline outcomes, as described by Li et al. [16] Moreover, digital inequality can negatively affect students’ learning experiences, particularly within online teaching modalities. Therefore, reliable access to technology and internet connectivity is a key component of digital equity, and is essential for students to succeed in online learning environments. In recent years, technology and internet availability have both improved significantly. This was reflected in our survey data, where the participants reported minimal technical issues while taking the online classes, indicating that the platforms and tools used were reliable and easy to navigate.At BMCC, online courses are administered through the Brightspace learning management system (LMS) which serves as the main hub for course content and faculty-student communication. Many instructors also enhance their courses by integrating additional platforms such as Pearson MyLab [21] and McGraw Hill Connect [22] with Brightspace. These additional platforms are used for assignments, quizzes, and exams, which helps increase student engagement. As part of the survey, students were asked about the ease of using these digital platforms especially in the context of online and hybrid courses. A significant majority (over 73%) rated their experience as a 4 or 5, suggesting that the current platforms are functioning effectively to support online instruction. This indicates generally positive feedback of the technological infrastructure supporting online learning at BMCC. To help promote digital equity, BMCC also provides on-campus computer labs and loaner laptops for students who may lack reliable internet or personal devices at home.

3.5. Flexibility with Schedule

- To better understand how course format options align with the needs of our students, participants were asked how online classes fit with their overall schedules and whether they found them to be more flexible compared to in-person classes. Over 80% of participants rated this question with a 4 or 5, indicating a clear preference for the online courses. (Table 2)

|

3.6. Benefits and Challenges

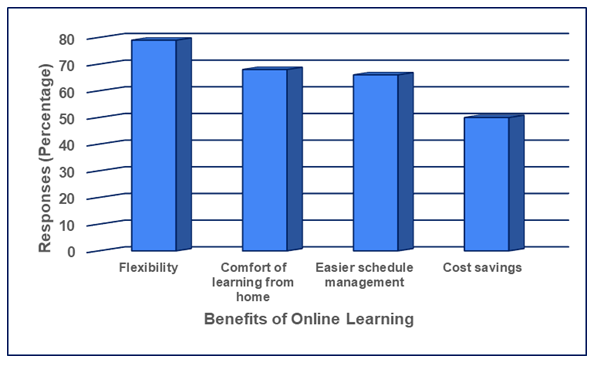

- Students were asked to identify the benefits they experienced with online learning, with the option to select multiple responses. The available choices were flexibility, cost savings, comfort of studying from home, easier schedule management or none (Figure 2). As expected, flexibility was ranked as the greatest benefit, with 79% of the students listing it as a key advantage. This was followed closely by the comfort of learning from home at 68% and easier schedule management, chosen by 66% of the students. Additionally, 50% of the students indicated cost savings as a noteworthy benefit, clearly highlighting how the cost of public transport and commuting in New York City can add up.

| Figure 2. Student responses to benefits of online learning. Data shown as percentage of total survey responses |

4. Conclusions

- In conclusion, the survey results reveal an overall preference among some BMCC students for online and hybrid learning formats, primarily due to the flexibility and convenience these modalities provide as has been observed in similar studies [23,24]. Johnson et al. summarized various aspects of U.S. faculty and administrators’ experiences and approaches during the early weeks of the COVID-19 pandemic [24]. Data were collected through surveys conducted between April 6 and 19, 2020. Although the paper focused on the initial challenges of transitioning to online instruction, it also anticipated the lasting impact of these changes on the future of education and the reduced reliance on solely face-to-face teaching modalities. Today, we continue to discuss the benefits of online and hybrid teaching models while acknowledging that no single approach is ideal for all learners or institutions.For a student population that often balances regular work, family commitments and long commute times, having an online option can offer a significant advantage. Without access to these learning options, many students are forced to reduce their course loads each semester, and extend their time to graduation, potentially delaying their program graduations. Online and hybrid formats empower these students to stay on track towards their academic goals, reducing barriers which could otherwise delay or prevent completion of their programs.While some of our students have shown a clear preference for online and hybrid learning, our data also confirms that this preference is not universal, and in-person learning remains important to many students, similar to Corvin’s et.al. findings [26]. The advantages of traditional in-person learning are well established [12,25] and highlight the importance of face-to-face interaction with faculty and peers. This set up is even more important for students who focus better in a more interactive setting. These findings highlight the continued importance of offering traditional classroom options, especially for students who benefit from in-person engagement and personal connection in their educational experience.At urban commuter colleges like BMCC, it is crucial to recognize that no single instructional format meets the needs of all students. Instead, a flexible, student-centered approach that offers a combination of online, hybrid, and in-person options might best serve the college’s diverse student body. This approach aligns with the constructivist learning theory, which emphasizes that learners actively construct their knowledge through personal experience, reflection and social interaction [10]. Online courses support constructivist learning theory as they promote self-paced reflective learning where students can connect new concepts to their existing knowledge base. In person classes, on the other hand, provide opportunities for enhanced social interaction and collaborative problem-solving. Hybrid models offer a combination of flexibility and interactive learning. As this study highlights, the ability to choose between online and in-person formats plays a significant role in helping students to manage their time, reduce stress, and ultimately succeed in their academic goals. Moving forward, it would be helpful for instructional designers to enhance digital platforms by making them more interactive and providing real-time active feedback. While some of these platforms are already available from commercial publishers, many remain cost prohibitive for low income students. Institutional investment in these technologies could significantly improve access and equity in learning. Supplementing in-person classes with these online resources could provide students with a more flexible and personalized learning experience. Regularly collecting student feedback on course experiences and preferred learning formats can drive continuous improvement in teaching strategies. Furthermore, institutions should offer regular workshops for instructors to ensure that they remain proficient in the latest digital teaching technologies. Lastly, while this study provides valuable insights into the experiences of students at a large, urban community college, there are a few limitations to consider. The data collected is from a single institution and the sample size, though sufficient for exploratory analysis, was modest. A larger sample across multiple institutions would enhance the generalizability of the results and offer a more comprehensive understanding of student preferences. Despite these limitations, this study provides meaningful student perspectives on instructional format choices within an urban community college context.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML