-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Education

p-ISSN: 2162-9463 e-ISSN: 2162-8467

2022; 12(1): 7-15

doi:10.5923/j.edu.20221201.02

Received: Dec. 6, 2021; Accepted: Jan. 21, 2022; Published: Jul. 27, 2022

Intention of Including Learners with Disabilities in Practical Physical Education Lessons by University Teacher Trainees in Ghana

Regina Akuffo Darko1, Jane Mwangi2, Lucy-Joy Wachira2

1Department of Health, Physical Education, Recreation and Sports, University of Education, Winneba, Ghana

2Department of Physical Education, Exercise and Sports Science, Kenyatta University, Nairobi, Kenya

Correspondence to: Regina Akuffo Darko, Department of Health, Physical Education, Recreation and Sports, University of Education, Winneba, Ghana.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2022 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

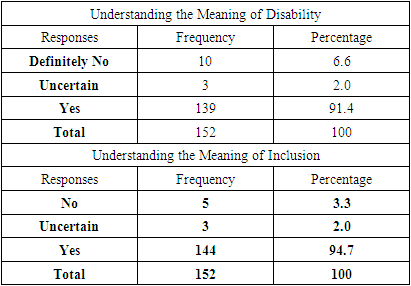

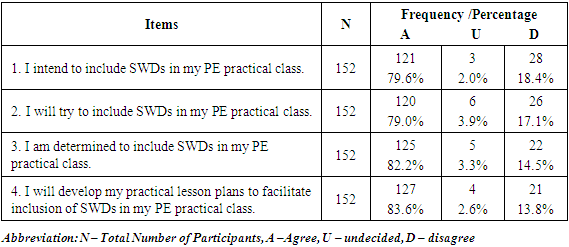

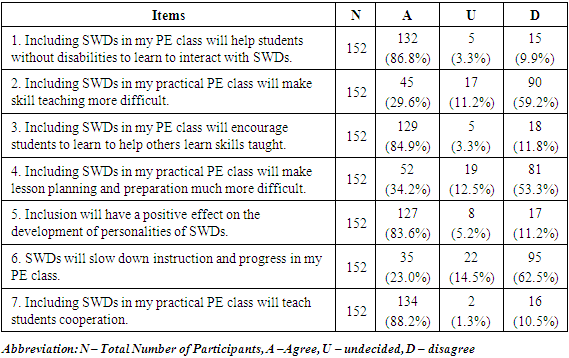

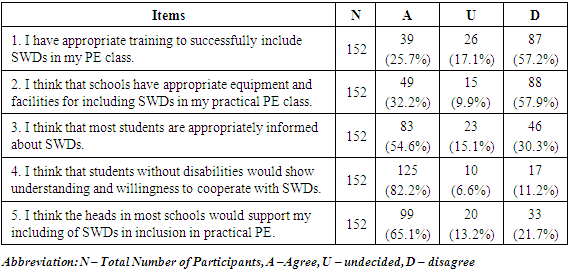

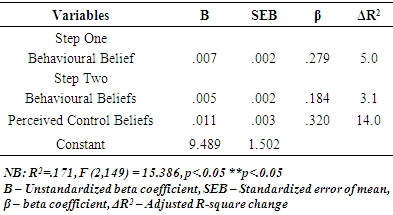

This study aimed at determining PE student-teachers’ intention of including SWDs in practical PE lessons in Ghana. The study involved student-teachers from two universities that train physical education teachers in Ghana. The study used sequential mixed-method design with a sample of 152 level 300 student-teachers selected using the purposive sampling technique. Student-teachers’ intentions, outcome of intention (behavioural beliefs and perceived control beliefs) as well as predictors of intention to include SWDs were ascertained using the Attitude towards Teaching Individuals with Physical Disabilities in Physical Education (ATIPDPE) instrument. The results indicated that student-teachers’ intention to include SWDs was positive however they had anticipated fear rooted from the inadequacy of their training programme and perceived fear of lack of support in terms of equipment and facilities for effective inclusion. Hierarchical multiple regression analysis indicated that perceived behavioural control belief predicted 14.0% of variance in intention than behavioural beliefs did. This study concludes that student-teachers have positive intention to include SWDs in their PE practical lessons. It is recommended that university coursework in Adapted Physical Education and Special Education should be modelled in line with inclusion principles and practices to help student-teachers to frequently reflect on their beliefs and intentions of teaching SWDs in practical PE lessons.

Keywords: Behavioural beliefs, Inclusion, Intention, Perceive control beliefs, Physical education, Students with disabilities

Cite this paper: Regina Akuffo Darko, Jane Mwangi, Lucy-Joy Wachira, Intention of Including Learners with Disabilities in Practical Physical Education Lessons by University Teacher Trainees in Ghana, Education, Vol. 12 No. 1, 2022, pp. 7-15. doi: 10.5923/j.edu.20221201.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Inclusion of students with disabilities (SWDs) in teaching and learning is the new normal. However, intention to include SWDs depends on the teachers views and opinions in relation to their capabilities and abilities to handle inclusive classes based on the preparatory programme they experienced during their training in the University. Inclusion, according to Block (2016) [1] is the instruction of learners with and without disabilities together in regular class with appropriate support and accommodations. Rusanescu, et al. (2018) [2] defined inclusive physical education (PE) as a procedural orientation aimed at unifying the learning process with diverse groups, which include students with and without disabilities in the PE class. Klein and Hollingshead (2015) [3] identified multiple benefits of inclusive PE as increasing blood flow to the brain, increasing intellectual attentiveness, sustaining a positive attitude, and averting illness. Tovin (2013) [4] also stated that inclusive PE lessens hostility, self-stimulatory behaviours and upsurges physical fitness. All these benefits can be effectively achieved through methodological guidelines, attitudes and intentions of the teaching staff and stakeholders involved in the educational process that favour inclusion of SWDs (Bota et al., 2017) [5]. Intention has been defined as the amount of effort a person is determined and willing to exert to achieve a set goal (Ajzen, 1991) [6]. Again, intention denotes the behavioural plans that enable the attainment of behavioural goals (Ajzen, 1996) [7]. According to theory of planned behaviour (Ajzen, 1991) [6], a person’s actual behaviour could be predicted based on the individual’s intentions to perform the behaviour. For instance, whether a PE teacher will include an SWD in his or her practical lessons depends on the teacher’s intention either to include the learner or not. Intentions to perform a behaviour in turn are influenced by three closely related psychosocial paradigms of attitudes, perceived competence, and subjective norms. Attitudes toward the behaviour relate to the person seeing the behaviour positively or adversely. Perceived competence relates to the individual’s capacity to perform the behaviour. Thus, perceived behavioural control denotes an individual’s perception of the effortlessness or difficulty of executing the behaviour of interest, which is partly dependent upon available opportunities and resources for the person to implement the act (Ajzen, 1991) [6]. Subjective norm refers to how significant people in the environment appraise the behaviour. Given satisfactory control over a behaviour, individuals are likely to put into action their intentions when given the opportunities to do so (teacher modifies the game to include an SWD). Thus, it is theorised that intentions capture the motivational factors that impact a behaviour; they are signs of how determined people are eager to try (Ajzen, 1991) [6]. This intent to exhibit a specific behaviour assumes that the behaviour in question is under voluntary control (a teacher has the will, competences, decision-making power, resources and support to effectively include SWDs in motor activities). Considering the application of this theory to the field of inclusive practical PE, suggests that if a student-teacher has a favourable attitude towards inclusion, has competent to include SWDs based on training received as well as believes that school heads will favour inclusion, then the teacher is likely to have positive intentions to include SWDs in their practical lessons. Positive intentions, in turn, would positively shape the teacher’s behaviour and they would most likely include SWDs in their lessons. Currently, the education sector globally is shifting towards inclusive approaches to mitigate limitations witnessed in specialised schools in Ghana thus, advocating inclusive approaches to maximise the benefits of inclusive PE teaching. Obrunsnikova (2008) [8] discovered that the intentions and beliefs of physical educators become more positive as the quality of experience in handling SWDs improves. Beamer and Yun (2014) [9] also reiterated that PE teachers’ self-efficacy is associated with their beliefs regarding teaching SWDs in their general PE classes. Nevertheless, Chicon, et al. (2011) [10] described a situation in which SWDs were left out from general practical PE lessons and had to practice different activities without any clear educational meaning. It is, therefore, imperative that student-teachers require the right attitude and intention to implement the pedagogical and adaptation skills gained in their training to successfully conduct practical PE lessons in an inclusive setting. According to Rust and Sinelnikov (2010) [11] modules in Adapted Physical Education (APE) have shown to develop student-teachers’ attitudes and intention towards teaching SWDs. The authors indicate that well-structured coursework and experiences play an essential part in breeding favourable attitudes and intentions of PE student-teachers towards working with SWDs.However, it is recognised that changes in the organization of initial and continuing education, and a better school administrative structure, can be factors that may contribute to the development of teachers’ positive attitudes and intentions (Taliaferro et al., 2015 [12]; Salerno, & Araújo, 2016) [13]. Therefore, it is necessary to determine the intentions of level 300 university student-teachers who are done with their 3 years on-campus coursework and are about to go out on internship towards inclusion in practical PE in an inclusive setting. Objective of the StudyThe objective of this study was to determine the PE student-teachers’ intentions about including SWDs in practical PE lessons in the two universities (University of Education, Winneba-UEW and University of Cape Coast-UCC) in Ghana. The study aimed at determining the intention of PE student-teachers towards inclusive practical PE lessons, the student-teachers’ behavioural beliefs and perceived behavioural control beliefs towards inclusive practical PE lessons as well as determining the variables that predicts intention. A null hypothesis which stated that behavioural beliefs and perceived control beliefs will not predict the intention of student-teachers to include SWDs in practical PE lessons was also tested.

2. Methodology

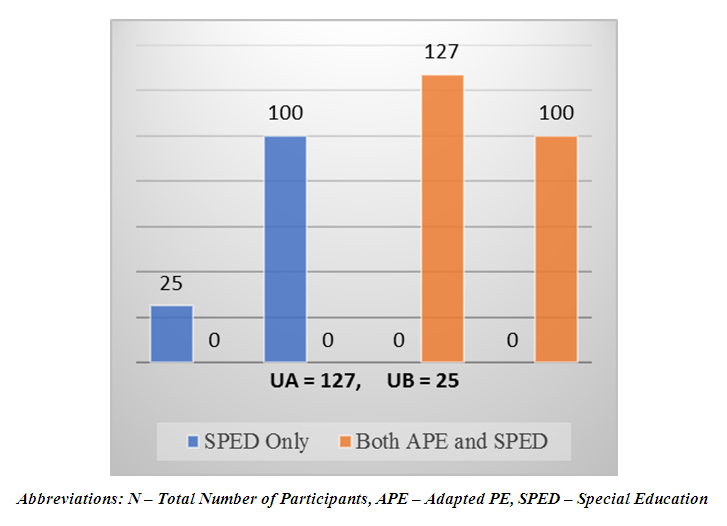

- The research design used for the study was the mixed method design. A mixed- method research design involves collecting and analysing both quantitative and qualitative data in a single study in order to come out with a clear picture of the research problem (Frankael et al., 2015) [14]. This study focused on the two universities offering teacher education in PE. The study location was therefore two sites in the Central Region in Ghana, one in Cape Coast metropolis (University of Cape Coast, UCC) and the other one in Winneba municipality (University of Education, Winneba - UEW). These two institutions are very prominent in the history and training of PE teachers in Ghana and currently are the only universities in Ghana that train PE teachers. These unique characteristics of the two universities made it suitable for the researchers to undertake this study in these institutions. The sample size for the study was 152 2018/2019 level 300 student-teachers from University A (UA = 127) and University B (UB=25) who met the inclusion criteria of not having had any refresher courses in special needs education (SPED) apart from the university preparation programme. Third years were selected for this study because they have completed their 3 years on-campus coursework and are about to go out on internship and therefore stands at a better position to address questions and opinions requested in the questionnaire and during the FGD.The Attitude towards Teaching Individuals with Physical Disabilities in Physical Education (ATIPDPE) instrument designed by Kudlacek et al. (2002) [15] was adapted to collect data to measure the intentions of student-teachers towards including SWDs in their practical PE lesson. The instrument which is a 7-point Likert Scale was adapted and modified into 5-point Likert scale to make it readily comprehensible to respondents and to enable them to express their views without frustrations. The modification made in the instrument were; likely outcome was changed to Agree and unlikely outcome to disagree to make it easier for the participants to answer them. Also, the normative belief aspect was taken off because of the participants used for this study who are yet to interact with parents and other staff. Part I was about the definition of disability and inclusion. Part II contained 4 items related to intention, 10 items on behavioural beliefs was modified to 7 items, and 7 items on perceived control beliefs was modified to 5 items. The questionnaire also contained an aspect where participants were asked to indicate courses taken during their university training programme that involves SWDs. The adapted instrument was given to specialists in the area for content and face validity. For content validity the experts ensured that the items on the adapted standardized instrument measures the purpose of the study. The ATIPDPE instrument has a reliable Cronbach alpha coefficient between .71 and .94 (Kudlacek et al., 2002). Due to the adaptations made in the instrument, a test-retest was used to check for the reliability of the tool. The researcher administered the questionnaire to a selected sample of 15 student-teachers who did not form part of the sample size for the study. SPSS was used in calculating the Cronbach alpha coefficient for the reliability of each scale of the instrument. The Cronbach alpha for the intention of student-teachers to teach in an inclusive setting scale was α = .93. The reliability for behavioural belief outcome of inclusion in a practical PE lesson scale was satisfactory with α = .76; and the student-teachers’ perceived control beliefs toward inclusive practical PE scale yielded a reliability of α = .77.Prior to data collection, ethical clearance was sought from UCC IRB board (ID number: UCCIRB/EXT/2019/16). Permission from institutional departmental heads and the study participants’ consents were sought for with participants assured of confidentiality and freedom to quit the study without reprisal. The questionnaire was administered in English since the medium of instruction in all Ghanaian schools from basic one to the university level is English. The researchers accessed the students at their lecture halls at a prearranged date and time. The researchers with the help of the two study assistants administered the questionnaires. The completed questionnaires were collected immediately after they were filled out. The research team looked through the filled questionnaire to ensure that all the items had been completed before releasing the respondents. Quantitative data were clean then coded using SPSS Version 25. Data cleaning was carried out to ensure that incomplete data, incorrect formatting, duplication and coding inconsistencies from the data set was corrected or removed where necessary before carrying out the analysis. Quantitative data were analysed using descriptive statistics of frequencies and percentages, which were presented in tables and chart. Hierarchical multiple regression was used to ascertain which variable predicts intention of student-teachers to include SWDs in practical PE lessons. For data scoring, the scale ranged from 1 to 5 with 1 – representing Strongly Disagree, 2 – Disagree, 3 – Undecided, 4 – Agree and 5 – Strongly Agree. The summative index for each category of the questionnaire was derived by adding the ratings of the total number of items. For instance, the summative index for the intention subscale was derived by adding the ratings of the four intention statements (I1+I2+I3+14=TI). In tabular presentation of the results, strongly agree and agree as well as strongly disagree and disagree were merged together where necessary. For the hierarchical regression analysis, the most important independent variable was entered first in this case the behavioural belief summative index followed by perceived behavioural control belief summative index. Based on the results from the questionnaire, a followed up 30 minutes focus group discussion (FGD) was carried out with 20 (16 and 4) of the same participants who were proportionally selected. During the FGD session, one question was posed to ascertain student-teachers’ intentions to include SWDs in their practical PE lessons in an inclusive setting. The FGD was first carried out with 5 students from University B followed by 15 proportionally selected level 300 student-teachers from University A who were put into three groups of five. Masters lecture rooms in both institutions were used for the FGD. Qualitative data were transcribed verbatim and analysed using phenomenological analysis. Confirmability and member checking were ensured as audio and data transcribed were confirmed with participants.

3. Results

- Essential Courses for Inclusion in the University Preparation Programme

| Figure 1. Courses Studied Relating to Disability in the University PE Programme |

|

|

|

|

|

4. Discussion

- Teachers in various countries worldwide have been confronted with the placement of SWDs in general classes (Hutzler et al., 2019) [16]. Based on this, teacher education programmes need to embrace courses that will help equip pre-service teachers to be able to include SWDs in their inclusive class settings. In teacher education, courses in the field of disability are seen as fundamental. These can have positive effect on pre-service teachers perceived competence to work with SWDs in inclusive settings (Florian, 2012) [17]. In view of this, all student-teachers from University A reported having taken a course in both APE and SPED while those from University B indicated taking a course in only SPED. A course in APE focuses on current concepts, trends, methods, and instructional strategies and adaptations in APE, inclusion, and students' abilities to assess, plan and implement a PE unit/lesson designed to meet the unique needs of SWDs. Meanwhile, a course in SPED covers knowledge regarding identification of SWDs, the nature of different disabilities, their causes and characteristics. There was inconsistency found between the preparatory programmes in the two universities. The finding of the present study agrees with what Swanson et al. (2013) [18] discovered when they interviewed teachers to identify aspects of university coursework that contribute to their ability to implement inclusion, and found that there was a lack of consistency across the teacher preparation programme within the universities. Similarly, Di Nardo et al. (2014) [19] established that pre-service PE teachers who received additional APE courses had higher positive intentions and attitudes towards teaching SWDs than those who did not. Findings from the current study showed that the majority of the participants have the intentions to include SWDs in their practical PE lessons. This was revealed in both the results of the questionnaire items and the FGD where the student-teachers expressed their willingness to include SWDs in their practical lessons. The current finding is in line with that of Rust and Sinelnikov (2010) [11] who found that modules in APE develop student-teachers’ intention towards teaching SWDs. However, this could differ based on the methodological approach and mindset of the student-teachers. This implies that a basic introductory course in APE as part of the preparation programme will expose student-teachers to basic knowledge in inclusion and consequently influence their intention to include SWDs in their practical PE lessons. Contrary to this current finding, Hwang and Evans (2011) [20], found that of the 29 South Korean teachers they analysed, most of them (55.2%) were reluctant to include SWDs in general education, although slightly more than half (58.6%) of the participants believed in the benefits of inclusion. The result of the current study indicated that student-teachers perceive the outcome of inclusion to be crucial if only their perceived control beliefs (i.e. appropriate training and availability of special equipment and facilities) are met in the inclusive schools more than their behavioural beliefs. This current finding falls in line with that of Hwang and Evans’s (2011) [20] report that 75.8% of their sampled teachers perceived a lack of school support and adequate resources as obstacle for the inclusion of SWDs. This denotes that when student-teachers presume to have acquired adequate training as well as perceive that they will have support in the form of equipment and facilities from inclusive schools, they are ready to include SWDs in their practical lessons.According to the theory of Planned Behaviour by Arjen (1991) [6], intentions are predicted by one’s behavioural beliefs, normative beliefs and perceived behavioural control beliefs. Hierarchical regression results in the present study showed perceived behavioural control beliefs contributing more (32.0%) to predicting intention than behavioural beliefs with R2 change of 14.0%. The current finding agrees with what Fournidou et al. (2011) [21] found that perceived behavioural control had the strongest relationship on intention to include SWDs in general PE than behavioural beliefs. Also, in support of the present finding, perceived behavioural control among other TPB components (attitude, moral norm, affective beliefs, and social norm), were identified to determine the intentions of PE teachers to teach SWDs in their inclusive teaching practise (Wang et al., 2015) [22]. The current finding implies that the combination of attitudes toward a behaviour, and behavioural control forms a behavioural intention, which can be defined as an indication of a student-teachers preparedness to accomplish a given behaviour (in this case inclusion of SWDs in practical PE lessons). University preparation programmes should, therefore, foster the intentions of the student-teachers for inclusive practical PE teaching. This suggests that the PE content covered in teacher preparation programmes should be relevant and adequate to impact student-teachers’ intentions. This, if ensured, is likely to trigger higher inclusion of SWDs in practical PE lessons.

5. Findings and Conclusions

- Coursework in both APE and SPED tends to expose student-teachers to inclusive teaching than coursework solely in SPED. In this case, coursework in both SPED and APE reshape the intentions of student-teachers for positive inclusion. Unfortunately, APE was found not to be part of the University B programme. The findings indicated that student-teachers from both universities have intentions to include SWDs, however, they entertained fear due to perceived lack of appropriate training and fear of support in terms of equipment and facilities in an inclusive setting. It was revealed that student-teachers believed inclusion would not slow down their practical lessons or make skill teaching difficult. Perceived control belief was found to predict the intention of student-teachers to include SWDs in practical PE lessons than behavioural belief did. The study therefore concludes that when student-teachers perceive adequacy in their general preparation programme for inclusion in terms of content, pedagogy and exposure, they have intention of including SWDs in practical PE lessons. This study recommends that university coursework in Adapted Physical Education and Special Education should be modelled in line with inclusion to help student-teachers to frequently reflect on their beliefs and intentions of teaching SWDs in practical PE lessons.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- The researchers thank all student-teachers from the two institutions who agreed to participate in this study. Further thanks go to all research assistants who participated in this study.Declaration of Conflict of InterestsThe authors declare no conflict of interest.FundingThe authors received no financial support for this research or publication of this article.Ethical approvalEthical clearance for this study was sought from the institutional review board of UCC. Permission was also sought from the two institutions in Ghana. Informed consentStudent-teachers consent was obtained prior to data collection.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML