-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Education

p-ISSN: 2162-9463 e-ISSN: 2162-8467

2020; 10(3): 49-58

doi:10.5923/j.edu.20201003.01

Received: March 30, 2020; Accepted: May 6, 2020; Published: August 15, 2020

Relationship between School Incentives and Effectiveness of Student Councils in Kenyan Secondary Schools

Stephen O. Adongo 1, Jack Odongo Ajowi 2, Peter JO Aloka 2

1Master’s Student in Educational Administration & Management, Jaramogi Oginga Odinga University of Science & Technology, Bondo, Kenya

2School of Education, Jaramogi Oginga Odinga University of Science & Technology, Bondo, Kenya

Correspondence to: Peter JO Aloka , School of Education, Jaramogi Oginga Odinga University of Science & Technology, Bondo, Kenya.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2020 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

The study investigated the relationship between school incentives and effectiveness of student councils in promoting discipline in secondary schools in Bondo sub-county, Kenya. The study was based on functional leadership theory. The study was based on mixed method approach. The study uses Concurrent triangulation design within the mixed method approach. The study targeted 1636 prefects, 280 teachers, 43 principals, 43 school captains and 49 deputy principals in 43 secondary schools in Bondo sub-county. A sample size of 491 prefects, 86 teachers, 13 principals, 13 school captains and 15 deputy principals was obtained. Questionnaires were used to obtain data from prefects and teachers while an interview schedule was used to obtain information from principals, school captains and deputy principals. To ensure face, content and construct validities of the research instruments, supervisors and members of the school of Education at Jaramogi Oginga Odinga University of Science and Technology who are experts in this area of study scrutinized the research instruments. Test re-test method of establishing reliability of questionnaires was used. Quantitative data from questionnaires were analyzed using descriptive statistics and inferential statistics such as Pearson’s product moment correlation and regression analysis. Thematic analysis is essentially a method for identifying and analyzing pattern in qualitative data. The findings indicated a strong positive relationship (r = .635) between school incentives and effectiveness of student councils. It is recommended that the Kenyan Ministry of Education should develop a manual for prefects training and mentorship for secondary schools for effectiveness of students’ councils.

Keywords: Relationship, School incentives, Effectiveness, Student councils, Discipline, Secondary schools

Cite this paper: Stephen O. Adongo , Jack Odongo Ajowi , Peter JO Aloka , Relationship between School Incentives and Effectiveness of Student Councils in Kenyan Secondary Schools, Education, Vol. 10 No. 3, 2020, pp. 49-58. doi: 10.5923/j.edu.20201003.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Student participation in school administration, if properly organized and supervised, offers opportunities for developing students’ morale, cooperation, prudent leadership and intelligent followership and also increases in discipline, self-direction and dependence. It also enables schools to mobilize all its forces for a comprehensive program of activities. Student participation provides better opportunities for teachers to gauge the special abilities of their pupils than as afforded by curriculum program of the school. It also makes it easy for the administration of the school as the responsibility for organizing activities and for maintaining discipline which is actually shared by the teachers, students and the school administration even though the ultimate and official responsibility in these matters lies with the principal (Kochhar, 2007). Developing countries have similarly been affected by student indiscipline problem. In countries such as the Trinidad and Tobago, the Ministry of Education (2005) considered the issue of student discipline a deteriorating big problem. In Tanzania, teachers are meant to have absolute powers over students, visible in methods of reward or punishment used by the teacher because of student indiscipline.Prefects play a very important role in the control of students and maintenance of student discipline in public secondary schools. They carry out the implementation of instructions from the administration and teachers. There is need for every school to have an efficient and effective prefects system in order to assist in running the school well. Every school should adopt ways of establishing such system through proper prefect selection, in-house training of prefects in effective leadership, team work and team building, proper standards, values and attitudes, good communication and time management. Becoming a prefect is a valuable goal and the position of prefect forms a valuable part of a pupil’s personal development, opening their minds to new levels of responsibility and participation in a very positive way. Prefects are a tremendous help to the school and play a particularly important role in mentoring younger pupils (Denton, 2003). They are delegated duties concerned with day-to-day life in school. These include coordination of co-curricular activities, dealing with minor cases of discipline and taking responsibility for students’ welfare.Njue, (2015) revealed that majority of prefects were being inducted by the school administration. However, some reported the induction process to have been carried out by all stakeholders who included outgoing prefects, school administration, teachers and resource persons. Katolo (2016) established that principals in their respective secondary schools encourage open door policy where studies are free to see the head of the institution to explain their problems. There have been various types of students’ leaders in the history of teaching and learning. These leaders include prefects, captains, councilors, ministers and student councils (Muli, 2007). Students’ Governing Councils (SGC) is mainly found in higher institutions of learning like the universities. Students elect their leaders who represent their grievances to university management. Ministers are students’ leaders in tertiary institutions like Teachers Training Colleges.The study was based on functional leadership theory. The Leadership theory (Hackman and Walton 1986; Posner, 1995) is a leadership theory responding to specific leaders behavior aimed to positively develop organization or to increase the effectiveness at different levels. Sansgiry, Chanda, Lemke and Szilagyi, (2006) evaluated the effect of incentives on student performance on comprehensive cumulative examinations administered at the College of Pharmacy, University of Houston. The results indicated that the passing rates were much higher throughout the time period for Milemarker III due to the high-stakes incentive of stops on progression to the next year. Oliver (2010) has shown how rewards and punishments may be used as components of collective action. According to that study, selective incentives, in the form of rewards and punishments, may be used to reward those who comply with the required actions and punish those who are noncompliant. Eberts, Hollenbeck and Stone (2012) reported that, although merit-based pay systems may increase student retention in class, they have no effect on student grade point averages, reduced attendance, or increased student failure. Nyongesa (2017) states that rewards when used a disciplinary technique, are symbols of approval from authority and are used to control and motivate good learning. They spur both workers and students to greater achievements. On the other hand rewards may have negative effects on the recipients if not carefully administered.Literature on incentives and effectiveness of school prefects exists though there are varied findings. Adebajo, Simileoluwa, (2018) results show that monetary incentives and near monetary incentives have no significant effect on “effort” while non-monetary incentives have a significant negative effect on the effort of teachers. This could imply that the issues underlying the current state of productivity of Public school teachers in Lagos State run deeper than remuneration or accountability. Woessman (2010) results showed that using teacher salary adjustments to reward great performance is significantly associated with mathematical, science, and reading achievement in the sample. Adebajo, (2018) showed that monetary incentives and near monetary incentives have no significant effect on “effort” while non-monetary incentives have a significant negative effect on the effort of teachers. This could imply that the issues underlying the current state of productivity of Public school teachers in Lagos State run deeper than remuneration or accountability. Imberman and Lovenheim (2015) showed comprehensively that teachers respond to incentives when the stakes are high enough, and student achievement rises in response to stronger group incentives as a result of increases in teacher effort.In Kenya prefects assist in maintaining discipline (Griffin, 1996). In Kenya, students’ leadership is composed of prefects who are appointed by the teachers. In this method, students do not have much input in the process. The principal, deputy principal and the teachers have heavy influence in the process of selection of the students’ leaders. This has been a major source of conflict between the school administration and students’ body where they feel that the students’ leadership is not reflective of their preferences as indicated during the election process (Oyaro, 2005). In Kenya, violent high schools strikes are a common occurrence. In 2008, for instance, the incidence of high school strikes rose by 34% (Ojwang, 2012). There are several causes that have been associated with high school students’ infringements, unrest which eventually leads to violent strikes. One of the causes that have been identified is high handedness by school administrations. In Kenya for example, the decision making process in high schools pertaining to matters that affect students’ welfare mainly involves the board of managements, principals and teachers. Usually there is little input from students who are primarily affected by the policy implementation.Schools in Bondo Sub County in Kenya have in recent past experienced cases of defiant students who openly confront their teachers and destroy school property, and reports from Bondo Sub county Education Office indicate that behavior problems manifest themselves in the form of open defiance to teachers, truancy, vandalism of property, sneaking out of school and so on (Bondo Sub County Education Office, 2015). Despite the formation of Kenya Secondary Schools Students Council (KSSSC) in 2009 by the Ministry of Education with a view to make secondary schools governance more participatory by including students in decision making structures in schools management, students’ indiscipline, in Bondo sub-county remains relatively high. Literature on factors affecting the effectiveness of students councils in secondary schools exist though they are scanty in nature. For example, Kinyua (2015) study investigated how factors such as students’ councils election process, students’ councils’ size and school size influence effectiveness of students councils in Kirinyaga East Sub-County, Kenya. Okonji (2016) established how the factors such as principal’s administrative experience, election process, extent of students’ council involvement and communication channel influence Students’ council Involvement in Public Secondary School Management in Emuhaya Sub-County, Vihiga County, Kenya. From the existing studies, very scanty information was available on school incentives, which the present study focused on.

2. Research Methodology

2.1. Research Design

- Concurrent triangulation design was used in this study since it ensures that both qualitative and quantitative data are handled at the same time. In this study as advanced by Creswell and Plano (2007), and cited in Creswell (2009), it enables the researcher to not only collect and analyze both quantitative and qualitative data, but it also involved the use of both approaches in random so that the overall strength of a study is greater than either qualitative or quantitative research.

2.2. Study Participants

- The study targeted 1636 prefects, 280 teachers, 43 principals 43 school captains and 49 deputy principals in 43 secondary schools in Bondo sub-county (Bondo TSC data, 2019). Principals, school captains and deputy principals are considered to be better placed to provide information during interviews. The sample size was obtained using the 30% according to Gay (2010) who observed that 10-30% of a given population is a representative sample. A sample size of 491 prefects, 86 teachers, 13 principals, 13 school captains and 15 deputy principals was obtained. Prefects and teachers were obtained using stratified and simple random sampling techniques. The principals, school captains and deputy principals were obtained using purposive sampling technique.

2.3. Instruments of Data Collection

- The researcher employed both questionnaire and interview for data collection (triangulation). Guion (2011) contends that use of more than one method of data collection, counters the weakness of one method and helps to gain highest level of validity and reliability. Ahuja (2007) support this view by asserting that advantages of good research design can be realized if more than one method of data collection is used for no one method of data collection is perfect. This study involved both questionnaire and interview because the study intends to collect both quantitative and qualitative data. Each questionnaire comprised of five point Likert scale, open-ended and closed- ended questions. The interview schedule was administered to the head teachers. To ensure face, content and construct validities of the research instruments, members of the school of Education at Jaramogi Oginga Odinga University of Science and Technology who are experts in this area of study scrutinized the research instruments. Their suggestions were incorporated in the questionnaires before preparing the final copy for data collection. From the reliability results, the subscale in the dependent variable (Effectiveness of Students Councils) questionnaire had an internal consistency of α = .782; all the items of this subscale were worthy of retention. The subscale “school incentives” which consisted of 7 items had Cronbach’s Alpha of α = .869.

2.4. Data Collection Procedures

- Permission to conduct the study was sought from National Commission for Science Technology and Innovation in Kenya. Thereafter, the researcher delivered letter to the principals of the sample schools, sought permission to use their institutions for this study and also to involve teachers and students in their schools in the study. Interview responses were tape- recorded and the researcher also took notes as this went on. Each participant was interviewed between 30 to 45 minutes while the filling in of questionnaires was approximately 30 minutes for each respondent. The researcher issued the questionnaires to be filled and thereafter collect them.

2.5. Data Analysis

- Both quantitative and qualitative data were analyzed. Quantitative data from closed-ended sections of questionnaires were analyzed using descriptive statistics such as frequency counts, percentages and means. In addition, inferential statistics such as Pearson product moment correlation and regression analysis were also used to test the hypotheses. Thematic analysis is essentially a method for identifying and analyzing pattern in qualitative data (Braun & Clarke, 2006) as cited by Raburu (2011) thematic analysis is identifying and reporting themes and patterns within data and describes data in rich details.

3. Findings & Discussion

3.1. Return Rates of Instruments

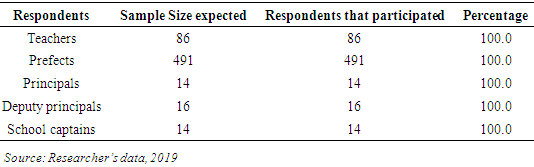

- The study found that 491 prefects and 86 teachers duly filled the questionnaires and returned for analysis, while 14 principals, 16 deputy principals and 14 school captains participated in the interviews. This implies that the study achieved response return rate of 100.0% for all the respondents. Table 1 shows the summary of the response return rate.

|

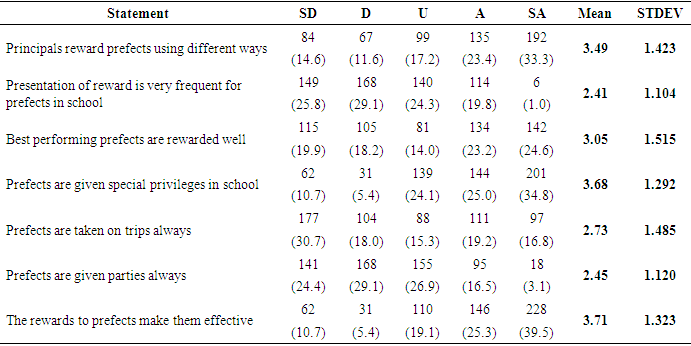

3.2. Descriptive Findings on Extent of Use of School Incentives and Effectiveness of Student Councils

- School incentives influencing the effectiveness of student councils in promoting discipline was measured using a 5-point Likert scale as on scale of 1 to 5 where 1 = strongly disagree (SD), 2 = disagree (D), 3 = neutral (N), 4 = agree (A) and 5 = strongly agree (SA). The data obtained was analyzed to show frequency of each response as well as percentage per item. The results are as shown in Table 2.

|

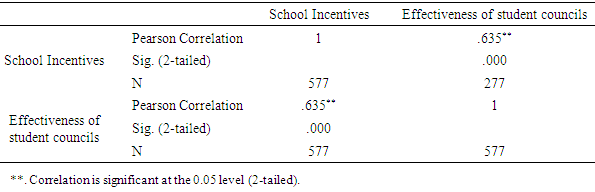

3.3. Correlational Analysis between School Incentives and Effectiveness of Student Councils in Promoting Discipline

- The null hypothesis was stated as follows:H01: There is no statistically significant relationship between school incentives and effectiveness of student councils in promoting discipline in secondary schools in Bondo sub-county, Kenya.To establish whether there was any significant relationship between school incentives and effectiveness of student councils in promoting discipline in secondary schools, a Pearson Correlation analysis was conducted between the two variables. Since data for school incentives and effectiveness of student councils in promoting discipline were measured on ordinal Likert level for each item, it was important to obtain continuous data to facilitate performance of correlation analysis. Thus, summated scores for each respondent were obtained for each of the two scales. The corresponding scores for each respondent were used as data points for the 577 participants (teachers and prefects). The null hypotheses were to be tested at 0.05 significance/alpha level (α). The test statistic is converted to a conditional probability called a p- value. If p≤α, the null hypothesis is rejected, meaning that the observed difference is significant, that is, not due to chance. However, if the p- value will be greater than 0.05(i.e., p>α), the null hypothesis will not be rejected (we fail to reject the null hypothesis), meaning the observed difference between the variables is not significant. The correlation output is presented in Table 3.

|

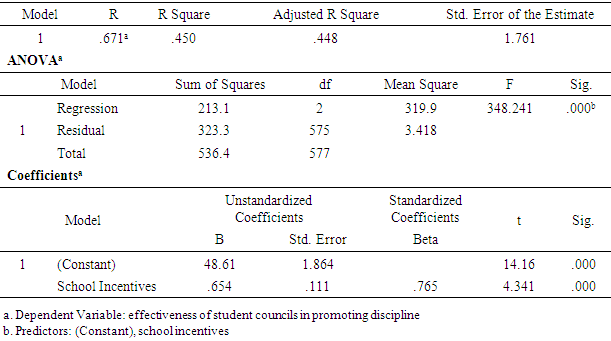

3.4. Regression Output for School Incentives and Effectiveness of Student Councils in Promoting Discipline

- To determine the relationship between a school incentives and effectiveness of student councils in promoting discipline, regression analysis was conducted between the variables. Data collected was converted to continuous data by summating the individual item scores in the scale for each respondent. Data obtained from the 577 respondents effectively provided 577 data points. The regression output is presented in Table 4.

|

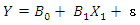

Where Y is effectiveness of student councils in promoting discipline, B0 is Coefficient of constant term, B1 is coefficient of school incentives, X1 is school incentives and

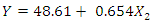

Where Y is effectiveness of student councils in promoting discipline, B0 is Coefficient of constant term, B1 is coefficient of school incentives, X1 is school incentives and  is error term. Thus, replacing the coefficients of regression, the equation becomes;

is error term. Thus, replacing the coefficients of regression, the equation becomes; This shows that, when school incentives change by one positive unit, effectiveness of student councils in promoting discipline increases by 0.654. Thus, school incentives positively affect effectiveness of student councils in promoting discipline to a magnitude of 0.654 as indicated by the main effects.

This shows that, when school incentives change by one positive unit, effectiveness of student councils in promoting discipline increases by 0.654. Thus, school incentives positively affect effectiveness of student councils in promoting discipline to a magnitude of 0.654 as indicated by the main effects. 3.5. Qualitative Findings

- Incentives are factors that motivate or encourage an individual to perform an action. In the present study, it was reported that there were several incentives that prefects were entitled to in different schools. The themes that emerged on incentives included prefects’ motivational trips, material gifts, special meals during meetings, special privileges and the provision of certificates of recognition.Prefects’ motivational tripsIn most schools, prefects’ trips were reported as one of the major incentives that the school administration provided. This meant that each year the school took the prefects for a trip at some designated place where they discussed various ways of school management as directed by the school administration. This was done to give prefects time to reflect on the leadership styles and effectiveness and it helped to make the schools more effective in terms of the leadership effectiveness. Some respondents reported that:“We have field trips for our prefects and these are meant for bonding purposes since we bring motivational speakers during such times. We always take our prefects outside the sub-county for such refresher tours and it has helped us so much” (deputy principal, 1)“School prefects are taken for training and trips far away meant to make them happy and feel cared for by the school administration. This has made us work hard because we feel appreciated by the school for the lots of work we do in school” (school captain 1)From the interview excerpts, it can be concluded that the use of trips for prefects has enhanced effectiveness of most school councils as the prefects become more committed to their duties in school. These trips make the prefects to have high morale as they see themselves as very close to the school administration and hence they become more effective in their leadership functions in school. This finding is contrary to Adebajo, (2018) which reported that monetary incentives and near monetary incentives have no significant effect on “effort” while non-monetary incentives have a significant negative effect on the effort of teachers.Material giftsThis refers to the provision of material gifts such as bread weekly, new sets of uniforms, different types of uniforms to the prefects in school. Most respondents reported that the school administration provided varying types of gifts to the school prefects to make them to become more motivated in their work in school. Some school administration provided bread to prefects once a week, others provided new uniforms to prefects each year and others gave a unique type of uniform to the prefects. Some respondents reported that:“The prefects in our school are given gifts like grey sweaters and green ties which are different from what other students put on. This has boosted the morale of the prefects. They feel special by such kind of treatments given to them” (school captain, 4)“The prefects are provided with red school ties each year for ease of identification and motivation. This has made them to be very committed in school because they feel recognized by the school administration” (deputy principal, 3)“We give a different of colour of shirt and tie to the school prefects each year we appoint them and this motivates them to a great extent. The prefects feel valued by us and they give their best in their work in school” (principal, 1)From the three interview excerpts, it can be concluded that the use of material gifts is very helpful in motivating the school prefects to do their work well while in school. The school prefects feel appreciated and they give their best. Thus, there is a very high and strong positive relationship between the provision of material gifts and effectiveness of school councils in schools. This finding agreed with Woessman (2010) study which reported that using teacher salary adjustments to reward great performance is significantly associated with mathematical, science, and reading achievement in the sample.Special meals during meetingsThis means that the school administration provided special meals to the prefects during their meetings in school. The prefects are also given refreshments on such meetings. Such incentives made prefects feel special as compared to the other students. The prefects would then give back by working extra hard in their school duties in school. This has made the students councils to be highly effective in discharging their leadership duties in school. Some respondents reported that:“Some refreshments are given to the prefects when they have meetings in school. We give them some meals which are special to the prefects such as chicken and rice. This makes them feel special and motivated” (principal, 4)“We give our prefects bread and special tea during meetings and this makes them feel part and parcel of the system. The prefects then discharge their duties more effectively hence they are key players in the day to day running of schools” (deputy principal, 5)“The school has a policy of giving prefects bread and other special food during our meeting with deputy principal and other school officials. This makes prefects feel very special and they in return work very hard in school” (School captain, 5)From the three interview excerpts with the respondents, it can be concluded that the provision of special meals during meetings in school increases the effectiveness of student councils. The prefects thus are highly motivated to work extra hard and give their best in their leadership duties. This finding is contrary to Adebajo, (2018) study which showed that monetary incentives and near monetary incentives have no significant effect on “effort” while non-monetary incentives have a significant negative effect on the effort of teachers.Special privilegesThis refers to certain special advantages or rights possessed by an individual or group. The prefects were reported to be having certain privileges given to them by the school administration to make them more effective in their duties. The respondents reported that in most schools, the prefects had a first chance to serve their meals in the school dining halls, in other schools; they were not punished in front of other students in case they made mistakes while in school. In the boarding schools, most schools provided separate rooms for prefects so that they did not live with other students. Some respondents reported that:“In our school, we are given several privileges like special time in the dining hall during meal times. We do not make lines such as other students. This makes us feel special in some way and makes us more effective in our leadership roles in school” (school captain 10)“We have provided several privileges to our prefects as you know we need to make them happy and special all the times. This is very helpful in making them more effective in discharging their duties in school. At times, we give them a special meal once in a while when we meet with them to provide guidance and direction on various matters” (principal, 7)“Privileges are a lot for the prefects in our school. We give them some consideration if they are very good in class and they lack fees. We consider their cases if they present them to us in time. We are keen on assisting the prefects when they are in need” (deputy principal, 9)From the three interview excerpts with the respondents, it can be concluded that, the different forms of privileges that are given to prefects in school were very effective in making the more committed to their leadership roles and student management. This finding agreed with Imberman and Lovenheim (2015) study which reported that teachers respond to incentives when the stakes are high enough, and student achievement rises in response to stronger group incentives as a result of increases in teacher effort.Provision of certificates of recognitionThis means that prefects are provided with certificates of recognition for their efforts in service to the school. This was reported to be done in most schools each year during the prize giving days. The outstanding prefects with great leadership qualities were rewarded and given certificates to appreciate their work. This was helpful in motivating the prefects to work extra hard in their duties in school. Some respondents reported that:“We are given certificates of recognition by our principal each year of work to appreciate us. This makes us feel that the school is aware of what we do. These certificates can help us in future when applying and there is need for evidence of leadership qualities in us. We believe this will give us upper hand” (school captain, 11)“In our school, we give our prefects certificate each year at the prize giving ceremonies. This motivates them and makes the councils to be more effective” (deputy principal, 6)From the two interview excerpts with the respondents, it can be concluded that the use of certificates of recognition for prefects for their good works and effort each year is very helpful in helping in enhancing the effectiveness of the students’ councils in schools. The school administration that adopts various incentives is likely to have more committed students’ councils in their schools. This finding agreed with Imberman and Lovenheim (2015) study which reported that teachers respond to incentives when the stakes are high enough, and student achievement rises in response to stronger group incentives as a result of increases in teacher effort.However, in some schools, it was reported that there were no incentives that are given to the prefects to appreciate them. The respondents reported that the schools did not have programmes for rewarding the prefects for their efforts that they put in school. This dampened the efforts of the school prefects in their leadership duties in school. One respondent reported that;“There are no incentives for prefects in our school and we are all the same like other students. We are treated the same way and no other things are given to us as prefects in school. We work hard, but not as others because we feel not motivated to do much more in school” (school captain, 8)From the interview excerpt, it can be concluded that the lack of incentives negatively affected the performance and commitment of the prefects in schools. The leadership effectiveness of such student councils is negatively affected by the lack of incentives in place for prefects. This finding is contrary to Adebajo, (2018) study which showed that monetary incentives and near monetary incentives have no significant effect on “effort” while non-monetary incentives have a significant negative effect on the effort of teachers.

4. Conclusions & Recommendations

- There is a strong positive relationship between school incentives and effectiveness of student councils in promoting discipline in secondary schools. This implies that statistically the more school provide incentives and rewards for the school prefects or students’ council, the more likely student councils would be effective in promoting discipline. This shows that, when school incentives change by one positive unit, effectiveness of student councils in promoting discipline increases by 0.654. Thus, school incentives positively affect effectiveness of student councils in promoting discipline to a magnitude of 0.654 as indicated by the main effects. The use of trips for prefects has enhanced effectiveness of most school councils as the prefects become more committed to their duties in school. These trips make the prefects to have high morale as they see themselves as very close to the school administration and hence they become more effective in their leadership functions in school. It can be concluded that the use of material gifts is very helpful in motivating the school prefects to do their work well while in school. The school prefects feel appreciated and they give their best. The provision of special meals during meetings in school increases the effectiveness of student councils. The different forms of privileges that are given to prefects in school were very effective in making the more committed to their leadership roles and student management. School principals should identify incentives that are effective in motivation of members of students’ councils. This is because the study reported a positive relationship between incentives to prefects in schools and effectiveness of students’ councils.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML