-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Education

p-ISSN: 2162-9463 e-ISSN: 2162-8467

2020; 10(2): 33-40

doi:10.5923/j.edu.20201002.02

University Education in Nuclear Deterrence

1Air Force Institute of Technology, Air Force Nuclear College, Albuquerque, USA

2University of New Haven, Department of National Security, West Haven, USA

Correspondence to: Ian Kurtz, Air Force Institute of Technology, Air Force Nuclear College, Albuquerque, USA.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2020 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Large-scale social debates ubiquitously have disparate viewpoints with disparate constituencies, and thus education in such important social issues necessitate teaching and learning many difference opinions and perspectives. Teaching history and social sciences in today’s schools prepares students to address large-scale (perhaps catastrophically global) social issues like nuclear deterrence. The American center for strategic and budgetary assessments in Washington, D.C. announces the extraordinary monetary costs to maintain deterrence, and it is easy to argue those moneys could be better spent elsewhere, demanding critical thinking (stemming from solid education) of this global social issue. This manuscript explores nuclear deterrence education within United States civilian institutions of higher learning. The subjects of nuclear deterrence and nuclear weapons are prevalent throughout many academic programs and initial data indicates these topics are sometimes not taught in a balanced fashion, and the potential for bias can lead to demotion of some university education programs to comprise instead mere indoctrination. No doubt, nuclear weapons have a long and controversial history, but the current American national security strategy considers nuclear weapons vital to the ability to preserve peace and stability. Data analysis is performed in veins: qualitative examination of fifty-six nuclear weapons class syllabi and the vitas and curricula vitae (CV) of each instructor. Readings and assignments for each course were examined and each syllabus was searched for the presence of important key words, both positive and negative. Key words like deterrence, modernization, surety, victim, and abolish were crucial to understanding the scope of the classes. In addition, a study of the course instructor’s background provides a glimpse into their qualifications to teach in the subject area of nuclear weapons and deterrence comprehensively. Based on this methodology, each class and instructor were given an assessment, and the results reveal that some courses were taught in a negative and biased manner, and some instructors lacked sufficient background to teach such topics.

Keywords: Modernization of nuclear triad, Abolition of nuclear weapons, Nuclear deterrence, Deterrence, Modernization, Surety, Victim, Abolish, National security, University education

Cite this paper: Ian Kurtz, University Education in Nuclear Deterrence, Education, Vol. 10 No. 2, 2020, pp. 33-40. doi: 10.5923/j.edu.20201002.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- This manuscript evaluates the nature of nuclear weapons education in United States universities. An initial search of courses at various universities yielded interesting questions. The courses reside in a wide range of disciplines, including political science, history, and physics, but also included departments such as English, geology, peace studies, environmental studies, women’s studies. The courses frequently featured a distinct anti-nuclear bias. Important concepts such as deterrence, nuclear surety, or national security were rarely mentioned in the courses examined hinting of the potential for biased treatment. Instead, many courses concentrate on nuclear accidents, the dangers of nuclear weapons, and occasionally treated the nuclear bombings of Nagasaki and Hiroshima as war crimes. Course time was instead devoted to disarmament and nuclear activism. In fact, in some cases, faculty pride themselves in being firmly “anti-nuke”, and in some extreme cases, regularly engaged in anti-nuclear activism, reinforcing the suspicion that the courses could instantiate biased indoctrination as opposed to diverse, rounded education. Based on these initial observations, the research pursued the following question: Do universities teach nuclear subjects with an anti-nuke bias and is such an attitude prominent?Why conduct a review of nuclear education in the United States? For over seventy years, nuclear weapons have been at the forefront of national security in the United States (Rosenberg 1983) and Russia (McNamara 1983) and its predecessor. No fewer than thirteen U.S. presidential administrations have possessed a nuclear arsenal (Sands 2018), (Sands 2016), (Sands 2018). Today, there are thousands of employees in the government, military and private sector that deal with nuclear weapons every day. The budget for the acquisition, sustainment, maintenance, transportation, and security easily climbs into the billions of dollars each year. Over the next several decades, the United States nuclear arsenal will undergo a significant modernization program, and very lively debates are underway to ascertain the proper place of nuclear deterrence (Lieber 2009) and nuclear weapons in national security (Pearce 2018), (Dallas 2013), (Gardiner 2019). All areas of the nuclear triad, i.e., bomber aircraft, intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs), and submarines will see replacements of some kind. In addition, the United States will see new upgrades to various nuclear weaponry. Thousands of people throughout the United States government, i.e. military members, civilian employees, and defense contractors, will be involved in this venture. This motivates research into the state of the nuclear education enterprise and examine it for bias, since these employees and future leaders must be educated in all facets of the United States nuclear program (both positive and negatives aspects) in order to understand all opinions surrounding these controversial weapons, and to be able to lead the mission into the future. Furthermore, taxpayers should understand this process and its effect on United States national interests. Accepting the fact nuclear weapons are not going away soon merits an understanding of how academia treats this topic and illuminates potential futures.Preliminary research reveals the subject of nuclear weapons to be very polarizing, albeit a relatively popular area of study in United States institutions of higher learning. Many United States universities (as well as various government and military universities, schools, and colleges) offer courses in their curriculum. Some classes focus solely on nuclear weapons; others weave nuclear weapons into classes about weapons of mass destruction or general political science topics, and usually this area of study occupies a prominent place in both political science and homeland security departments, though as discussed here, can end up in some rather non-traditional locations. Because of the important role of nuclear weapons, and the many subjects that surround them, education in this field must be free from bias and provide many disparate points of view. Educators at all levels must present nuclear deterrence education, especially as it pertains to United States national security, in an objective, rational, and bias-free manner to permit an understanding of the deterrent value of nuclear weapons.For several years, the American department of defense (DOD) has identified (due to several failures in aspects of safety, security, and accountability) a need to educate professionals in all areas of the nuclear profession. The path towards robust education opportunities for government and military personnel in the nuclear enterprise began in earnest in 2006 with mistaken shipment of nuclear components to Taiwan (Donald 2008) and was followed quickly in 2007 with a nuclear incident at Minot and Barksdale air force bases (Raaberg 2007). Both of these events spurred multiple investigations, both internally and externally, and among many identified shortcomings was a decline and de-emphasis of nuclear-related education over the ensuing decades after the end of the Cold War (Spencer, 2012, p. 50). In the aftermath of these events, the Schlesinger Report (Schlesinger 2008) stressed the need for an expanded nuclear deterrence education program throughout the American air force and navy. In fact, the report recommended a complete review of nuclear education across all four services to strengthen understanding of deterrence theory, strategy, and policy (Schlesinger, 2008, p. B-1). Currently, The American air education and training command (AETC) has instituted various educational programs that encompass both military and civilian institutions to accomplish this goal (Sands, 2017), (Mihalik, 2018). Therefore, a review of at least some of these public offerings proves to be a necessary exercise. Furthermore, as early as the 1990s, the American department of energy (DOE), also identified a need for quality education for their employees who operate within the nuclear weapons industry. While some of these educational programs are self-evidently science-based, the DOE still requires programs that teach the deterrent value of nuclear weapons. Ostensibly, these students will go on to seek employment in DOEs nuclear science and engineering sectors, however, they will need a broader picture of how these weapons fit into the Grand National Strategy if they are to advance in their subsequent careers. Indeed, the 1999 Chiles Commission report understood that for the DOE, the education of its workforce relies on civilian institutions (Congress, 1999, p. 11).Today, nuclear policymakers require individuals with a robust nuclear education to understand the current shift in defense priorities. (McGiffin, 2019) argues that the priority as nation-states has moved beyond the war on terror and now focuses on inter-state strategic competition. National security thinkers now commonly refer to this as “great power competition”. Indeed, for deterrence to produce the desired effect, the industry demands a “well-educated cadre of deterrence thought leaders and practitioners” (McGiffin, 2019). Furthermore, McGiffin argues, the United States nuclear weapon program crosses the academic spectrum at the level of the whole-of-society. This means that we have a need for students, whether in the nuclear enterprise or not, to understand their deterrent value. This in turn, will enhance both the national discussion as well as the national will. Perhaps people who are afraid of nuclear weapons, do not understand their deterrent value, or question their safety, truly do not understand them or their purpose. Misinformation, falsehoods, (or for that matter, deliberate distortions) of the value of our nuclear deterrent, runs the risk of being accepted as factual by the American public (Chilton, 2019).

2. Results

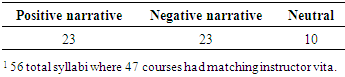

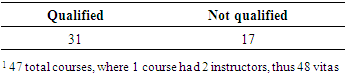

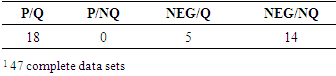

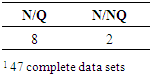

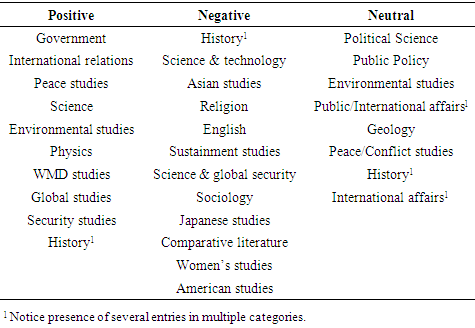

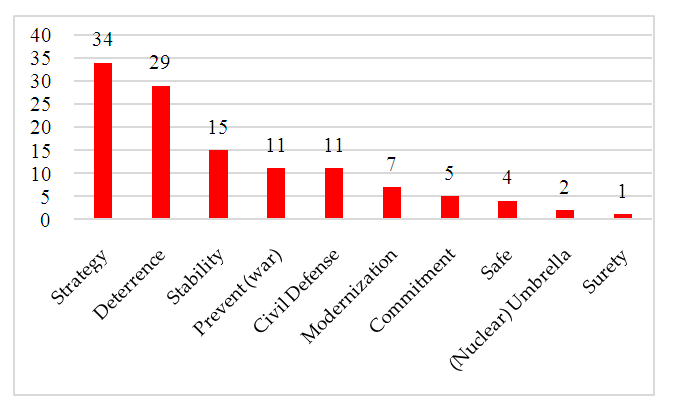

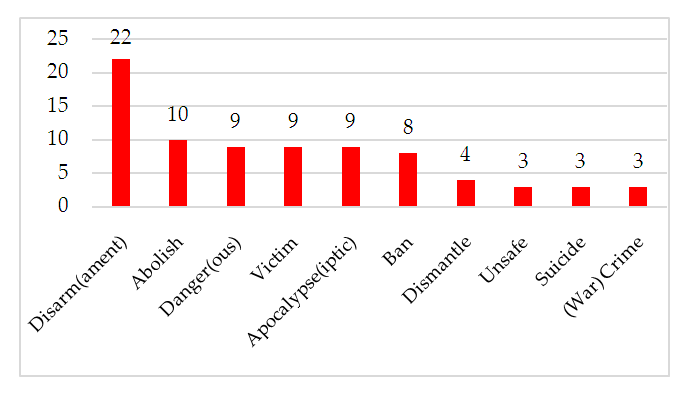

- The methodology consisted of an analysis of individual course syllabi and each instructor’s vita/CV. Fifty-six syllabi present in the newly funded distance learning education program (Sands, 2017), (Mihalik, 2018) were analyzed. Forty-seven of the course syllabi had a matching instructor’s vita, that of the person who taught the class. (Note: there were forty-eight vitas were analyzed, as one class had two instructors listed on the syllabus). These syllabi and vitas are henceforth referred to as the complete data sets. Nine courses had no information about the instructor, these are henceforth referred to as incomplete data sets. The first part of this research analyzed content of nuclear course syllabi. It is reasonably assumed that a course syllabus sets the tone for the class. Its course description, objectives, readings, and assignments tell the story of what to expect; it is a key document for someone wanting to understand the nature of the class. Initially, nearly one-hundred different syllabi were collected from colleges and universities from across the country. Initial review of these products yielded eighty-three syllabi that contained usable data, and the list of syllabi was winnowed down many for various reasons to fifty-six focusing solely on the subject matter of interest. Next, the data was analyzed for key words and phrases in the course description, objectives, and assignments. A list of positive terms was constructed with words like deterrence or stability. A list of negative terms included such words as danger, war crime, abolish, and victim. A review of the reading assignments was required next. The examination of the syllabi revealed an unbalanced amount of negative literature; an unbalanced focus on the dangers of nuclear radiation and the risk of accidents; featured negative terms; or lacked discussion of positive terms like deterrence. Such instances led to assessment as negative. On the other hand, if the curriculum featured deterrence-related readings, discussion, assignments or included the positive terms, then the assessment was positive. A third assessment, labeled as neutral, was used when courses were taught in a manner that highlighted several sides of the nuclear issue; and in these instances, were realities, challenges and benefits given equivalent treatment?The second part of this research involved an analysis of each course instructor. Admittedly, a risky venture fraught with contention, examination of each person sought to probe the instructors’ professional lives including their background seeking to make a cautious determination of the qualification to teach this subject matter in a rounded, diverse manner. In qualitative analysis, the documents were examined to extract several themes (Cresswell, 2014, p. 195). The methodology involved reading the instructors’ resumes, biographies, and/or curricula vitae to assess the academic background of each. The collection of the instructors’ biographical information compliments the data in the syllabi. This analysis was approached as if a hiring decision was sought for an instructor position. Typically, a university would require a history instructor to possess a history degree. For example, many open instructor positions teaching for the University of New Mexico require a “Master’s degree or higher in the discipline or subfield in which you are applying” (UNM, 2019). Therefore, if an instructor possesses a pertinent degree, such as political science or national security, or if a instructor’s background included writing, teaching or lecturing in nuclear deterrence, or served in relevant government positions, then the instructor was assessed as qualified. If the analysis found that academic pursuit of national security issues, nuclear weapons or deterrence was lacking, then the instructor was assessed as not qualified to teach such subjects. This is an important distinction. Not qualified is a more suitable designation than say, unqualified. The assessment as “not qualified” only refers to expertise in the subject matter, not overall teaching ability.

|

|

|

|

| Figure 1. Syllabi that feature the positive terms |

| Figure 2. Syllabi that feature the negative terms |

3. Discussion

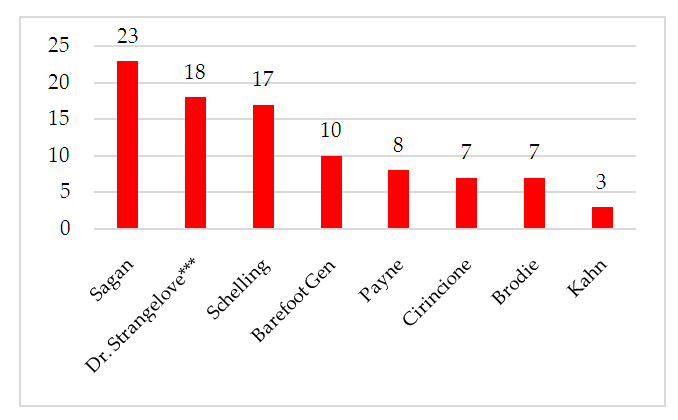

- The syllabi were also analyzed for prevalence of prominent works from the literature in the university courses as displayed in figure 3. The presence of six noted authors in the field of nuclear deterrence were sought: Bernard Brodie (Brodie 1968), Joseph Cirincione (Cirincione 2008), Herman Kahn (Kahn 1960), Keith Payne (Payne 2001), Scott Sagan (Sagan 2003), and Thomas Schelling (Schelling 1962). The results indicate many courses utilized Sagan and Schelling, but there was relatively little interest in Brodie or Kahn.

| Figure 3. Selected literature |

|

4. Materials and Methods

- The first wave of analysis brought out foundational data. Was a class positive or negative? Was the instructor qualified or not qualified? This was the initial examination of the data, and simply a straightforward, binary result. There were several key themes extracted from the syllabi and biographical research. The discussion appears below:

4.1. Use of Positive Terms

- Terms like deterrence made a major difference in the theme of each course. Without it, the courses likely earned a negative assessment. The importance of such a term cannot be understated. Courses that discuss the deterrent value of nuclear weapons were assessed as positive 90% of the time. The term is deemed to be the primary reason nations maintain a nuclear arsenal, i.e. to deter adversaries and assure allies. This topic must be inserted into the academic discussion.

4.2. Use of Negative Terms

- Though disarmament and abolish were mentioned in over half of the courses, they appeared in an equal amount of positive and negative classes. When some courses feature fallout literature, prominently feature the plight of the Japanese bombing victims, and consider the bombings war crimes, the narrative of the course can shift very quickly. In one negatively assessed class, an assignment required students to “describe the various ways people die in the atomic bombings…”.

4.3. Instructor Qualifications

- The instructor’s background, academic history, and research interests are critical to the theme of each course. As the analysis clearly showed, not qualified instructors do not teach courses that view nuclear weapons with a positive deterrent value and teach many of the negative courses. The opposite is true when the instructor was qualified to teach the course from a balanced perspective.

4.4. Academic Departments that Teach Nuclear Weapons or Deterrence

- Within the academic environment, when instructors teach nuclear deterrence courses as part of Political Science programs, the courses are overwhelmingly positive, while courses offered by a History Department were surprisingly negative, and its instructors were generally not qualified. An interesting finding about nuclear deterrence resided in the courses that appeared in History departments. It is notable that the subject of history may not be as straightforward as it may seem. The history website for the University of California at Los Angeles provides their definition of the nature of a history degree: “A history degree is probably the most flexible and far-ranging. It is excellent preparation for a wide range of fields – law, teaching, business, public service, journalism, and even medicine” (UCLA, 2019). Thus, the instructors come from a wide variety of backgrounds. Among the most interesting of the findings, it shows that history, as an academic discipline, is perhaps the most diverse in its approach and does not represent the practitioner perspective, as does the faculty of a Political Science department.

4.5. The Presence of Deterrence Literature

- The research revealed that there is lukewarm interest in the works of various classic deterrence theorists. The works of key authors represent the classic theory that surrounds nuclear arsenals and many readers regard these books as critical literature. The literary contributions of Kahn, Schelling, Brodie, and others are required in a robust discussion of nuclear weapons deterrent value. The implications of failing to include classic and contemporary deterrence theory can lead to a degradation of the deterrence education quality.

4.6. Questioning the Decision to Drop the Bomb

- Roughly half of the courses debate or question the decision to deploy atomic weapons on the Japanese Empire during WWII. Nearly 60% of those classes are negative. Though not entirely without benefit, such discussions often fail to take into consideration the national climate during WWII; the war had dragged on for several years with many soldiers killed. An instructor seeking to give a balanced consideration must present this subject in a way that considers the difficult decisions faced by our government leaders as well as public opinion of the day.

5. Summary

- While the instructors analyzed in this study are presumed to have their student’s best interests at heart, there appears to be gaps in their qualifications to serve as subject matter experts on nuclear weapons/deterrence where qualification is defined by a background in the disparate aspects of the topics being taught. Many instructors lack the background, both professionally and academically, to confront this topic. In some cases, the classes reside in inappropriate academic departments and often the subject matter is misaligned with the instructor’s experience. The implications of these findings are perhaps most critical to the research question. What benefit would a practitioner (or interested student) gain from an instructor who does not possess the tools to provide a robust deterrence discussion?Qualified instructors typically design course content of multiple types to maximize academic thought and diverse discussion. If seeking not to merely advocate and indoctrinate, the material should be presented in an unbiased manner that examines many sides of the issue. Curriculum cannot adequately cover nuclear weapons without a robust discussion of deterrence. Deterrence is an important aspect of any debate related to nuclear weapons.As a final thought on the implications of this research, it is important to understand that a well-rounded education can enhance one’s overall knowledge and can potentially create a better thought leader. Simply put, practitioners can benefit from listening to various points of view. Therefore, even though courses are taught with a negative or positive bias, this does not mean that these courses lack merit. This alternate perspective can indeed strengthen the nuclear enterprise by developing academic diversity, with employees familiar with many competing opinions.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- The education that led to this self-funded research was funded by the U.S. Air Force’s distance learning education program (Mihalik, 2018; Sands, 2017) in response to an increased need for critical thinking in the nuclear enterprise in a period of global uncertainty (Bittick, 2019), (Sands, 2018), (Nakatani, 2018), (Sands 2016), and (Sands 2018). This manuscript comprises the fourth publication following (Kuklinski 2020) and (Hall 2020) and (Dmytryszyn 2020). The APC was funded by the program.

Conflicts of Interest

- The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, although the decision to publish the results has been emphasized by the funders.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML