-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Education

p-ISSN: 2162-9463 e-ISSN: 2162-8467

2020; 10(1): 1-12

doi:10.5923/j.edu.20201001.01

The Use of Virtual Learning Environment and the Development of a Customised Framework/Model for Teaching and Learning Process in Developing Countries

Aaron A. R. Nwabude , Francisca Nonyelum Ogwueleka , Martin Irhebhude

Department of Computer Science, Nigerian Defence Academy, Ribadu, Kaduna, Nigeria

Correspondence to: Aaron A. R. Nwabude , Department of Computer Science, Nigerian Defence Academy, Ribadu, Kaduna, Nigeria.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2020 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

The use of virtual learning environment for teaching and learning provision is one of the concepts that are changing the frontier of knowledge acquisition in today’s educational arena. The flexibility of online learning space can offer developing countries great opportunities in supporting varied learning methodologies. However, it appears that most virtual learning environment framework/models already in use today are not always easily accessible by the students and lecturers who are supposed to use them due to some constrained factors. In such a constrained resource setting, access and use of some of these software platforms for the development of education are limited. This is due primarily to the intractable problem of infrastructural, technological (including internet), educational policy formation, environmental and economic factors limiting progress. In this paper, we examine virtual learning environment framework/models that are already in use by various tertiary institutions across the globe. As we do this, we have come up with amalgamated framework from two existing frameworks, and then developed a model called NDA Customised VLE System Model (CVLESM) for a customised VLE platform in Nigeria. The proposed model has a four level platform: the teacher, student, institution admin and the customised application software. Users will have the option of interacting with the institution’s network systems through the university portal, but also with proposed ‘Mobile App’, which might be downloaded onto any internet connected device including mobile phones. This is novel in this study.

Keywords: Virtual Learning Environment (VLE), Information and Learning Technology (ILT), Framework/Model, Unified Modelling Language (UML), Technology –Mediated Strategies for Teaching and Learning

Cite this paper: Aaron A. R. Nwabude , Francisca Nonyelum Ogwueleka , Martin Irhebhude , The Use of Virtual Learning Environment and the Development of a Customised Framework/Model for Teaching and Learning Process in Developing Countries, Education, Vol. 10 No. 1, 2020, pp. 1-12. doi: 10.5923/j.edu.20201001.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Information and Learning technology (ILT) as part of Information System (IS) is like any other branch of computer science field emphasising functionality over design [1] and characterised by its own research models and frameworks that cover extensive topics and academic concerns. It appears that many institutions across the world have continued to make some investments on the implementation of VLE in order to support teaching and learning and leverage education for all. However, there appears a lacuna on a practical-based VLE framework that incorporates organisational preparedness, technology-mediated and pedagogically standardised VLE framework to manage aspects of teaching and learning particularly in the developing countries. The result is generally low achievement of learning goals of the University concerned. Although there has been some reported cases of frameworks within the field in literature [2] nevertheless, some of these reported cases of VLE frameworks appear to lack the major key elements for integrative, cooperative teaching and learning in some parts of the developing world due to certain resource inadequacies, while in others, teachers have failed to locate and manage features embedded within the VLE itself. But more than that are the environmental, economic, technological and infrastructural factors among others prevailing in most developing countries. In Nigeria for example, specific problems regarding e-Learning and the use of VLE generally include the following: lack of technology integration into practice, lack or involvement of highly trained personnel to handle aspects of e-Learning, lack of adequate management and financial input, and curriculum mapping i.e. breaking curriculum and courses into manageable chunks to suit specific e-learning requirements [3], [4]. This is in addition to lack of infrastructure, and organisational involvement. It is not uncommon for Nigerians to use VLE in their studies but these factors appear to present serious challenges. For example, where there is no steady supply of electricity, computer connected network and internet, and lack of collaboration amongst the organisations, the use of the learning platforms can only be a wishful thinking for users). These inadequacies appear to negate appropriate use of VLE platform for mediating and supporting teaching and learning in tertiary institutions particularly in Nigeria. Therefore, this gap in literature necessitated the search for integrated good – practice and customised VLE framework for developing countries which might integrate elements from literature and the case studies to provide integrative pedagogical environment with intrinsic details. This study therefore, makes contribution to the body of knowledge by introducing a simple customised VLE framework/model that has all the trappings of good practice, technology mediated and pedagogically implementable within the tertiary institutional environments in the affected regions. So, based on literatures and case studies conducted in this research, a framework/model for the implementation phase was developed which considers attributes such as Organisational readiness, appropriate contents, appropriate application, implementation of e-learning, behaviours, cognitivism and constructivism as major constructs critical to successful integration into educational system of these countries. Finally, the model considered therefore, has four main attributes including teacher, student, institution’s admin and application software. It is our belief that the proposed CVLESM might be able to mitigate the above challenges through the use of “VLE App” proposed in this study. This App which could be downloaded onto the users’ mobile telephone sets is proposed as a result of inadequate power supply and frequent interruption of network connection to computer application systems. Users might be able to use the CVLESM App to conduct their learning process as long as the users have enough data in their cell phone systems. This is in addition to the institution’s portal where VLE platform is lodged.

1.1. The Virtual Learning Environment (VLE)

- While the field of education has seen the use of digital virtual worlds for several years [5], increased advances in capabilities of educational technology has resulted in massive use of multi-users virtual worlds: this has fed interests in educational application and the use of Virtual Learning Environments (VLEs). Besides, VLE has enabled educational world to sell their products online thus, public and private sector education view students as consumers [6]. Although, virtual learning has the potentials to offer good and distance education comparable to physical classroom situation in the developed environment, some parts of the developing world appear to struggle in harnessing and accessing these potentials to meet the needs of e-learning subscribers in this turbo-charged digital race. Essentially, several frameworks and models have been adopted by stakeholders towards implementing eLearning through the use of computers, technologies and internet. E-learning has been defined by different authors, for example, European Commission defined E-learning as “the use of new multimedia technologies and the Internet to increase learning quality by easing access to facilities and services as well as distant exchanges and collaboration” [7]. Abdad et al, [8] also defined E-learning as any learning that is electronically enabled. Thus, e-learning simply is the use of multimedia, information and communication technologies to extend diverse processes of education to support and enhance teaching and learning in higher institutions across the globe [9]. Conversely we also need to understand what constitutes VLEs. In the following section, we explore the meaning of the word, ‘Virtual Learning Environment’ from the perspective of teaching and learning with a brief history. In 1997, the ‘Indiana University Committee on Classroom use’ defined learning environment as “a physical, intellectual, and psychological environment which facilitates learning through connectivity and community” [10]. Following this definition, the Joint Information Systems Committee (JISC) in July 2000, recommends that the term ‘virtual learning environment’ (‘VLE’) should also refer to ‘the components in which learners and instructors participate in “on-line” interactions of various kinds, including distance on-line learning’ [11]. With these definitions and additions in the minds of computer and technology scientists, software developers, and education managers, comes the realisation that a VLE indeed describes a particular toolset designed for and with instructors and learners in mind. This toolset offers the ability to schedule a range of learning activities and make tools available rather than just managing contents [12]. In other words, a VLE provides necessary tools which might enhance student’s learning experience and also provides flexible environments where students might choose to learn at a time suitable. Broadening our knowledge of a VLE further is the concept as a one stop shop from the European Schoolnet [13] which argues that the evolution of VLE and its success is dependent upon the integration of such components as course outlines, email, conference tools, threaded discussions, home pages, assignments, assessments, feedback tools, multimedia resources, Web publishing, chat and diagnostic tools, file upload with tools for building knowledge and linking administrative information. Underlying all these definitions and concepts are two central meaning: first, virtual learning environment supports social constructivist approach to teaching and learning [14,15, and 16]. Second, it “provides learners with all the facilities and learning opportunities that they experience in a face-to-face teaching situation even with added advantages of flexibility of access to digital discussion, support, resources, and assessment” [17]. Thus, implies that a VLE platform has the capability to increase learners’ tendency to learn, to multitask and to develop social autonomy through added tools and flexible learning environment. It also, provides learner the extended programme beyond the four walls of the classroom anywhere, anytime as long as learner has log-in access to virtual classroom through the Institution’s portal. Although, VLE cannot work on its own except there is a working internet connected to a computer system and both lecturers and students possess the e-skills and knowledge to access, use and interact with it.

2. Material and Methods

- This paper discusses the study in relation to methodology and methods adopted in the current research setting through systems document-led approach, analysis and nature of design. As noted by [18], methodology in itself is the theory of how inquiry should proceed. It explicates the choice made by researcher with regards to processes and methods used including forms of data gathering and techniques of analysis [19]. However, when we look at methodology as a whole, we refer to a constructive framework, a systematic process which provides research design, methods, approaches and strategies used in an investigative study [20]. For example, selection of participants, instruments used, data gathering and data analysis used in this study are all parts of academic practices used in an investigation in order to answer research question [21].In this paper therefore, we present a case study research method that was conducted in order to understand the lecturers and students’ experiences on the uses of VLE in two distinct international environments: the United Kingdom and Nigeria contextually. Case study research method is necessary in this study because it provides in a nutshell, detailed investigation of these experiences and how the experiences are shaped in the study. The study used inductive process (generating theory for testing) rather than deductive (testing theory) as the vehicle of choice. This has therefore, provided opportunity for sequential collection of data which in turn made available evidence and features to address subsequent data collection and analysis. The population in this study includes lecturers and students from 4 higher institutions who participated in the study by filling out survey questions and taking parts in interview and observation exercises across the case study settings. Specifically, the science students from one institution in the UK and the faculty of sciences and Art students from three institutions in Nigeria, including their tutors were chosen as representative mix of participants’ in their subject areas ranging from Computer science, Mathematics, Chemistry and English literature, Engineering, Medicine, Military science and inter-disciplinary studies and Art. The population is comprised of 120 student participants and 4 subject teachers from the UK institution, and 120 undergraduate students and 30 teachers from Nigeria institutions. This brings the total number of participants in this study to 240 students and 34 teaching staff. These participants took part in the study. In terms of sampling strategy, this study adopted a purposive (non-probability) sampling strategy which enabled the researcher to draw participants from predefined groups of participating students and staff within the case study settings. Research instruments used in this study include questionnaire, interview and class observation.

2.1. Research Instrument and Data Collection

- Having reflected on the researcher’s constructivist viewpoint and the drive to achieve subjective reality [22], the study opted for data collection and analysis that includes the following techniques;• Data collection method 1 - Questionnaire • Data collection method 2 - Interviews • Data collection method 3 – Class Observation The process of data collection and analysis followed a sequential approach, meaning that one phase of activity is completed before the next. This ensured that results of analyzed data in one stage became a precursor for, or provided evidence or themes for use in the next stage. Data were collected during the months of September 2014 running through to January 2015 in the first phase, and Oct 2017 up to February 2018 in the second phase.The analysis of data for this study was carried out in sequence, meaning that survey data was completed first; this is then followed by interview and finally the observation data. The survey data once completed was coded and then inputted into SPSS for descriptive analysis while, the interview and observation data were coded but analysed thematically. The descriptive analysis of survey data generates frequency tables, charts and percentages while, the thematic analysis provides themes for identification of features or categories of any reported uses of VLE or problems inherent in its use.

2.2. Outcome from Data Analysis

- Result showed that VLE (Moodle) was fully implemented in two out of the four case study institutions under the study. The other two though, lay claims to possessing VLEs, but only out-sourced for online provisions. In one of the institutions, prior to implementing Moodle VLE platform, the use of another piece of VLE platform called Fronter MLE had been in practice. The institution felt that this new change might enable students to begin to acquire needed personalised skills and therefore develop the experience to integrate VLE into learning even as they progress into higher learning at universities or into work environments. Others felt the need to integrate VLE into their online aspects, hence the implementation within online programme cohorts and not across the wider institutional teaching and learning delivery. So, what is the implication? To achieve the purpose for which VLE is implemented in the first place, both teachers and students in the case study settings need to gain appreciable levels of skills through training from the Moodle expert in order to be able to use the platform interactively? This is paramount considering that it is a new system which requires total cultural change in attitude and practice. However, data from one of the institutions indicated that this sort of training was not implemented and where training was done, some teachers were unable to attend due to other pressing teaching matters. Nevertheless, teachers welcomed the implementation and integration initiatives into the programmes and, having the understanding of the full benefits to both teachers and students. At the same time, teachers’ anxiety also accompanied with feelings of imposition of pressure to use VLE to facilitate subject learning for which they are less confident and competent. Therefore, the general effect is; eroded pedagogical autonomy and disempowerment as teachers are left to decide whether to use it or not, and what level of usage to make of the new VLE in their teaching and student learning. As a result, the use was less integrative inside the classroom, but more as a repository system. This means that the development of skills by the students are limited to what teachers can be able to do with VLE, and in this case usage is more on the assignment and information retrieval outside the campus than inside the institutions’ environments. Thus presents further implication on the general skills development of the students. So the question is; how can teachers be convinced that VLE enhances teaching and students’ learning experience.Following the analysis of data generated from the experiences of VLE users and the results of related studies, a new modified customised VLE framework was reconstructed from two existing and already in use frameworks. This gave rise for the development of a model called NDA VLE Customised System Model (CVLESM), with four level platforms: the teacher, student, institution’s admin and application software interacting with the institution’s network systems VLE portal, but also with proposed Mobile App. which might be downloaded onto any internet connected device including mobile phones. This is novel in this study.

2.3. Existing VLE (e-Learning) Frameworks

- This study explores aspects of five existing conversational online models or frameworks within the social constructivist computer science domain as developed and inspired by various authors. However, to be clear of any ambiguity, we describe briefly the meaning of model and framework as used in this study. Most often times, model and framework are used interchangeably, however, model as defined by literature is “an abstract representation of the real world” [23,24], whereas “framework is a re-usable design of all or part of a system which is represented by set of abstract classes and the way their instances interact” or “as the skeleton of an application that can be customised by an application developer” [25]. The difference between the two however, is that; a model is simply a process that represents an existing substance, whereas framework describes what needs to be done, stages and what to consider in the process at each stages. Thus a framework can be tailored in this circumstance to suit the implementation of online learning platform, such as customised VLE system which offers full learning environment to all learners including distance learners through web technology [26]. In the section below, we describe some of the existing e-learning frameworks in order to arrive at a new customised VLE framework for the use of tertiary institutions in the developing countries.

2.4. The Selected Existing Frameworks

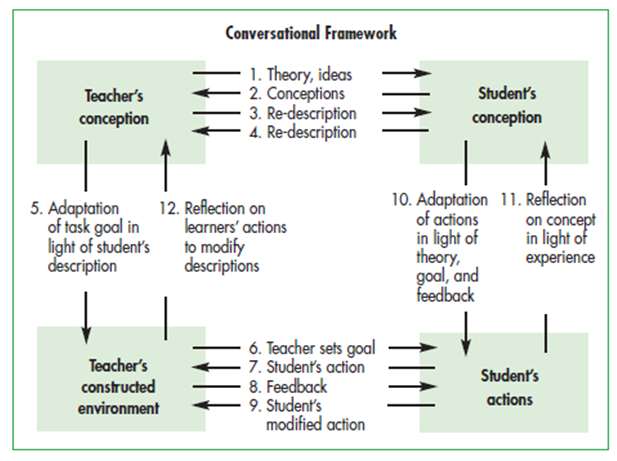

- In order to discuss some of the existing frameworks for online learning in this study, we looked at the following; [27] Conversational Model, [28] Framework for E-Learning as a Tool for Knowledge Management, [29] five stage model of online learning, [26] Design Framework for Online Learning Environments, and [30] Khan’s Octagonal Framework for blended learning. These five existing frameworks were selected as yard sticks to examine and compare what features they contain and how they are related in the design. So we looked at them to enable the development of suitable customized VLE online learning framework and model for the Nigerian higher education institutions (HEIs). However, in this paper, we limit our discussions only to two aspects of the frameworks. The criteria used in selecting the two frameworks were based upon the aforementioned problems which include technological, organisational and pedagogical to mention a few. In this study, technological considers methods of providing teaching and learning in a constructive ways, while organisational looks at the management issues, academic administration, learner services, and staff support. Pedagogical canters around curriculum content analysis, learner needs and learning objectives. The inclusion of the above in one platform ensures that the new customised framework is equipped with the missing attributes and tools for e-Learning delivery which are lacking in each of the two selected frameworks. These two include; Laurillard’s conversational framework/model, and [26] frameworks for Online Learning Environments. The conversational framework/model [31] (Figure, 1); principally draws from Pask and Scott’s conversation theory to explain dialogue as an important and effective construct in academic learning environments. Laurillard contends that academic learning is largely influenced by acquisition of complex concepts and conceptual differences which might not easily be achieved in a face-to-face traditional learning environment, but in a two-way-dialogue between teacher and student at the level of conceptions. According to Laurillard, this dialogue becomes the centrality of any meaningful academic learning process which is supported by the creation of interactive ‘micro-worlds’ (learning activities) [32], enabling students to further engage in activities formulated through discussion. In other words, Laurillard’s conversational model emphasises that the adapted activities should be based on the conceptual dialogue between the teacher and the learner and not necessarily on pre-set idea. The key aspect for this model therefore, is the categorisation of interactions as ‘a constant process of reflection and negotiation between students and lecturers’ in online learning environment [33]. The diagram (Figure 1); presents conversational framework, depicting teacher’s conception, student’s conception, teacher’s constructed environment, and student’s action following teacher’s feedback.The processes underlying conversation framework are classified into four stages covering: 1. Discursive phase: when concepts are introduced by teacher, both teacher and learner enters into dialogue and collaboration in order to understand the concept.2. Interactive phase: tasks are formulated with new concepts; learners interact with tasks and receive feedback on their performance from their teacher.3. Adaptive phase: knowledge is constructed as learners put the new tasks into practice based on knowledge gained in order to adapt appropriately. 4. Reflective phase: learners now reflect on each stage to further help to adjust their thinking following constant reflection.

| Figure 1. Conversational Model [31] |

2.5. Design Frameworks for Online Learning Environments

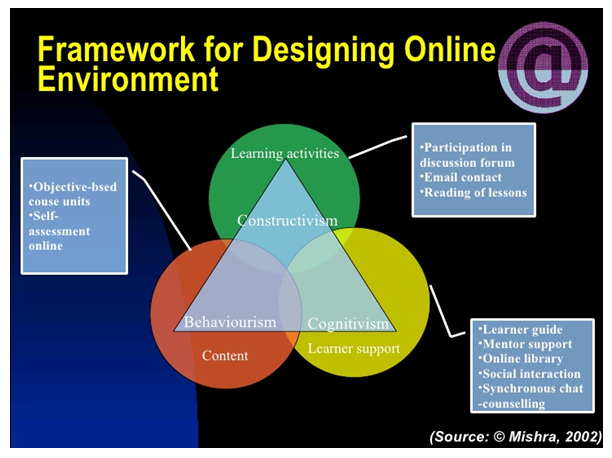

- Another interesting framework for online learning which has actually been used in the design of course work for the Post Graduate programme is presented by [26]. Mishra explored three schools of thought in order to provide guidance for instructional practice. This design framework which is meant to create online learning environment is typically composed of three pedagogical elements: constructivism, behaviourism, and cognitivism: (Figure 2).

| Figure 2. Design Frameworks for Online Learning Environments [26] |

2.6. Framework for E-Learning as a Tool for Knowledge Management

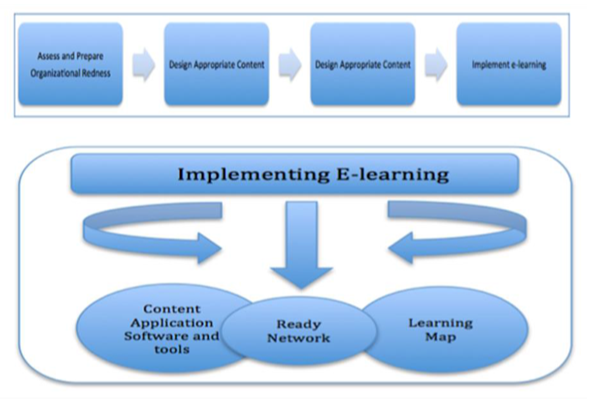

- In this framework, [28] highlights key features of online teaching and learning delivery including factors which needs to be considered such as pedagogical, technical and organisational prior to embarking on e-learning education.Figure 3 presents e-learning value chain which represents different phases that might be applied to VLE platform implementation in tertiary institutions of learning. This framework demonstrates determining factors in organisational strategic decision making requirements, including key stages to follow before going online [28].

| Figure 3. Framework for E-Learning as a Tool for Knowledge Management [28] |

2.7. Theory: Weaknesses of the Frameworks in Prior Research

- Existing e-learning/VLE systems frameworks considered in this study (e.g. Conversational framework, Design Framework for Online learning Environments, and Framework for eLearning as a Tool for Knowledge Management, appears to have not considered some of the difficulties that might possibly occur while developing e-learning education systems in developing countries.As indicated above, some of the difficulties that might occur while developing e-Learning education in developing countries include:• Lack of trained ICT skill personnel to handle ICT integration into studies for effective e-Learning education. • Lack of adequate management and financial support from the government and institutions to pursue e-Learning implementations [4].• Lack of collaboration between the constituted authority and the stake holders in education.• Lack of adequate infrastructure to enable and empower academics, institutions and system developers towards the development of e-Learning system. • In ability of the academics to redesign courses and programmes to suit specific e-learning requirements [3].• Lack of foresight and understanding relating to issues of technology and pedagogy, and how teaching and learning have developed over the century.• Inadequate support systems for teachers to improve technological competence thus eliminate possible variability in teachers’ uses of tools in the classroom.These and others form part of the difficulties inherent in the development of e-Learning culture and the design of VLE for online education in developing countries.Perhaps, the striking assumption by the authors in this paper might be that the developing nations should be able to develop their own VLE frameworks, otherwise learn to use what frameworks there are that have been developed already. Although, it is not certain how much software developers in the developed economy know about the problems of infrastructural, environmental, economic and inadequate educational policies militating against real development of e-learning systems of education in the developing world. According to literature, infrastructural development requires a scale of investment, and this is one of the greatest challenges facing African continent today [39]. Although, VLE framework has been studied as a construct in information and learning technology research, customisable VLE framework has not been simultaneously studied alongside the existing information and learning technology frameworks by other researches. This paper perhaps might be able to solve this problem by constructing a usable, customisable VLE framework/model for use by the developing countries, hence the proposed framework in the section following.

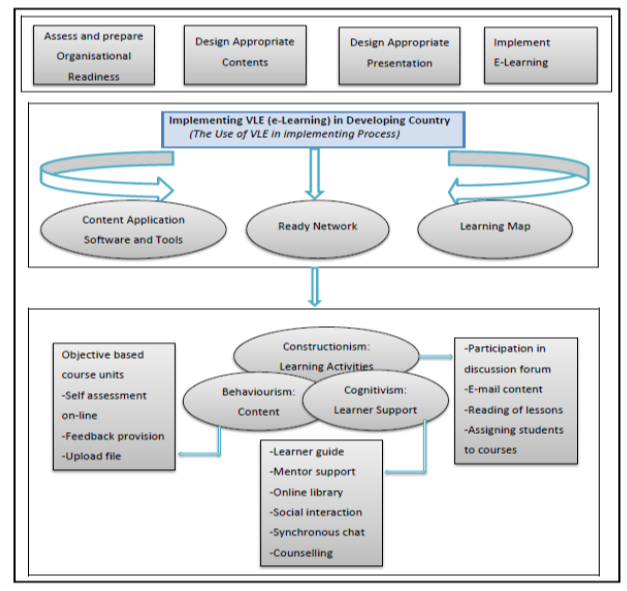

3. Results: Proposed Framework

- Having explored some of the various frameworks and models inherent in the development and implementation of a VLE in HEIs in the developed world generally, and observing the commonality of rudiments amongst them; this paper provides a simple but workable constructivist framework for the implementation of quality and adaptable VLE system in Nigeria. This is done with understanding of the prevailing circumstances and level of infrastructural and technological development, and their impact on the African continent especially in Nigeria. The proposed framework discussed below is an amalgamated and modified system by the current researcher from two frameworks developed originally by [28], and [26] studies. We modified the frameworks thereby, making it relevance to a customised VLE framework that seems plausibly usable in the developing world such as Nigeria. It incorporates elements from the constructivist understanding of the 21st century knowledge constructs, while providing access to Educational Organisations (Universities) to first ensure its readiness in embarking on the use of VLE in order to leverage education generally. As indicated earlier, Social Constructivist approach is based on discussion forum and on-line collaboration: thus appears to have different setting from the traditional conversational classroom practice [27]. In the section below, we critique these existing frameworks against their explicit criteria.

3.1. Critiquing Existing Frameworks/Models against Explicit Criteria

- The afore-mentioned frameworks might offer academic staff a podium to look into technology driven educational and instructional system designs for the good old teaching and learning approaches however, there are concerns. Although, we need to bear in mind that no one framework can fit all purposes at all times. In this section, we critique the frameworks against its explicit starting with the conversational framework/model.The ‘conversational model/framework’ is conceived with the idea that learning can only be a continuous iterative dialogue between teacher and student: thus reveals conceptions and variations between participants [40]. This framework made us to understand that information could not be passed without the inclusion of discussion, interaction, adaptation and reflection; however, this aspect might be considered idealistic in HEI and advanced studies because the teacher might not be able to interact with individual learner in a large class situation. Although, dialogue as key to academic learning and constant feedback might enable learning substantially, it appears truly unrealistic to apply it as a teaching method. There is also an emphasis on micro-worlds (activities) which is not pre-set in advance but on the basis of dialogue. Finally, the model advocates reflection and feedback as opportunity for teaching and learning process; again, this might not be practicably feasible in a large class situation. In respect to ‘Framework for E-Learning as a tool for knowledge management’, the full descriptive essentials in learning process appear to have been embodied in the framework nevertheless; it is difficult to follow in real practical terms by learning organisation. Secondly, the interactive pedagogical phases of the framework appear to lack intrinsic details with adequate involvement of team players and stakeholders in the organisation. This renders it unsuitable for other projects. For ‘Gilly Salmon’s five stage model (Salmon, 2004); the model provides opportunity for different learners to develop according to where they are in their learning process. However, teachers’ support at various stages becomes a prerequisite element in the model since the development of students learning along the philosophy of the model is linked to programme design and methodological constructs. With this understanding therefore, teacher’s constant contribution becomes fundamental for the success of the students. The model appears to dominate and stifle the development of professional practice because of difficulties perceived when [41] used it as a template for an e-moderating training course which failed to account for individual learning styles as a result of its rigid design application. Lastly, there is little guidance to measure appropriate levels of socialisation with the model [42]. The key limitations in ‘Mishra’s design framework for online learning environments’ include lack of comprehensiveness regarding technical and institutional considerations which ultimately should naturally be at the center of online learning. Secondly, the embedded features for inclusion onto the VLE for specific course(s) appear to differ from one subject to another. In the case of ‘Khan’s octagonal framework’, the system addresses the design, development and delivery, evaluation, web-based hybrid instruction stages with guidance; however, it does not prescribe any specific process for the development of educational technology environment [43,44]. Although, it provides valuable guidance for institutions ready to migrate to blended environment nevertheless, fails to address the infrastructural needs in a multi campus environment [43] as well as the developing world. Finally, the framework appears to concentrate efforts only on e-learning of blended environment but lacks the planning tool for the development of vocational learning pedagogy, preferring rather the use of different dimensions to organise and describe principles governing course designs [45]. In general, the five existing frameworks can be said to have lacked comprehensive guidelines to provide answers for total implementation of the kind of VLE system that might enhance online education and learning at higher education institutions especially HEIs in the developing world such as Nigeria; a gap that appears to be filled by the current study. The outcome therefore, is a simple but practical framework with key elements for the implementation of VLE that has all the trappings to mitigate some of the existing problems militating against the effective use of e-Learning in Nigeria (Figure 4).

3.2. The New Customised VLE Framework

- The new framework for the development of customised VLE system proposed in this paper was constructed through a varied intrinsic interpretivist case study research and related literatures in the field. The aim of the framework/model was to provide through modified already in-use online contexts, a good customised e-learning environment framework for the use of higher institutions (His) in the developing countries. The components of the framework are identified and the constructs concerning the framework are presented in this section as figure 4, showing VLE customised framework for tertiary institutions in Nigeria.

| Figure 4. A Customised VLE framework for the tertiary institutions in Nigeria |

3.3. Brief Discussion of the named Constructs

- Organisational preparedness: this is an important attribute in designing any pedagogically meaningful e-learning education because organisations fail when they integrate e-learning solutions without first analysing their readiness. This phase therefore, involves the combination of efforts from various stakeholders together with the technical support team to think about the exact needs of the organisation, in terms of staff competence, cost, and available infrastructures e.g., power supply, internet and broadband technology, security of persons and environment, and technology policy update.In order to develop appropriate contents, the pedagogical (instructional) uses of the new methods are considered and this bring together the analysis of appropriate contents in line with the needs of the learners, together with the objective of ensuring the success of VLE implementation is achieved through personal development.Another important aspect of the framework is the development of appropriate presentation tools to successfully engage learners’ cognitive skills with natural and technologically composed demeanour. This includes techniques to share knowledge through conveyance of complex materials directly to learners in a smart structured, analytic, conversational presentation using flexible content sharing platform such as online presentation (e.g. Apache OpenOffie’s Impress.E-learning Implementation strategies involves a number of steps as indicated earlier; readiness, making a business case, overcoming eLearning barriers, deciding whether to build or to buy, and finally choosing an eLearning partners to share the brunt. The initial step is the review and analysis process which is also known as the diagnostic stage. This is the critical decision making process which leads to proper plan and design, and choosing user’s need requirements. This phase also incorporates cost-effectiveness and sustainability process of ensuring that the system can be managed and able to support future generation of learners.Constructivism is the key in many educational reform movements. Piaget’s theory of constructivism is having a wide ranging impact on the way teaching, learning and new knowledge is constructed. It is therefore, not surprising that this paper finds it a suitable underlying theme in the development of customised VLE framework for use in the tertiary institutions in Nigeria. The crux of constructivism is the argument that humans construct knowledge and meaning from their experiences through interaction and constant mediation. However, in discussing the constructivism as a theory of learning, this paper makes connection to connectivism which is a more adequate pedagogy to address learning that occurs outside people and organisation [46]. Although, constructivism is an umbrella of all e-Learning theories including connectivisim and cognitivism [46], it may not address adequately the above learning process which is why we briefly explore the concept of connectivism in this paper. Connectivism or distributed learning practice in massive open online courses (MOOCs) appears a more adequate practice for the digital age [46] Connectivism can be placed as a third generation pedagogy for online education [47,48], after cognitivism and social constructivism. According to [49], “Connectivism provides insight into learning skills and tasks that are needed for learners to flourish in a digital era”. There is therefore, the acknowledgement that individuals rely on learning that lay outside learner’s domain using other social technological networking tools such as the VLE platforms. This presents opportunity for students to interact with one another and make choices about their learning. Hence, the inclusion in the customised framework which provides a clear set of requirements and a yard stick for the measurement of VLE that supports interactive learning processes in the developing countries such as Nigeria. Cognitivism is a theoretical concept for understanding the mind, thought and problem solving of the kind advanced by computationalism [50]. It is therefore a reaction to behaviour. In determining a customised VLE framework for developing countries, we need to understand knowledge “acquisition as a conscious and reasoned thinking process, involving the deliberate use of learning strategies” [51]. This process might help in processing information that might enhance comprehension, learning or retention of information computationally.In respect to learning, behaviourism is the acquisition of new knowledge and skills based on environmental conditions – linking new behaviour to stimulus. It is therefore governed by infinite set of physical laws, i.e. knowledge as a consequence set of repeated actions/ behaviour. When human comes in contact with computer system, the constant interaction between them results in some kind of stimulus which produces new sets of behaviour that might be organised into new knowledge, thus, the incorporation into the customisable framework. Finally, we argue that the above framework might not be the ideal VLE framework after all, but certainly provides contents which might deliver effective students centred teaching, leading to effective students’ engagement and learning experience in Nigeria higher institutions. It will therefore encompass making concepts explicit, encouraging peer and group collaboration, discussion and reflection on the teaching processes and pedagogical uses of a VLE. It therefore encompasses making concepts explicit, encouraging peer and group collaboration, discussion and reflection on the teaching processes and pedagogical uses of a VLE. Teachers, tutors, and institutions however, need to find appropriate medium to boost competence through training of teachers on the new instructional technology for better teaching and learning, incorporating concepts or values that provide forum for students to contextualise new knowledge. In this respect, this paper fills considerable lacunae in knowledge and strategic guidelines hence, the novelty of this work.

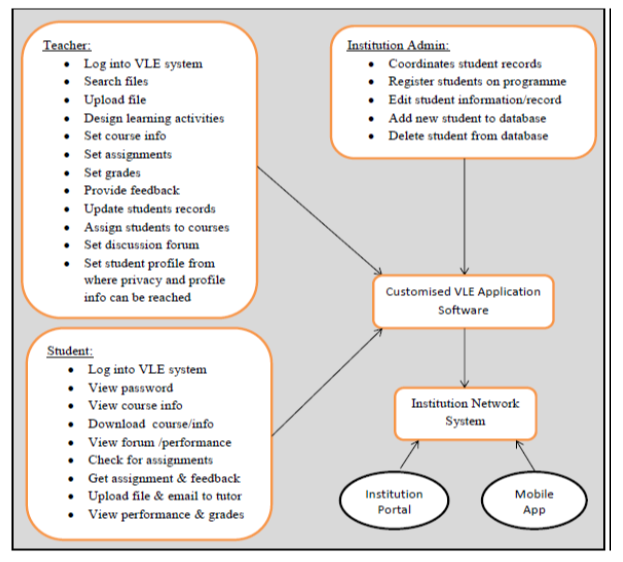

4. Developing the Proposed VLE Model

- Based on the frameworks discussed, literature reviewed, and research question, we propose a new customised VLE model as major constructs to suit the identified learning environment. This new model incorporates those inadequacies found in the existing VLE frameworks as currently being used in the developed environment. In order to achieve this goal technically, we explore widely adopted object-oriented modelling language: ‘Unified Modelling Language’ (UML) abstraction with standard set of diagrams and processes. This has enabled us to propose a customisable VLE model for use by HEIs in the developing countries. The UML diagrams deployed here include: Use case, Class and State diagrams, Sequence, Deployment, and Component diagrams (Figures 5).

| Figure 5. Key UML Diagrams used in this study |

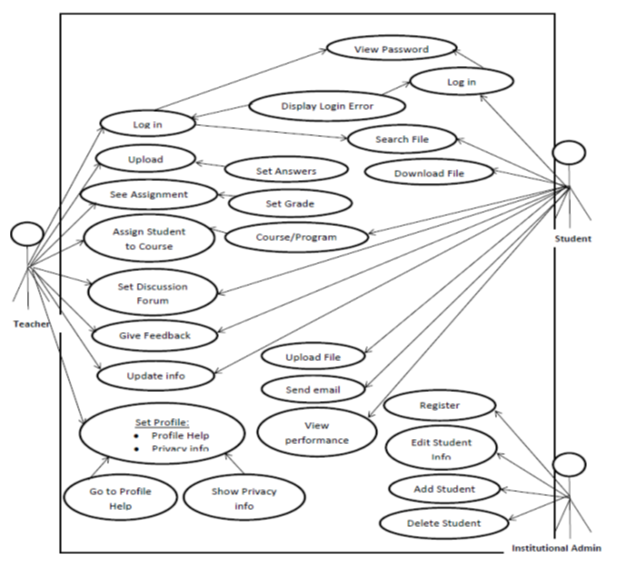

4.1. Developing a Use Case

- In order to assist in the development of the customised VLE model for this study, we first of all, developed a ‘use case diagram’ which provides the key players in the system (Figure 6).

| Figure 6. Key Players at Each Stage of Development & Implementation |

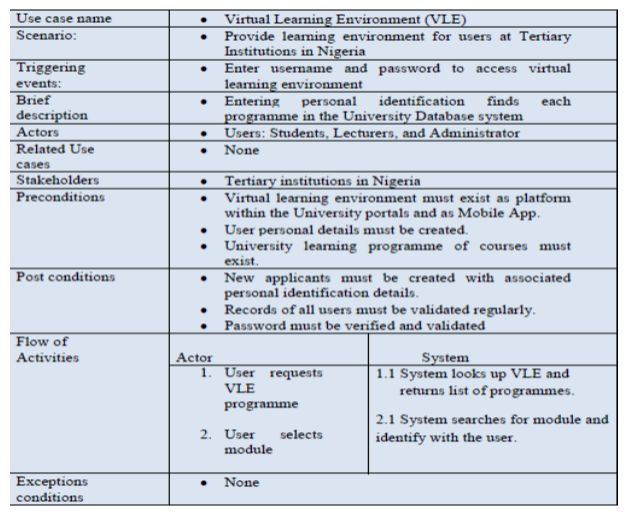

4.2. Use Case Description

- In order to obtain the external view of the use case scenario, we provide a description of its function. In this use case description therefore, we place emphasis on the interaction with the virtual learning application and also the preconditioned elements which reveal what existing objects that must exist before the use case can perform its functions normally (Figure 7).

| Figure 7. Use case description |

4.3. Developing the NDA Customised VLE Model

- The Nigerian Defence Academy (NDA) Customised VLE System Model (CVLESM) for developing countries was constructed by the researcher based on the framework, literatures and research question proposed by this study. The aim of the model was to provide enhanced VLE online environment for teaching and learning in the developing countries e.g. Nigeria but, also as a resource for future research (Figure 8).

| Figure 8. NDA Customised VLE System Model (CVLESM), for Developing Countries |

5. Discussion: Expected Contribution

- This paper presents amalgamated and customised VLE usability framework that embodies constructs such as; Organisational readiness, appropriate contents, appropriate application, implementation of e-learning, behaviourism, cognitivism, and constructivism for use by the universities in the affected region. In the case of the model, elements and constructs considered include; teacher, student, and admin staff. These are the people who are going to use the VLE for learning experience and for management of programmes in the institutions. These users would be interacting with the software application through the institution’s network systems with options of the use of the university portal or executable file downloaded as mobile application (Mobile App) using mobile phones or laptops, etc. It can be said that through our careful decomposition of different frameworks within eLearning portfolio and data derived from use case scenario, a more informative, reach learning that is specific to the customised VLE model (CVLESM) has been developed (Figure 8).

6. Conclusions

- This paper is an attempt to explore current research which is aimed at developing a customised VLE framework (CVLEF) with its attendant model and therefore, reviewed some of the e-learning capabilities in order to develop a good-for -use customised VLE framework for the universities in Nigeria. Consequently, through series of related literatures in the field, this paper finally presents a framework/model for this purpose in order to meet the needs of the tertiary institutions in the developing countries. The framework was purposefully constructed as a guide for online educational implementations consisting of 7 components (see Figure 4). The amalgamated framework further facilitates the development of a model (the NDA CVLESM) also designed for online learning environment. This model has four level structures: teacher, student, institution’s admin, and the customised application software. Each level has its own activities and functions; however, customised application software has additional constructs: institution network system, institution portal and mobile application. We therefore, reiterate that the functional requirements of a given, usable and customisable VLE framework /model for the developing countries such as Nigeria should embody the above framework as devised in this study. We also argue that E-Learning providers’ success would be implicitly dependent upon how they negotiate, interpret and successfully apply techniques and strategies to the constructs that constitute customised VLE framework in this study. However, we suggest that future research be focused on the simulation, testing and evaluation of the framework/model in order to provide eLearning guide for teaching and learning across higher institutions in the developing nations.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML