-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Education

p-ISSN: 2162-9463 e-ISSN: 2162-8467

2019; 9(1): 9-18

doi:10.5923/j.edu.20190901.02

College Students' Knowledge and Attitudes toward the Inclusion of Persons with Disabilities in the University

Turki Alqarni1, Rasheed Algethami2, Abdulaziz Alsolmi3, Essa Adhabi4

1Najran University, Najran, Saudi Arabia

2Taif University, Ta’if, Saudi Arabia

3King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia

4Jazan University, Jazan, Saudi Arabia

Correspondence to: Turki Alqarni, Najran University, Najran, Saudi Arabia.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2019 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Previous studies have indicated a lack of information about the knowledge and perceptions of university students regarding students with disabilities and the attributes, affecting their inclusion in higher education. Thus, the purpose of this study was to investigate the knowledge and attitudes and their relationship towards the inclusion of individuals with disabilities in universities. Additionally, this study determined the differences between college students’ characteristics and the inclusion of persons with disabilities in the university campus. This study effectively promotes the inclusion of disability in the university by focusing on increasing the knowledge and awareness of college students without disabilities. The authors used a descriptive research design in this study, focusing on college students’ knowledge of disability as well as their attitudes toward the inclusion of students with disability at universities. The study implemented at Saint Louis University in Missouri. Graduate and undergraduate (N=12, 853) students were targeted in this study, but only 166 students sufficiently responded to the survey questions. Overall, the main result of this study indicated that higher levels of disability knowledge correlated with higher levels of perceptions towards the inclusion of students with disabilities, but this correlation was not significant.

Keywords: College students, Inclusion, Persons with disabilities

Cite this paper: Turki Alqarni, Rasheed Algethami, Abdulaziz Alsolmi, Essa Adhabi, College Students' Knowledge and Attitudes toward the Inclusion of Persons with Disabilities in the University, Education, Vol. 9 No. 1, 2019, pp. 9-18. doi: 10.5923/j.edu.20190901.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) of 1990 requires schools to provide a Free and Appropriate Education (FAPE) in the Least Restrictive Environment (LRE) for students with disabilities, which results in increasing the inclusion of students with disabilities in elementary and secondary education. This inclusion in elementary and secondary education obviously creates a good expectation that they will be included at the next step, which is the higher education (Wolanin & Steele, 2004). However, only 30% of students with disabilities who graduated from the high school attend postsecondary education classes (Wagner et al., 2005). This lower rate of attending universities and colleges caused by several reasons, one of which is that students with disabilities are afraid to face negative attitudes from their typically developing peers. Marshak and her colleagues (2010) stated that student with a disability "desires to avoid negative social reactions.'Little is known about university students' attitudes toward inclusion of students with disabilities and the factors that positively affect these attitudes. Therefore, this quantitative study will examined these perceptions and explore the factors behind them.

2. The Statement of Purpose

- The main purpose of this study is to investigate the knowledge and attitudes of including individuals with disabilities in universities. Additionally, this study is to examine the relationship between college students’ knowledge and attitudes toward the inclusion of persons with disabilities in the campus. Lastly, this study is to determine the extent of differences between college students’ characteristics and the inclusion of persons with disabilities in the university campus. Research questions:1- What is the college students’ knowledge of disability and their attitudes toward the inclusion of persons with disabilities in the university campus?2- What is the relationship between the college students’ knowledge and their attitudes toward the inclusion of persons with disabilities in the university campus?3- To what extent do demographic variables, including gender, age, levels of education, and ethnicity, relate to college students’ knowledge of disabilities and their attitude toward the inclusion of students with disabilities?

3. Rationale of the Study

- The main aim of this study is to promote the inclusion of disability in the university by focusing on increasing the knowledge and awareness of college students without disabilities. Meyer et al (2012) believed that in order to increase and strengthen inclusion of disability in colleges, students without disabilities we need to be aware and knowledgeable about the accommodations process delivered to students with disabilities in universities. Increasing the university students’ awareness of disability can lead to develop positive perceptions of social inclusion and provide the equal chances for persons with disabilities (Sachs & Schreuer, 2011).

4. Literature Review

- Faculty and staff knowledge of disability in universitiesThe lack of faculty knowledge regarding accommodations is a significant barrier for students with disabilities (Sniatecki, Perry, & Snell, 2015). “Without appropriate knowledge, faculty is ill-prepared to make decisions about how to effectively implement accommodations in their classrooms (Sniatecki et al., 2015, P,260)”. In other words, if instructors lack the essential information in regards to accommodating university students with disabilities, it can be very difficult for them to provide the effective resources and aids that can motivate and support the need of those students with disabilities. Therefore, educating the faculty and staff about the accommodation process of students with disabilities can benefit them to receive the suitable services needed in or out schoolrooms.Sniatecki and his colleagues (2015) conducted a study concentrating on the investigation of attitudes and knowledge of faculty regarding college students with disabilities in universities. They mentioned some barriers negatively affecting college students’ experiences in universities. Firstly, the main barrier facing students with disabilities was the lack of awareness and knowledge regarding the students’ issues in the university. In addition, students with disabilities were discouraged in the university due to the attitudes of faculty and staff towards the disability and accommodations provided to them. Both full and part-time faculty participated in this study, and 123 who completed the survey, which was adapted from a faculty survey created at the University of Oregon (2009) and distributed online.Sniatecki et al (2015) founded out that the majority of participants were not sure regarding the Americans with Disabilities Act whether it relates to SWD, as well as faculty members were not knowledgeable about the attendance rates of SWD compared with peers without disabilities. However, the majority of faculty agreed that the students with disabilities do not attend the postsecondary school alike students without disabilities (Sniatecki et al., 2015).Apart from their shortage of knowledge about disability, the researchers believed faculty are strongly aware of disability, and where to gain support for students with disability as well as the additional on-campus services when working with SWD. In the meantime, they found a lot of disability misconceptions expressed by faculty when working with students with disabilities, thus, they suggested that faculty showed provided with additional information and training to develop their knowledge in regards to students with disabilities and the role of DS center (Sniatecki et al., 2015).Other obstacles can affect the knowledge and accommodation of students with disabilities for faculty members. Bento (1996) pointed out that the informational gabs of faculty’s understanding and knowledge of students with disabilities and their accommodation is the fundamental barrier hindering the accommodation of those with disabilities. In addition, the ethical issues can challenge policy makers, especially those instructors who make specific accommodations for students with disabilities (Bento, 1996). Moreover, this ethical barriers oftentimes happen when the needed accommodation can support, but can be an inappropriate decision for other students in the classroom. The last barriers facing the accommodation of students with disabilities in the university is the attitudinal obstacles, known as faculty belief that those students have to face or overcome their exceptionality (Bento, 1996). The obstacles regarding accommodation knowledge overcame through the professional programs targeted the faculty and staff member in universities.According to a study conducted by Murray et al (2012), this study represented the effectiveness of productive learning u strategies towards promoting college faculty and staff of students with learning disabilities. This program is a training program that influences the project resources in ways developing the organizational modification across the whole university by a website, bi-monthly print materials, and informational videos that developed by the project and widely distributed (Murray et al., 2012). The training program applied to university faculty and staff from DePaul University as well as based on the Cascade training empowerment model, which help participants to develop awareness, knowledge and motivation skills regarding college pupils with disabilities (Murray et al., 2012). The components of the program varied; including Summer Institution Preparation Sessions consisted of five-day summer workshop for faculty, and a separate four-day summer preparation institution for staff, and Supplementary Preparation Tools (Murray et al., 2012). Overall, the training model predicted and gave a strong support for college instructors and staff beliefs and knowledge and the training had greatly positive impact on those beliefs compared to reading books (Murray et al, 2012).College students’ knowledge of disability in universitiesMeyer et al (2012) conducted a study focusing on the attitudes of University students without disabilities towards the academic accommodation procedures of students with Learning Disabilities (LD) and Attention Deficits and Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD). Fourteen thousand students invited through email to take an online survey from two Midwest universities. The main criteria of choosing this population was based on two factors 1) those students had a specific age between the age of 18 and 25 and 2) those students spent their entire university live in the educational intuitions where educational accommodation delivered to university students with disabilities (Meyer et al, 2012).The results mostly showed that college students without disabilities had unbiased and positive attitudes towards the educational accommodation of students with LD and ADHD (Meyer et al., 2012). However, the qualitative results appeared that college students without disabilities intensively engaged with students with LD compared to students with ADD and ADHD (Meyer et al., 2012). Furthermore, the authors believed the poor knowledge of one third of pupils without disabilities related the academic assistance provided to their peers with disabilities. This can be due to the context where college students’ attitudes can be similar to the majority at large and are precisely associated with to their experience and knowledge of individuals with disabilities (Pivik et al., 2002). This study provided some suggestions, which can build and increase the knowledge of disability for college students without disabilities.First, policymakers should efficiently activated the on-campus disability services; in order to increase the knowledge of students with disabilities about deserved accommodation (Meyer et al., 2012). University students’ knowledge about disabilities leads to a positive interaction with their peer students with disabilities even though the public perception makes fences to prevent full acceptance (Loewen & Pollard, 2010).Second, a friendly revolution to raise the knowledge of accommodation in universities, such as committed week concentrating on “Disability Allies/Awareness”, to better distinguish students who do need accommodations (Meyer et al., 2012, P, 180). Comprehensive determinations in college disability education may develop students’ knowledge of their colleagues with disabilities and uphold more inclusive student recognition of colleagues with varying disabilities (Upton, 2002). Finally, it is beneficial for pupils with disabilities to learn the self-advocacy skills in order to be able to seek for their best accommodation and respond to challenges facing them due to the lack of accommodation knowledge expressed by their peers without disabilities (Meyer et al., 2012). Inclusion of Students with Disabilities in Higher EducationPrevious studies, which were few, revealed that the majority of university students have positive attitudes toward inclusion of students with disabilities. In the literature review, there were only 8 research studies (Pousson, 2011; Westling, Kelley, Cain, & Prohn, 2013; Bruder & Mogro-Wilson, 2010; Griffin, Summer, McMillan, Day, & Hodapp, 2012; Meyers & Lester, 2016; May, 2012; Nicole, Agnes, & Wendy, 2015; Gibbons, Cihak, Mynatt, & Wilhoit 2015).Bruder and Mogro-Wilson (2010) studied attitudes of both university students and faculty indicated that the students and faculty report positive attitudes toward inclusion of and interactions with students with disabilities. However, these interactions found to be awkward and limited.Visse (2016) published her honor’s thesis outlining “Students Perceptions of Individuals with Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities (IDD) and the Impact of Inclusion.” Specifically, she examined the impact that the inclusion of students with intellectual and developmental disabilities had on their peers, as well as the perceptions non-disabled students had of students with IDD. Through an online survey, students were asked about their perceptions and if they had been involved with organizations that encourage inclusion. The majority of the students (88%) were female, and the students were aged between 18 and 49. Students ranged from freshman to graduate students and spanned several majors. The study found that most students had a positive perception of people with IDD, and the study attributed it in large part to previous experiences of inclusion (Visse, 2016).Westling, Kelley, Cain, and Prohn (2013) conducted a study that investigated university students’ perceptions toward inclusion of students. They indicated that the participants had positive attitudes toward inclusion of students with disabilities. There was also a significant relationship between participants' previous contact with individuals with disabilities and their attitudes. Those who have previous contact with individuals with disabilities tend to have more positive than those who do not. Furthermore, result showed that students who are knowledgeable about postsecondary education programs have more positive attitudes than students with less knowledge. Finally, the researchers found that found a significant relationship between participant’s gender and positive attitudes toward inclusion. They stated that female university students tended to have positive attitudes toward inclusion. This finding supported a study, which was conducted by Griffin and her colleagues in (2012). They reported female students hold attitudes that are more positive and have higher expectations of students with intellectual disability than male student do. The female students also found to be more interested in interacting with students with intellectual disability.Novo-Corti conducted a study regarding the inclusion of students with disabilities in the university setting. This study cited a definition of inclusion as “the placement and education of students without disabilities in regular education classrooms, along with students without disabilities and of the same age” (Novo-Corti, 2010). The study utilized a survey and sampled 180 students in universities throughout Galicia. Using a Likert-type scale, students responded with their level of agreement or disagreement to a number of statements regarding social norms, attitudes towards inclusion, intention, and perceived control. The study found that the environment of the university played a significant role in increasing students’ perceptions of inclusion of students with disabilities. Specifically, the study noted that social norms were the most important variable to students’ beliefs of inclusion (Novo-Corti, 2010). Pousson (2011) found that attitudes of college students toward other students who have disabilities are different due to the type of disability. In addition, the positive attitudes of the participants became more positive if they currently know students with disabilities. Furthermore, May (2012) found that attitudes of university students who are studying classes with students with disability positively changed.Meyers and Lester (2016) investigated whether taking a disability course on college would positively affect the students’ attitudes toward people with disabilities and found that there was no significant relationship between participants' attitudes and taking a disability class.Gibbons and her colleagues (2015) surveyed 152-university faculty and 499 students about their beliefs and attitudes toward inclusion of students with autism and intellectual disability and found that most of them have positive attitudes toward inclusion. Griffin and her colleagues also reported this finding in (2012). However, Gibbons and her colleagues (2015) emphasized that even though university faculty and students have positive attitudes toward inclusion, they have concerns about the negative effects of inclusion in the classroom. Some of these barriers, noted in a study conducted by Jeanne Bruce in the course of her dissertation. She noted that a lack of preparation for inclusion is a significant barrier to full inclusion (Bruce, 2010).Other studies have been conducted examining perceptions of inclusion of students with disabilities in mainstream classrooms by high school general and special education teachers. The findings of those studies are generally consistent with the college studies, with a minor exception that inclusion in high school settings is more common and accepted (Bruster, 2014).

5. Methodology

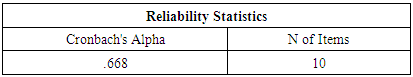

- Research design The investigators in this quantitative study used descriptive research design in order to address the research questions and clearly describe the findings of this study. Creswell (2005) stated the importance of research design as “procedures for collecting, analyzing, and reporting the research in quantitative and qualitative research” (p. 597). A descriptive research design was assigned for this study to investigate college students’ knowledge of disability as well as their attitude toward the inclusion of students with disability at universities. Gall, Borg and Gall (1996) indicated that “descriptive research design is a type of quantitative research that involve making careful description of educational phenomena” (p. 374). In addition, Leedy & Ormrod (2016) stated that “Descriptive research examines a situation as it is” (p. 136).Variable of the studyThe independent variable is the college students’ knowledge of persons with disabilities in the university and demographic variables, such as gender, age, levels of education, and ethnicity.The dependent variable is the attitudes toward the inclusion of persons with disabilities. Site and PopulationThe researchers conducted this study at Saint Louis University in Missouri. Saint Louis University is a Roman Catholic and private university consisted of various graduate and undergraduate majors. It is however open to all students with other faiths. It was found in 1818 and recently have celebrated 200 years of its establishment with a National University, 94 is ranking of US best colleges (US News & World Report, 2018). It also has another campus located in Madrid, Spain. The study targeted graduate and undergraduate degree seeking with a population (N=12, 853) students. The authors used a convenience sample method in this study due to implementing an online questionnaire. According to the population, the sample size (n=266) students was needed to be able to generalize the results over the entire population. However, after cleaning up incomplete data, only 166 students who sufficiently responded to the questions proposed in the survey. Instrumentation The study instrument used to collect the data was an online survey adapted from a previous survey. For the purpose of this research, the researchers selected three sections of this online survey in the study. The first section of the questionnaire was representing the demographic information including gender, levels of education, ethnicity, and age. The second section of the questionnaire was revealing the college students’ knowledge toward the inclusion of students with disabilities in the university. This section provided 10 questions followed by 5 points-likert scales ranging from strongly agree - strongly disagree. The attitudes of inclusion was the third section of this questionnaire also consisted of 10 questions followed by 5 points-likert scales ranging from strongly agree to strongly disagree. Validity and ReliabilityThe mentioned survey gained its validity from notable scholars and professors in the school of education at Saint Louis University. However, it had an acceptable reliability (internal consistency) based on the Cronbach’s alpha (α = .668).

Data collection After receiving the IRB approval, the researchers contacted the faculty of various departments of Saint Louis University to distribute the questionnaire via emails with a letter of recruitment forwarded to their students. However, due to the lack of participants taking the survey, the researchers requested IRB amendments to increase the numbers of participants gained by recruiting more students from Saudi Arabian Students Association at Saint Louis University. Incentives were also employed to increase the participants by using ten random withdrawals of $5 Starbucks eGift Cards. After cleaning up the data, researchers imported the data to SPSS for analysis.

Data collection After receiving the IRB approval, the researchers contacted the faculty of various departments of Saint Louis University to distribute the questionnaire via emails with a letter of recruitment forwarded to their students. However, due to the lack of participants taking the survey, the researchers requested IRB amendments to increase the numbers of participants gained by recruiting more students from Saudi Arabian Students Association at Saint Louis University. Incentives were also employed to increase the participants by using ten random withdrawals of $5 Starbucks eGift Cards. After cleaning up the data, researchers imported the data to SPSS for analysis. 6. Data Analysis

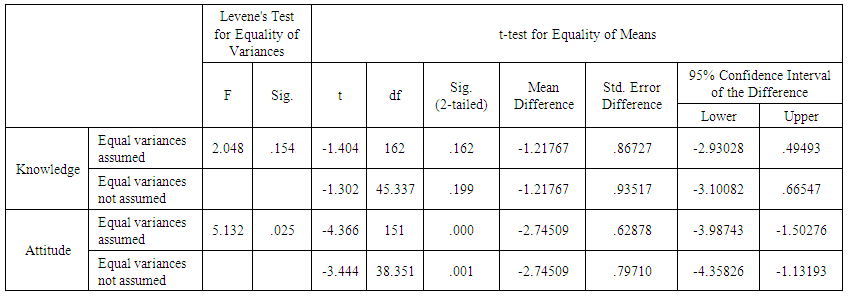

- In this study, the authors used descriptive statistical analysis to answer the first question, which tended to measure university students’ knowledge and their attitudes toward inclusion of students with disabilities. Secondly, in order to identify any possible relationships between university students’ knowledge of disability and their attitudes toward inclusion of students with disabilities, the authors had to indicate correlation coefficient. Finally, they used one-way between groups ANOVA with post-hoc tests and T-tests to examine the effects of independent variables (the demographic variables) on the dependent variables, which were university students’ knowledge and their attitudes toward inclusion of students with disabilities.

7. Results

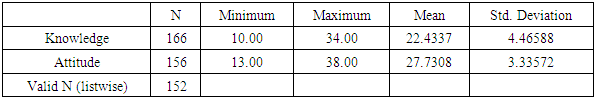

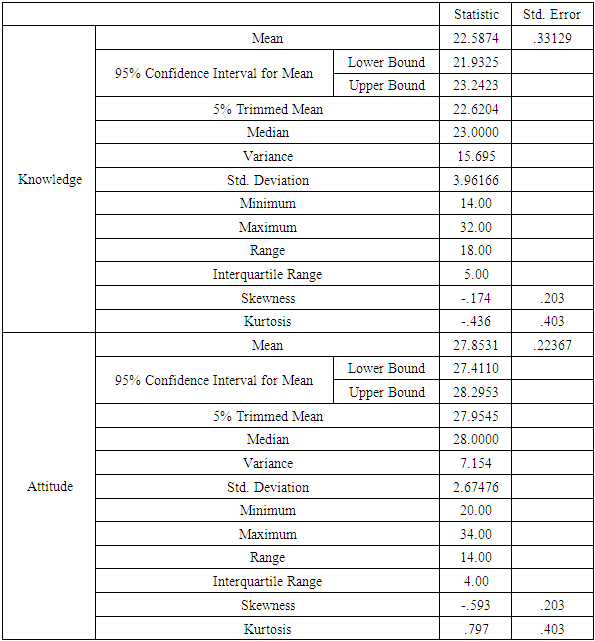

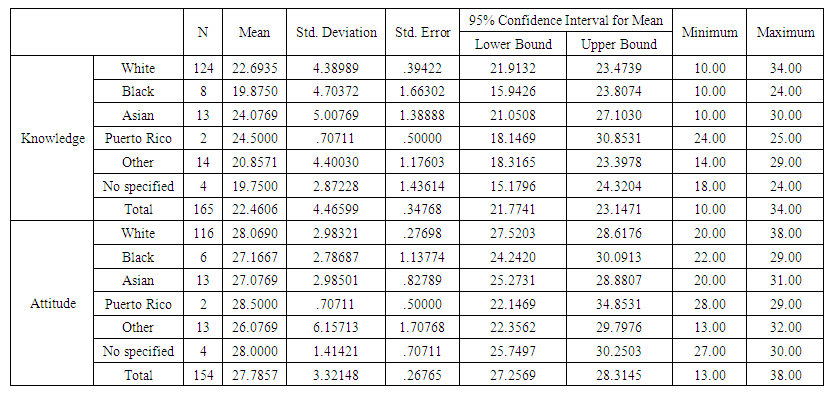

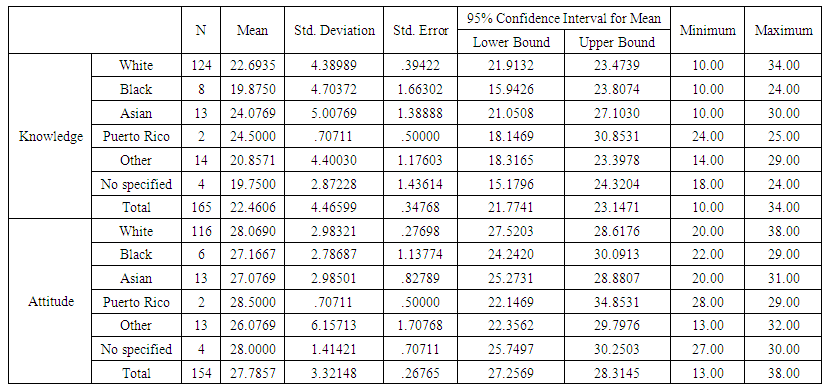

- Level of knowledge and attitudeKnowledge of disability scores ranged from 10 to 34, with an average of 22.43 (SD = 4.47). Attitude towards inclusion of students with disabilities at the university level scores ranged from 13 to 34, with an average of 27.73 (SD = 3.34). A closer examination of the variables indicated there were several outliers on each variable. More specifically, using the 1.5 * interquartile range rule, five outliers were identified on the knowledge variable and four on the attitude variable. After removing the outliers, skewness and kurtosis estimates for both variables were within an absolute value of 2, indicating that each was approximately normally distributed. (See Table: 1).

|

|

|

|

| Table 6. Independent Samples Test |

| Table 7. Descriptive |

| Table 8. Descriptive |

8. Discussion, Limitations, and Implications

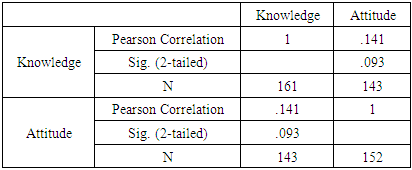

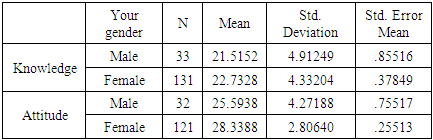

- DiscussionThe focus of this study was three-fold. The first goal was to research the knowledge and attitudes regarding including individuals with disabilities in universities. The second goal was to examine the relationship between college students’ knowledge and attitudes toward the inclusion of persons with disabilities in the campus. The third goal was to determine the extent of the differences between college students’ characteristics and the inclusion of persons with disabilities in the university campus. This section presents the findings of the research and discusses their consistency with the most recent research found in the literature. It will also provide an overview of the implications for students with disabilities in the college setting and implications for future research. For the first question, this study tested knowledge of disability on a score of 10 to 34, and found student participants had an average score of 22.43, indicating that some students have a knowledge of disabilities, but not all students had a high knowledge of even general disabilities. Of the current research that was published, the majority has used knowledge of disabilities as a variable and has not tested for it separately. The findings that knowledge of disabilities were in the middle of the range are in line with another study that found students generally had unbiased knowledge of disabilities but one third did not know about assistance for disabilities in higher education (Meyer et al., 2012).Next, attitudes towards inclusion of student with disabilities at the university level were scored from 13 to 34 with an average of 27.73, indicating generally more positive attitudes. The findings of this study that students in general have a positive attitude towards the inclusion of students with disabilities in the college setting are consistent with current research, specifically, as mentioned above; it is in line with findings from Meyer et al. (2012). There are other studies reporting similar findings of positive attitudes towards students with disabilities in the university setting (Westling, Kelley, Cain, & Prohn, 2013; Pousson, 2011; Novo-Corti, 2010). However, the current findings are inconsistent with the findings of Gibbons, et. al. (2015) that reported concerns by students of the negative effects of inclusion in the classroom. The past research linked findings regarding attitudes towards inclusion of students with disabilities to the students’ self-reported knowledge in their studies. This is somewhat consistent with the relationship found between knowledge and attitude in the current study. There was a trend towards a positive correlation between the two variables, although not statistically significant. More research will need to be conducted to determine if this relationship is present in a larger population.For the second question, this study focused on the relationship between students’ knowledge of disabilities and their attitudes towards inclusion. The past research linked findings regarding attitudes towards inclusion of students with disabilities to the students’ self-reported knowledge in their studies. This is somewhat consistent with the relationship found between knowledge and attitude in the current study. There was a trend towards a positive correlation between the two variables, although not statistically significant. This finding is consistent with current literature, specifically the study Meyer, et. al., conducted in 2010, noting the positive correlation between a student’s experience and knowledge of individuals with disabilities, and their attitudes towards inclusion. The findings were also consistent with the findings of the study conducted by Westling, Kelley, Cain, and Prohn (2013), and the inferences of Visse’s study, which linked positive attitudes of inclusion to former experiences with inclusion. More research will need to be conducted to determine if this relationship is present in a larger population. For the third question, the study looked at differences in knowledge and attitudes related to gender and race. The study did not find a significant difference between knowledge of disabilities between males and females, indicating that gender was not a key factor in knowledge. However, this study found that males and females differed in their attitudes, with females showing more positive attitudes than males. This finding regarding gender is consistent with current literature, specifically the study conducted by Griffin in 2012 that found that female students had more positive attitudes towards inclusion than their male peers, and that female students had more interactions with students with disabilities. Regarding race, there were no significant differences in knowledge, indicating that Whites, Blacks, Asians, Puerto Ricans, and those categorized as “other” showed similar levels of knowledge about disabilities. In addition, the one-way ANOVA comparing attitudes across racial groups showed that they also did not differ, indicating similar levels of attitudes between the different racial categories. Undergraduate [freshman, sophomore, junior, senior], graduate, and professional students were all included in the sample group, yet the research conducted did not find any statistical significance between the level of education and knowledge of disabilities. The level of education did indicate statistical significant regarding attitudes towards education, such that professional students scored significantly lower than all other levels, except freshman. The attitudes of professional students towards inclusion of students with disabilities was not significantly different from freshman attitudes of inclusion. No other study conducted looked specifically at level of education in the college setting as an indicator, so these findings are still exploratory and future studies are needed to replicate the findings.Limitations and ImplicationsMeasurements: The two variables in this study [knowledge and attitudes] were linear. As such, the relationship between the two was not strongly measured. There are also additional variables that could affect students’ attitudes towards inclusion, including if they themselves had any disability, if they had a close family member or friend with a disability, or if they had ever taken a class with a student with a disability. Because these variables were not explored in the current study, the interpretation of the results is difficult because it is not clear whether gender and education levels were key determinants in attitude differences, or if there was another variable acting in tandem. Sample size: This study was conducted among college students in a small, private university, in the Midwest of the United States. Further research should be conducted using a larger sample size from both public and private universities, at institutions across the United States. Increasing the sample size will produce a larger data sample and increase the power, reliability, and validity of the findings. It is also important to include diverse samples in order to ensure the generalizability of the findings.

9. Conclusions

- The study provided meaningful outcomes, which can promote the academic and social awareness of disability in higher education. Although the study appeared the correlation between the knowledge and perception of college students with disabilities in the university, this did not sufficiently display the reality of this correlation between the knowledge and perceptions of inclusion. There were also significant differences of disability knowledge and inclusion among the demographic variables, including gender, ethnicity, level of study and age. Further researches need to be implemented on college students’ knowledge and perceptions of a specific type of disabilities; as each disability exhibits different characteristics and needs in higher education. In other words, college students with learning disabilities need special accommodations that can be different from students with intellectual disabilities. Therefore, educating students without disabilities about various types of disability may help them deal with their classmates with disabilities in the university. For further research of this area, it is important to include issues of interpersonal relations of college students with their peers with disabilities within the university community, the issues of participants' communication culture in the educational process in inclusive higher education.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML