-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Education

p-ISSN: 2162-9463 e-ISSN: 2162-8467

2019; 9(1): 1-8

doi:10.5923/j.edu.20190901.01

Interventions to Support the Development of Spelling Knowledge and Strategies for Children with Dyslexia

Nathalie Chapleau, Kathy Beaupré-Boivin

Department d’Éducation et de Formation Spécialisées, Université du Québec à Montréal, Montréal, Canada

Correspondence to: Nathalie Chapleau, Department d’Éducation et de Formation Spécialisées, Université du Québec à Montréal, Montréal, Canada.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2019 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Learning to spell is a challenge for all beginning writers. For children with dyslexia, in particular, phonological and orthographic deficits are the cause of spelling errors that persist despite classroom instruction. The goal of the present study was to examine the effects of rehabilitation interventions on the development of spelling knowledge and strategies in 12 children with dyslexia aged between 10 and 12 years whose mother tongue is french. An AB1A / AB2A single-case design with replication across participants was used. During the two intervention phases of six weeks each, participants received remedial interventions focused on their deficits (B1) followed by compensatory interventions aimed at developing their abilities (B2). Results indicated that both types of interventions generally improved participants’ spelling performance. However, the alphabetic and orthographic spelling strategies, taught during remedial interventions, would require a longer intervention phase to ensure that learning is maintained after cessation of intervention. As for the morphemic spelling strategy, taught during compensatory interventions, improvements in spelling performance indicated that this strategy is accessible to children with dyslexia.

Keywords: Dyslexia, Intervention, Spelling, Single-case design

Cite this paper: Nathalie Chapleau, Kathy Beaupré-Boivin, Interventions to Support the Development of Spelling Knowledge and Strategies for Children with Dyslexia, Education, Vol. 9 No. 1, 2019, pp. 1-8. doi: 10.5923/j.edu.20190901.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Spelling is a demanding task for all children learning to write. Some children, however, require interventions that are specifically tailored to their needs. For example, children with dyslexia, showing deficits in spelling knowledge and strategies, often fail to produce accurate spellings for words. For these children, learning to spell poses a major challenge and represents a significant barrier to the development of their ability to compose texts. Indeed, although children with dyslexia can acquire some composition skills, they struggle with those that are specifically related to written language.

2. Characteristics of the French Orthography

- The French orthography is an alphabetic system with numerous complexities ([8, 18]. It is considered an opaque orthography, as the correspondences between phonemes and graphemes are often inconsistent [37]. The phoneme /ɛ/, for example, can be spelled in many different ways (e.g., terre, élève, fête, maison, etc.). The occurrence of these graphemes is also conditioned by orthographic and morphological patterns (e.g., /ɛ/ spelled et in garçonnet). As such, to become proficient spellers in French, learners need to develop the ability to use three types of spelling strategies: the alphabetic, orthographic, and morphemic strategies.The alphabetic strategy is crucial from the beginning of spelling development. It is based on knowledge of correspondences between phonemes and graphemes, and it is used when phonemes are converted into graphemes in order to spell unfamiliar words. For example, a low-frequency word like alibi [25] can be spelled by selecting the grapheme corresponding to each phoneme in the word (a for /a/, l for /l/, i for /i/, etc.). In French, however, only half of the words can be spelled correctly using phoneme–grapheme correspondence rules [43]. As a result, spellers also need to acquire knowledge related to the orthographic strategy [37]. When using this strategy, spellers draw on their orthographic knowledge to spell familiar words (e.g., maman) as well as words in which the correspondences between phonemes and graphemes can be inconsistent (e.g., /wa/ spelled oê in poêle). Another example of the orthographic strategy is when spellers rely on orthographic patterns (e.g., /o/ spelled eau at the end of words like château) or rules (e.g., /z/ spelled s between vowels in voisin) in order to facilitate spelling. The third strategy that may be useful to spellers is the morphemic one. This strategy facilitates the spelling of polymorphemic words given the known meanings of word roots and affixes (e.g., the diminutive suffix ette in bouclette), as well as the spelling of words containing letters that mark derivational relationships between words (e.g., the silent t in chocolat, pronounced in chocolatier). In fact, most of the French vocabulary consists of morphologically complex words, as evidenced by the fact that approximately 80% of French words contain derivational affixes [9]. In sum, when learning to spell, French children need to acquire different types of knowledge that include not only phoneme–grapheme conversion rules [29], but also orthographic representations [26] and knowledge of morphological regularities [33]. For many children, this learning, which involves the acquisition of specific written language processes, is a key factor in their school careers.

3. Children with Dyslexia

- Developmental dyslexia (henceforth, “dyslexia”) is a learning disability characterized by deficits in written language processing at the word level [4]. The disorder impairs both word reading and spelling [39]. Difficulties with word recognition accuracy and fluency as well as poor decoding and spelling abilities interfere with the development of academic skills, which fall substantially below expected levels given chronological age [1]. These difficulties stem from deficits in phonological processing and orthographic coding [4, 7].Dyslexic and typically developing writers make a variety of errors when spelling words [16]. Spelling errors can be divided into three types. The first type of error involves a change in the pronunciation of the word (e.g., bateau → dateau; alphabetic strategy). Such phonological errors are frequently found in the written productions of children with dyslexia. The second type of misspelling includes phonologically plausible errors, that is, incorrect graphemes that do not change the pronunciation of the word (e.g., garçon → garsson; orthographic strategy). As for the third type, it refers to the misspelling of morphological units (e.g., fillette → fillète; morphemic strategy). These different kinds of errors are more persistent for dyslexic than typically developing writers and require interventions that are tailored to the specific learning profile of children with dyslexia [15]. In this regard, previous studies have shown that young dyslexics are sensitive to morphological information [6, 14]. The morphemic strategy enables them to access meaning despite difficulties in decoding written words. Taking morphological cues into account is a compensatory mechanism developed by children with dyslexia to facilitate access to meaning and circumvent their phonological deficits [27]. Thus, to support children with dyslexia in their learning, teachers and educators should consider the needs of these learners and focus on developing their abilities.

4. Rehabilitation

- Children with dyslexia require ongoing, specialized interventions in order to improve their spelling [44]. In the province of Québec, Canada, students who fail to meet grade-level expectations receive additional services provided by special educators called “orthopédagogues” (in French). As educational specialists with expertise in learning difficulties or disabilities, these educators (henceforth referred to as “special educators”) can support learners in their academic or professional careers [2]. For the purposes of reading and writing rehabilitation, these special educators conduct assessments and interventions based on the characteristics of learners and on those of the written language [11]. These interventions are usually delivered outside the classroom with small groups of students having similar difficulties.To facilitate learners’ appropriation of knowledge and strategies, special educators can use three types of rehabilitation approaches: the remedial, compensatory, and mixed approaches. In a remedial approach, the special educator focuses on the development of knowledge and strategies identified as deficits in learners (eg., the use of “b” instead of “d”). For children with dyslexia, a remedial approach to rehabilitation may consist of systematic instruction in phoneme–grapheme correspondences or orthographic rules [16]. In contrast, a compensatory approach focuses on the consolidation of knowledge and strategies that are accessible to learners and that can promote learning. For example, the special educator using a compensatory approach with children with dyslexia may implement interventions targeting the knowledge of morphemes (i.e., the smallest units of meaning in words) as well as spelling strategies based on derivational morphology [4]. Finally, in a mixed approach, the special educator combines remedial and compensatory activities in order to meet the learners’ needs and enable them to develop their abilities.

5. The Present Study

- Recent meta-analyses [19, 46] have confirmed that spelling instruction should be formal and explicit. Spelling interventions should also focus on spelling strategies and provide learners with many opportunities to spell new words. In the present study, considering the abilities and deficits of children with dyslexia as well as the various strategies used in spelling, remedial and compensatory interventions were delivered to students attending a special school. When applied systematically, intensively and adapted to smaller groups, the goal of both intervention was to examine the effects of these interventions on the development of spelling knowledge and strategies in 10- to 12-year-old children with dyslexia.

6. Method

6.1. Design

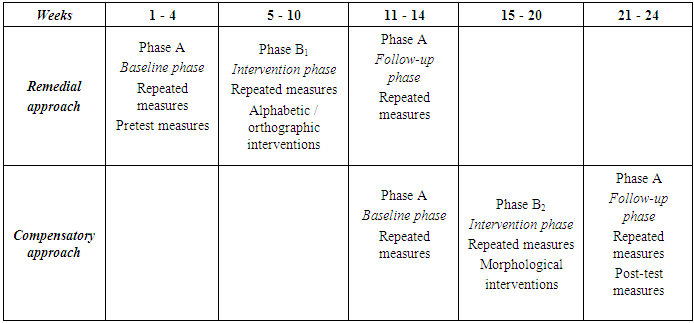

- To assess the effects of spelling interventions on children with different learning profiles, an AB1A / AB2A single-case design with repeated measures and replication across participants was used. A single-case design enables researchers to observe individual differences across participants, establish evidence-based practices and define educational interventions at the individual level [20, 22, 23, 31, 35].The study took place over 24 weeks divided into five periods (see Table 1). The first period (weeks 1 to 4) was the baseline phase for the remedial approach. A baseline was established for each participant through repeated measures of spelling. Thus, although participants received no spelling instruction, they completed the experimental dictation task for the remedial approach once a week during the four-week period. Participants also completed phonological awareness [21], morphological awareness [10], and other dictation tasks [30, 13] as pretest measures. The second period (weeks 5 to 10) was the remedial intervention phase (B1). A total of 18 rehabilitation sessions of approximately 45 minutes took place during this phase (three sessions per week). Each week focused on one specific phoneme–grapheme correspondence or orthographic rule known to be problematic for children with dyslexia. An additional weekly session was held to administer the dictation task for the remedial approach (i.e., the repeated measures). The third period (weeks 11 to 14) was the follow-up phase for the remedial approach. To assess the stability of learning after cessation of intervention, the repeated measures continued to be taken. The baseline phase for the compensatory approach also took place during the third period. This means that participants completed the dictation task corresponding to each approach over the same period. The fourth period (weeks 15 to 20) was the compensatory intervention phase (B2). This phase had the same structure as the remedial intervention phase, but the learning objectives and the dictation task were those of the compensatory approach. As such, the sessions were aimed at teaching specific knowledge about derivational morphology and a series of suffixes (ette, age, tion, ance, esse, and aire). Finally, the fifth period (weeks 21 to 24) was the follow-up phase for the compensatory approach. During this phase, the repeated measures on the words corresponding to the morphemic strategy continued to be taken each week. In addition, post-test measures were collected using the same tasks as pretest.

|

6.2. Participants

- The participants in this study had severe difficulties in learning to spell. They were aged between 10 and 12 years (mean age: 11.7 years). The identification of dyslexia was performed by a multidisciplinary team composed of a speech-language pathologist, a psychologist, and a special educator. Given their learning difficulties, participants had at least a two-year delay in their ability to recognize and produce written words. Before entering a special school, they had to repeat a grade at their local school, where they had also received special education services targeting their reading and writing difficulties. The problems persisted despite specialized interventions at school. Participants were selected after ruling out environmental factors (e.g., understimulation) as potential causes of their learning difficulties. As a result, a total of 12 participants (seven boys and five girls) were selected by the teaching staff, the educational consultant, and the researcher. This study received ethical approval from Université du Québec à Montréal. Parental consent was obtained for each participant in this study.

6.3. Procedure

- The rehabilitation interventions were based on the findings of previous research on children with learning disabilities [4, 12, 40, 41, 45]. In light of these findings, explicit and systematic instruction in spelling strategies was provided. The interventions also included a reflective component on the writing system [3] and covered the phonological, orthographic, and morphological dimensions of written language [4]. Other considerations guided the design of learning activities, such as the cumulative review of previous content and the provision of varied exercises. The instructor also gave immediate feedback to participants during the activities. The interventions were conducted with small homogeneous groups of four participants with similar difficulties.To support the development of phonological and morphological awareness as well as the participants’ ability to recognize and produce written words, 22 learning activity types were devised. The content of these activities varied depending on the rehabilitation approach used (i.e., remedial or compensatory). Each rehabilitation session consisted of three phases: the preparation, application, and integration phases [24]. The preparation phase included activities to help participants make connections between previous sessions and classroom activities, during which they had the opportunity to use their new knowledge (eg., for remedial intervention, the student had to read pseudowords with the target grapheme). This review allowed for automatization of knowledge. During the application phase, several activities allowed participants to apply the concepts being studied and produce words containing the target graphemes or morphemes (eg., for compensatory intervention, the student had to write dictated affixes or write a riddle with a polymorphemic word). To develop their orthographic representations, participants were asked to recognize and produce small linguistic units, words and pseudowords. The activities were carried out both orally and in writing. The last phase in each rehabilitation session was the integration phase. At this stage of the session, integration of new knowledge was the goal, as participants could demonstrate their ability to write the trained words by filling in the blanks in a text. This last activity was in line with the main objective underlying the rehabilitation interventions, that is, the development of knowledge about the phonological, orthographic, and morphological patterns of words in order to improve spelling accuracy.

6.4. Measures

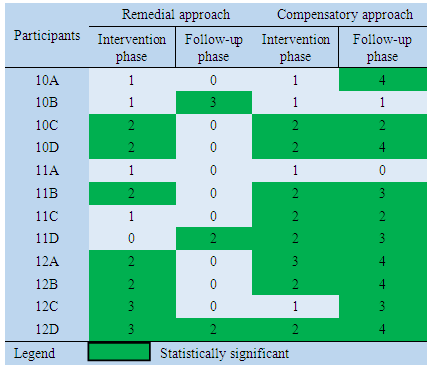

- Assessment tools are crucial in single-case designs [23]. In this study, four dictation tasks were devised to examine the effects of rehabilitation interventions. Two of these tasks allowed for the assessment of how the remedial approach affected learning. Both tasks comprised 50 words, with half of the words containing a particular phoneme–grapheme correspondence (b → /b/, d → /d/, f → /f/, t → /t/, v → /v/), and the other half, an orthographic rule (c → /s/, c→ /k/, g → /g/, g → /ȝ/, s → /z/). For each correspondence, five words were used. The first of these two tasks included the words practiced during rehabilitation sessions (e.g., nécessité, arrogant). The words in the second task had the same linguistic characteristics (word frequency, syllabic structure, number of complex graphemes, etc.) as those in the first task, but they were not presented during the sessions (e.g., pérennité, immigrant). As such, the second task allowed for the observation of participants’ ability to transfer knowledge gained from the interventions. In scoring these two tasks, one point was awarded for the correct spelling of the word (eg., calmant → calmant = 1 point; calmant → calment = 0 point), another point for a phonologically accurate spelling (eg., calmant → kalmant /kalmã/ = 1 point; calmant → galmant /galmã/ = 0 point), and a third point for accurately producing the target grapheme (eg., calmant → calmant = 1 point; calmant → kalmant /kalmã/ = 0 point; maximum 150 points). As for the other two tasks, they were devised to assess the effects of the compensatory approach. Both tasks comprised 30 polymorphemic words ending with one of the suffixes taught during the interventions (ette, age, tion, ance, esse, and aire). For each suffix, five words ware used. The first of these two tasks included the words practiced during rehabilitation sessions (e.g., clochette, tendresse), while the other task included untrained words (e.g., plaquette, faiblesse). The words in these two tasks were also equivalent on their linguistic characteristics. In scoring, one point was awarded for the correct spelling of the word, and another point for the correct spelling of the suffix (maximum 60 points). Other standardized and experimental tests were administered to participants, the results of which are not reported here (eg., phonological awareness – BALE, spelling – BELEC).The data analysis plan included methods to examine intra-individual variability. Thus, to evaluate the progress made on spelling trained and untrained words, percentage changes were calculated for each of the four dictation tasks. Percentage changes were obtained by dividing the difference between post-test and pretest scores by the maximum score possible, and then by multiplying the result by 100. The analysis of percentage change was a way to determine whether participants benefited from the interventions or simply memorized the spelling of certain words from the baseline phase through the follow-up phase. Most important, the inclusion of dictation tasks with untrained words could reveal participants’ ability to transfer the knowledge and strategies taught to them on words for which they had received no specific instruction.Given the participant-centered approach taken in this study, for each participant, two control charts were constructed based on the repeated measures of spelling taken from baseline to follow-up (one chart for the remedial approach, and the other for the compensatory approach). Each control chart included data points for the repeated measures as well as an interval called “band of confidence.” The line at the center of the band of confidence was at the level of the mean of baseline scores. To determine the upper and lower limits of the band of confidence, the standard deviation of both baseline and intervention scores was calculated for each participant. The limits were two standard deviations above and below the central line. A common practice is to consider that interventions have significant effects when two successive data points fall outside the band of confidence or when one data point is three standard deviations above or below the central line (Juhel, 2008; Satake, Jagaroo, & Maxwell, 2008).

7. Results

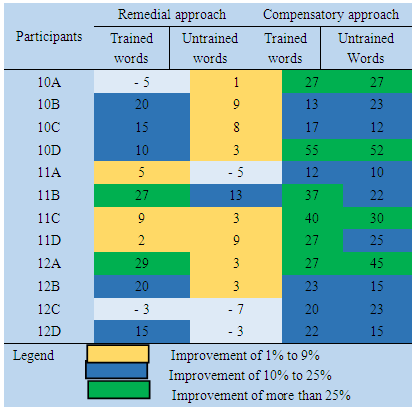

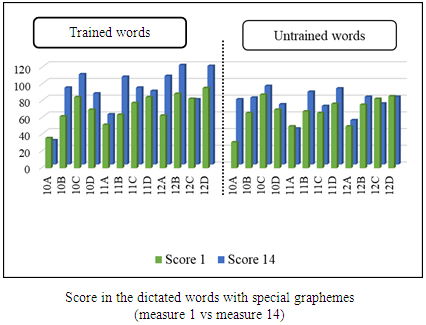

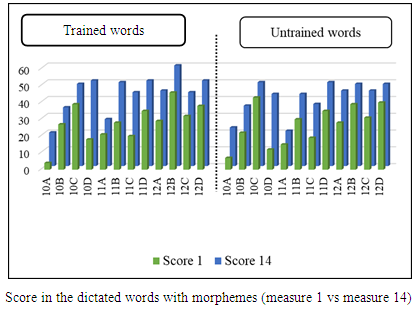

- One of the specific goals of this study was to determine the extent to which rehabilitation interventions based on a remedial approach and those based on a compensatory approach affected the spelling performance of children with dyslexia. For the presentation of the results obtained by each participant, in this article, only the score of measure 1 and 14 are shown (Figure 1 and Figure 2).

| Figure 1. Remedial intervention |

| Figure 2. Compensatory intervention |

|

|

8. Discussion

- Rehabilitation interventions aimed at the development of spelling skills, whether the approach is remedial or compensatory, usually improve the spelling performance of children with dyslexia. As in previous studies of students with learning disabilities [19, 28, 42], explicit instruction and content-specific activities facilitated the acquisition of the knowledge and strategies being taught. As such, to help children with dyslexia acquire the knowledge necessary to spell words accurately, educators need to design systematic interventions focusing on the alphabetic, orthographic, and morphemic strategies. Repetition and cumulative review of previous content promote the development of automaticity in processing words and parts of words.Although they made progress, some participants in this study did not improve significantly or did not maintain their learning after cessation of intervention. As shown in a systematic review by Williams et al., (2016) [46], more hours of intervention might be necessary to obtain stronger effects when the development of spelling skills is the goal. This might particularly apply to learning through a remedial approach. As suggested by the analysis of percentage change in the present study, more explicit and intensive instruction might be necessary to meet the needs of children with dyslexia and enable them to develop spelling strategies despite their phonological and orthographic deficits.Turning to the compensatory approach, as shown in previous studies [5, 34], morphological instruction can be beneficial to children with dyslexia given that it allows them to acquire knowledge and strategies that are accessible to them. In turn, this learning helps them to spell polymorphemic words, which are abundant in the French language [9]. Compensatory interventions might also enable children with dyslexia to focus more on their deficits. Indeed, given that the morphemic strategy facilitates the spelling of morphemes in polymorphemic words, it might also facilitate the use of alphabetic and orthographic strategies to spell other parts of these words. The morphemic strategy, however, cannot be used to spell all words correctly. It follows that a mixed approach to rehabilitation, combining elements from the remedial and compensatory approaches, could be an interesting avenue for interventions aimed at developing dyslexic students’ spelling skills. Like typically developing writers, these learners need to be able to use spelling strategies simultaneously and automatically in order to become proficient spellers.An interesting finding of this study was the improvements in the dictation tasks for untrained words. This was especially true for the compensatory approach, which further suggests that the morphemic strategy is accessible to children with dyslexia. This finding also suggests that children with dyslexia may be able to transfer their learning when spelling words that are linguistically similar to those in their orthographic lexicon.The results of this study suggest that instruction in spelling knowledge and strategies can reduce the cognitive load associated with spelling. Therefore, such knowledge and strategies might help children with dyslexia develop their ability to compose texts at a level equivalent to their other composition skills [17, 32]. Future studies should examine how children with dyslexia integrate spelling knowledge and strategies in their written compositions.A limitation of the present study was the number of participants, which was relatively small given the selection criteria and the study design used. Although this prevents the generalization of findings to the whole dyslexic population, adherence to methodological standards for single-case designs [23] ensures that the results are statistically valid. Therefore, as regards spelling interventions, the conclusions drawn from the interpretation of the results should provide clear indications to educators working with children with dyslexia: Effective spelling instruction should be explicit, systematic, and focused on spelling strategies.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- This study would not have been possible without the collaboration of students, teachers, and research assistants. It was funded by the Fonds de recherche du Québec – Société et culture (FRQSC). Special thanks go to Maxime Gingras, for the translation of this article.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML