| [1] | Abe, K., Ozawa, K., Suzuki, Y., & Sone, T. (2006). Comparison of the effects of verbal versus visual information about sound sources on the perception of environmental sounds. ACTA Acustica United with Acustica, 92, 51–60. |

| [2] | Agency for Cultural Affairs, Government of Japan. (1970). Chosakukenhou dai 35 jou (Copyright Law, Article 35). Retrieved from http://law.e-gov.go.jp/htmldata/S45/S45HO048.html. |

| [3] | Azuma, J. (2008). Applying TTS technology to foreign language teaching. In F. Zhang & B. Barber (Eds.), Handbook of research on computer-enhanced language acquisition and learning (pp. 497–506). New York: Information Science Reference. |

| [4] | Chosakukenhou dai 35 jou gaidorain kyougikai. (2004). Gakkou sonotano kyouikukikannniokeru chosakubutsuno hukuseini kansuru cyosakukenhou dai 35 jou gaidorain (Copyright Law Article 35 guidelines for duplication of work in schools and other educational institutions). Retrieved from http://www.jbpa.or.jp/pdf/guideline/act_article35_guideline.pdf. |

| [5] | Copyright Law Department, Agency for Cultural Affairs, Government of Japan. (2015). Gakkouni okeru kyouikukatudouto chosakuken (Educational activities in schools and copyright). Retrieved from http://www.bunka.go.jp/seisaku/chosakuken/seidokaisetsu/pdf/gakko_chosakuken.pdf. |

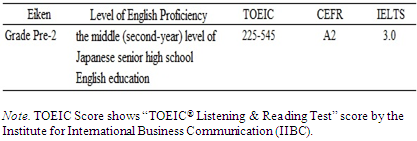

| [6] | Eiken Foundation of Japan. (2016a). Kaku kyuu no meyasu (Standard of each grade). Retrieved from http://www.eiken.or.jp/eiken/exam/about/. |

| [7] | Eiken Foundation of Japan. (2016b). 2016 nendo karano atarasii gouhi hantei houhou ni tuite (A new gideline for admission criteria starting from fiscal year of 2016). Retrieved from https://www.eiken.or.jp/eiken/exam/2016admission.html. |

| [8] | Eiken Foundation of Japan. (2017). About EIKEN Grade Pre-2. Retrieved from http://www.eiken.or.jp/eiken/en/grades/grade_p2/. |

| [9] | Halliday, M. A. K., & Greaves, W. S. (2008). Intonation in the grammar of English. London: Equinox. |

| [10] | Hanamoto, H. (2010). How do the stereotypes about varieties of English relate to language attitude?: a quantitative and qualitative study of Japanese university students. The Japanese Journal of Language in Society, 12 (2), pp. 18–38. |

| [11] | Harashima, H. (2006a). Review of “VoiceText.” Electronic Journal of Foreign Language Teaching, 3 (1), 131–135. Retrieved from http://e-flt.nus.edu.sg/v3n12006/rev_harashima.pdf. |

| [12] | Harashima, H. (2006b). Onsei gousei ni yoru eigo risuningu sozai no sakusei (Creating English listening materials using speech synthesis). Proceedings of the 22nd Annual Conference of Japan Society for Educational Technology, 789–790. |

| [13] | Hatori, H. (1977). Eigokyouiku no shinrigaku (Psychology of teaching English). Tokyo: Taishuukanshoten. |

| [14] | Ishikawa, K. (2005). Kotobato shinri (Language and psychology). Tokyo: Kuroshiosyuppan. |

| [15] | Jones, C., Berry, L., & Stevens, C. (2007). Synthesized speech intelligibility and persuasion: Speech rate and non-native listeners. Computer Speech and Language, 21, 641–651. |

| [16] | Kadota, S. (2006). Dai ni gengo rikai no ninchi mecanizumu (Reading and phonological processes in English as a second language). Tokyo: Kuroshio Syuppan. |

| [17] | Kadota, S. (2012). Syadouingu ondokuto eigosyuutokuno kagaku (Science for shadowing RA and English acquisition). Tokyo: Cosmopier. |

| [18] | Kadota, S. (2015). Syadouingu ondokuto to eigo komyunikeisyon no (Science for shadowing RA and English communication). Tokyo: Cosmopier. |

| [19] | Kataoka, H. (2007). The study of memory: Retention of English and Japanese proverbs (Unpublished master’s thesis). Graduate School of Foreign Language Education and Research, Kansai University: Osaka. |

| [20] | Kataoka, H. (2009). Text-To-Speech (TTS) synthesis technology wo katsuyoushita eigo kyouikukyouzai no kaihatsu to nihonjin no onseininshiki (The use of Text-To-Speech (TTS) synthesis technology for English education: Speech recognition of Japanese EFL learners). Journal of Kansai University Graduate School of Foreign Language Education and Research, 7, 1–33. |

| [21] | Kataoka, H., & Ito, M. (2013). A comparative study on reading aloud: Instruction by Text-To-Speech synthesis sounds and a high school Japanese English teacher. THE JASEC BULLETIN, 22 (1), 39–54. |

| [22] | Kataoka, H., Ito, M. & Yamane, S. (2015). Retention of English sentences learned by reading aloud using Text-To-Speech (TTS) speech sounds: A longitudinal study in a Japanese high school. International Journal of Research Studies in Educational Technology, 5 (1), 29–47. DOI: 10.5861/ijrset.2015.1331. |

| [23] | Kataoka, H. (2018). Producing English speech sounds by Text-To=Speech tecnology for English as a foreign language education in Japan. International Journal of Education and Socia Science Redearch, 1 (2), pp. 34–48. |

| [24] | Kent, R. D., & Read, C. (2002). The Acoustic analysis of speech (2nd ed.). New York: Singular Pub Group. (T. Arai, T. Sugawara, Trans.). (1996). The Acoustic analysis of speech (Onsei no Onkyoubunseki). Tokyo: Kaibundo Publishing Co., Ltd. |

| [25] | Kido, H., & Kasuya, H. (1999). Tsuujou hatsuwa no seishitsu ni kanren shita nichijou hyougengo no chuushutsu (Extraction of everyday expression associated with voice quality of normal utterance). The Journal of the Acoustical Society of Japan, 55 (6), 405–411. |

| [26] | Kohno, M. (1984). Eigojugyou no kaizou (Remodeling of English language lessons). Tokyo: Tokyoshoseki. |

| [27] | Komatsu, M. (2011). Acoustic phonetics (Onkyou onseigaku). In H. Joo, T. Fukumori, & Y. Saito (Eds.), Dictionary of basic phonetic terms (Onseigaku kihon jiten) (pp. 115–122). Tokyo: Bensei Publishing Inc. |

| [28] | Ladefoged, P. (2003). Phonetic data analysis: An introduction to fieldwork and instrumental techniques. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing. |

| [29] | Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT). (2015c). Kakusikendantaino deetaa niyoru CEFRtono taisyouhyou (A comparison table of scores among CEFR and other certification association). Retrieved from https://0x9.me/CQsZ6. |

| [30] | Miyasako, N. (2006) Bumonkousei ondoku shoriteki kenchikarano ondokuno shorontenni kansuru seiri (A critical review of oral reading issues from the componetal processing view of oral reading). Language Education & Technology, 43, 139–159. |

| [31] | Miyasako, N. (2007). A theoretical and empirical approach to oral reading. Language Education & Technology, 44, 135–154. |

| [32] | Mizumoto, A. (2012). Sokutei no datousei to sinraisei (Validity and reliability of measurement). In O. Takeuchi & A. Mizumoto (Eds.), Gaikokugo kyouikukenkyuu handobukku (The Handbook of Research in Foreign Language Learning and Teaching) (pp. 17–30). Tokyo: Shohakusya. |

| [33] | Mizumoto, A., & Takeuchi, O. (2008). Kenkyuuronbun ni okeru koukaryou no houkoku no tamei: Kisoteki gainen to cyuuiten (Basics and considerations for reporting effect sizes in research papers). Studies in English Language Teaching, 31, 57–66. |

| [34] | NextUp.com. (2018). Get the best voices available for TextAloud 4 on your PC! Retrieved from https://nextup.com/index.html. |

| [35] | Palmer, H. E. (1921). The principles of language study. In the Institute for Research in Language Teaching (Ed.), The selected writings of Harold E. Palmer: Pāmā senshū, Dai 1 Kan, (1999), (pp. 331–520). Tokyo: Hon-no Tomosha. |

| [36] | Robinson, D.W., & Dadson, R.S. (1956). A re-determination of the equal-loudness relations for pure tones. British Journal of Applied Physics, 7, 166–181. |

| [37] | Ryalls, J. (1996). A basic introduction to speech perception. San Diego, CA: Singular Publishing Group. (S. Imatomi, T Arai, T. Sugawara, K. Shintani, Y. Kitagawa, & K. Ishihara, Trans.). (2003). Onsei chikaku no kiso (A basic introduction to speech perception). Tokyo: Kaibundo Publishing Co., Ltd. |

| [38] | Sonobe, H., Ueda, M., & Yamane, S. (2009). The effects of pronunciation practice with animated materials focusing on English prosody. Language Education & Technology, 46, 41–60. |

| [39] | Stevens, S. S., Volkman, J., & Newman, E. B. (1937). A scale for the measurement of the psychological magnitude pitch. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 8 (3), 185–190. |

| [40] | Sugito, M. (1996). Nihonjinno eigo (Japanese English). Osaka: Izumishoin. |

| [41] | Suzuki, Y., & Takeshima, H. (2004). Equal-loudness-level contours for pure tones. Journal of Acoustical Society of America, 116 (2), 918–933. |

| [42] | Takeuchi, O. (2012). t kentei nyuumon (Beginning guide to t-test). In O. Takeuchi, & A. Mizumoto (Eds.). Gaikokugo kyouikukenkyuu handobukku (The handbook of research in foreign language learning and teaching). (pp.62–70). Tokyo: Shohakusha. |

| [43] | Takeuchi, O., & Mizumoto, A. (Eds.) (2012). Gaikokugo kyouikukenkyuu handobukku (The handbook of research in foreign language learning and teaching). Tokyo: Shohakusha. |

| [44] | The Japan Times ST. (2007). Eigo to beigo no hatsuon (Brirish and American pronunciation). Retrieved from https://0x9.me/Cjqa8. |

| [45] | Uchida, T. (2009). Onsei no inritsuteki tokuchou to washa no personality inshou no kankeisei (Proposing the prospect model: Relationship between the prosodic features of speech sound and the personality impressions). Journal of the Phonetic Society of Japan, 13 (1), 17–28. |

| [46] | Yamanishi, H. (2012). Bunsanbunsekinyuumon (Beginning guide to analysis of variance; ANOVA). In O. Takeuchi, & A. Mizumoto (Eds.). Gaikokugo kyouikukenkyuu handobukku (The handbook of research in foreign language learning and teaching). (pp.71–82). Tokyo: Shohakusha. |

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML