-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Education

p-ISSN: 2162-9463 e-ISSN: 2162-8467

2017; 7(5): 100-106

doi:10.5923/j.edu.20170705.03

Adequacy of Government Funding on the Implementation of Subsidized Public Secondary Education Public Secondary Schools in Bureti Sub-County, Kericho County

Joice Chelangat Chirchir1, Hellen Sang2, Erick Mibei3

1Education Administration, University of Kabianga, Kericho, Kenya

2Department of Curriculum Instruction and Education Media (CIEM), University of Kabianga, Kericho, Kenya

3University of Kabianga, Kericho, Kenya

Correspondence to: Joice Chelangat Chirchir, Education Administration, University of Kabianga, Kericho, Kenya.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2017 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

In the last decade, the government of Kenya has emphasized the provision of education as a leading policy imperative. The provision of subsidized secondary education (SSE) is very important in Kenya given that the country is a low income one. The purpose of this study was to establish the adequacy of government funding on the implementation of the SSE in Bureti Sub-County, Kericho County. The study adopted descriptive study survey research design from quantitative research paradigm as the main design complemented by naturalistic research design from qualitative research paradigm, to study the factors influencing the implementation of SSE. The study targeted all Principals/Deputy Principals, all teachers; one Sub-county Director of Education, and one District Quality Assurance and Standard Officer in Bureti Sub-county. The population of the study was 50 schools in the sub-county where 149s participants took part. A sample of 15 schools, 15 principals, and 132 teachers 1 Sub-county Director of Education, 1 District Quality and Standards Officer was included in the study. Simple random, systematic and stratified sampling procedures were used. Data was collected using questionnaires for the principal and teachers, interview schedules were used to get information from the SCDE and DQASO. Data analysis was done using descriptive statistics after data cleaning and coding. Quantitative data was analyzed using frequency counts, means and percentages while qualitative data was analyzed by using tallying the numbers of similar responses. Results of data analysis were presented using frequency distribution tables, bar graphs and pie charts. The statistical package of social science (SPSS) program formed part of the analysis. The findings showed that the major factors facings implementation of SSE included; Delay in disbursing the SSE funds, over enrolment of students leading to strained physical facilities, inadequate facilities, lack of funds from the government for expansion, acute teacher shortage and poor cost sharing strategies. The following recommendation have been made, budgetary allocation review, disbursement of funds should be timely, employ more teachers, identify and assist those students who are eligible to enroll to secondary schools and provide the infrastructure. Further research can be conducted to identify cost cutting measures in secondary schools.

Keywords: Adequacy, Government funding, Subsidized Secondary Education

Cite this paper: Joice Chelangat Chirchir, Hellen Sang, Erick Mibei, Adequacy of Government Funding on the Implementation of Subsidized Public Secondary Education Public Secondary Schools in Bureti Sub-County, Kericho County, Education, Vol. 7 No. 5, 2017, pp. 100-106. doi: 10.5923/j.edu.20170705.03.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Education is widely seen as one of the most promising paths for individuals to realize better, more productive lives and as one of the primary drivers of national economic development [21]. Education also forms the basic component upon which economic, social and political development of any nation is founded [25]. Investment in education can help foster economic growth, enhance productivity, contribute to national and social development and reduce social inequality. According to UNESCO [21] the level of a country’s education is one of the key indicators of its level of development. Globally, education is recognized as a basic human right. Education for all has been discussed in international forums, for example United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) World Conference at Jomtien, Thailand in 1990 and its follow up in Dakar, Senegal in 2000. Consequently, governments around the world have invested huge amounts of their expenditure on education. Before independence, education for most African countries was geared towards perpetuating and producing aims and content inherited form the pre-independent past. The current re-thinking however ensures that the African is rooted in the culture of his/her environment and prepared for participation in nation building through educational reforms [28]. The Organization of African Unity has also stated the importance of government in ensuring that children’s rights are achieved by providing free and compulsory basic education [19]. The citizens and the government of Kenya have invested heavily in improving both the access and quality of education in an effort to realize the promise of education as well as to achieve the education related Millennium Development Goals and Vision 2030. In response to Education for All as agreed in different forums, Universal Primary Education has been implemented in the East African Countries and it has resulted in high enrolment rates of pupils in primary school level as evidenced by 215% increases in primary school enrolment in Kenya (MOE, 2008). Despite the tremendous increase in primary school access, secondary school access has remained low. In 2009, the secondary school net enrollment rate was approximately 50% (World Bank, 2009), while in 2010 the primary to secondary school transition rate was equally low at 55% [7, 9].The growth in secondary schools shows a demand for this level of education by the increased number of primary school leavers over the years and more recently as the introduction of free primary education in 2003 [5]. This has resulted in enrolling students beyond the approved 40 students per class (Republic of Kenya, 1998). Over enrolment stretches the resources, both physical and human, hence impact on the quality of teaching.Accessibility to quality, relevant and affordable secondary education has remained elusive to many Kenyans. The major hindrances included high cost of access, high levels of poverty, extra levies for private tuition and environment especially for children from poor household and those with special needs. Negative effects of HIV/AIDs pandemic raising repetition rate, low expansion of public secondary schools, and the requirements that households pay user changes while the D.E.B are some of the challenges that the programme has been facing. Statement of the ProblemSubsidized Secondary (SSE) policy was launched in 2008 with an aim of ensuring that all primary school pupils from class eight are able to continue with secondary education. Implementation of Subsidized Secondary Education in Kenya was a major step in expanding access to education to majority of students from poor background. This was further reinforced by the international agreement on Education for All [28]. The government provided subsidies towards funding SSE, however there were other costs that were not catered for by SSE but were to be catered for by the parents. Concerns have however been raised over effective implementation of this programme, and the impact of SSE on quality and access of secondary education following structural factors including inadequate and delayed disbursement of subsidies to school, shortage of human resources, limited physical and instructional resources [12]. Significance of the StudyThe findings of this study will be beneficial to the government, policy makers, educational officials, teachers, school administrator and the donor community. This is so because the study assesses the gaps and weaknesses of the SSE policy so far and how the government can assist in enhancing access, equity, retention and completion rates.Education officials will benefit from the study in that they will be able to ensure that the SSE policy is able to assist bright needy students to be retained in school and not forced out due to lack of financial assistance. They will also be able to ensure equity and access to education of children irrespective of their humble background, race or religion differences.

2. Literature Review

- The first country in sub-Saharan Africa to start Universal Secondary Education (U.S.E) was Uganda, in February 2007. The USE or SSE was aimed at doubling the number of those joining secondary schools continuing with learning. According to the Acting Ugandan Education Commissioner in the year 2007, the programme was envisaged to help rural communities to produce people who actively participate in economic activities. The programme was an immediate success story as enrolment in secondary schools skyrocketed from 150,000 to 380,000 taking up 90% of all primary school graduants, that is, 90% transition. Under the UPE and Universal Secondary Education (USE) initiatives, the government provides funds for provision of basic school requirements for primary and secondary school learners. These include textbooks and other instructional resources.Through the MOES, the government has also undertaken the training and employment of qualified teachers and the provision of a conducive environment for school going children by constructing classrooms to accommodate the increasing number of learners. The maintenance of feeding programmes for schools and the provision of safe drinking water through sinking boreholes and digging protected water wells are all part of the government’s commitment to ensure the success of UPE and USE [18].Some of the limitations of the programme were that head teachers input were not sought in planning and they were not trained sufficiently in knowledge and skills on implementation (Oyaro, 2008). It is clear that in developing nations such as Uganda and Kenya, free schooling is a big relief to many people and therefore such a programme registers immediate success. However, poor planning and limited enhancement of the principal’s capacity to manage the programmes negatively influences the achievements of the desired goals. This incapacity limited the possible level of success of the programme.Zambia established in 1996 Education Production Units which enroll students who failed to find regular places in fee-paying afternoon sessions run by teachers (who participate on a voluntary basis to supplement their income) in school premises. In Rwanda 80% of the students are enrolled in private schools, almost 40% of which receive no public subsidy and have to rely on fee income [24].In Benin the majority of the teachers in junior secondary schools are local contract teachers paid at least in part by the parents. In the Democratic Republic of Congo, parents pay more than 80% of the cost in both private and public secondary schools [26]. In Burkina Faso the government provides two government paid teachers for every newly established lower secondary school; communities and other providers are expected to contract additional teachers needed [27].Other challenges facing secondary education in SSA countries concern provision of goods and services for schools. Most SSA countries no longer rely on public entities for the provision of goods and services, in particular classrooms and textbooks. Textbooks are procured from private contractors sometimes hired by schools or communities build most schools [15].Free education has its origin in industrialized world. According to [17] some education has been available since ancient times. In England, a fairly good number of schools trace their origins back to the days of Queen Elizabeth. In the United Kingdom elementary education did not become compulsory until 1870 while very limited free secondary education was introduced in 1907 and it was not until 1944 that universal FSE was introduced.According to [1] education has a long history of significance in Kenya. Before the nation achieved independence, access to education was extremely limited under colonial rule. While primary education was a requirement for British Children, very few Kenyans had the opportunity to go to school to school even if they desired it. In Kenya the clamour for free secondary school education started after 1963, after the country became independent. This was due to increased demand for labour for middle and upper level government personnel [22]. Kenyatta promised free education to disadvantaged peoples living in Arid and semi-arid lands of Kenya in 1971.The Kenyan government realizes that education and training will contribute to national development. However, the cost of provision of education has risen as a result of rising enrolment due to increased social demand and high expenditure on teachers’ salaries [2].School management plays a major role in the management of all school financial activities which involve disbursement of money. Orlosky [13] noted that financial management determines the way the school is managed and whether or not it meets its objectives. Chiuri and Kiumi [2] argued that developing countries have experienced high increase in their expenditure on education than in the growth of their national economies. They pointed out that in 1983, for example, Kenya and Nigeria respectively allocated 15.3% and 16.3% of their total expenditure on education.Introduction of subsidized secondary education shows the government’s commitment to provision of secondary education to all Kenyans. However without development of human resources and posting of adequate teachers to schools, the quality of education could be compromised. Onyango [12] emphasizes that human resource is the most important resource in the school organization. He adds that teachers comprise the most important resource in the school. The contribution of other staff members such as the bursars, accountants, clerks, matron, nurses, messengers and watchmen is also important. He further noted that the most important purpose of a school is to provide children with equal and enhanced opportunities for learning and the most important resource a school has for achieving that purpose is the knowledge, skills and education of its teachers. Teachers therefore need to be well managed through proper motivation and leadership. With an increase in enrolment due to SSE, teacher, pupil ratio is likely to be high, leading to an increased workload for the teachers. This is likely to pose a challenge to schools which are expected to ensure that the quality of education being offered is not compromised.The poor economic performance and rising poverty level in the two countries have raised questions on the justification of heavy public expenditure in the sector [9]. Kenyan parents and citizens have reacted by blaming the government expenditure for lack of control education system which has become very expensive with schools charging fees as they pleased. Reforms were then mooted, which included limiting government expenditure on education, cost sharing and encouraging private individuals and non-governmental organizations to invest in the sector, cost sharing policy was then introduced in Kenya in 1988, with the aim of having families contribute to the financing of education. Although cost sharing appeared to be the solution to the problem of financing education in Kenya, it however created a lot of problems in the sector where poor households could not raise the required fees such as those for security, activity and building. The Government subsidy to public secondary schools under the FDSE program is based on an annual capitation grant for each student that is disbursed to schools annually in three tranches. The boarding fee component is met by the parents Republic of Kenya [23].

3. Methodology

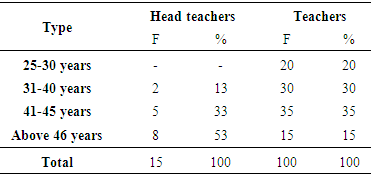

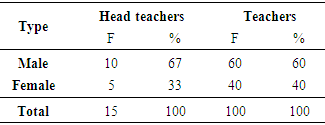

- Research DesignThe study employed descriptive survey research design. Descriptive survey research designs were used in preliminary and exploratory studies to allow researchers to gather information, summarize, present and interpret for purposes of clarification [14]. The study fitted within the provisions of descriptive survey research design because the proposed study collected data and report the way things were without manipulating any variables.Target PopulationThe target population for this study consisted a sample of secondary schools in Bureti Sub-county, Kericho County which has fifty (50) public secondary schools. The subject for study included a sample of 15 secondary school principals and 100 teachers from the schools. Others subject of study will include 1 SCDE and 1 DQASO of Bureti Sub-county.Sample and Sampling ProceduresThe purpose of stratification was to organize the sampling frame into homogenous subjects from which the sample was drawn and to provide each school with an equal chance of being included in the study. Simple random sampling technique was used to select 15 schools, 15 principals in public secondary schools and 132 teachers. To ensure fair representation of the study population, proportionate stratified sampling was used in selecting and distributing the 15 schools. This was to ensure that sample was adequately distributed among the three educational zones. This guaranteed that all the zones were involved in the study.Data collection InstrumentsQuestionnaires, interview schedule and observation checklist were used to collected data. The questionnaires was distributed to the respondent and then collected after being filled. On the other hand, the interview schedule was used to carry out face to face interview with the key interview guide. The questionnaires and the interview schedule provided more insight and information as regard to factors influencing the implementation of Subsidized Secondary Education. Observation checklist according to Kasomo [7] is a checklist with a list of behaviors exhibited by particular aspects used by the research. It contained items that guided researcher to obtain information on the programme as it occurs. The researcher used it in schools under study to determine two aspects expected to be physically available; the nature and status of infrastructural facilities like, classrooms, desks, computer laboratories and libraries. Validity of data collection instrumentsValidity is defined as the accuracy and meaningfulness of inferences, which are based on the research [10]. It is the degree to which results obtained from the analysis of the data actually represent the phenomena under study. The research instruments were validated in two ways. First the researcher formulated items in the instruments by considering the set objectives in order to ensure that they contained all the information that answered the research questions. Second, the researcher consulted the supervisor and other experts from the school of Education, University of Kabianga for their opinion on the instruments.Data Analysis and PresentationThis involved editing, coding, classification and tabulation of collected data. Editing involved a careful scrutiny of the completed questionnaires/interview schedules to detect errors, omissions and blanks. Those that were not complete were discarded at this stage. This helped to ensure that the data are accurate, consistent with appropriate facts collected. Coding involved assigning numerals to answers so that responses are summarized. Classification involved arranging the data in groups or classes on the basis of characteristics. Using the Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS) software, data files were created for processing. This yielded both qualitative and quantitative data. Qualitative data was analyzed qualitatively using content analysis based on analysis of meanings and implications emanating from respondents information and documented data. As observed by Gray [4] qualitative data provides rich descriptions and explanations that demonstrate the chronological flow of events as well as often leading to chance findings. On the other hand, quantitative data was analyzed using descriptive statistics such as frequency counts percentages, mean and standard deviation. The data was presented using pie chart, bar graphs, percentages and frequency tables.Ethical ConsiderationBefore the commencement of the study, permission was sought from the Board of postgraduate studies, NACOSTI, the respective SCDE and individual principals in the target schools. Participation in the research was voluntary and no coercion in whatever way. Direct consent was sought from head teachers and other respondents and confidentiality was observed throughout the study.

4. Results

|

|

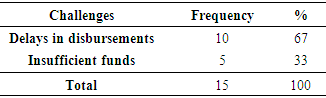

|

5. Discussion

- The study found out that the least support the schools got was in the form of disbursement of funds. Most of the respondents were unanimous that the disbursement of the funds to schools was not prompt and that disbursement was done in piecemeal basis. This delayed disbursement of funds affected budgeting and planning. This also affected the timely acquisition of teaching learning resources.The study further established that the funds provided for the programme was not adequate. All the respondents concurred that the funds provided by the government was inadequate. The most affected vote heads included, Activity, Medical, Personal Emoluments.The results also found that majority of the schools in Bureti sub-county state that funds for free secondary education are not adequate. From the study, majority of the headteachers 10 (67%) indicated that there were delays in disbursements of funds for the implementation of SSE.

6. Conclusions

- The government funding was not adequate and there were delays in disbursement of the funds which affected the effective implementation of the FSE and purchasing power of the schools.Free secondary education increased enrolment which has caused overstretching of the available resources. The government has not budgeted for the extra students who enroll which also affected the proper implementation of the program.

7. Recommendations

- The disbursements of funds by the government to secondary schools to be timely and adequate and should be in harmony with the calendar of schools activities, in order to avoid schools experiencing lack of purchasing power within certain periods the year.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML