-

Paper Information

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Education

p-ISSN: 2162-9463 e-ISSN: 2162-8467

2017; 7(5): 96-99

doi:10.5923/j.edu.20170705.02

Pupils’ Personal Factors that Lead to Girls Drop-Out from Primary Schools in the Tea Estate Schools in Kericho County

Moses Koech1, Syallow C. Makero2, Andrew Kosgei3

1Med Student, (Education Administration), University of Kabianga, Kenya

2Department of Nursing, University of Kabianga, Kenya

3Department of Curriculum Instructions and Education Management, University of Kabianga, Kenya

Correspondence to: Moses Koech, Med Student, (Education Administration), University of Kabianga, Kenya.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2017 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

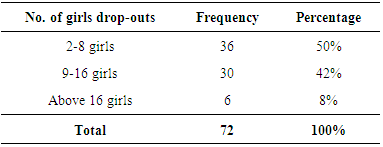

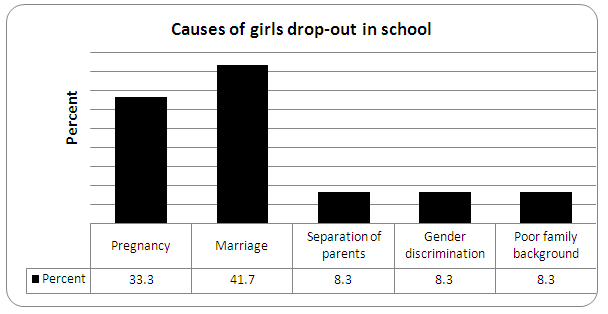

Drop-out among girls is a serious issue resulting from various causes. There is overwhelming statistics that a high number of girls are dropping out of school compared to boys. Most of these girls drop-out in January after the long festive season. The purpose of this study was to investigate pupils personal factors that lead to girls Drop-out from primary schools in the Tea estate in Kericho County. The study employed descriptive survey design. The theoretical framework used was Liberal Feminism which bases its theories on natural justices, human rights and democracy. The research findings of this study will provide useful information to the youths, stakeholders and education planners in designing customized strategies and interventions to the problem. The total target population consisted 2020, of which 200 were teachers, 1800 were pupils and 20 Head Teachers. The researcher sampled 72 respondents to take part in the study; this sample was convenient for the researcher. The respondents include headteachers, class teachers and pupils. Our target schools were 6. The main instruments for data collection were questionnaires and school records. Data collected was analyzed qualitatively and quantitatively through descriptive statistics. Frequency tables and bar-graphs were used in this analysis. Validity of instruments was improved through expert judgment. The necessary adjustments were made to enhance their validity. Reliability was measured by test-retest technique. The study found-out that the major causes of girls’ dropout were early marriages as it was agreed by 41.8% of the respondents and others include early pregnancy (33.3%), and gender discrimination (8.3%). The researcher recommended that management of schools and those of Estate Companies should provide girls with the necessities such as sanitary towels to avoid absenteeism during menses.

Keywords: Drop out, School based factors, Social cultural factors, Personal factors

Cite this paper: Moses Koech, Syallow C. Makero, Andrew Kosgei, Pupils’ Personal Factors that Lead to Girls Drop-Out from Primary Schools in the Tea Estate Schools in Kericho County, Education, Vol. 7 No. 5, 2017, pp. 96-99. doi: 10.5923/j.edu.20170705.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- The issue of school dropout has wasted a lot of resources since girls start school and fail to graduate either to the next class or to secondary school. Kenya has invested a lot in education and when girls do not complete education it becomes a complete loss. Schools in the Tea Estate of Kericho County are not spared either by dropout. Many girls have dropped out of school and rendered education valueless.UNICEF [14] report indicates that girls’ education leads to more equitable development, stronger families, better services, better child health and effective participation in governance. Despite the obvious benefits of education to national development, research findings indicate that girls dropout rate from school is higher than that of boys. Osakwe, [16] observed that Nigerian girls, for various reasons bordering on religious, cultural, socio-economic and school related factors, are not given a fair chance in the educational sector. In Nigeria, about 7.3 million children do not go to school, of which 62% are girls [20]. The same UNICEF report indicates that girl’s primary school completion rate is far behind that of boys, at 76% compared with 85% for boys. This gender gap means that millions more girls than boys are dropping out of school each year. This goes to show that the majority of children not in school are girls, UNICEF [20] noted a worrisome report from sub-Saharan Africa where the number of girls out of school rose from 20 million in 1990 to 24 million in 2002. The report also indicated that 83% of all girls out of school in the world live in Sub – Saharan Africa, South Asia, East Asia and the Pacific.Mohammad [11] equally reported that a girl may be withdrawn from school if a good marriage prospect arises. Early marriage is a socio-cultural factor that hinders the girl child’s access to school. Some parents, in an attempt to protect their teenage daughters, give them out to wealthy old friends. Some of these girls who attempt to escape from such forced marriages end up in disaster. Efforts should be made to ensure that girls go to school and complete their schooling. According to Egbochuku [5] efforts made to ensure that adolescent girls who re-enrolled in school are retained with a view to acquiring education will permanently close the door to poverty and ignorance and at the same time open that of prosperity in terms of economic buoyancy, social advancement and civilization.According to Begum [2] about 72,000 female teenagers missed school in 2005 due to early pregnancies in South Africa. The highest rate of teenage pregnancy in the world is in Sub-Saharan Africa [19]. Studies done in Niger for example, revealed that 87% of women surveyed were married and 53% of these women had given birth to a child before the age of 18. Kenya is not an exception with this wastage of education due to the mentioned problems above. Kericho schools especially those in the Tea Estates are also faced with great wastage of education due to early pregnancies and early marriages. Statement of the ProblemEducation which is the right of every child is a mirage in the lives of some Kenyan girls because some of them are forced into early marriage as from 12 years Murugi, (2008). Murugi further observed that the regression in basic education is reflected in the fact that the net enrolment rate for girls is very low, with a high dropout rate. Poverty has been known to force most parents to withdraw their children from school UNICEF, (2004). This UNICEF report also indicates that some 121 million children in the world are out of school for various reasons and that 65 million of them are girls. With the educational rights of 65 million girls unmet, something should be done to ensure that they complete their education [18]. The UNICEF, 2004 report indicates that Kenya is one of the 25 developing countries of the world with low enrolment rates for girls. The gender gap of more than 10% in primary education and with more than half a million girls out of school is a problem that requires emergency action if the nation is to advance technologically, considering the multiplier and intergenerational benefits derivable in the education of the girl child [9]. It is the aim of this study, therefore, to find out reasons why girls dropout of school in Tea Estate Schools, Kericho County, and consequently, based on findings suggest counseling strategies that could be adopted in order to check the incidence of drop out from school among girls in the Tea Estate Schools. Justification of the StudyThis study was done because in the recent past there has been increasing cases of girls dropping out of school in the Tea Estate Primary Schools in Kericho County. The study forms a basis for solving problems and finding lasting solutions to this problem of girls dropping out of school.Significance of the StudyThe research findings on the factors leading to drop-out among girls in the Tea Estate Schools will provide useful information to the youth in the county. The study pays attention to factors related to gender disparity which affects access and retention of girls in primary schools in Kericho County.

2. Literature Review

- Chege and Sifuna [3] observed that peer group, if not guided, can lead to devastating results like engaging in drugs, substance abuse, early sexual affairs and spread of HIV/AIDS. The problem of school pregnancies is related to rape and sexual harassment, Mutamba, [15] points out that there are reported cases of girls between 14 and 18 years dropping out of school every year due to pregnancy.Faluma and Sifuna [7] attribute high drop-out among girls due to pre-marital pregnancies which is characterized by frequent sexual harassment particularly in public primary schools.The National Policy of Education in MOEST [10] requires that girls who are pregnant should be enrolled back to school after delivering. However, this is a challenge due to cultural backgrounds and the parents may be demotivated to take girls back to school. Epstein [6] attributed drop-out of girls from school to bad peer pressure, bad vices like drugs, laziness on the side of students and child labour. There are multiple ways researchers measure the effects of women’s education on development.Typically, studies concern themselves with the gender gap between the education levels of boys and girls and not simply the level of women’s education. This helps to distinguish the specific effects of women’s education from the benefits of education in general. Alan, [1] noted that some studies, particularly older ones, do simply look at women’s total education levels. One way to measure education levels is to look at what percentage of each gender graduates from each stage of school. A similar, more exact way is to look at the average number of years of schooling a member of each gender receives. A third approach uses the literacy rates for each gender, as literacy is one of the earliest and primary aims of education. This provides an idea of not just how much education was received but how effective it was.The most common way to measure economic development is to look at changes in growth of GDP [16]. In order to ensure that a connection holds, correlations are analyzed across different countries over different periods of time. Typically the result given is a relatively steady average effect, although variation over time can also be measured. The benefits of education to an individual can also be analyzed. This is done by first finding the cost of education and the amount of income that would have been earned during years enrolled in school. The difference between the sum of these two quantities and the total increase in income due to education is the net return [12]. However this study will focus on the main causes of girls dropout in the Tea Estate Primary Schools in Kericho County.

3. Research Methodology

- The study adopted descriptive research design. According to Lovell and Lawson [8] descriptive research is concerned with conditions that already exist, practices held, processes of past and on-going and trends of development. Descriptive design is most appropriate when the purpose of study is to create a detailed description of an issue, [13]. Drop-outs among girls in public primary schools are practices and conditions that already exist, making the design appropriate for the study. This study therefore focuses on factors that make girls to drop out of school in Tea Estate Primary Schools in Kericho County.The study was done in the Tea Estate Primary Schools in Kericho County. The total population for this study was 2020 respondents which included 20 head teachers, 200 teachers and 1800 girls. According to the records available in the County Education Office (2013) there are 20 Primary Schools in the Tea Estates with a population of 1800 girls, 200 teachers and 20 head teachers. The accessible population is girls of upper classes (standard four to eight). This was purposely selected because many of the girls in these classes are in adolescence period.Stratified Random Sampling was used to select schools per zones where the girls came from. Stratified sampling is suitable when dealing with heterogeneous sub-groups like schools.The instruments used were questionnaires and interviews. Data was coded and perused to remove outliers or missing values and categorizing manuals according to the questionnaires. Items were analyzed using Frequency Distribution Tables and Percentages. Simple descriptive statistics such as percentages have an advantage over more complex statistics since they can easily be understood especially when making results known by a variety of readers. The coded data were then transferred to a computer sheet and processed using Statistical Packages for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 17. During the research study the name of the respondent or interviewed person was kept secret. It was not written anywhere. The information received from the respondent was not disclosed to anybody else or published in public notices for people to see. There was no discrimination of gender or ethnic backgrounds. A person interviewed was told that information received was not to be used to victimize anybody but just for educational purposes. No physical or psychological harm would be inflicted.

4. Results

- Characteristics of the respondents The respondents who took part in this study were head teachers, class teachers and pupils of tea estate primary schools. The results of the study revealed that 60(83.3%) of the respondents aged between 10-20 years were pupils, 2(2.8%) were class teachers who have served in the school for shorter period. Most respondents in the age bracket of 31-40 years were head teachers and their deputies. This showed that for one to be a headmaster he/she must have served in the school for some time to guarantee promotion. This was showed by 8.3% of the respondents. Those who aged 40 years and above were mainly head teachers. They constituted 5.6% of the respondents. This is in agreement with Epstein (2013) where he asserted that for one to head a school he or she should be a mature person.Length of time as a head teacher/class teacherThe research study showed that 6.9% have served in the school either as head/class teacher for 2-5 years. Most of the class teachers served in this period, 5.6% had served for 6-10 years and 5.6% had served for 11 years and above. All were head teachers. It means that for one to be a head teacher he/she must have served for at least 10 years. Most respondents were pupils and they represent 81.9% of the total respondents. Records of girls who have dropped out of school

|

| Figure 1. Causes of girls drop-out in school |

5. Summary, Conclusions and Recommendations

- The major cause of girls’ drop-out is early marriage as it was agreed by 41.7% of the respondents while 33.3% of the respondents argued that the drop-out is caused by early pregnancies. Separation of parents, gender discrimination and poor family background are other causes of girls’ drop-out in school although it was argued by small size of the respondents (8.3% each). ConclusionsGirl child has been vulnerable to; Socio-cultural factors, such as school based and personal factors than the boy child. But socio-cultural factors were the ones with greater impact on girl child stay from school. RecommendationsSchools in the Tea Estates should provide pupils with lunch to reduce exposure to externalities, like rape cases and sexual harassments.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML