-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Education

p-ISSN: 2162-9463 e-ISSN: 2162-8467

2017; 7(5): 83-95

doi:10.5923/j.edu.20170705.01

Shaping Students’ Attitudes towards Business Ethics and Corporate Social Responsibility: Education Versus Personal Perspectives

Cecilia Chirieleison, Luca Scrucca

Department of Economics, University of Perugia, Perugia, Italy

Correspondence to: Cecilia Chirieleison, Department of Economics, University of Perugia, Perugia, Italy.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2017 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Business ethics and corporate social responsibility education is typically considered one of the main determinants of executive attention to ethical decision making, commitment to stakeholder issues and corporate citizenship awareness. However, some scholars also highlight the role of individual level factors and beliefs in shaping students’ future behaviours. The main purpose of this research is to compare the impact of business ethics and corporate social responsibility education with that of personal perspectives on students’ attitudes. Three aspects are taken into account: the expectations of business responsibilities, the propensity to act as a responsible consumer, and behavioural intentions as a future employee. This exploratory study provided the administration of a research questionnaire to a sample of 200 undergraduate students. The statistical analysis reveals that while education has a positive, although limited impact, a strong relationship exists between personal perspectives and students’ attitudes.

Keywords: Corporate Social Responsibility, Business Ethics, Higher Education, Universities, Department of Economics, Italy

Cite this paper: Cecilia Chirieleison, Luca Scrucca, Shaping Students’ Attitudes towards Business Ethics and Corporate Social Responsibility: Education Versus Personal Perspectives, Education, Vol. 7 No. 5, 2017, pp. 83-95. doi: 10.5923/j.edu.20170705.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- In recent years, the growing transparency demanded by the financial markets and public opinion, a series of corporate scandals in important multinational enterprises (MNEs), and the growing demand for social responsiveness to a multiplicity of stakeholders have contributed to push the entire business community towards a heightened commitment towards business ethics and corporate social responsibility. This results in the need to offer students an overview of all the responsibilities of business [30]. Consequently, in the last few years we have seen a widespread tendency towards an increased number of both undergraduate and postgraduate courses devoted to business ethics and corporate social responsibility (CSR) ([14]; [45]; [52]; [69]). This growth has been both quantitative and qualitative. Indeed, the number of courses offered by Higher Education Institutions (HEIs) has increased. In parallel, the range of topics is widening, covering now a great variety of issues, including sustainability, business and society, globalization, corporate governance and the environment ([69]; [72]). The academic literature has addressed the issue of how, and to what extent, business ethics and CSR education plays a critical role in shaping the attitudes and future behaviour of students ([21]; [25]; [29]; [58]) and, therefore, executive attention to ethical awareness and corporate citizenship awareness ([1]; [18]; [19]; [24]). However, various studies have questioned the effectiveness of business ethics and CSR education ([35]; [72]), highlighting the importance of other factors influencing student attitudes, such as age, gender, religious orientation and personal ethical perspectives ([35]; [71]). In particular, some authors claim that undergraduate education arrives to a point when students’ values and opinions have by a large extent already been established ([48]; [55]). Therefore, while dedicated education would definitely have a positive effect on student attitudes, they are much more influenced by their previous beliefs. In this framework, the present research has the main aim of contributing to the debate. The purpose is providing data that allow for a comparison of the impact of personal perspectives versus that of business ethics and CSR education on students’ future attitudes. Three main issues are taken into account: expectations of business responsibilities, the propensity to act as a responsible consumer and behavioural intention as future employee. From a methodological point of view, firstly the quantitative aspects of business ethics and CSR education is assessed by means of a questionnaire survey administered to a sample of 200 undergraduate students. Following this, the students’ personal perspectives on these issues are evaluated. The second part of the analysis is dedicated to framing the students’ attitudes towards business ethics and corporate social responsibility. Finally, using regression analyses and independent sample t-tests, a comparison is made between the influence of the quantity of education and their personal perspectives on student attitudes. As the Department of Economics of the University of Perugia (Italy) is the context for this exploratory study, the results will also contribute to the limited literature in the area of business ethics and corporate social responsibility education in an Italian setting. The remainder of the paper is structured as follows.Firstly, a literature review on business ethics and CSR education is presented, with particular regard to effectiveness and limits in shaping students’ attitudes. Here we also present an overview of the provision of business ethics and corporate social responsibility education in Italian universities. Thirdly, the research methods are outlined, along with the context of the business ethics and CSR educational offer at the Perugia University Department of Economics and the survey sample. Fourthly, the research results are presented and discussed. Finally, the conclusions are outlined, highlighting the implications, limitations and directions for future research.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Ethics and CSR Education: the Effects on Students’ Attitudes

- In recent years, business ethics and CSR education have attracted increasing attention in academic literature, and have become of growing interest to the practitioner [68]. One of the reasons for this development lies in the belief that a more in-depth education on such issues could positively influence the sensitivity of business to such themes in the future. The quantity and quality of business ethics and CSR education today could be one of the main determinants of future executive attention to behavioural ethics in organizations ([1]; [27]; [67]), ethical decision making processes ([49]; [65]), and a commitment to stakeholder issues and corporate citizenship awareness ([17]; [19]; [22]; [45]). Moreover, the recent global financial crisis, the growing number of corporate scandals, increasing stakeholder pressure for more responsible corporate behaviour, and the rising expectations for corporate citizenship in public opinion, have enhanced the awareness of the importance of business ethics and CSR education in guiding the behaviour of future business leaders [40]. In response, there has been a tendency towards a widespread growth in the importance of business ethics and CSR in economics and management education, at both the undergraduate and postgraduate levels ([14]; [51]). Currently many international HEIs offer courses dealing with business ethics and corporate social responsibility ([24]; [46]; [54]), while under these two important umbrella themes other subjects are also progressively emerging, such as sustainability, stakeholder management, ethical finance, and corporate social reporting ([14]; [52]; [69]). Thus, education in these fields is moving towards a cross-disciplinary approach [54].In this framework, various studies, using a variety of both quantitative and qualitative approaches, have attempted to examine whether, how, and to what extent business ethics and CSR education is effective in shaping student beliefs, attitudes and behaviours ([20]; [30]; [58]). Many researchers have found a positive relationship with moral recognition and moral reasoning ([21]; [27]; [38]; [72]), ethical awareness ([9]; [38]; [41]); moral courage [46], student values and opinions ([63]; [75]), and the perception of business’ role in society [76]. Business ethics and CSR education seems to be able to influence not only features linked to students’ future professional skills, but also other aspects of their lives, enhancing their propensity to act as better citizens in the community, for example as responsible consumers. On the other hand, the literature highlights the existence of various conditions that could affect the effectiveness of business ethics and CSR education. Some of these are under the influence of HEIs, such as the objectives of the course ([62]; [74]) or the teaching methods [62]. Others are beyond the control of the educational institution, such as the students’ gender ([7]; [36]; [55]; [58]; [71]), age [7], nationality [39]; religious orientation ([3]; [6]; [16];[43]) or previous experience in community service projects [75].While the literature is largely unanimous in recognising that business ethics and corporate social responsibility courses are effective in shaping student skills and future behaviours [38], there are also dissenting opinions. Various theoretical and practical approaches see complementarities between economic, social and ethical responsibilities. Despite this, some scholars highlight that business education generally is still focused on a traditional vision, often implicitly maintaining Friedman’s [26] view of maximising profit as the core responsibility of the firm [30]. Thus, undergraduate and postgraduate business studies might even inspire unethical theories, and emphasize the importance of shareholder benefits at the expense of stakeholders ([4]; [28]; [53]). Some authors demonstrated that, in the perception of students, the importance of the shareholder model in comparison with the stakeholder model grows during the undergraduate education. Paradoxically, at the end of their degree they are less sensitive to corporate social responsibility and business ethics than at the beginning [37]. Moreover, some authors claim that personal perspectives and opinions could be difficult to change through university education: ([33]; [40]) given that character development has already occurred by the time an individual reaches college age, it is too late to reshape ethical values [55]. From this perspective, a single or limited number of classes is not enough to change attitudes built earlier in somebody’s life [48]. Consistently, character, personality, personal values, and cultural orientation, established regardless of education, have been studied as determinants of students’ future attitudes ([39]; [48]), suggesting that it would be opportune to offer education on business ethics and corporate social responsibility before college age, acting before these convictions are completely formed. Various studies suppose that personal perspectives could have a greater weight in shaping students’ attitudes, than CSR end ethic courses ([8]; [48]; [71]). However, little research has been devoted to the comparison between the impact of education and that of previous beliefs on students’ orientation and future behaviours.In this framework, the main purpose of the research is to compare the impact of personal perspectives and education on students’ future attitudes, considering three aspects. Firstly, attitudes towards the business’ role in society and expectations in terms of a firm’s responsibilities ([10]; [11]); secondly, attitudes in terms of the propensity to act as a socially responsible consumer ([5]; [44]; [47]; [50]; [60]); thirdly, attitudes as future employees with particular regard to the job search ([31]; [56]; [57]; [70]).

2.2. The Italian Context

- Having been little studied in international literature, Italian CSR and business ethics education was chosen as research field. In general, Italian universities began to introduce courses devoted to business ethics and corporate social responsibility later than the US, where they had begun to spread in the 1970s, and became common in the 1980s [15]. Even compared to the rest of Europe, Italy has lagged behind, hosting the first courses around the 1990s ([34]; [74]). In the ‘70s, business ethics and CSR courses have been introduced thanks to the personal commitment of individuals in the faculties. Progressively, and especially in the new millennium, significant changes in the social and economic context in Europe and Italy led to a gradual evolution. Consequently, HEIs increased institutionalization of such courses, with a wider integration in undergraduate and postgraduate curricula (ICRS 2009).Today, while some courses relating to business ethics and corporate social responsibility are spread between departments of political science, engineering and agricultural science, most of them are concentrated in economics and management departments [13]. To better understand this context, it is necessary to clarify that while Italian universities were traditionally divided into faculties, the legislative reform of 2010 replaced these with departments, which undertake both research and teaching in a single organizational structure. It is worth noting that in Italy, in general, each university only has one department that deals with subjects involving the economy and business. The typical – but not unique – designation adopted is Department (formerly Faculty) of Economics, which usually encompasses both teaching and research activities, dealing with a wide range of themes that go beyond economics, including management, business administration, accounting and finance. From a quantitative point of view, even if only a limited amount of research has been conducted in this field ([12]; [13]; [32]; [34]; [59]), it seems clear that in the last few years the number of business ethics and CSR courses in Italian HEIs has grown rapidly. Chirieleison and Scrucca [13] conducted the most recent study. They took into account all economics and management departments in private and public universities and surveyed their entire educational offer based on their official web sites in order to identify all those courses that have business ethics or CSR as their main focus, as indicated by the course title. All cultural areas were included (i.e. law, finance, etc.), not only those directly related to economics or management. In absolute terms, as many as 291 courses were found, 65% at the MSc level and 34% at the bachelor level. While methodological differences do not permit a direct comparison, it appears that a large growth can be observed compared to previous researches, which counted just a few dozen courses ([32]; [34]; [59]). Moreover, this latest research confirms some tendencies presented in other studies, which appear to strongly characterize the Italian context. Firstly, most of the courses are part of postgraduate degrees, which implies that business ethics and CSR are seen as a postgraduate subject area, more than a basic competence for undergraduate students. Secondly, most courses are mandatory, at both the bachelor’s and MSc levels, indicating that these competences are being increasingly seen as an essential part of the students’ education. Thirdly, with regard to the main subjects, a high number of specialized courses emerge, with a wide variety of labels and topics, as compared to a small number of courses dedicated to conceptual frameworks. Consequently, the educational offer tends to be fragmented and lacks an overall vision ([13]; [34]).

3. Methodology

- The main purpose of this research is to compare the impact of education and personal perspectives upon students’ attitudes. An exploratory study has been conducted on the Department of Economics of the University of Perugia (Italy). The next paragraph provides an analysis of the educational offer of the Department, aimed to evaluate whether, and to what extent, the programs deal with business ethics and CSR issues. The analysis was conducted throughout the academic year 2015/2016, using the University web site, Department web sites, degree brochures and related documents as the main data sources. Firstly all the necessary information on the institutional activities of the Department was collected. Secondly, a database of all courses offered in the academic year 2014/2015 was created, identifying those that have business ethics or CSR as their primary objective (as indicated by the course title). Thirdly, the teaching programs of all other courses were analysed, selecting those dealing with issues relating to business ethics and/or CSR.In the paragraph that follows, the survey sample of students is presented. The research was limited to undergraduate students, taking into account that this could still be considered a highly formative stage in the development of awareness of ethical and social issues, as at the postgraduate level most personal opinions and attitudes are already set in place [71].The method provides four main steps.The first step is the measurement of the ethics and CSR education received by the student from a quantitative point of view, referring to both courses entirely focused on these issues and those that merely embed them as part of a different main theme. Obligatory and elective courses have been kept separate, in order to assess whether they have a different impact on student attitudes. A summary value of "Quantity of education" is then calculated. The second step provides for an evaluation of the students’ personal perspectives, asking them to declare their personal opinion about the importance assigned to several aspects related to business ethics and corporate social responsibility, regardless their studies. A summary value of "Overall importance" is then calculated. Once it has been verified that this is independent from the "Quantity of education" on business ethics and social responsibility by means of a regression analysis, the "Overall importance" is considered the result of the students’ personal beliefs. The third step is the investigation of three key aspects of student’s attitudes: the importance they recognise to the different aspects of the firm’s economic, social, ethical and discretional responsibility, the support they would be willing to provide to responsible firms as consumers, and their behavioural intentions as future employees. For each of these aspects, the students have been asked to rate various sentences, which have then been grouped in homogeneous subscales. Then, a descriptive statistic has been performed. Finally, the fourth step of the research involves the performance of a regression analysis and independent sample t-tests, with the aim of estimating whether students’ attitudes vary as a function of the quantity of education and/or as a function of personal beliefs. This allows evaluating which of the two factors should be considered most influential.

3.1. Ethics and CSR Education at the Department of Economics of Perugia University

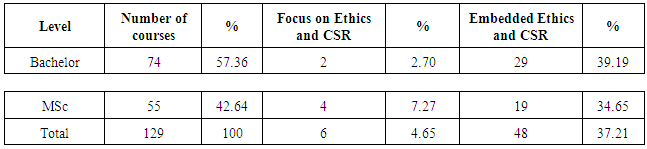

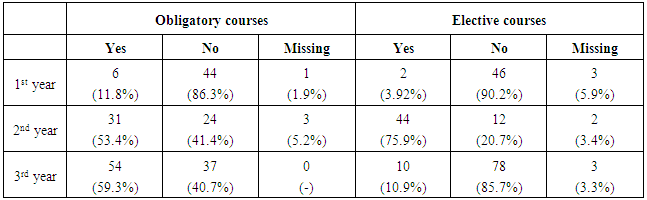

- The University of Perugia is one of the oldest ones, not just in Italy, but also in the world. According to some estimates, it is numbered among the first twenty, with its origins in the Middle Ages. As typical in the Italian context, the Department of Economics deals with both research and teaching on a wide spectrum of topics, covering not just economics, but also management, finance, business administration and accounting [12]. Therefore, this department was chosen as a case study as it is fully representative of Italian departments of economics and management. Moreover, while Perugia cannot truly be considered one of the largest Italian universities, the Department of Economics has its own centre for CSR issues (the Research Centre for Law Studies on Consumer Rights) and it is also associated with Nemetria (a well-known Italian non-profit organization that has as its main objective the study of the relationship between ethics and economics). Thus, it can also serve as a good term of comparison in benchmarking analysis with other departments.In the educational offer for the academic year 2015/2016, the Department of Economics offered a total of 129 courses, 57.36% on Bachelor’s degrees and 42.64% on MSc degrees. Considering the official course programs published on the Department web site, it was possible to identify those entirely focused on ethics and CSR and those, which embed them within a different main theme (Table 1.).

|

3.2. Sample and Data Collection

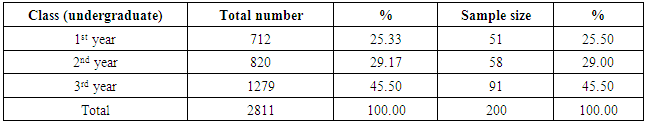

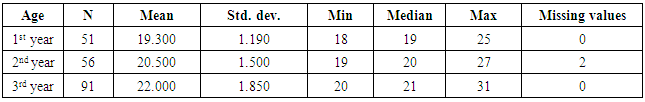

- The survey was conducted during the first Semester of the academic year 2015/2016. The questionnaire was administered during lessons to a random sample of 200 undergraduate students at the Department of Economics, enrolled in the various Bachelor’s degrees that make up the educational offer. The sample took into account the overall distribution among students by enrolment year, as indicated in Table 2.

|

|

4. Results

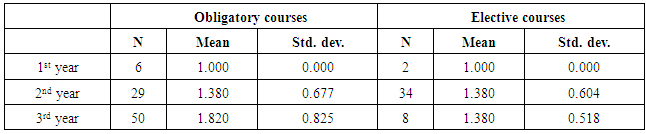

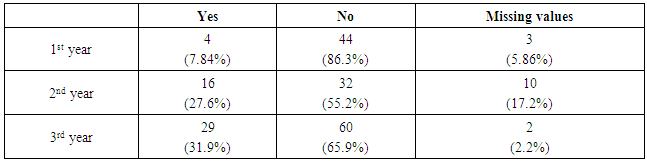

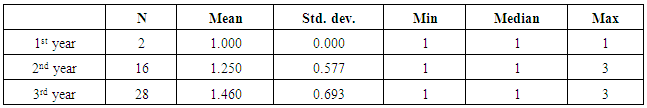

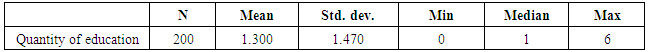

4.1. The Quantitative Aspects of Business Ethics and CSR Education

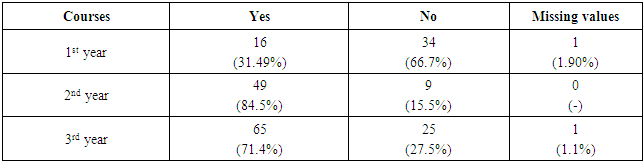

- The first part of the survey has the objective of measuring the quantitative aspects of ethics and CSR education at the Department of Economics of Perugia University. This aspect cannot be evaluated by simply taking into account the supply side for two main reasons.Firstly, mandatory courses differ from a degree course to another, and the students - whatever degree course they are enrolled in - are allowed to choose a number of elective courses. Thus, even within the same degree, not all students attend the same courses.Secondly, among the courses dealing with business ethics or CSR provided in the educational offer, only a small number are completely focused on these issues, while a large majority embed them within a different thematic focus (i.e. an ethical finance module in a corporate finance course). In the latter case, regardless of the teaching program, students may not even perceive that the course deals with business ethics or CSR, if it is not mainstreamed during the lessons. Thus, the supply side of the educational offer may significantly differ from that perceived from the students’ demand side. To this end, the students were first asked if they had ever taken any courses that entirely or in part deal with business ethics or CSR (Table 4.). Only among first year students did a majority respond negatively. However, the survey was conducted during the first semester, which means that the first year students had only been able to attend a limited number of courses. Moreover, first year courses typically focus on basic economic concepts. On the other hand, in the second and third year, a large majority of students (84.5% and 71.4% respectively) had taken at least one course that dealt to some extent with business ethics or CSR.

|

|

|

|

|

|

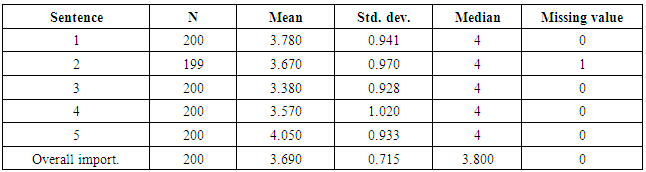

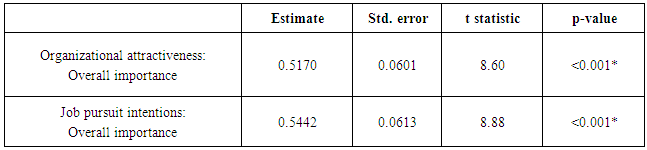

4.2. Evaluation of Student’s Personal Perspectives on Business Ethics and Corporate Social Responsibility

- The second research step aims to evaluate the students’ personal perspectives on the importance of ethics and CSR in the business context, regardless of the education received. To do so, students were asked to express their personal opinion, regardless of received education, rating five sentences derived mainly from Etheredge [23] and Singhapakdi et al. [64] on a Likert type scale (from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree):Ÿ sentence 1: Being ethical and socially responsible is the most important thing a firm can do;Ÿ sentence 2: The ethics and social responsibility of a firm are essential to its long-term profitability;Ÿ sentence 3: The overall effectiveness of a business can be determined to a great extent by the degree to which it is ethical and socially responsible; Ÿ sentence 4: Business ethics and social responsibility are critical to the survival of a business enterprise;Ÿ sentence 5: Business has a social responsibility beyond making a profit.All the items have been averaged to obtain the single “Overall importance” variable (Table 10.).

|

|

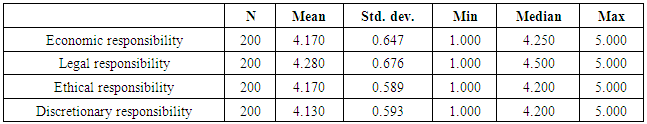

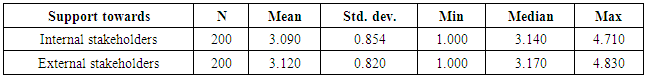

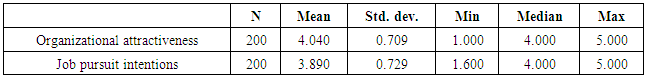

4.3. Assessment of Students’ Attitudes towards Business Ethics and Corporate Social Responsibility

- To assess student attitudes, three aspects have been taken into account.The first aspect regards attitudes towards the responsibilities of the firm. In order to integrate corporate social responsibility and ethics in a single framework, reference was made to Carroll’s widely known four dimension pyramidal model [10]. The students were asked to rate various sentences derived mainly from Maignan & Ferrell [42] on a Likert type scale. Then, the sentences have been grouped in four subscales and associated with the economic, legal, ethical and discretionary responsibilities of the business. The results are shown in Table 12.

|

|

|

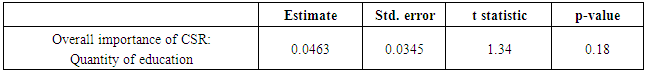

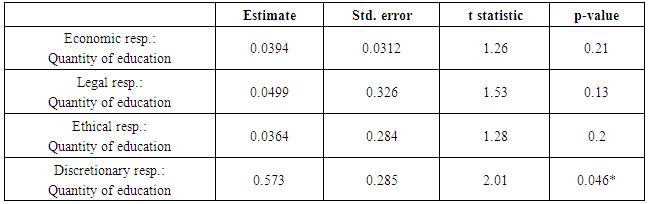

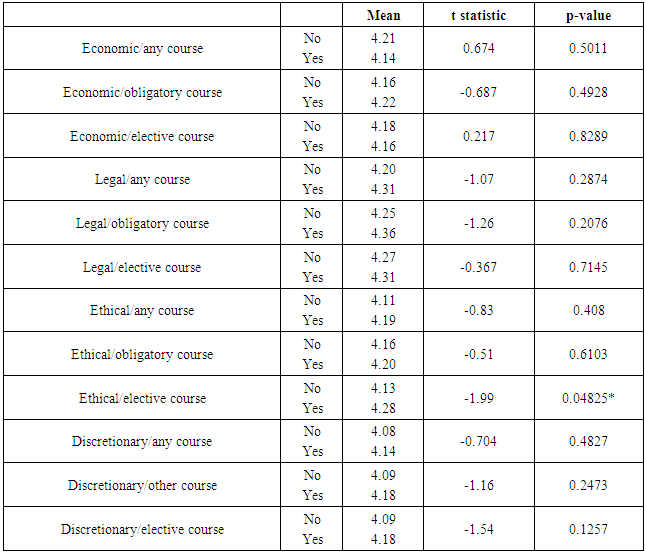

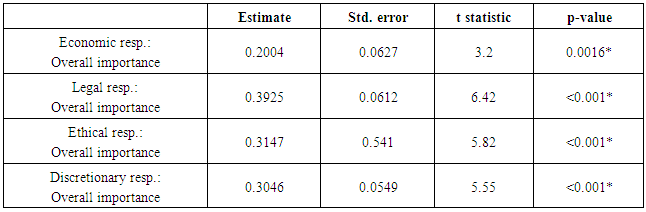

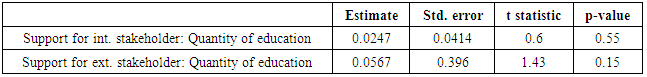

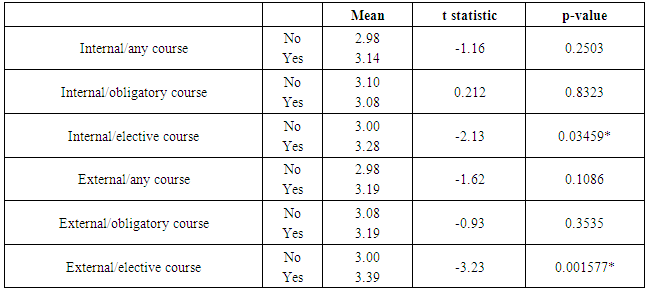

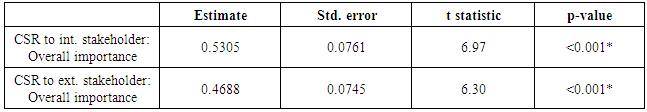

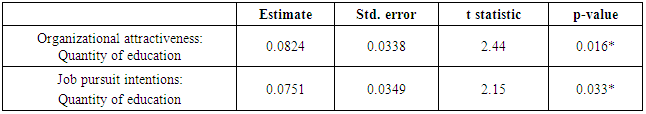

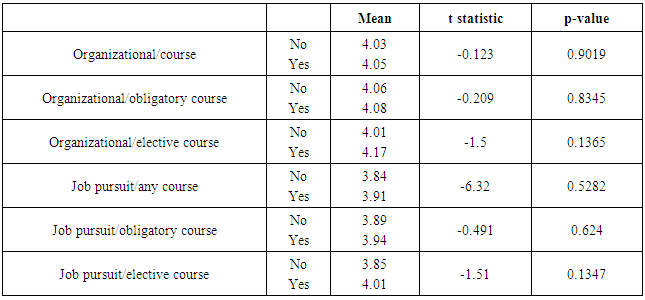

4.4. Shaping Students’ Attitudes: Education or Personal Perspectives?

- The final step of the research aims to evaluate whether student attitudes towards business ethics and corporate social performance are influenced by the quantity of education received on these issues and if this factor is more or less influential than their personal beliefs. To this end, regression analyses and independent two-sample t-tests were performed, using both the "Quantity of education" as calculated in Table 9. and the "Overall importance" as calculated in Table 10. as independent variables.Considering the first aspect (namely, the attitudes towards the firm’s responsibilities) the regression analysis shows that the quantity of education affects the importance assigned to the four issues to a limited extent (Table 15.).

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

5. Discussion

- In recent decades, there has been a progressive tendency towards a widespread growth in the importance of business ethics and corporate social responsibility education, at both the undergraduate and postgraduate levels ([45]; [52]; [69]). The recent global financial crisis, and the increase in the number of corporate scandals, have enhanced the awareness of the importance of education in guiding the behaviour of future business leaders [19]. Teaching business ethics and corporate social responsibility to economics and business students is perceived to contribute towards shaping the attitudes of future managers, positively influencing their future ethical responses and social commitment [58]. While many empirical studies seems to confirm this relationship, some authors claim that economics and business students are still surrounded by a cultural environment, that often promotes a shareholder value based view of the firm, grounded in the cult of profit maximization ([30]; [37]). Therefore, to be capable of influence, business ethics and CSR should be strongly mainstreamed into degree curricula, and not promoted as isolated courses ([22]; [45]; [61]; [66]). Moreover, some scholars argue that teaching business ethics and CSR at the bachelor lever is too late to be effective. In fact, by this stage student values and opinions have to a large extent already been established, and are difficult to reshape through university education ([33]; [40]; [55]).In this framework, with reference to the still little studied Italian context, this paper contributed to explore how students’ personal perspectives on business ethics and corporate social responsibility influence their attitudes. Then a comparison was established with the effect of the quantity of ethic and CSR education. The results of this exploratory study provide at least three important contributions.Firstly, in relation to the quantity of education received, the empirical data appears to show that the students at times fail to recognise business ethics and CSR education when embedded in a course focused on other topics. This fact implicitly suggests the existence of a threshold of visibility for effective teaching of these issues. Secondly, as emerges in the prevalent literature, the finding supports the idea that business ethics and CSR courses can be effective in shaping students’ attitudes, but only to a limited extent, and with particular reference to a greater number of elective exams. Isolated courses and fragmented programs, which are typical of the Italian HEIs framework, demonstrated to have a poor level of effectiveness.Thirdly, personal opinions and perspectives have been shown to have a greater relation with student attitudes toward business ethics and CSR. This validates the idea that individual level factors and beliefs, accrued before (and regardless of) undergraduate studies, significantly contribute to shape their behaviours as citizens and as future corporate managers and executives [48].

6. Conclusions

- Branching out from this specific case study, some final considerations can be drawn. Even if this is only an exploratory study and further confirmation is necessary, it seems that only a high quantity of dedicated CRS and business ethics education is effective in reshaping students’ attitudes. This suggests the opportunity of carefully designing curricula, for an effective learning. Moreover, personal opinions and previous beliefs remain very important in shaping the future attitudes of students, despite a high quantity of CSR and business ethics education. Thus, it could be beneficial to begin teaching these issues before university studies (in example, at high school level). With specific reference to practical recommendations, this study can potentially be useful for managers involved in hiring employees for positions requiring ethics and CSR competences. In the future, recruitment policies will probably take ethics and social attitudes into a greater account, as they are perceived acting as a catalyst, to stimulate corporate citizenship. Typically, during the selection process, and particularly in the case of recent graduates, significant importance is given to the university curriculum. Based on the findings of this paper, recruiters should also take into account personal perspectives and beliefs. In fact, they appear to shape student attitudes more than education. Thus, the judgment on the curriculum vitae should be complemented by a careful evaluation of the candidate's effective values and propensities.While this paper has provided fruitful initial insights into the comparison between education and personal perspectives on student attitudes, as well as the framework of business ethics and CSR education in Italy, it does however have a number of limitations. First, the findings stem from a single department investigation. This fact implies that the results cannot be readily generalized, although it might also be argued that the institution in question can be considered representative of the Italian context. With regard to education on business ethics and CSR, only the quantitative aspect was evaluated, while the quality of education could also have a strong influence on its effectiveness. Moreover, the indicators used to measure personal perspectives could be improved, as this was evaluated by taking into account self-disclosed student information, which may not be entirely reliable. At the same time, a wider and more detailed range of aspects could be taken into account when assessing student attitudes towards business ethics and corporate social responsibility. Following this research, it is possible to suggest some aspects deserving further investigation. As this is an exploratory study, additional data are necessary to confirm the extent of personal beliefs’ impact on students’ attitudes. Moreover, additional research is required to determine the differential influences of an education based on standalone business ethics and CSR courses, and courses that only embed them in different core arguments.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- The authors wish to thank Ludovica Ciccone for the help in processing the data.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML