-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Education

p-ISSN: 2162-9463 e-ISSN: 2162-8467

2017; 7(3): 39-46

doi:10.5923/j.edu.20170703.01

Racial Differences in Contributing Interactions and Activities to Student Character Development

Michael D. Thompson1, Brandon H. Common2

1Office of Institutional Research & Planning, Illinois Wesleyan University, Bloomington, IL, USA

2Dean of Students Office, Illinois Wesleyan University, Bloomington, IL, USA

Correspondence to: Michael D. Thompson, Office of Institutional Research & Planning, Illinois Wesleyan University, Bloomington, IL, USA.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2017 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

This study examines students’ engagement with institutional resources and its bearing on student character development within a small private liberal arts setting. Differences between racial groups, as well as men and women are also investigated. One highly selective liberal arts institution is utilized as a case study within the context of Astin’s [2] input-environment-outcome (I-E-O) model. Data elements from 411 student participants in their fourth undergraduate year were extracted from merged longitudinal databases that included matching student responses from the 2007 and 2010 Student Information Forms (SIF) and the 2011 and 2014 College Senior Surveys (CSS). Although the results of the study confirm many conventional understandings regarding student character development, they also raise larger questions concerning the effectiveness of small liberal arts institutional environments in contributing to its enhancement. Significant differences between White and Black students regarding institutional resources also raise questions concerning the effectiveness of interactions and activities for diverse populations.

Keywords: College Students, Character Development, Racial Differences

Cite this paper: Michael D. Thompson, Brandon H. Common, Racial Differences in Contributing Interactions and Activities to Student Character Development, Education, Vol. 7 No. 3, 2017, pp. 39-46. doi: 10.5923/j.edu.20170703.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Character development as an outcome of the undergraduate experience has been well documented in higher education throughout its history and continues to be prevalent in college and university mission statements today. This is especially true at liberal arts institutions, which tend to promote, facilitate, and deliver the resources related to the development of attributes that commonly define character. Many character-related attributes historically derived from the religious doctrines of sectarian affiliated institutions, which emphasized values that often included an understanding of social and cultural norms, a consideration for others, spiritual sincerity, and a personal code of moral and ethical principles [5, 11, 23, 30, 40, 41]. A number of changes have taken place in higher education over the past several decades that have diminished interest in character development as a primary student outcome. A combination of changes in institutional priorities and demographics resulted in decreases in the emphasis placed on the development of various character attributes, altruistic interests, and civic engagement as part of the undergraduate experience. Additionally, many institutions began to emphasize professional and vocational preparation, which place less concentration towards the cognitive, ethical, and moral development of students [2, 3, 6, 7, 23, 30, 34].In recent years, however, character development has garnered a renewed interest. This renewal is partly due to campus climate issues (e.g., race, gender, sexual orientation, political stance) across the country that have caused individuals both inside and out of the academy to question the civility of today’s college students. Additionally, many higher education scholars have identified global transgressions within the corporate, environmental, financial, and political sectors of society as matters of character, social responsibility, and equity. Examples include the ability to address challenges concerning access to education and health care, global warming, international relations, and the economy [6, 7, 9, 28]. The current study’s examination of character development and its contributing student engagement resources is based on a similar model proposed in Astin and Antonio’s [3] investigation regarding the impact of college on character. In their research, character is defined as “…values and behavior as reflected in the ways we interact with each other and in the moral choices we make on a daily basis” [p.4]. Six measures were chosen to address student character development: civic and social values, cultural awareness, volunteerism, importance of family, religious beliefs and convictions, and understanding of others. Within these six measures, Astin and Antonio’s results established that students’ engagement with peers from different racial groups, exposure to courses on cultural and ethnic differences, community service participation, leadership training, internship participation, attending religious services, and faculty support were predictive of character development.Several studies support Astin and Antonio’s findings. For example, students’ involvement with faculty, ethnic and women’s studies, volunteer service, leadership training, internships, and socializing with peers from different racial/ethnic groups have all been noted as significant contributors to student character development [21, 23, 24, 26, 30, 35, 39]. There is also ample evidence concerning the strong relationship between students who observe religious traditions and/or attend religious services and their developmental increases both personally and socially, including the enhancement of character [2, 4, 25].A recent study utilizing a similar model presented in Astin and Antonio’s examination of student character development investigated 11 variables for their predictive qualities concerning character development within a small private liberal arts institution. Students’ predisposition to character development, attending religious services and racial/cultural workshops, participating in internship programs, and interactions with faculty and peers from a racial/ethnic group different from their own were found to be significant predictors of student character development. Community service, taking ethnic and women’s studies courses, leadership training, and gender yielded non-significant results [40].One missing element in the aforementioned studies concerning student engagement and its relationship to character development is an examination of differences, if any, between various racial groups. Over the last 20 years, empirical research has explored the levels of Black students’ engagement with resources that are consistent with those that enhance character. Broadly this research posits that Black students experience lower levels of engagement than their White peers due to several reasons including campus climates at historically White institutions of higher education which produce environments where Black students are subjected to racial microaggressions [33]. Disaggregating existing literature to explore the differences in engagement based on gender indicate that over the last decade Black women have reported higher levels of engagement in academic and social activities than their male counterparts despite the positive outcomes for this group [1, 18]. These engagement indicators included pursuing academic endeavors outside of class, leadership opportunities, experiential learning activities (e.g., study abroad, internships), and interactions with peers, faculty, and staff [8, 13, 17, 18, 20].Although few studies have juxtaposed the experience of Black women and men to understand why women engage at higher levels, there is a breadth of empirical studies that examine the engagement of Black men. One line of research approaches the issue from a structural perspective by examining how our education systems and institutions of higher education stymie Black male engagement. This approach traces the racialized systems Black males encounter within their K-12 and postsecondary education experiences where Black males are subjected to hyper-surveillance, unwarranted stereotypes, and isolation, significantly contributing to their racial battle fatigue. To what degree and effectiveness do Black males resist racialized structures through maintaining high aspirations is a common line of inquiry [33, 31, 32]. Another line of research explores individual characteristics that impact involvement including how Black males are socialized to place less preference on purposeful college activities (e.g., leadership roles, clubs, organizations) and relationship development (e.g., peer collaboration) and more preference engaging in physical activities, video games, and the pursuit of women [16, 19, 27, 36]. Moreover, as character development continues to garner renewed emphasis, how various racial groups and especially Black collegians engage with character enhancing activities requires further understanding.In summary, it has been well established that students’ undergraduate experiences significantly contribute to their character development. However, it is important to examine which experiences hold particular salience, especially within the context of different demographics and institutional structures. The present study will contribute to the above research on student character development by examining one highly selective liberal arts institution and the effects of its attributed contributions from various institutional resources within the context of Astin’s [2] input-environment-outcome (I-E-O) model. Astin’s I-E-O model was selected for this study because of its proven usefulness in observing student learning and growth (outcomes) as a result of students’ entering characteristics (inputs) and their exposure to institutional resources (environment). The attributed contributions from various institutional resources to students’ character development will be examined, while controlling for students’ predisposition to character building activities and attributes. As noted in previous studies, engagement with institutional resources (e.g., co-curricular and coursework activities, interactions and experiences) has a significant influence on the differential patterns of student learning and growth [2, 30, 38], thus making the I-E-O model particularly useful for the present study.

2. Methodology

2.1. Participants

- This study was based on a sample of seniors at a private liberal arts institution located in the Midwest United States with an approximate enrollment of 1,900 students. Data elements from 411 student participants in their fourth undergraduate year were utilized for the present study. Two senior classes were included in the analysis, representing 37% and 43% of their respective classes. The male population was doubled via weighting procedures, which used the frequency variables (e.g., men = 2) as case weights. This procedure has been noted as an effective tool in eliminating the influence of differential response rates [10]. All subsequent analyses were based on a weighted number of 487 participants (females = 53%; males = 47%), who provided full information on all variables. Approximately 16% of the participants were Students of Color, 2% International and 82% White - a moderate overrepresentation of White students for the institution’s senior classes (78% and 76%, respectively).

2.2. Instruments

- The data elements utilized for the present study were extracted from merged longitudinal databases that included matching student responses from the 2007 and 2010 Student Information Forms (SIF) and the 2011 and 2014 College Senior Surveys (CSS). The SIFs were administered during the student orientation programs of the students’ first year, while the CSS instruments were administered in the final semester of the students’ senior year. All surveys were administered through the Higher Education Research Institute at the University of California - Los Angeles.

2.3. Variables

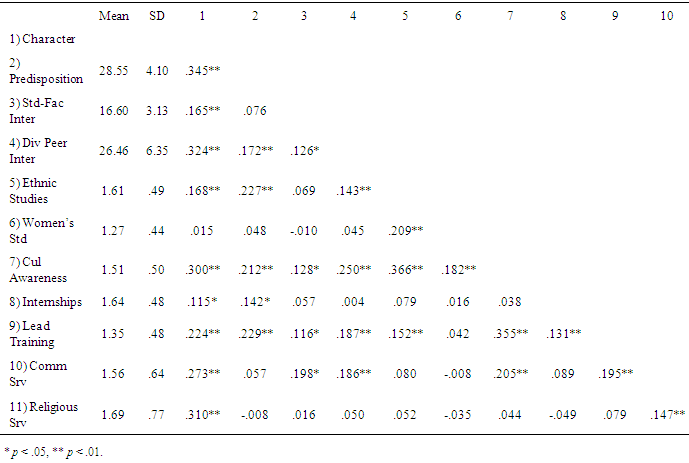

- The present study utilized a composite variable to represent character (dependent variable), which included 14 items related to students’ development, engagement, and the importance they placed in areas concerning family, social justice, civic engagement, and religion. The selected items were taken from the CSS and were largely based on measures derived and validated through exploratory factor analyses in Astin and Antonio’s [3] study regarding the impact of college on character development. In addition, these measures were successfully implemented in a similar study of character development that examined the role and effectiveness of the liberal arts environment in contributing to the enhancement of character [40]. These measures examined character as a conglomeration of attitudes, beliefs, morals, values, and behaviors highly favored in society. A summation of the character items yielded an alpha of .79, with a mean score of 45 (out of 63) and a standard deviation of 6.7.Identified from previous studies, nine resources (independent variables) based on students’ interactions, experiences and activities were identified in the CSS instruments [3, 23, 40]. Student-faculty interaction was examined through an 8-item scale, while interaction with peers from a racial/ethnic group different from their own was assessed via a 9-item scale. The alphas for the scales were .86 and .84, respectively. Seven individual items accounted for attending ethnic and women’s studies courses and workshops, religious services, leadership training, internships, and community service. An 11-item composite variable (alpha = .65) was utilized to control for students’ pre-college engagement in activities and their predisposition (e.g., goals, future plans) concerning objectives related to character development (e.g., family, social justice, civic engagement, religion).

2.4. Research Design and Procedures

- Based on the evidence concerning student character development, the following social, co-curricular, and coursework related areas were included: experiences with peers from different racial/ethnic groups, exposure to courses on cultural and ethnic differences, participating in community service, leadership training and internships, attending religious services, and formal and informal interactions with faculty [3, 40]. Linear regression procedures were used to assess the contributions from various institutional resources to students’ character development, while controlling for students’ predisposition to character building activities and attributes, as well as gender and race. The design of the present study was guided by a set of expectations concerning the significant contribution to students’ character from the following variables:Ÿ Students’ predisposition to character development (input)Ÿ Differential patterns of resource engagement as designated by race Ÿ Participation in religious services (strong affect)Ÿ Formal and informal interactions with faculty Ÿ Interactions and experiences with peers from diverse races and ethnicities (strong affect)Ÿ Engagement in co-curricular and coursework activities

|

3. Results

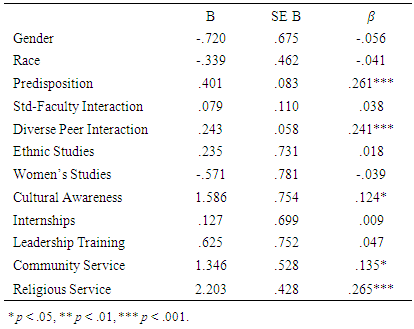

- Linear regression analysis was used to test if institutional resource engagement significantly predicted students’ character development. The results of the regression indicated that five of the 12 predictors explained 33% of the variance (R2 = .33, F (12, 264) = 10.86 p < .001). Student’s predisposition to character development (B = .401, p < .001), attending religious services (B = 2.20, p < .001), attending racial/cultural workshops (B = 1.586, p < .05), performing community service as part of a class (B = 1.346, p < .05), and interactions with peers from a racial/ethnic group different from their own (B = .243, p < .001) significantly predicted student character development. Student-faculty interactions and engagement with internships, ethnic and women’s studies courses, and leadership training, yielded non-significant results, as did gender and race.

|

|

|

|

|

4. Discussion

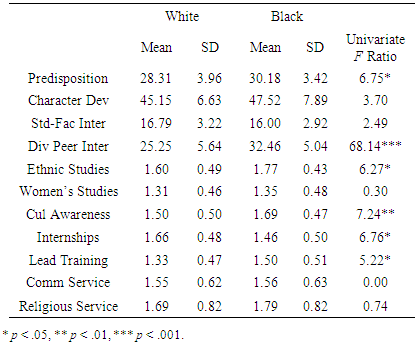

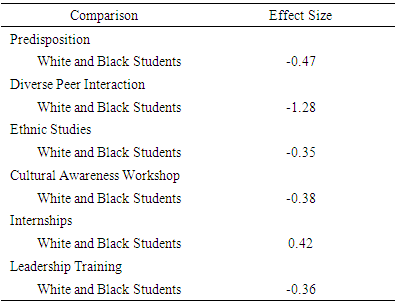

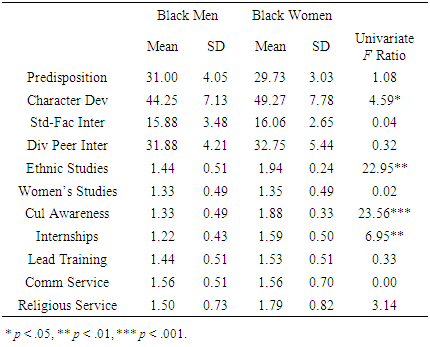

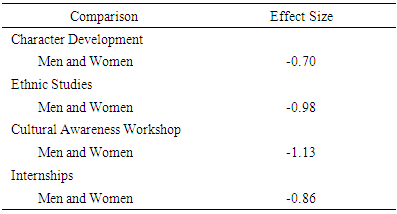

- The findings of the present study provide further evidence concerning the contributions to students’ character development through college interactions and engagement resources. The association between students’ predisposition to character, their commitment to religious services, racial/cultural workshops, community service, and their interactions with peers from a racial/ethnic group different from their own are consistent with the aforementioned research concerning identified predictors of character enhancement [3, 26, 35, 40]. Attending religious service was the strongest variable influencing student character development, which is understandable given the noted significant relationship between students’ religious disposition and character within the aforementioned higher education literature. Similarly, one would also expect students who exhibit a predisposition to character development to show evidence of continued development during their undergraduate experience. This expectation was confirmed in the present study. It is also noteworthy that interactions with diverse peers, participating in community service, and attending a cultural awareness workshop were influential categories towards character enhancement. The significant contributions of these interactions and experiences are consistent with Kuh’s [24] comprehensive assessment of the impact of engagement activities on student learning and personal development.Just as notable as the significant contributions of college interactions and resources on character development, is the absence of influence concerning the remaining educational practices and activities. This is especially true given the academic environment under examination for this study, that is, a small private liberal arts institution. As noted previously, these institutions are characterized and marketed to appeal to students who desire more personal and customized attention, with readily accessible educational opportunities and resources, and close engagement with fellow students. Student-faculty interaction has been documented for decades as a significant contributor to student learning and development, and specifically student character development. However, the formal and informal interaction items examined in the present study did not yield their expected influence. This is an especially surprising outcome, given the institutional resources and expectations that are bestowed upon faculty in this environment (e.g., personal attention, small class sizes, high quality advising). It is possible that student-faculty interaction at this particular college is simply not as strong as would be expected within similar institutions. For example, students may not frequently interact with faculty on activities outside of routine coursework. It is also possible that students at this institution explored certain experiences elsewhere (e.g., emotional support, professional goal assessment) and with different people (e.g., peers, administrators).The results of the present study also revealed failed expectations concerning the positive influence of students’ engagement with a handful of co-curricular and coursework activities (e.g., internships, leadership training, women’s and ethnic studies courses). Difficulties in measuring the benefits of these endeavors include understanding their context and content. For example, students’ level of engagement with these activities may not have been sufficient to provide the expected impact on character enhancement. In addition, if these experiences lacked intellectual challenge, their impact on student learning and growth may be suspect.The final elements that yielded non-significant results were gender and race, which were inconsistent with the differences noted in previous research concerning character-related attributes. One possibility for the lack of variance in the present study may be related to the institution under examination, a very selective college with a fairly homogenous student body. The previous studies noting significant differences by gender and race were observed through larger databases consisting of a more diverse mix of students and institutions. In comparison, the present study was limited in this manner. However, additional analyses were conducted specifically comparing character predisposition, character development, and levels of engagement between White and Black students.An examination of the mean differences between White and Black students revealed significantly higher engagement levels for Black students regarding their interactions with diverse peers, and their participation in ethnic studies, cultural awareness workshops, and leadership training. The diverse peer interaction variable had the largest mean difference and effect size, which may have contributed to Black students’ greater overall character growth as compared to White students, although the mean difference was not statistically significant. Additionally, Black students had a significantly higher predisposition to character than their White counterparts. Participating in internships was the only significant variable where White students reported a higher mean score than Black students.There are several plausible reasons as to why Black students in this study engaged with diverse peers at higher levels than their White classmates. Foremost, the lack of a critical mass of Black students at the institution might make it difficult for these students to engage exclusively in same race activities (e.g., Black fraternities/sororities, professional organizations). Within the higher education literature critical mass has been defined as a level of representation of a marginalized group that brings comfort or familiarity within the education environment [15]. Frequently defined as a percentage of the overall student body, maintaining a critical mass helps to promote inclusion for marginalized groups. A second explanation for increased engagement might lie in the believed value of cross-cultural interaction by Black students. Despite the existing literature suggesting that Historically Black Colleges and/or Universities (HBCUs) provide a more supportive and empowering environment for Black students [1, 12, 22, 29], the fact that these students chose to attend a highly homogenous community may indicate that they sought out an experience with mixed race peers. This is different from White students who might have selected a racially congruent environment because they may place less importance on interacting with diverse peers at high engagement levels. Additionally, Black students might make decisions concerning involvement based on their perceived value of activities that contribute to their overall experience (e.g., student government, study abroad). Subsequently, these choices might unintentionally bring them into contact with different students. Finally, Black students might be more intentional in their interactions with peers from different races and ethnicities because of the belief that it will allow them to better integrate into their environment. It is also important to consider that despite these findings, Black students continue to perceive campus climates at traditionally White institutions as hostile. For this reason, it is important for faculty and administrators alike to continue to convey the importance of diverse peer interactions for all students, especially those in the dominant culture. Additionally, noting the levels at which Black students engage with diverse peers, researchers can seek to better understand the impact of these interactions on students. Examining mean differences between Black men and women revealed consistencies with the noted research concerning Black women’s higher engagement and achievement levels. Black women reported significantly higher levels of overall character development and engaged more frequently than Black males in ethnic studies and cultural awareness workshops, as well as internship participation. Aside from character predisposition and community service, Black women reported higher levels on all of the college interaction and engagement variables, although some were nominal in difference statistically.One possible reason why women in this study outperformed men in regards to engagement might be how their personal values align with the institution. Liberal arts colleges tout themselves as environments that foster personal interactions and individualized attention. The women in this study might value this environment more than males and thus engage at higher levels. The women in this study might also feel as though they are treated more fairly than their male counterparts, which manifests in their willingness to participate in multiple activities. Moreover, women might be more motivated to engage in their collegiate experience at a higher level than men. These findings continue to support the need for faculty and staff to consider how and which type of engagement activities most benefit Black males. This might include the incorporation of living and learning communities and student organizations that specifically cater to the unique identities of these individuals. Additionally, more empirical research may be warranted on Black males’ overall experience. In summary, the relationship between students’ character development and certain college interactions and activities provides further evidence that engagement significantly contributes to students’ acquisition of both personal and educational goals. When an institution can provide opportunities that promote and facilitate exploration, engagement, and interaction with educationally purposeful endeavors, it demonstrates a culture that values the education of the whole person, that is, an educational synthesis of social, emotional, moral, and intellectual development. Institutions should continue to fortify their commitment to character development by enhancing existing and creating new opportunities for students to expose themselves to experiences that advance learning and development holistically. As observed in the present study, successful student engagement and character development as an outcome can be challenging. The significant variance that can exist between student engagement expectations and the quality of those interactions and activities may provide an imbalanced picture.

5. Limitations

- The institution utilized for the present study is a private baccalaureate liberal arts institution located in the Midwestern United States and serves a diverse and predominately residential student population. The applicability of the findings to other campus settings is unknown. The survey instrument employed was administered to undergraduates in their senior year. The significance of the findings may be best understood when comparing the results with published analyses of larger, survey data elements with more diverse populations that address similar questions.These limitations do not dilute this study’s contribution to the literature on the significant relationship between certain college interactions and character development. Specifically, the analyses provide information that supports the important role institutions play in shaping the character of their students. Moreover, the findings associated with Black students further elucidate the important role that engagement plays in the collegiate careers of students, and challenges institutions to continue to examine how they can better facilitate these processes. In sum, this study responds to the social and political environment in which higher education exists. The findings underscore the importance of how college affects students, which ultimately impacts larger social issues in this country and around the world. The present study provides additional insights into the role that institutional policies and practices around engagement resources influence the entire higher education landscape.

Appendix A. Content of Multiple Item Scales

- Student Information Form (SIF)Predisposition to Character1) Attended a religious service2) Becoming involved in programs to clean up the environment3) Developing a meaningful philosophy of life4) Future Activity: Socialized with someone of another racial/ethnic group5) Helping others who are in difficulty6) Helping to promote racial understanding7) Influencing social values8) Participating in a community action program9) Performed volunteer work10) Socialized with someone of another racial/ethnic group11) Understanding of othersCollege Senior Survey (CSS)Character1) Ability to work cooperatively with diverse people2) Becoming involved in programs to clean up the environment3) Developing a meaningful philosophy of life4) Helping others who are in difficulty5) Helping to promote racial understanding6) Influencing social values7) Integrating spirituality into my life8) Leadership ability9) Participating in a community action program10) Performed volunteer work11) Prayer/meditation12) Raising a family13) Tolerance of others with different beliefs14) Understanding of othersCollege Senior Survey (CSS) (continued)Student-Faculty Interaction1) Advice and guidance about your educational program2) An opportunity to apply classroom learning to "real-life" issues3) Emotional support and encouragement4) Feedback about your academic work (outside of grades)5) Help in achieving your professional goals6) Help to improve your study skills7) Honest feedback about your skills and abilities8) Intellectual challenge and stimulationDiverse Peer Interaction1) Dined or shared a meal2) Felt insulted or threatened because of your race/ethnicity3) Had guarded interactions4) Had intellectual discussions outside of class5) Had meaningful and honest discussions about racial/ethnic relations outside of class6) Had tense, somewhat hostile interactions7) Shared personal feelings and problems8) Socialized or partied9) Studied or prepared for class

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML