-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Education

p-ISSN: 2162-9463 e-ISSN: 2162-8467

2016; 6(4): 101-106

doi:10.5923/j.edu.20160604.03

The Effect of Lexical Chunks on Kurdish EFL Learners’ Writing Skill

Hassan Basil Abdul Qader

Department of English Language, University of Zakho, Kurdistan Region, Iraq

Correspondence to: Hassan Basil Abdul Qader, Department of English Language, University of Zakho, Kurdistan Region, Iraq.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2016 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

This paper aims at investigating experimentally the effect of using lexical chunks on the achievement of third-year-university students of English in the descriptive essay writing. To achieve this aim, the present study tries to provide an answer to the following question: does drawing students' attention to the lexical chunks commonly used in various situations help in better achievement in EFL descriptive essay writing classes as opposed to the currently used method of teaching? Also two null hypotheses are posed. The first tells that there will not be a statistically significant difference between the mean scores of the experimental group and those of the control group in the descriptive essay writing achievement pretest. While the second one is that there will not be a statistically significant difference between the mean scores of the experimental group and those of the control group in the descriptive essay writing achievement posttest. The two groups pre-test post-test experimental design was adopted. After three weeks of instruction, the findings show that there is a significant difference between the experimental group and the control group in the post-test in favor of the experimental group. Consequently, the major findings validated the first hypothesis of the study, but invalidated the second one.

Keywords: Lexical approach, Lexical chunks, and descriptive essay writing

Cite this paper: Hassan Basil Abdul Qader, The Effect of Lexical Chunks on Kurdish EFL Learners’ Writing Skill, Education, Vol. 6 No. 4, 2016, pp. 101-106. doi: 10.5923/j.edu.20160604.03.

Article Outline

1. The Statement of the Problem

- Recent trends in language teaching emphasize the centrality of lexis in language teaching as opposed to grammatical items and structures. They stemmed from the assumption made by Wilkins (1972) that "without grammar little can be conveyed but without lexis nothing can be conveyed". This view has been confirmed by recent trends in linguistic theory, language acquisition and classroom practice. Modern linguistic theory nowadays pays more attention to lexicon than to syntax. This, in fact, is the essence of the LA. Lewis (2002) sees language as essentially made up of chunks. He thinks that concentrating on single words denies the learners to see the essential patterns of the language. He adds that it is better to raise students' awareness of different kinds of chunks that fit different situations. Also, it is noted that Kurdish students, who are studying in the University of Zakho, Department of English, can manipulate some grammatical rules which enable them to write. However, when they come to write an essay, it is found that they produce such sentences which are, if grammatically correct, still odd or rarely used. For example, one of the students wrote: (We went to Arbil in order to "change whether"!). Although this sentence is grammatically correct, it is still odd and wrong. This mistake is due to selecting the wrong chunk, while the students can, instead, choose a chunk such as (in order to have fun). In fact, it is expected that the main reason behind this phenomenon is that the commonly used method (which focuses on form rather than meaning). Accordingly, the research question is crystalyzed in the following way: does drawing students' attention to lexical chunks that are commonly used in various situations of descriptive essays help in better achievement in essay writing classes as opposed to the currently used method of teaching?

2. Hypothesis

- For the sake of experimentation, the following two null hypotheses are posed. The Alpha level is set at 0.05:Ho1: There will not be a statistically significant difference between the mean scores of the experimental group and those of the control group in the descriptive essay writing achievement pretest.Ho2: There will not be a statistically significant difference between the mean scores of the experimental group and those of the control group in the descriptive essay writing achievement posttest.

3. Aim of the Study

- The aim of the present study is to verify the hypothesis already posed and to provide a research-based answer to the question already raised. This study adopts focusing on the lexical chunks to increase students' proficiency in essay writing in EFL classrooms at university level. It has been decided to concentrate on multi-word prefabricated chunks. These chunks occupy a crucial role in facilitating language production and being the key to fluency.

4. Literature Review

- The Lexical Approach (henceforth LA) is a method of teaching a foreign language developed by Michael Lewis in the 1990s. It is based on the assumption that an important part of language acquisition involves the ability to comprehend and produce lexical chunks as unanalyzed wholes, and these chunks have become the raw data by which learners perceive patterns of language traditionally thought of as grammar (Lewis, 2002). The LA to language teaching is based on the belief that the building blocks of language learning and communication are not grammar, functions, notions, or some other unit of planning and teaching but lexis, i.e. words and word combinations. The centrality of lexis means that teaching grammatical structures should play a less important role than it was in the past (Lewis, 2000, p.8). He (2002, p. 33) adds that more meaning is carried by lexis than grammatical structure. And focus on communication necessarily implies increased emphasis on lexis, and decreased emphasis on structure. Of all error types, learners consider vocabulary errors the most serious ones. This is because vocabulary errors lead to misunderstanding and breaking down of communication. Blass (1982, cited in Gass and Selinker, 2008, p.449) indicated that lexical errors outnumbered grammatical errors by 3:1 in one corpus. Moreover, native speakers find lexical errors to be more disruptive than grammatical errors. Grammatical errors generally resulted in structures that are understood, whereas lexical errors may interfere with communication. Consequently lexical chunks have a vital role in the teaching process.Many attempts have been made to define lexical chunks. Becker (1975) defines lexical chunks as a particular multiword phenomenon and presented in the form of formulaic fixed and semi-fixed chunks. Nattinger and DeCarrico (1992, p: 1) describe them as chunks of language of varying length and each chunk has a special discourse function. Other researchers see that the recurrence is another important feature of lexical chunks such as Biber, Jonsson, Leech, Conrad, and Finegan (1999, p: 990) who define them as "recurrent expressions regardless of their idiomaticity and regardless of their structural status". While wray (2000, p: 465) added a mental explanation to the definition saying that: a lexical chunk is a sequence of prefabricated words that are stored and retrieved as a whole from memory at the time of use. The definitions previously mentioned can thus be put in one definition: lexical chunks are a group of word combination that frequently occur in a language with special meaning and function.

4.1. Classification of Lexical Chunks

- Lexical chunks are classified in different ways for there is no fixed classification agreed upon by linguists. Each linguist has his own classification. The widely accepted classifications are those of Nattinger and DeCarrico (1992), and Lewis (1993).Nattinger and DeCarrico (1992, p: 45) divided lexical chunks into four types:(1) Poly-words: are fixed and short lexical phrases which are associated with different types of functions. For example: idioms (kick the bucket), topic shifters (by the way), summarizers (all in all).(2) Institutionalized expressions: are lexical phrases which have similar length as a sentence with little variability. They have particular social functions specially in conversation. For example: greeting (how are you?), accepting suggestion (I agree with that), inviting (would you mind …?), leaving (I have to go now).(3) Phrasal constraints: are short to medium length phrases. They include a variety of categories of lexical phrases and associated with various functions such as: farewell (see you later), timing (a … ago), connector (as well as), apologizing (I am sorry about …).(4) Sentence builders: refer to those phrases that allow for substitutions of their structure to express different ideas. For example: adding (not only … but also), comparator (the … er the …. er), suggesting (My point is that …), topic marker (let me start with/ by …).The other classification of lexical chunks is that of Lewis (1993, p: 92-95) in which he classifies them also into four types:(1) Poly-words: are rather fixed combination of words. The parts of a poly-word cannot be substituted with others without changing the meaning. For example, (on the other hand, by the way)(2) Collocations: are pairs of words that usually go together. We usually know a word by the word it keeps. For example: (knife and fork, bread and butter). However, the relationship between words within a collocation has sometimes more flexibility than those within a poly-word. For instance, (prices) can collocate not only with (fell) but also with (rose).(3) Institutionalized expressions: help to manage aspects of oral interaction with certain pragmatic functions. For example: (just a moment please), (can I give you a hand?).(4) Sentence frames: This sort of chunks is usually used in writing. This is the only difference between sentence frames and institutionalized expressions which are only used in oral interaction. (one of the most important … is that …), (my opinion is that …).The classification of Nattinger and DeCarrico (1992) and Lewis (1993) are complementary. Hence a combination of the two classifications is made and some types of chunks have been deleted since they have no direct relationship with the present study which is concerned with writing. Accordingly, the new classification consists of the following:(1) Poly-words: include discourse markers, preposition phrases, idioms, and any frequent essential vocabulary for learners to acquire.(2) Collocations: refer to pairs of words that frequently co-occur with each other. For example, noun + noun (day and night), verb + noun (shake hands), adjective + noun (splendid future).(3) Sentence heads or frames: usually structure the essay. For example, (That is not as ... as you think; The fact is that/ The suggestion/ problem/ danger was ... ; In this paper we explore... ; Firstly... ; secondly... ; Finally ...).

4.2. The Teaching of Lexical Chunks

- The LA emphasizes the teaching of lexical chunks. These chunks have a significant role in developing L2 writing proficiency (Cowie and Howarth, 1996). Granger (1998, p. 151) found out that lower and intermediate learners catch and use fewer lexical chunks than native speakers. A good explanation for native speakers fluency is that they use much of the same language over and over rather than structuring new sentences each time they write (Pawley and Syder, 1983, p. 208). In other words, they keep on using frequently used lexical chunks.For this reason, the teachers can follow four main stages in essay writing classes. The first stage is to help their students identify, organize and use lexical chunks appropriately. The students must also be presented with activities that raise their consciousness that any language in the world cosists basically of raidy-made chunks. The second stage can start with text analysis. The students are presented with essay samples to read. Then they are asked to identify the different types of lexical chunks. In the third stage, the students are asked to write an essay using similar chunks. In the fourth stage, the students’ performance is marked and evaluated.

4.3. Previous Work

- Many attempts have been done by researchers concerning the relationship between lexical chunks and EFL learners proficiency. What is meant by EFL (English as a Foreign Language) is a traditional term for the use or study of the English language by non-native speakers in countries where English is generally not a local medium of communication (Crystal, 2003, p. 256). Starting with Erman and Warren (2000) who investigated written discourse finding that lexical chunks constitute 52.3%. In another study, Granger (1998, p. 151) mentions that “learners use fewer lexical chunks than than their native speaker counterparts”. Haswell (1991) stated that: in order to be a successful academic writer, an L2 learner is required to master the use of lexical chunks. On the contrary, the absence of such lexical chunks is a characteristic of novice writers. Many other linguists have conducted experiments on the effect of lexical chunks on writing proficiency. For example, Nattinger and Decarrico (1992) did an experiment to examine the ways that lexical chunks are organized in written discourse. They concluded that the input of these lexical chunks can help EFL learners to express themselves well in the writing. . In another study, Ilyas and Salih (2011) investigated experimentally the effect of lexical chunks on the achievement of second-year-university students of English in composition writing. They found that the lexical chunks were beneficial to the second-year students. Finally, Snellings, Van Gelderen, and de Glopper (2004) found out that lexical chunks have a positive effect in improving narrative L2 writing.After all, all of these studies indicate, in a way or in another, to the importance of adopting the lexical chunks in developing writing skill. And that the mastery of these chunks is crucial to create successful academic writers. To date, to the researcher's knowledge, no study has investigated the impact of lexical chunks on developing EFL learners skill in descriptive essay writing.

5. Methodology

- The aim of this chapter is to report an experiment and to give a comprehensive description of the whole procedures which have been adopted to achieve the aim of the research and verify its hypotheses. These procedures include: design, participants, pretest, posttest, procedure, and statistical tools used for analyzing and interpreting the collected data.

5.1. Design

- The study was conducted following an experimental design which involved control and experimental group, a pretest and posttest, and a treatment with the experimental group. Each group was taught the same materials with different methods of teaching. The participants of the experimental group received six sessions of treatment.

5.2. Participants

- The participants of the study consisted of (40) third year students at the Department of English, Faculty of humanities, University of Zakho for the of the academic year 2015- 2016, (20) in the experimental group and (20) in the control group. As for gender, the two groups were found to be a mixture of both genders. The EG consisted of (9) males and (11) females, whereas the control group included (8) males and (12) females. Their age ranged from (20) to (22).

5.3. Instrumentation

- At the beginning of the study, a pretest was conducted in order to know the participants’ initial knowledge and select the participants who are at equivalent level. The students were asked to write an essay describing a place. They should write at least 250 words. The pretest was carried out in class under the supervision of the teacher in order to make sure that the students do it by themselves. After the test, all the essays were collected and graded by two specialized scorers who followed the same criteria The researcher has adopted the Jacobs et al. (1981) rubric, which is the most widely used and agreed upon rubric for scoring non-native essay writing. This rubric contains five components: (1) content, (2) organization, (3) vocabulary, (4) language use and (5) mechanics. Each component has a four level score corresponding to four sets of criteria. The total score is out of (100). The average scores between the two scorers were the ultimate scores. After that, their scores were collected and analyzed.At the end of the experiment, a posttest was conducted in order to investigate the progress made specially in the EG after being exposed to the treatment. In the posttest, the students were also asked to write an essay on the same topic they have already written about in the pretest. This also happened under the supervision of the teacher. After the test, all the essays were collected and graded by the two scorers according to the same criteria. The average scores between the two scorers were adopted. After that, the scores of the two classes were collected and analyzed and then the two results were compared to each other in order to find whether there was any significant improvement of the students’ writing skills after conducting the experiment.

5.4. The Application of the Experiment

- Before applying the experiment, the researcher made a number of meetings with the instructor who was going to implement the experimental lesson series in order to acquaint her with the aim of the study and the procedure to be followed when teaching the experimental group. The experiment lasted three weeks. Both groups had the same material which was selected descriptive essays from the net. For example, (The Weekend Market, Your Favorite Restaurant, Your neighbourhood, etc). The only difference is that the plan for teaching writing to the EG was set according the methodology of the LA which means focusing on lexical chunks. While the plan for teaching writing to the CG was set according to the currently used method.Four steps were followed with the EG:The first step: the teacher explains to the students what is meant by lexical chunks, the importance of these chunks in writing, and how many types of chunks are there. The teacher also raises students’ awareness that any language in the world, including English, consists mainly of chunks.The second step: at the beginning of every writing lesson, the students were presented with essay samples. They were asked to elicit the chunks they meet and to give the type that these chunks belong to. This can help the students to retain the chunks in order to use them later in writing. For example, (in the middle of, in front of) are prepositional phrases which are classified as polywords.The third step: after analyzing the essays, the students were asked to write a descriptive essay about a specific topic. It was the time to use the chunks they had memorized and learnt before. Before starting to write, the teacher also used to list down on the board some useful chunks (such some sentence frames) in order to ease the process of writing. For instance, (One of the most beautiful places in kurdistan is -------- ; Wherever you go, you won't find a paradise on earth like -------- ; First of all; Secondly; Thirdly, etc).The fourth step: The students’ essays were marked and evaluated. As mentioned earlier, the Jacobs et al. (1981) rubric was followed for scoring the students' essays. This rubric contains five components: content, organization, vocabulary, language use and mechanics. Each component has a four level score corresponding to four sets of criteria. The teacher usually commented on the essays and selected the best ones and utilized them as models to be imitated by other students. After conducting these four steps, the students’ writing performance were expected to be improved.

6. Results

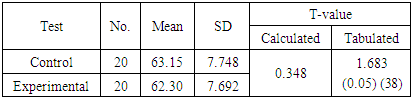

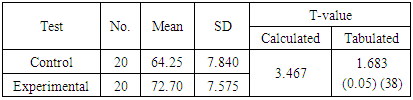

- In order to trace the effect of lexical chunks in comparison with the currently used method in teaching descriptive essay writing on the subjects' achievement, the overall scores obtained by the subjects of the CG and EG in the writing tests were computed and contrasted using a statistical analysis system (SPSS 22). An unpaired t-test was applied to see whether the difference was statistically significant or not. Below are the results and discussion of the findings obtained.As for the first hypothesis, the raw scores of the pre-test were statistically computed using the t-test for the two independent samples. The mean scores, standard deviation and the T calculated are shown in Table 1.

|

|

7. Discussion of the Results

- The results clearly indicate that raising students’ awareness of lexical chunks was more effective than the commonly used method. This means that the lexical chunks play a positive role in improving the college students’ English essay writing. The students in the experimental group are able to produce the language and comply with the writing tasks. The results also indicate that this experiment turns to demonstrate significantly more learning effects for teaching the words and word combinations and training the learners to acquire this skill. Besides, committing less grammatical mistakes was another fruit of adopting lexical chunks. Also these results show that the control subjects’ failure in the final test is due to the fact that they are neither able to recognize nor to produce these chunks or to use them in a particular context. Thus, the answer to the research question (Does drawing students' attention to lexical chunks that are commonly used in descriptive essays help in better achievement in the writing classes as opposed to the currently used method of teaching writing?) which is already addressed is yes; Lexical chunks have a positive effect for teaching writing at college level and did help in developing the learners' writing skill.

8. Conclusions

- This study reveals the importance of teaching lexical chunks in improving students essay writing. The learners need large repertoire of lexical chunks that fit different situations in the process of writing rather than grammatical rules. More meaning is carried by lexis than grammatical structure. Thus, in the light of the findings of the current research, it can be concluded that teaching writing through lexical chunks proves to be more useful for the EFL students than through the currently used method and it has a positive effect not only on appropriacy, but on fluency and grammar. It can also be concluded that Iraqi learners of EFL at college level are certainly in need of a large repertoire of lexical chunks that can improve their communicative ability even if they generally know how to manipulate grammatically correct sentences in a given situation, the way they use to reach the goals is often inappropriate and might lead to breakdowns of communication.

9. Recommendations

- In the light of the remarkable improvement in the students' achievement in the writing, instructors of writing are recommended to: a) Integrate lexical chunks instruction into writing activities.b) raise their students’ awareness of these chunks.c) Present essay samples to be analyzed.d) Ask learners to keep a lexical notebook in order to write down. chunks in it and be able to memorize them whenever needed.e) Ask students to use dictionary as a learning resource rather than reference work.f) Reinforce and recycle chunks as much as possible.g) Encourage learners to listen to native speaker, such as listening to the radio, watch TV, read books or magazines... etc, and to try to write down chunks they meet in their lexical notebooks.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML