-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Education

p-ISSN: 2162-9463 e-ISSN: 2162-8467

2016; 6(2): 40-47

doi:10.5923/j.edu.20160602.03

Right to Education: An Analysis of the Role of Private and Public Schools in Upholding Educational Rights of Marginalized Group

Rabiya Bazaz

Department of Sociology, Aligarh Muslim University, Aligarh, Uttar Pradesh, India

Correspondence to: Rabiya Bazaz , Department of Sociology, Aligarh Muslim University, Aligarh, Uttar Pradesh, India.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2016 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Education is essential for individual empowerment and societal development. Education, being an important development indicator is recognized as one of the fundamental rights of an individual. However, increasing inequality in educational system has resulted in the violation of right to education of most of the marginalized groups. This article attempts to analyze the role of private and public schools in providing basic education to marginalized groups. It introspect the participation of marginalized groups in elementary education and role of government in enhancing their participation. It questions the fragmented approach adopted by the government to bring marginalized section of society in ambit of elementary education.

Keywords: Elementary Education, Right to Education, School, Marginalized groups, Privatization

Cite this paper: Rabiya Bazaz , Right to Education: An Analysis of the Role of Private and Public Schools in Upholding Educational Rights of Marginalized Group, Education, Vol. 6 No. 2, 2016, pp. 40-47. doi: 10.5923/j.edu.20160602.03.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- An effective education system can bring a number of benefits to the society. The contribution of education very much depends on the type and quality of education which society imparts. Education system can pave way for social and sustainable development only when everybody gets fair and just opportunities to cherish their right to education.Historically Indian education system has been elitist. It served as a gatekeeper permitting avenue to those who were placed higher in the social hierarchy and excluded those who were placed at the bottom of hierarchy. This trend continued even after independence, whereby those who remained excluded from education for social, economic and geographical reasons could not become major concerns of policy makers. The historical barrier coupled with post-independence development, regarding access to education has given rise to many challenges to the goal of universalization of elementary education in India.Disproportional educational opportunities and lack of precedence towards basic education gave rise to the hierarchy of schools and created a division of private and public schools. This division creates social injustice in society by increasing the disparity in educational opportunities along socio-economic lines which resulted in violation of right to education of most of the marginalized groups.Here marginalized groups refer to those that have been deprived of basic education as evident from their performance on basic education indicators. The list corresponds closely to the commonly acknowledged socially and economically marginalized categories of Schedule Castes, Schedule Tribes, minorities, girls and poor [1]. According to the census 2011, total composition of Schedule Caste and Schedule Tribe population is 16.6 per cent and 8.6 per cent respectively and for female and minority it is 48.9 percent and 19.5 percent respectively. Today India has largest number of illiterate people in the world where the incidence of illiteracy is high among SC, ST, women, and minority which form a large portion of India’s population [2].

2. Objectives & Methodology

2.1. Objectives

- This paper is intended to analyze following three objectives:Ÿ Role of government policies in fulfilling the right to education of marginalized groups.Ÿ Impact of private schools on the right to education of the marginalized groups.Ÿ To suggest measures for inclusion of marginalized groups in private as well as in public schools.

2.2. Methodology

- This paper has used analytical and comparative methods. Information is collected from related literature and secondary data. Empirical studies and government reports have also been used for collecting information.

3. Conceptual Framework and Background

3.1. Education and Development

- Education is an integral component of development. Development is about enhancing human choices or providing a range of opportunities in order to live productive and creative lives and thereby to develop the human capability. Education is regarded as essential in enhancing human capability [3]. Through education, we are able to be more productive and therefore contribute to economic development. Education enhances our choice and freedom, develops awareness and broadens our horizon and thereby contributing to self-development. Thus, education not only plays a role in human capital but also in enhancing human capability [4]. Education is an important indicator of development which influences other development indicators like health, nutrition, income, employment etc [5]. An efficient educational system develops necessary skill and knowledge while infusing a sense of confidence and awareness among masses. It enables them to earn their livelihoods and help them in coming out of poverty and move into prosperity.Emile Durkheim views education as an important social institution which plays a pivotal function in society like skill development, socialization, creation of new knowledge and technologies in society [6]. However, Marxists and neo-Marxists view formal education as an important mechanism for the reinforcement and perpetuation of societal stratification system. Indeed, the type and quality of education provided in a society determines the benefits of education. Education is a public good which is always beneficial for society and paves way for true development. To ripe the benefits of education, it is essential that, in a particular society, education system must fulfill two important conditions: one is to provide equal access to formal education and second once enrolled in educational system all individual must be provided same opportunity for success [7].

3.2. Elementary Education

- Elementary education is the backbone of entire educational system. It lays the foundation for all levels of learning and development. There is considerable global as well as Indian research that has established without doubt that investing in early years of learning is very important [8]. However in case of India, critics have claimed that it has overly focused on higher education at the expense of school education and this has contributed to its uneven development, whereby the poor are largely marginalized from educational process in particular and development process in general [9].

3.3. Educational System in India

- India, with more than a billion residents, has the third largest education system in world. Education in India is provided by public as well as by private sector. A reading of Indian educational history reveals that it was notorious for its lack of social inclusiveness. Traditional Hindu education was tailored to the needs of Brahmin boys who were taught to read and write by a Brahmin teacher. Thomas Babington Macaulay introduced English education in India through his famous minute of February 1835 which advocated replacement of Indian forms of education with English education based on the idea that English education is a superior form of education. In this way, British introduced modern education into the Indian-subcontinent. However, under British rule, India’s educational system somehow continues to reflect the pre-existing elitist tendencies. Colonial rule contributed to a legacy of an education system, geared to preserving the position of more privileged classes. Being largely confined to Brahmins and higher classes, this system of education also excluded the masses [2]. For curbing traditional inequality in educational system, demand for a law on Free and Compulsory Education was made by Dadabhai Naoroji and Jyothiba Phule before the Education Commission (Hunter Commission) appointed in 1882. They demanded State-sponsored free education for all children for at least four years. This demand was indirectly acknowledged in the Commission’s recommendations on primary education. However due to various socio-political reasons, these efforts for universalisation of elementary education could not yield desired results [10].

3.4. Right to Education

- After independence, a number of steps were taken to bring equality in educational system. The preamble of the constitution of India lays down basic and immutable structure of Indian constitution affirming the objective of securing for all citizens of India basic rights of dignity, freedom and equality especially equality of opportunity and status. Article 45 of Indian constitution, which comes under the Directive Principles of State Policy, mandated the State to endeavour to provide free and compulsory education to all children up to the age of fourteen years. Article 39 lays out the role of State policy in fostering opportunities for social justice and welfare. Article 29 and 30 of the fundamental rights, talks about protection of educational and cultural rights of minorities and allow minorities to establish and administer their educational institutions. But the most dynamic step taken for universalization of elementary education came with 86th amendment to the constitution which added article 21-A in the constitution. Article 21-A says that education is a fundamental right essential for well-being of the people and makes it mandatory for state to provide free and compulsory education to all children in the age group of six to fourteen years [11]. Following from this the Right to Education Act was drafted and passed on 27 August 2009.Right to Education Act (RTE Act) describes modalities of free and compulsory education under article 21A and specifies minimum norms in elementary schools (both in private and public schools). RTE Act is the giant step in the educational field [12]. “It entitles all children between the ages of 6-14 years free and compulsory admission, attendance and completion of elementary education. It provides for children’s right to an education of equitable quality, based on principles of equity and non-discrimination” [13]. For the first time, this act laid down minimum quality parameters which schools (both private and public schools) have to fulfill. Thus, the basic requirements of the infrastructure, teacher qualification and curriculum design, teacher-pupil ratio and classroom transaction have been enunciated in the act. Section 12(1) (c) of RTE Act require all private schools to reserve 25 percent of their seats for socially and economically disadvantageous groups, on the basis of reimbursement which government will provide to private schools for such admission. There is also provision for special training to school drop outs to bring them at par with students of same age. It prohibits physical punishment and mental harassment, screening procedures for admission of children, capitation fee and running of schools without recognition [13]. Despite the strong principles of social justice and welfare included in the constitution to bring education to those who were denied even basic access to education for generations, for social, economic or geographic reasons, exclusion appears not to have been at the forefront of policymaking for decades after independence. This long period of neglect of basic education for marginalized sections has resulted in their exclusion from education in particular and from development process in general.Lack of resources and high demand for education pushed India toward privatization which further entrenched existing inequality and gave rise to new forms of exclusion [1]. According to International Human Right Law, private education refers to education that is provided by non-state actors [14]. Privatization of education has garnered international debate where some people support it and some vehemently oppose it. Private education has been promoted on many grounds like private schools have been consistently yielding excellent results and it has enhanced the quality of education and has increased access to education [15]. However, it is argued that benefits of private schools remain confined to few people. It has been argued that privatization of education has created social injustice in society by increasing disparity in educational opportunities along socio-economic lines which resulted in the violation of the Right to Education of most of marginalized groups [14]. This privatizing approach goes against the socio-economic objectives of the directive principles of Indian constitution. If private schools have created injustice, then there is a need to probe to what extent public school have created justice in providing free and qualitative education within the framework of universalization especially keeping in mind special needs of marginalized.

4. Finding and Discussion

4.1. Elementary Education of the Marginalized Section

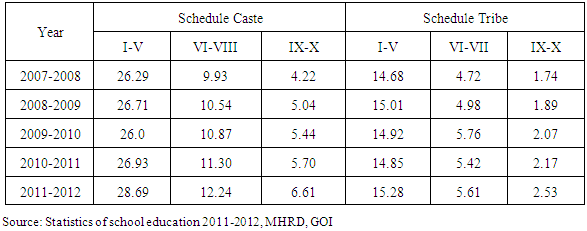

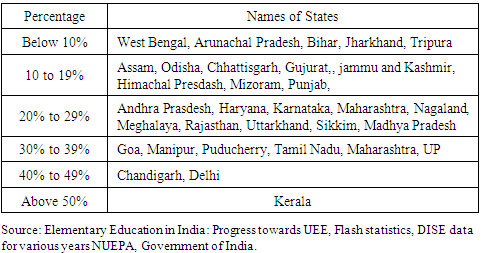

- Long period of neglect of elementary education has sown the seeds for huge backlog in the universalization of elementary education for marginalized sections. Although there is a slight increase in overall enrollment pattern of marginalized groups (Table-1) but the type and quality of education which they get causes specific deprivations among them.

|

|

|

4.2. Government Policies and Elementary Education

- The first National Policy on Education (NPE) was formulated in 1968 – almost two decades after the framing of Constitution. This report talks about providing equal educational opportunity to all. However, it does not specify proper financial and administrative plan for achieving this objective. These loopholes of National Policy on Education (1968) are also mentioned in the review carried out by next National Policy on Education (1986). “National Policy on Education (1968) did not get translated into a detailed strategy of implementation, accompanied by the assignment of specific responsibilities and financial and organizational support. As a result, problems of access, quality, quantity, utility and financial outlay, accumulated over the years, have now assumed such massive proportions that they must be tackled with utmost urgency” [17]. National Policy on Education (NPE) of 1986, which was revised in 1992, recognizes the need of basic education for those who were left behind. However, one of its drawbacks was that it does not take into consideration needs and demands of poor and marginalized. Unfortunately, increase in physical access was done at a huge cost to quality, underlying the elitist tendency in policy thinking, which sanctioned substandard educational facilities for poor and marginalized [1].Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan (SSA) forms the cornerstone of government interventions in basic education for all children. Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan (SSA), launched in November 2000 as an umbrella programme, aims at supporting and building primary and elementary education projects. Its primary goals are: to provide quality education, to universalize elementary education, and to reduce social, regional and gender gaps [13]. However, Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan (SSA) could not achieve much of its desired goals. Several studies reveal that Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan (SSA) is characterized by implementation flaws and financial constraints [1, 18, 19]. There exist two mechanisms for delivering basic education under SSA, one works at central level which is responsible for maintaining permanent education cadres (including the teachers), conducting inspections, some teacher training, mid-day meals, data collection, disbursements (salaries, incentives, pensions) and another works at state level which is responsible for implementation of the scheme and academic inputs. This bifurcation has led to confusion in terms of responsibilities and accountabilities [1]. Fund allocation is another problem within SSA which comes with extremely strict and inflexible financial norms determined centrally. Funds are often not received at appropriate time by the schools which make it difficult for them to make best use of funds. Also, fund utilization remains problem under SSA. A close look at the state level scenario reveals that several states are unable to utilize funds adequately, the major ones being Bihar, Jharkhand, Madhya Pradesh, Odisha, Punjab, Uttarakhand and West Bengal [18].Rao (2009) in his study “Structural Constraints in Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan Schools” says that despite adopting a number of employment reservation policies for marginalized groups, posts reserved for them often remain vacant mainly because of the absence of eligible candidates. SSA, despite its emphasis on decentralisation and in-built flexibilities, was not making much headway in a socially and economically differentiated context. The problem was not only of implementation but rather reflected a perception of poor quality on the one hand and a lack of understanding of social relations and structural constraints on the other hand. A comparison of several schools reveals that schools located near the areas of marginalized groups are not provided with adequate learning facilities which later results in their drop out. It points to the setting up of differential standards and norms for different types of schools which consequently enhance inequalities even within the state education system in a single locality [20].

4.3. Right to Education and Elementary Education

- India took almost six decades to make education a fundamental right. Following from this the Right to Education (RTE) Act was drafted and passed on 27 august 2009. Right to Education (RTE) Act also faces some challenges and the biggest among them is that those involved in the implementation of RTE Act have not fully grasped the fact that children who still do not have access to schools or who are being forced to drop out or those who are not learning adequately are witnessing violation of their fundamental rights.

4.4. Privatization of Education and Elementary Education of the Marginalized

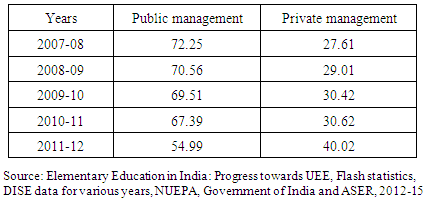

- India’s level of spending on education in comparison with other developed and a developing country is very low. India even does not spend 4 percent of GDP fully on education [21]. Increasing demands for education and low spending on education (which results in poor performance of government schools) give rise to mushrooming growth of private schools [8, 22]. The number of private schools is considerably increasing in India and there is corresponding decline in the proportion of government schools, which are main source of providing education to disadvantageous groups [23]. Annual status of education report (ASER) recognize that number of children enrolled in primary private schools in 2014 would be about 41 per cent Further, by 2019 private schools will play major role in imparting elementary education and public school system will be relegated to secondary status in imparting elementary education (Annual status of education report [24]. (Table-4)

|

|

4.5. Hierarchy of Access and Inequality of Opportunity

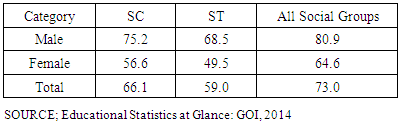

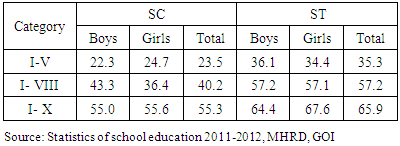

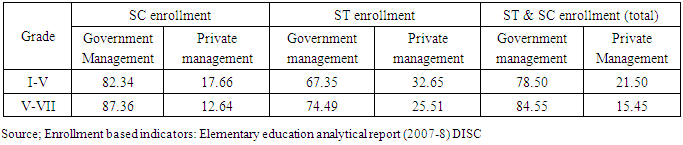

- Studies reveal that lopsided policies and lack of priority given to basic education, especially for poor, gave a huge boost to private school industry. Two track education systems have appeared where local government schools are deemed for poor and private schools are attended by better-off social groups creating a hierarchy of schools [1, 8, 15]. Data shows that children of marginalized groups like SC, ST are overwhelmingly enrolled in public schools and numbers of these children enrolled in private schools are negligible. (Table- 6)

|

4.6. Quality Education and Marginalized Group

- One of the major goals of Right to Education Act 2009 is to provide elementary education of equitable quality to every child between the age group of six to fourteen years. It lays down the basic parameters of quality education like good infrastructure, availability of learning material, proper assessment and monitoring, teacher training and qualified teachers [26]. In several studies, educational quality was explored through household survey and interview with parents, where parents frequently cited their belief that private education is of better quality than public schools [8, 15, 21, 23, 25]. Students in private schools have better learning outcome than students in public schools [27]. The study reveals that parents believe that even low-cost private schools comparatively provide better quality education than public schools [25]. However, it is rich and middle class who dominate enrollments in private schools and later acquire dominant position in society. According to Marxian theory, formal education in capitalist societies tends to solidify the domination of propertied and powerful ruling class over the non-propertied and powerless lower class [7]. Not all communities are equally benefited by privatization of education. This privatizing approach goes against the article 39(b)-(c) of the Directive Principles of the Indian constitution which talks about equal distribution and prevent concentration of wealth in the hands of few. Privatization of education is not availing many benefits to poor and marginalized sections, which are overwhelmingly enrolled in public schools. Thus, quality schools are not accessible to all [8].Right to Education (RTE) Act not only talks about free and compulsory education but it also proposes quality education. According to RTE rules, there should be at least one qualified and trained teacher for every 30 pupils [13]. However, government fails to maintain the pupil-teachers ratio of 30:1 [18]. Section 23(2) of the Act provides a time frame of five years to ensure that all the teachers in elementary schools are professionally trained. Despite this, school teachers do not have required minimum qualification to ensure children’s right to quality learning. States like Bihar, Uttar Pradesh, West Bengal, Jharkhand, Chhattisgarh, Andhra Pradesh, Odisha, Madhya Pradesh and Assam report a large proportion of untrained teachers [18].Right to education is a right to quality education but poor people remain devoid of quality education [14]. These poor families, who feel dissatisfied with public schools, find themselves trapped in low-quality education with no real choice than to drop out. Poor quality of education stands as an obstacle for them to take part in the mainstream social and economic development process. Quality education is essential for the development of human capital. These socially and economically marginalized groups remain at the fringes of quality education which result in there drop out and high incidence of illiteracy. This reduces their chance to get ahead and thus remain trapped in inequality and unemployment.

4.7. Cost and Elementary Education

- The 86th amendment to the constitution declares education as one of the fundamental rights where every child between the age group of six to fourteen years is entitled to get free and compulsory education. Despite this, there is still direct or indirect cost of schooling which hinders children, especially from the lower section to attend school. Chandrasekhar Mukhopadhyay (2006) in his study, “Primary Education as a Fundamental Right Cost Implication” reveals that cost of schooling adversely affects the probability of children going to school, especially those who hail from a poor household. A World Bank survey of user fees in primary education across 79 countries revealed that India is one among thirteen countries which charge illegal fees. This reveals that there are direct or indirect costs which are incurred from the pupil in the form of fees, books stationery, which deter children from going to school. It is essential that government should come forward and should bear this expenditure so that children, especially from poor sections can attend school without any hindrance [28].

5. Suggestions

5.1. Upgrading RTE Act

- No doubt, educational policies in India have travelled some distance in removing inequality in the educational system by increasing physical access to most of the socially and economically marginalized groups. However, these policies have not given adequate attention to other important dimensions of basic education which reveal implementation and design loopholes of these policies and programmes. In principle, the Right to Education Act 2009, with appropriate modifications and financial provisioning offers a great opportunity to correct the anomaly of poor education outcomes and can deliver on long-standing commitment to providing basic and quality education to all especially to poor and marginalized. Unfortunately, short-term political gains and poor judgment on part of politicians and policymakers may continue to be major roadblocks in accomplishing this critical goal [18, 19]. Mehendale, Mukhpadhyaya and Namala in their study “Right to Education and Inclusion in Private Unaided Schools: An Exploratory Study in Bengaluru and Delhi” says that education department should be strengthened with the provision of a dedicated RTE cell. In some states like Kerala some initiatives have been taken in this direction. Such cell should work in close co-ordination with the relevant department of state government to define some of the unclear questions of the provision. The cell should be able to bring incoherence and convergence to the three functions of the government under RTE: regulation and monitoring, funding, awareness.

5.2. Focus on Public Schools

- Privatization of education is not the panacea for universalization of elementary education; if not regulated properly, it will only perpetuate inequality along socio-economic lines. Delivering education as a fundamental right is the primary goal of public education where access to education is not limited by any means whereas profit often remains main motive behind private schools where access to education is often limited [8, 22]. Keeping this thing in mind, there is a need for more public schools, which can provide free education to all. It should be remembered that the right to education is not only confined to free education but the right to education means quality education [14]. Thus, there is a need to invest more on improving the quality of public education so that quality schools should be accessible to all especially to the marginalized groups. Without a significant commitment by the state to improve the quality and reach of the government schools, dual track education system will continue to persist whereby marginalized group will be able to access the lowest quality of education and will remain away from education in particular, and from the development process in general.

5.3. Focus on Private Schools and Nonprofit Private Players

- It is essential that state should come out from neo-liberal approach. The government should ensure that private schools are working within the fold of RTE norms and are following its various provisions. It is essential to ensure admission of marginalized sections in private schools, under section 21 (1) (c) of RTE Act, in order to address widespread disparity in education institutions and to increase diversity in the private classroom. There are several non-profit private organizations like NGO’s (Pratham, Bodh Shiksha Samiti), international foundations (children investment fund foundation) faith-based trust schools (madrasas) which are engaged in education in a meaningful way. These non-profit private players are catering the educational need of disadvantageous groups. It is important that government should recognize their efforts and should promote their growth. Jagannathan (2000) in his study “Role of Non-Governmental organization in Primary Education” suggested partnerships between Government and non-Government sectors, especially between non-profit private players to close the gap in access, equity, and quality in elementary education [29].

6. Conclusions

- While concluding it can be said that development returns of education depend on certain important things like universalization of elementary education, skill based education, quality education, equal access to formal education and equality of opportunity for success. Today our education system is characterized by widespread inequality and exclusion. Marginalized groups often find themselves excluded from the system because the type and quality of education which they get are not availing many benefits to them. Increasing rate of drop out and illiteracy among marginalized groups keeps them away from the development process which will further intensify their problems of inequality, unemployment, and poverty. There is need of policy interventions where by government has to come up with appropriate educational policies and programmes and has to ensure their working. There is dire need of quality schools which should be accessible to all. If the government will abdicate this space, it is marginalized groups who will bear the brunt of this neglect. At this junction where the government is in the process to formulate new education policy, it is important to have a look on these education issues in order to take country toward the path of social and sustainable development.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML