-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Education

p-ISSN: 2162-9463 e-ISSN: 2162-8467

2016; 6(1): 13-16

doi:10.5923/j.edu.20160601.03

Medical Interns’ Learning and Mistreatment Received during the Internship Year. Are They Satisfied?

Alshomrani Yasser1, Althaqafi Mutaz2, Albarakati Baraa3

1Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, College of Medicine, Umm Alqura University, Makkah, Saudi Arabia

2Department of Obstetric and Gynecology, College of Medicine, Umm Alqura University, Makkah, Saudi Arabia

3College of Medicine, Umm Alqura University, Makkah, Saudi Arabia

Correspondence to: Alshomrani Yasser, Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, College of Medicine, Umm Alqura University, Makkah, Saudi Arabia.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2016 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

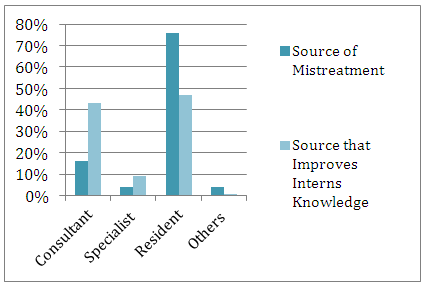

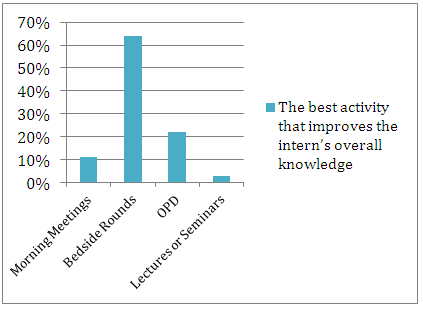

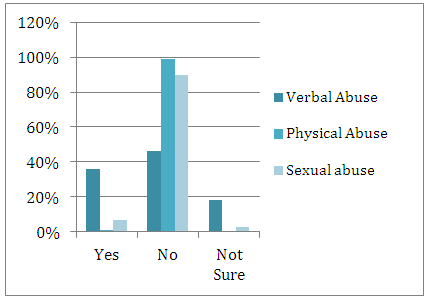

INTRODUCTION: The internship year is considered to be a golden period for doctors’ training, as they are exposed during that time to a majority of medical specialties and will gain more knowledge and clinical skills. In this research, we tried to find out the degree of satisfaction of medical interns in regards to the quality of education received either theoretically or clinically. We also explored the degree and different types of mistreatment and abuse the doctors faced during their training and whether or not they have reported it. METHODS: This is a cross-sectional study based on a questionnaire that was distributed online. The study was conducted among medical interns of the year 2013-2014 at the College of Medicine, Umm Alqura University, Makkah, Saudi Arabia. The total sample size was 127 medical interns. RESULTS: Up to 77% of our study population have an intermediate level of satisfaction about what they have learned during their internship year. Almost one half of the study population 46.7% agreed that the “residents” were considered to be the best at improving their knowledge, while 42.5% answered that the “consultants” were. Regarding the best activity that improves the interns’ overall knowledge, “bedside rounds” was the answer given by the majority of the interns 64.3%. Around 35.5% had personal experiences with verbal abuse, less than 1% experienced physical abuse, and 7.3% were victims of sexual abuse. CONCLUSION: Medical interns were moderately satisfied with what they had learned during their internship year. It is possible to improve their satisfaction if we decrease the different kinds of abuse that occur to them and if we improve some hospital activities like morning meetings and seminars. We need more studies to confirm whether or not all these recommendations are effective.

Keywords: Medical interns, Satisfaction, Learning, Mistreatment, Internship Year

Cite this paper: Alshomrani Yasser, Althaqafi Mutaz, Albarakati Baraa, Medical Interns’ Learning and Mistreatment Received during the Internship Year. Are They Satisfied?, Education, Vol. 6 No. 1, 2016, pp. 13-16. doi: 10.5923/j.edu.20160601.03.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Training in a medical field in general is considered to be one of the most difficult and stressful experiences for doctors and all other health care providers [1]. During different years of medical school and even residency years, the interns in their internship year experience more pressure and stress than they do in the rest of their working years [2]. The internship year is one mandatory year after finishing the undergraduate study in the college of medicine, which include rotations in medicine, general surgery, pediatric and obstetric and gynecology, in addition to two elective rotations. It is considered to be a golden year, as junior doctors are exposed to many medical specialties with different kinds of learning methods and different senior doctors. Usually, the interns will learn from their senior colleagues, but the question is how good they are in their teaching roles and how much the interns will properly learn [3]. It is apparent from previous studies that students, interns and junior doctors show better confidence and gain more knowledge and clinical skills when they get supervision from senior doctors [4].On the other hand, abuse and mistreatment is occurring in many aspects of life. Health care providers in medical fields, especially junior doctors, have the same experiences with mistreatment. It was reported in several studies that junior doctors are exposed to some kinds of mistreatment, including verbal abuse, physical abuse, increased workload and even sexual harassment [2, 5-9]. The objectives of our study are to gain more understanding about how satisfied medical interns are with the quality of teaching they receive, either theoretical teaching or clinical skills and to explore the degree and type of mistreatment they receive, how much it affects their outcomes and whether or not it has been reported.

2. Methods and Materials

2.1. Study Design and Setting

- This is a cross-sectional study based on a questionnaire that was distributed online from 1 to 31 July 2014 for medical interns of the College of Medicine at Umm Alqura University, Makkah, Saudi Arabia. Makkah city is the capital of Makkah province in Saudi Arabia.

2.2. Participants

- Medical interns of the College of Medicine at Umm Alqura University for the year 2013-2014 are the target population of our study. The objectives of the study were explained to them; then they agreed to the consent page, which is a requirement to be able to fill out the questionnaire. To be eligible for this study, participants should finish at least 10 months out of the total 12 months of their internship year. Any participant who doesn’t fulfill these criteria will be excluded from the study.

2.3. Measures and Outcomes

- Our questionnaire consists of many multiple-choice questions. For the purpose of assessing how much medical interns are satisfied with their knowledge, we asked them to answer on a scale from 1 to 5 (1=not satisfied and 5=completely satisfied). There was also another related question that we will discuss below.

2.4. Sample Size

- Using the sample size calculator of The Survey System software with a margin of error of 5% and a confidence level of 95% for a total population of 278 medical interns, including both male and female genders, the estimated sample size was 162 medical interns. The response rate was 45.7%, leading to the final sample size of 127 medical interns and the final confidence interval of 6.4%.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

- Statistical analysis has been done using IBM SPSS software version 22.0.0. All percentages, frequencies and cross-tabulation of the available data were analysed. One-way Anova test and independent samples test were used to define the statistical significance for some data. Missing data were excluded from the analysis.

2.6. Ethical considerations

- The research proposal sent and reviewed by the Committee of Bio-Medical Ethics of the Faculty of Medicine at Umm Alqura University. After approval, the online questionnaire spread to the targeted population. All data that was received in this study is confidential and no personal information has been obtained.

3. Results

- A total of 127 medical interns from the College of Medicine of Umm Alqura University (UQU) of the year 2013-2014 were involved in our study. Around 57.9% of them were males, and 42.1% were females.Regarding the question about how satisfied they were with the quality and quantity of theoretical education they received during their internship year, we asked them to score their answers from 1 to 5 (where 1 is not satisfied, and 5 is totally satisfied); most of them (41.9%) scored “2”, and about (35.5%) scored “3”. The mean is 2.42, and the rest of the answers were distributed between other values “Figure 1”. We found no statistical significance in the relationship between satisfaction of medical interns regarding their theoretical education and gender (“p-value=> 0.05”). When asked to score their satisfaction with the quality and quantity of clinical skills and procedures that they had learned during their internship year from 1 to 5 (1 is not satisfied, and 5 is totally satisfied), most of them responded “3” (35.5%), and about (33.1%) responded “2”. The mean is 2.63, and the rest were distributed between the other values “Figure 1”.

| Figure 1. Satisfaction of medical interns in regard to theoretical education/clinical skills and bedside teaching. (1 = Not Satisfied, 5 = Very Satisfied) |

| Figure 2. Effect of colleagues on medical interns’ satisfaction. (Source of mistreatment/ Source that improves medical intern’s knowledge) |

| Figure 3. The best activity that improves the intern’s overall knowledge |

| Figure 4. Exposure of medical interns to different types of mistreatment |

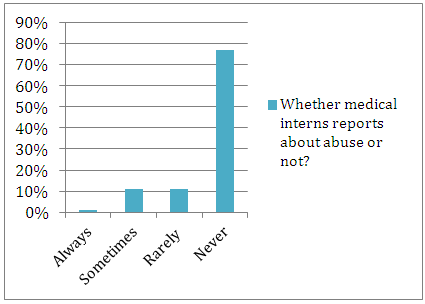

| Figure 5. Reporting the abuse by medical interns |

4. Discussion

- This study was done in order to improve the quality of teaching and the satisfaction of medical interns regarding their internship year at the College of Medicine of Umm Alqura University. Up to 77% of our study population has an intermediate level of satisfaction about what they learned during their internship year. This result appears close to Steven R. Daugherty et al. study that shows that most of the participants had moderate satisfaction.We found in our study that almost one half of the study population agreed that the “residents” were considered to be the best in improving their knowledge during the internship year. This result is consistent with Steven R. Daugherty et al. study, which said that the highest contribution to learning came from other residents. However, residents are also the most common source of abuse that occurs to medical interns, as 76.4% of interns agreed about that, so we can consider the residents to be the most important factor that affects the intern’s satisfaction, either positively or negatively. In our study, we found that 35.5% experienced verbal abuse, and less than one percent (0.8%) experienced physical abuse, which shows a lower incidence in comparison with Rahila Iftikhar et al. study, which shows that 86.6% experienced verbal abuse, and 18.8% experienced physical abuse.Less than one tenth (7.3%) of our study population said that they had a personal experience with sexual harassment, in comparison to Rahila Iftikhar et al. study that was done in the same province of Makkah, at King Abdulaziz University in Jeddah, KSA, which shows a somewhat similar percentage of sexual harassment (8.6%). However, in Mohammed Al-Shafaee et al. study that was done in Oman, the incidence of sexual harassment was higher (24%). One more set of study results from Wolf TM et al. was obtained farther away in New Orleans. This study shows that more than half of the study population received some kind of sexual harassment. Our study has some limitations, as the questionnaires were completed by the participants on their own in separate locations. Hence, the interpretation might have differed. Ideally, the study should have been conducted at a single site under supervision. However, this was not done because it was too difficult to coordinate and get all participants together on a given date. Another disadvantage is the lower response rate, as it can be considered a kind of bias especially if the characteristics and satisfaction degree of non-responders differs from responders. Future studies should employ larger sample size in order to have more precise result that help in enhancing medical interns satisfaction.

5. Conclusions

- Medical interns were moderately satisfied with what they had learned during their internship year. It is possible to improve their satisfaction if we decrease the different kinds of abuse that occur to them and if we improve some hospital activities like morning meetings and seminars. We need more studies to confirm whether or not all these recommendations are effective.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML