-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Education

p-ISSN: 2162-9463 e-ISSN: 2162-8467

2016; 6(1): 1-8

doi:10.5923/j.edu.20160601.01

Judging the Old and the New: Appraisal Systems for Teachers in Pre-Tertiary Education Institutions in Ghana

Irene Akobour Debrah

Faculty of Education, University for Development Studies, WA, Ghana

Correspondence to: Irene Akobour Debrah , Faculty of Education, University for Development Studies, WA, Ghana.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2016 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

This paper investigates the quality of preparation; knowledge and skills given to Teachers, Head Teachers, Circuit Supervisors and District Education Officers for effective appraisal system for the purpose of quality teacher performance and learning outcomes at the basic schools in Tano North and South Districts of Ghana. The study focused on specific elements of education and training such as teachers and education managers’ knowledge in staff performance appraisal, key roles the teachers and education managers were expected to play in the appraisal process, skills and techniques needed by appraisers and appraisees for active involvement in the appraisal process and nature of education and training organized for the teachers and managers. Through multiple data sources, the study revealed that Teachers, Head Teachers, Circuit Supervisors and top management personnel at the District Directorate of Education were not well informed about the current appraisal system. Again, the training was inadequate and lacked the necessary appraisal skills and techniques for effective appraisal process. The skill gaps identified were self-appraisal, peer appraisal, target setting, keeping appraisal journal, data collection and analysis and contributing to one’s own growth and development. The study suggests that the Ghana government should recognize the importance of teacher professional development and invest heavily in staff performance appraisal and development to promote quality teaching and learning at the pre-tertiary institutions.

Keywords: Appraisal, Education, Ghana, Teachers, Reforms

Cite this paper: Irene Akobour Debrah , Judging the Old and the New: Appraisal Systems for Teachers in Pre-Tertiary Education Institutions in Ghana, Education, Vol. 6 No. 1, 2016, pp. 1-8. doi: 10.5923/j.edu.20160601.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Providing quality education to strengthen the human resource base is the hallmark of all educational systems the world over, Ghana inclusive. Educational quality in developing countries has become a great concern because of the need to maintain quality in the midst of quantitative expansion of educational provision (Leu and Price – Rom, 2006). Most of the contemporary writers on “quality education” agree that quality staff performance is critical to effective and efficient service delivery to achieve quality education. To this end, staff performance appraisals are important mechanisms for assuring quality education service delivery. Until 1999, the system for appraising teacher performance in Ghana was based on annual confidential assessments, promotion interviews and reports made by circuit supervisors and officials from the Inspectorate Divisions of the Ghana Education Service (GES). In the schools, the head teachers assessed teacher performance according to the guidelines in the Head teachers’ handbook; vetting teachers’ scheme of work; classroom observation and lesson presentation; teachers’ punctuality and regularity of attendance and quality of pupils work. The head teacher then filled and submitted a written confidential report to the District Circuit Supervisor.The external appraisal of teachers’ performance took the form of inspections by circuit supervisors and other officials from the district and regional education offices. They visited the schools and assessed teachers’ work based on predetermined rating criteria and made judgments concerning the professional capabilities of the teacher. Assessments were done to confirm newly trained teachers who had served their probation, to promote teachers, or to nominate teachers for Best Teachers Award. Another instance where teachers’ work was assessed was when there was a whole inspection aimed at assessing the level of efficiency and effectiveness of the school in promoting the quality of teaching and learning, utilization of instructional time and resources to enhance teaching and learning. These forms of appraisal system were however fraught with challenges which are discussed subsequently.First is the quality of information upon which head teachers and circuit supervisors make assessment of teacher performance. Quality of appraisal information depends on the “multi-source” of information, the frequency of data collection, vigilance and care attached to the process of data collection. For instance, the researcher’s initial interaction with teachers and educational managers revealed that supervision of teachers’ work was slack. Supervisors seldom conducted observation of classroom teaching and inspection of pupils’ exercises. The implication of the foregoing is that the head teacher or the circuit supervisor may not have adequate information on the teacher to complete the report. He or she may have provided information that may not be necessarily correct about the teacher. The actual strengths and weakness may not have been identified for the necessary help to be given by either the head teacher or officers from the district office.The second problem is that teachers seem to have developed a negative perception of the appraisal system because of the confidential nature of the assessment. Teachers revealed that appraisers were subjective, and never involved them in the process. Furthermore, external supervision was scarcely done by officials of GES (Fobih, Koomson and Akyeampong, 1999). The occasional visits had become more routine inspection of the schools and their records. It appeared GES officials did not have adequate time to supervise teachers in the classroom for any considerable length of time. Most of them did not hold appraisal conferences to provide the needed assistance and feedback of competence due to pressure of work. Finally, teachers saw external supervisors as faultfinders who did not give constructive feedback to motivate and assist them improve upon their performance.From the issues raised, it appeared the traditional approach to staff performance in basic schools did little to improve quality of teaching and learning in schools. Moreover, it appeared that both appraisers and appraisees had very little knowledge of quality assurance and staff performance appraisal. In the light of this, a strategic intervention was designed by the Ministry of Education (MOE), through its Basic Education Sector Improvement Project (BESIP), for improving the quality of teachers’ and students’ performance in educational institutions (Ministry of Education, MOE, 1996). Within this framework, a comprehensive performance appraisal system for appraising teachers, ancillary staff and units of educational systems has been in place since 1999. The Ghana Education Service Council launched a new appraisal manual entitled “Staff Development and Performance Appraisal Manual” in December, 1999 to ensure a comprehensive performance appraisal system in pre-tertiary education institutions, (Early childhood care, Pre-school, Junior High and Senior High Schools). The methods and procedures as to how the appraisal system should be carried out by appraisers to ensure that professional development is emphasized in the appraisal process are well spelled out in the manual. As an intervention strategy, one expects that all principal actors should be well prepared and equipped with the needed skills and techniques to ensure that quality education and training is given to teachers and education managers in Ghana. It is against this background that the study is conducted, using the Tano North and South Districts of Brong-Ahafo Region as a case study to investigate the nature of education and training given to teachers and education managers on the new staff performance appraisal in basic schools. Of particular importance to this study are issues such as knowledge, skills and nature of training and techniques given to teachers, head teachers, and circuit supervisors on staff performance appraisal.The former system of appraising staff as explained in the background was characterized by hierarchy and accountability. The appraisers (head teachers, circuit supervisors and district education officers) tend to impose predetermined standards concerning desirable teaching outcomes on the teachers. The whole process was from top down without the active involvement of teachers in the process to improve their own professional development and the teaching-learning process. As observed by Jensen (2011), the process is just an administrative exercise with no feedback to improve student’s performance. It focused on monitoring conformance with routines, record keeping and written reports and treated all teachers alike.Most organizations are now moving away from this evaluative approach to a more participatory and development process where teachers have the independent thinking, reflective practice and ownership of the development of their own personal and professional growth and development (Flores, 2010 and Jensen, 2011). According to Stone (2002) performance appraisal involves the measurement of an individual employee’s performance against a set of criteria providing feedback and creating a development plan. The most commonly quoted definition of teacher appraisal is that formulated by the Appraisal and Training Working Group of the Advisory Conciliation and Arbitration Service (ACAS), anindependent panel on teachers dispute in 1986 asa continuous and systematic process intended to help individual teachers with the professional development and career planning and to help ensure that the in-service training and development of teachers matches the complementary needs of individual teachers and schools (Advisory Conciliation Arbitration Service, ACAS, 1986).The deduction is that performance appraisal is a process, systematic, has a measurement orientation, and is purposeful. In addition, appraisal should be continuous, participatory and developmental in focus. ‘Continuous’ implies that appraisal should not be merely a one-off form-filling exercise, but should be ongoing; ‘Systematic’ implies that the appraisal process should not be haphazard, nor subjective but rather based on evidence accumulated from a variety of sources. It should be well planned, orderly and professionally accomplished; ‘Intended to help individual teachers with their professional development’ suggests that the appraisal process should be about reviewing current practice and performance, structuring ways to improve them, setting specific and achievable targets, identifying training and support needs and considering career progression. All appraisal systems should be sound. In this sense, the methodology and techniques employed should be appropriate, vigorous and ensure accuracy and quality. The appraisal system must be purposeful and must be viewed in relation to the organization’s objectives and designed to suit its culture and particular development objective. These critical features of performance appraisal are a great challenge to appraisers and therefore require thorough preparation and education.Towards the Implementation of Performance Appraisal System: a literature PerspectivePreparations given to teachers and administrators to ensure effective implementation of the appraisal system have long historical antecedents. Gebremeskal, and Tesena (2014) and Boachie-Mensah etal., (2012) for instance, are of the view that the success of the appraisal system depends on the ‘quality’ of appraisers. Appraisers must be experienced, professionally credible and inspire trust and confidence. According to OECD (2009), the effectiveness of the appraisal process relies greatly on the competencies and proper skills of both appraisers and appraisees. Hence appraisers should be equipped with feedback skills, development of research skills, teacher evaluation procedures, good data collection and managing staff development skills.Al-Jammal (2015) and OECD (2009), also suggest that managers should receive training in goals setting, standard settings, conducting interviews, providing feedback, counseling and understanding of instruments development. In addition, OECD (2009) emphasized that the educational authorities should design training packages for schools to ensure the smooth and sustainable implementation of the performance appraisal policy. The areas covered include: leadership management and interpersonal skills; establishing appraisal systems and documentation to record performance expectation and development of objectives. The training should also cover self-appraisal and techniques for professional dialogue, feedback, appraisal interviews and reporting. The use of performance appraisal in employee development, performance improvement, and achievement of the organization’s strategic objectives need to be emphasized.In another related development, Kimball (2002) has spelled out a comprehensive training package designed for appraisers and appraisees to ensure an effective appraisal system. These include: Training for principals and evaluators on appraisers’ manual, group participation, conferencing strategies and exploring alternative sources of data collection. Al-Jammal and Ghamrawi (2013) were critical of the quality of the training of the appraisers. They opine that, professionals appointed to supervise teachers and evaluate their performance, should participate in formal training sessions so as to enhance their knowledge, attitudes and skills related to staff performance appraisal. This could be done through participating in online professional development programs, attending professional conferences and reading professional books and articles. In addition a survey conducted in New Zealand between 1996 and 1999 (Piggot – Irvine, 2003) revealed that short–term training in appraisal was largely ineffective in helping appraisers to sustain the development of the appraisal system. He further challenged managers to redesign their training program for appraisers so that it goes beyond the quick fix, one–day approach. He suggests that there must be a well-planned ongoing training program for appraisers to update their skills and strategies. Complementing Piggot – Irvine’s view, OECD (2009) asserts that developing skills and competencies for appraisers and appraisees takes time and requires a substantial commitment from educational authorities and the main actors involved in the process.OECD (2009) states that to ensure teachers’ active involvement in the appraisal programs, they should be trained, briefed on the process and provided with training modules of the teacher-appraisal process to ensure a shared understanding of how the scheme is to operate. Education and Manpower Bureau (2003) asserts that for appraisal to be purposeful, heads should organize school–based training activities to expose teachers to the rationale and advantages of appraisal, skills in lesson observation and appraisal interview. Again, schools should sponsor teachers to participate in seminars and training organized by the university and other educational institutions on performance management and appraisal. Thus, the training of teachers should include both pre-service and in-service training.Studies have shown that the focus of developmental appraisal is to enable teachers to get involved in their own growth and development. (Flores, 2010, Boachie–Mensah, 2012 and Al-Jammal, 2015). To achieve this, all teachers should be equipped with a set of skills which include; setting achievable goals for themselves and pupils; observation and monitoring; data collection and analysis on performance; diary and journal keeping on performance; self-reflection and deep-self learning and ability to share their experiences with their peers in schools. (Al-Jammal 2015, OECD 2009)Kimball (2002) acknowledges the importance of school-based performance appraisal and development and has emphasized that heads of institutions should be tasked to train their teachers on the standards and procedures of the appraisal system. Heads of institutions should also ensure that all teachers are given copies of the appraisal manual, self-assessment forms and reflection sheets. Fiddler and Cooper (1992) add that the training of teachers should make them see appraisal as a shared process in which teachers have a real responsibility. The training package should therefore, be both theoretical and practical oriented. Practically, appraisees should be made to observe teachers at work as though they are appraisers and thereafter try to come out with a basis for teaching analysis. Also, teachers should be allowed to go through role-playing sessions in which teachers act as appraisers, appraisees and observers. Using these strategies collectively will adequately prepare teachers to understand how the system operates and empower them for effective involvement in the process to reduce appraisal-related tension, defensive behaviour and rater-ratee conflict. The literature suggests that the success or the failure of the staff performance appraisal depends on the quality of appraiser and appraisees’ preparation, education and training. There is a dearth of literature on preparation, education and training by the Ghana Education Service on the current appraisal system, hence this paper sought to fill this gap.

2. Methodology

- Study AreaThis descriptive survey was carried out in the Tano North and South Districts of the Brong-Ahafo Region of Ghana. The study area has 1,053 primary and junior secondary school teachers, 169 head teachers, 13 circuit supervisors, 8 frontline Assistant Directors and 2 Directors at the District Directorates of Education. A sample size of 288 respondents consisting of 243 teachers, 34 head teachers, 6 circuit supervisors and 5 top management persons were selected for the study using random and purposive sampling techniques. Data CollectionTo achieve the objective of the study, the data collection involved three distinct methods. These were interview guide, questionnaire survey and documentary review. Documentary review was important for the analysis on appraisal materials used by trainers for the training. These include staff performance appraisal manual, appraisal forms, self–assessment forms and other relevant materials on staff performance appraisal.Secondly, purposive sampling was employed in identifying those who were directly involved in the process. The study utilizes qualitative data gathered from the participatory research approach. Participatory approaches enable a much deeper understanding of the social dynamics, as well as perceptions of the structure of power, of rights, of cultural change and behaviours (Yaro, 2013).A systematic approach was employed. In all, four semi-structured interviews were conducted for top management staff of the District Directorates of Education and 18 head teachers using separate interview guides for top management personnel and head teachers respectively. The reason for choosing relatively unstructured interviews was to allow for flexibility. In addition, the use of unstructured interviews allowed frank expression of views so as to not betray the trust and relationships we had built together. It also offered me the opportunity to obtain other information that could be of interest to the study. These interviews elicited information about their activities, experiences, opinions and feelings concerning their operations. This also enabled the interviewer to ask respondents to expand on issues which were particularly important to the study. The interview schedules were used to elicit information from the respondents about the knowledge and skills they have received on the appraisal system and appraisal process. Lastly, two separate questionnaires were prepared, one for teachers and the other for head teachers and circuit supervisors. The questionnaires survey focused on preparations given to both appraisers and appraisees towards the new appraisal system.Data AnalysisAfter careful editing, the quantitative data obtained from the household survey was entered into the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS for Windows) for analysis. The quantitative data were presented in frequencies and percentages while the qualitative data were thematically analyzed using Interpretive Phenomenological Analysis. The aim of this analytical approach is to explore the participants’ view to understand and integrate as far as possible, an “insiders’ perspective” on the phenomenon under study (Smith & Osborn, 2003). Following verbatim transcription of all interviews, notes were made to throw light on interesting or significant comments.

3. Results

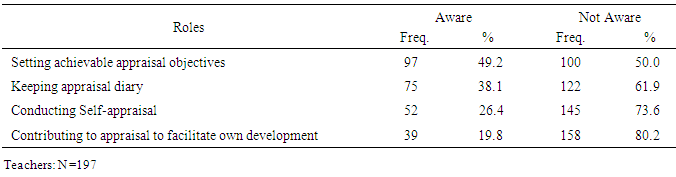

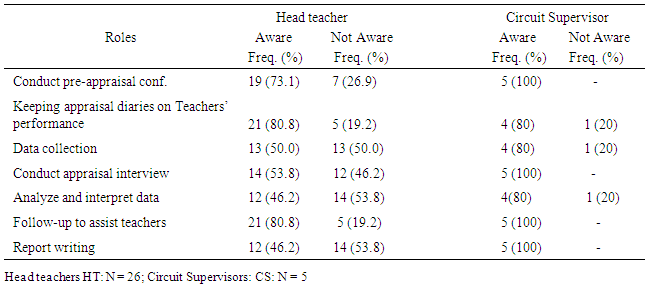

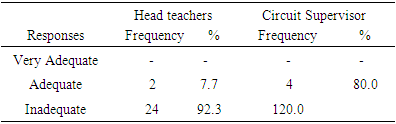

- Teacher Awareness of Expected RolesA number of findings emerged from the study. These are classified into three broad areas: Awareness of teachers, head teachers and circuit supervisors concerning roles they are expected to play in the appraisal process; skills for which teachers, head teachers and circuit supervisors needed training and adequacy of training received. Tables 1 and 2 present respondents’ responses on the roles teachers, head teachers and circuit supervisors are expected to play in the appraisal process. From Table 1, it can be seen that as many as 80 percent of teachers were not aware that they had to contribute to their own development. For self-appraisal, 74 percent of teachers were not aware that they had to keep appraisal dairies on their own performance. About half of the respondents were also not aware that they had to set achievable appraisal objectives.

|

|

|

|

|

4. Discussions

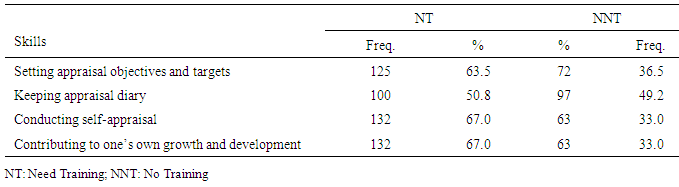

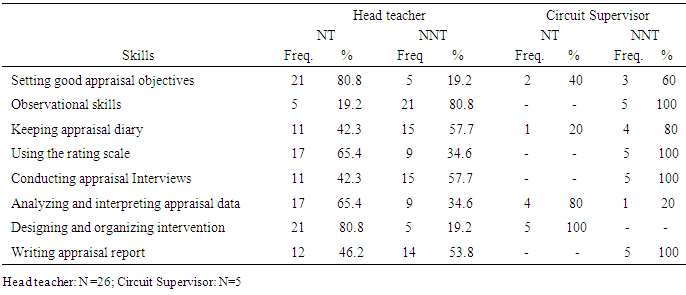

- Knowledge of and Skills Needed for the Staff Performance Appraisal ProcessFor an effective appraisal system, many researchers have emphasized the need for quality and adequate preparation. All principal actors (appraisers and appraisees) should be informed and equipped with the skills and techniques needed for the appraisal process. Unfortunately, a majority of teachers were not informed about the appraisal process. Also, they did not have the necessary skills that would enable them to contribute effectively to the success of the appraisal system. The findings contradict the observation made by OECD (2009) and Manpower Bureau (2003). They emphasized that to ensure the active involvement of teachers in the process, they should be well trained, briefed on the process and provided with written outlines of how the scheme is to operate. Additionally, besides the school–based training activities, some teachers and head teachers were sponsored to participate in seminars and training on performance management and appraisal. The small number of teachers who had been given some orientation on the appraisal supported the statement made by a Assistant Director in charge of supervision that the training of all teachers in the country would be a great burden on GES; therefore, circuit supervisors were tasked to train teachers in their various circuits. It also supports the observation made by Education and Manpower Bureau (2003), that due to financial constraints, principals were tasked to train teachers in the circuits. However, the small percentage of teachers who had the orientation seems to suggest that most of the circuit supervisors did not live up to their responsibility. Also, they did not deem staff performance appraisal as important to quality teaching and learning.The results of the study clearly showed that some head teachers and circuit supervisors have some form of exposure while others have not. These findings support the observation made by the Assistant Director in charge of the Inspectorate Division that with the exception of those appointed after 1999, the rest had been trained. The fact that one circuit supervisor was not trained contradicts the assertion made by the Assistant Director who organized the training that all circuit supervisors in the districts had been exposed to the current appraisal system. It should be noted that each Circuit Supervisor oversees an average of 25 schools in his circuit. The implication is that in each circuit, there are 25 head teachers and at least 125 teachers (if each school has 5 teachers). Consequently, if one circuit supervisor is not well informed, the effectiveness of the appraisal system would be greatly affected.Skills Gap IdentifiedMost teachers need training in target setting, self-appraisal and peer appraisal, contributing to one’s own development, and setting objectives and targets. These skills are among the set of skills which (Al-Jammal 2015, OECD 2009) considers most vital for a successful appraisal process. They observed that the focus of developmental appraisal is to enable teachers to get involved in their own growth and development. To achieve this all teachers should be equipped with a set of skills, which include, setting achievable goals for themselves and pupils; observation and monitoring data collection and analysis on performance; diary and journal keeping on performance; self reflection and deep-self learning.For circuit supervisors and head teachers, the skill gaps identified included setting good appraisal objectives, designing and organizing intervention, strategies, analyzing and interpreting appraisal data, keeping appraisal journals, observational skills, and using the rating scale. These skills are among the most important skills researchers consider very necessary to ensure an effective appraisal system (Al-Jammal 2015, OECD, 2009 and Kimball, 2002). The forgoing discussions and the interviews conducted clearly showed that head teachers, circuit supervisors, senior management were not well informed and equipped with the needed skills for the success of the current appraisal system. This situation is rather unfortunate, considering the enormous role the education managers play in the appraisal process, especially the head teachers (the immediate supervisors) who have to infuse professional consciousness in teachers, raise their level of confidence and guide them to improve their competences and capabilities, as noted by Nyoagbe (1993).Adequacy of Training Received Majority of the head teachers, some circuit supervisors and the Former Director in charge of Training (Inspectorate Division), who organized the training program, agreed that the training was inadequate. A number of reasons were put forward concerning the inadequacy of the training. These include, short period of training, inadequate resources and inadequate funding. Piggot - Irvine (2003) had criticized this short period of training and suggested well planned intensive on-going programs for educational managers on performance appraisal. In support of this view, (Kimball, 2002; Al-Jammal, 2015; OECD, 2009) have spelled out the designing of a comprehensive training package for appraisers and appraisees to ensure effective appraisal. This includes; Training opportunities for new evaluators and monthly principal cluster meetings for superintendent on evaluation standards; problems they encountered; and how to conduct effective appraisal. Al-Jammal and Ghamrawi (2013) have noted that in addition to pre-service training, courses and conferences on appraisal should be organized for professionals appointed to appraise and manage staff development.

5. Conclusions and Policy Implication

- The study established that the management personnel and teachers at the districts had very little knowledge of the current appraisal system and had not been adequately equipped with the necessary skills and techniques in the appraisal process. For teachers, the skill gaps identified included, target setting, self-appraisal and contributing to their own development. The head teachers and circuit supervisors had received some training but the training was inadequate. The skills gap that needed to be addressed include: setting appraisal objectives, data collection, analyzing and interpreting data, designing and organizing interventions and development plan and strategies.Even though the current appraisal system is linked to government policy intervention to improve quality basic education to strengthen the human resource base (Ministry of Education, MOE, 1996), it lacks total commitment from the government. Quality teacher management and development demands heavy capital investment. Unless the government provides adequate funding and materials, this intervention may not be able to achieve the purpose for its establishment. The government must therefore recognize the importance of staff performance appraisal and through the Ministry of Education, budget heavily for the promotion of a quality teacher appraisal system in pre-tertiary institutions. The current quarterly grant of $4.50 for the management of schools appears to be woefully inadequate for the management of staff development and the school. It is very clear that the training program for teachers and educational managers was not well planned, organized and handled by competent experts. Directors (HRMD), GES and District Directors should embark on vigorous appraisal training programs for all teachers, circuit supervisors, head teachers and top management personnel to ensure that they involve themselves effectively in the process.Also, performance appraisal experts should be contracted to train the appraisers and appraisees. The Director (HRMD, GES) should ensure that all pre-tertiary institutions are adequately supplied with materials and resources which include; Staff Development, Performance Appraisal Manuals (1999), appraisal forms, self-assessment forms and manuals, and appraisal development forms. This calls for the proper collaboration of all stakeholders, especially (GES, GNAT, and NAGRAT) in terms of investing heavily in the training of teachers and education managers to ensure quality staff performance appraisal. Finally, Head teachers and circuit supervisors should organize a school-based appraisal training session for newly trained teachers and head teachers who are transferred to the district to equip them with knowledge and skills that would enable them to be effectively involved in the appraisal system.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML