-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Education

p-ISSN: 2162-9463 e-ISSN: 2162-8467

2015; 5(5): 142-149

doi:10.5923/j.edu.20150505.03

Inner Language and a Sense of Agency: Educational Implication

Mehrdad Shahidi

Psychological Aspects of Education-Inter-University Doctoral Program, MSVU, Canada; Faculty Member, IAU-Tehran Central Branch, Iran

Correspondence to: Mehrdad Shahidi, Psychological Aspects of Education-Inter-University Doctoral Program, MSVU, Canada; Faculty Member, IAU-Tehran Central Branch, Iran.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2015 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

Focusing on Archer’s view about agency, structure and reflexivity this article revolved around the educational implications of reflexivity. To apply her theory in educational settings, a three-stage outline was portrayed based on a reciprocal relationship between agency and structure. The outline consists of a rational and realistic view of agency, a developmental map to show how a sense of agency is constructed through inner language, and some strategies to promote a sense of agency in students. Characterizing the modes of reflexivity, it was also argued that any strategy to develop each single mode of reflexivity may affect students’ sense of agency differently and may produce some unexpected social and educational consequences. It was suggested that an educational system should make a balance between all modes of reflexivity and prevent the possible issues such as a tendency to overestimate freedom or the contextual discontinuity.

Keywords: Self-Agency, Inner Language, Modes of Reflexivity, Education

Cite this paper: Mehrdad Shahidi, Inner Language and a Sense of Agency: Educational Implication, Education, Vol. 5 No. 5, 2015, pp. 142-149. doi: 10.5923/j.edu.20150505.03.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Developing and formulating a critical realist perspective about social transformations through reflexivity, Archer (2012) distances from social determinism and structurationism (Caetano, 2014), dualism (Riberio-Teixeira, 2008; Hoefer, 2010) and fatalism (Rice, 2013) in which human’s agency is either denied or it has lesser importance. Exploring the interaction between individuals and societies based on her study in 2003, Archer put forward her main ideas systematically in her book named The Reflective Imperative in Late Modernity (2012). In her theory, Archer (2012) focused on the personal power of reflexivity to demonstrate how individuals have power to monitor, change or develop their social stances and situations by virtue of inner conversation (inner speech) about their personal or social concerns, ideas, values and behaviors.Using some key concepts such as morphostasis, morphogenesis, causal power, structure, reflexivity, and agency, Archer (2000, 2012) explained her ontological views about cultural and structural orders and the relationship between structure and agency, and then she endeavored to solve the old philosophical and sociological equation of ‘structure and agency’. On one side of this equation, there is the concept of free will related to the capacity of rational agents (individuals) to choose a course of action independently and to make their own free choices (O’Conner, 2013). On the other side, the concept of structure represents determinism. Structure also refers to the idea of an ordered or organized arrangement of elements which influence or limit individuals’ choices and opportunities (Bernardi, González, & Requena, 2006; Corsini, 1999; Hoefer, 2010). However, the relationship between structure and agency is seemingly considered as a central issue about social theory (Clarke, 2008). Attempting to find a reliable solution for this issue, it was argued that agency has enough power and potential to generate morphostasis and morphogenesis through reflexivity as a full mediatory mechanism (Archer, 2012; Archer & Maccarini, 2013). In this perspective, the conjuncture between cultural order and structural order forms new situational context in which variety (e.g., new elements and new relations) forces individuals to produce novel ways of understanding, gaining knowledge, and adaptation. In Archer’s theory, it was assumed that any social order, which is related to organizing principles and regulation within society, is affected by human’s agency. However, the underpinning layer of agency is reflexivity by which the alterations in individuals’ social stances can be explained quantitatively or interpreted qualitatively. Furthermore, reflexivity per se has causal power to generate transformations (morphogenesis) and to maintain the status quo (morphostasis). These processes (morphostasis and morphogenesis) determine humans’ everyday situations, contextual continuity or discontinuity. It is also assumed that these processes need to be seen sequentially; that is, in any new transformation, which resulted by morphogenetic configuration, there is morphostasis to maintain the new situation and make it consistentin a changing environment (Archer, 2012). Accordingly, both processes are involved in the transformation of social structures or systems such as educational system.The historical transformation of educational system, which is composed of individuals with on-going, mutual, and synergetic relationships, can be determined through either the analysis of agency (students’ subjectivity and institutional agency) or through the reflexivity as an underpinning layer of agency. Thus, based on the significant role of students’ subjectivity (agency) in educational system, it is assumed that educational system as a social structure should promote the sense of agency in students by creating a balance between agency and concerns through designing rational plans for its policy, theory and practice. This aim needs the following outlines:1) Portraying a realistic and rational picture of agency and subjectivity by using interdisciplinary approach.2) Drawing a developmental map to demonstrate how a sense of agency is developed through inner and external language.3) Designing organized strategies to promote the sense of agency in individuals in a collaborating atmosphere by focusing on the different modes of reflexivity

2. A Rational View about a Sense of Agency

- Scrutinizing subjectivity, agency, personal and social identity (Archer, 2012; Bandura, 2006; Kemp, 2008; McLeod & Yates, 2006), a sense of agency (Freire, 1979), and self-regulation (Bandura, 1991; Carver, Johnson, & Joormann, 2009; Carver & Scheier, 2001; Chow, Lam, Leung, Wong, & Chan, 2011; Corr & Matthews, 2009; Legault & Inzlicht, 2013) reveals that they have common underpinning characteristics; although, to some degreethey are different. Buss (2013) argued that “every agent has an authority over herself that is grounded neither in her political or social role, nor in any law or custom, but in the simple fact that she alone can initiate her actions” (P. 2). This ‘authority’ is what Archer (2012) called the ‘power of agency’ by which individuals can regulate their social, emotional, and cognitive behaviors within different contexts, and also construct their new cultural stances and personal situations. This is what I called ‘a sense of agency’. However, Archer postulated that the power of agency is rooted in reflexivity [inner-language] that is a distinguished property of human being evolutionally. A sense of agency is also defined as a quality that enables a person to initiate intentional actions in order to achieve goals that are valued (Mashford-Scott & Church, 2011). This sense is a matter of individual subjectivity with close relationship with personal identity (Mcleod & Yates, 2006). Although social determinists and biological reductionists sometimes ignore the sense of agency as a distinguished human property (Gallagher, 2011), there are some scholars who demonstrated that the phenomenon of agency is a unique feature of humans manifested in social interactions (Archer, 2012, 2000; Caetano, 2014; Elder-Vass, 2010; Bandura, 2006). This realistic portrayal of agency reveals that individuals in any layer of society (e.g., educational systems, health organizations, family systems and others) are characterized by their own sense of agency, personal identity, self-autonomy, authority or power, and self-regulation that all are seemingly produced by reflexivity using cognitive processes.

3. Drawing a Developmental Map

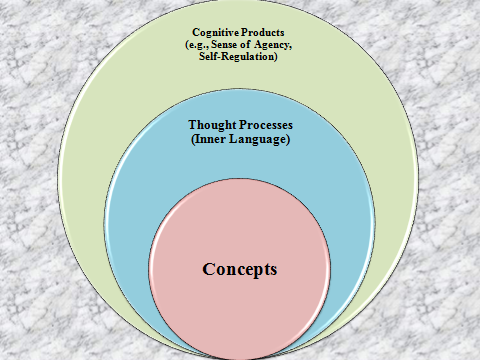

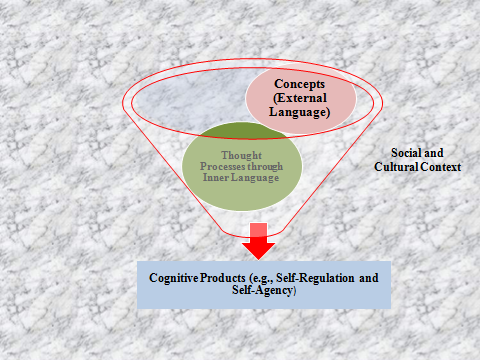

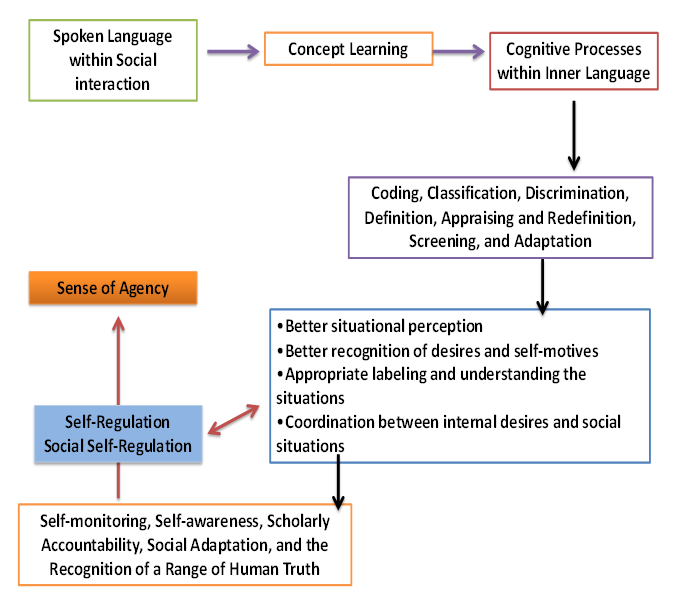

- In addition to characterizethe realistic features of agency, an educational system needs a developmental map to demonstrate how a sense of agency is developed through life-span by inner and spoken language. In this regard, I also took Gallagher’s (2011) perspective into account and argued that Gallagher’s interactional perspective may be a good model to characterize the developmental process of sense of agency. In this model, a sense of agency develops from the early stages of human development through an interaction between individual and environment. This social interaction determines many human’s characteristics such as self-agency, self-regulation, self-awareness and even personality traits (Santrock, Mackenzie, Leung, & Malcomson, 2005; Gillibrand, Lam, & O’Donnell, (2011).Developmentally, at the beginning of life, individuals show undifferentiated physical, emotional, cognitive and social behaviors. The first differentiation of behaviors happen in the first year of life manifesting by body-awareness, object permanence, separation anxiety and other characteristics (Santrock et al., 2005; Bornstein, & Lamb, 2011; Gillibrand et al., 2011). Between the first and third years of life, two significant cognitive systems appear: subjective and objective systems (both consist of a primary form of subjectivity). At this stage, children can show their self-control, self-autonomy and think about their desires and situational concerns. Using the terms “I” and “Me” in their language (e.g., “I don’t need”, “I want that”, “I do it by myself”, “Me too”) reveals that subjectivity (a sense of agency) is going to be formed developmentally (Demetriou, Doise, & Lieshout, 1998; Gillibrand et al., 2011). To complete this process, the interaction between person and each layer of social system has main role. The social interaction, which is facilitated by inner and external language, helps individuals to construct their sense of agency and social identity profoundly (Archer, 2000).As Bandura (2006) and Valloton and Ayoub (2011) demonstrated, language is a major contextual predictor of self-regulation and a major determinant in the evolution of human agency. But, the underlying question is: How does language, particularly inner language, generate a sense of agency? Making some realistic and rational assumptions, I attempted to portray a hypothetical developmental map of self-agency to answer the question: 1) Language is contextual phenomenon (Peters, 2012)2) Vocabulary in language refers to concepts, and the concepts are assumed to be the representatives of thought processes (Margolis and Laurence, 2011). (Figure 1).

| Figure 1. The Layers of Cognitive-Linguistic System |

| Figure 2. The Process of Generating Self-Agency |

| Figure 3. A Hypothetical Process of Constructing a Sense of Agency through Inner-Language. (* In arrows ( ) mean “cause and relationship”) ) mean “cause and relationship”) |

4. Reflexivity, its Modes and Educational Strategies

- Reflexivity is a type of “regular exercise of the mental ability shared by all normal people to consider themselves in relation to their (social) contexts and vice versa” (Archer, 2012 p.1). This also refers to some broad cognitive processes that occur in the form of humans’ inner language. These cognitive processes are defined as thinking and rethinking processes by which people develop the ability of self-awareness and self-understanding of their desires and actions within contexts (Ruch, 2002 cited in Chow et al., 2011). Although this definition of reflexivity is very close to the meaning of reflection, reflexivity refers to human higher cognitive processes such as coding, symbolization, imagination, analyzing, problem solving and other mental abilities that occur through inner language contextually (Plumb, 2008; Chow et al., 2011).The cognitive processes in reflexivity may carry out a total revision of the whole system of self-representations or self-guidance in thinking and self-commitment in actions in relation to contexts (Colombo, 2011). Archers (2012, 2000) argued that these characteristics of reflexivity collectively provide enough potential to replace routine actions and also provide individuals with enough power to construct their life styles based on their concerns in relation to contexts. Considering reflexivity as an inner language or inner conversation, it is supposed that it contains all syntagmatic and paradigmatic properties of language; although, Wiley (2006) believed that inner language has its own weaknesses such as what Vygotsky (1987, cited in Wiley, 2006) pointed out that the “subject of sentence along with its modifiers is usually omitted in inner language” (p. 321). Regardless of such weaknesses, some of the properties of reflexivity may be summarized as the following:1) It provides individuals with an opportunity to address and to balance their concerns in relation to their different engagements with the world (Plumb, 2008).2) It provides individuals with an opportunity to consider themselves as objects of their own thoughts (Colombo, 2011).3) It facilitates coping with the uncertainty of the cultural contexts (Colombo, 2011).4) It involves different cognitive, affective, and experiential processes (Sinacore et al., 1999, cited in Chow et al., 2011; Archer, 2012; Archer, & Maccarini, 2013) in which cognitive processes are predominant. Likewise, Archer (2012) explains that: The affective prompt takes precedence but, in fact, the cognitive plays a bigger role than simply booting out ludicrous inclinations. Although subordinate, cognitive reasoning plays a crucial role in rationalizing affect by working on the verification principle. It provides articulation for the sensed feeling, confirmation for the rightness of that feeling and justification for expressive action based upon that feeling: ‘things in the past that you’d felt and didn’t know very well how to express and then you read and say “yes that’s right”. I like that feeling . . . because sometimes you get emotions and then you think “why did I?”, but then you think “Well, yes, you were right to” (P. 288). 5) Through the cognitive processes of inner language (reflexivity), individuals mull over a problem or social situation, arrange their future ahead, imagine events and possible actions in relation to situation, rehearse their speech, prioritize their concerns and budget their time and money (Archer, 2012; Caetano, 2014).6) The results of Archer’s (2012) studies showed that reflexivity is an age-based or stage-based phenomenon affected by learning. Therefore, it is assumed that the modes of reflexivity are developmental, and may be affected by the stages of education. 7) Reflexivity provides individuals with adaptation processes by helping them to analyze their concerns in relation to different contexts. 8) Although inner conversations are conducted in silence (Plumb, 2008), it involves very fast coding, symbolizing, interpreting and balancing human actions continuously. 9) In contrast to internalization as an important way of interaction with culture and society through which the human’s subjectivity may disappear into structure (Elder-Vass, 2010 cited in Narin, Chambers, Thompson, McGarry, & Chambers, 2012), reflexivity seemingly involves two distinguished cognitive processes of assimilation and accommodation. 10) Reflexivity also generates self-understanding, maintains self-consciousness, occurs within a certain cultural and socio-historical context, creates self-awareness and others-understanding, transforms cultural structures and orders, and it also accelerates the processes of human evolution. 11) It has different modes namely communicative, autonomous, Meta, and fractured modes.Modes of Reflexivity: Reviewing the developmental, cultural and historical features of reflexivity let Archer (2012; Archer, & Maccarini, 2013) to reject homogeneous characteristics of reflexivity. In contrast, she postulated different modes of reflexivity including communicative, autonomous, Meta, and fractured reflexivity. Although all modes can be present in different epoch, each mode of reflexivity may be dominant in a certain historical context (e.g., communicative reflexivity as a dominant mode for traditional or early societies, and autonomous reflexivity for modernity). These different modes of reflexivity determine different stances toward society (Clarke. 2008) and interplay between two sides of the equation of ‘concerns and contexts’. Thus, Archer (2012) believes that the modes mediate between objective or macroscopic feature of social configuration and subjective mental activities. Communicative mode of reflexivity refers to “inner conversations that need to be confirmed and completed by others before they lead to action” (Archer, 2012 p. 13). This mode strengthens the social integration, and it is used by people who tend to maintain the contextual continuity strongly; that is, it fosters morphostasis (Clarke, 2008; Plumb, 2008). With this mode of reflexivity, people seek similarities among the population and situations (Archer, 2012). Although this mode can establish and maintain peoples’ identities (social identity), it create a strong resistance against any possible changes. It may also extend solipsism, a notion by which we have to be a member of somebody’s society in order to understand or know him or her. This notion will maintain peoples’ social identities, but it generates a type of ethnocentrism (Fay, 1996). Autonomous reflexivity refers to a type of inner language that is “self-contained and leading directly to action” (Archer, 2012, p.13). Clarke (2008) argued that goal-achievement is a major characteristic of autonomous reflexivity. This mode is characterized by relying on internal resources, self-directed decision making, taking independent course of action, relying on individual concerns, promoting contextual discontinuity, transforming behavior into action through voluntary conduct, and self-autonomy (Clarke, 2008; Plumb, 2008; Colombo, 2011). An example of this mode can be found in Colombo’s (2011) conversation with Lara (one of the Colombo’s participants in her study in Italy):Colombo: Why did you choose this scientific Lyceum?Lara: Especially, because I had no ideas about my future, and the Scientific Lyceum offers a stronger grounding for a variety of university options. Only for this reason because, honestly, I don’t really have a passion for Maths, just for this reason.C: Who has helped you choose?L: Mmhh, I don’t know, I’d say I’ve been quite free to make my own decision in this respect. I was less free in terms of the actual school, but in terms of what type of school I was very free to choose. Then my parents considered both a Lyceum in Settimo and one in Torino, and finally we decided on this one as it’s closer to home... (P.41).In this conversation most characteristics of autonomous reflexivity can be seen such as self-autonomy, self-directed decision making, taking independent course of action, and relying on own concerns. Meta-reflexivity is another mode that is characterized by self-critique and societal critique (Clarke, 2008). Archer (2012) elaborates most features of meta-reflexives including searching for personal and social reality, being satisfied for this searching, designing projects for future critically, trying to make their project feasible in the external world, and being critique about his or her own effective actions in a society. Since meta-reflexives are skeptical and show less commitment to the society, individuals may feel disconnected from the contexts (Plumb, 2008). Meta-reflexives have enough power to generate emerging structures and networks; although, being critical can make them unstable and inconsistent in beliefs and social norms. In addition to these modes of reflexivity, fractured reflexivity is the last mode in Archer’s (2012) perspective characterized by the lack of purposeful courses of action. Passive agent is another name for this mode that some researchers tend to replace with fractured reflexive (Colombo, 2011; Clarke, 2008). This term, passive agent, is directly related to self-identity by which agency can be meant. These types of people believe that their efforts, which usually come from the personal power, cannot change anything in a society. However, educational system should consider a balance in these modes.

5. Outlining Educational Strategies

- Supposing that the Archer’s (2012) theory of reflexivity has enough capacities to be utilized in an educational system, I attempted to draw some educational strategies from her theory. The following outlines are based on the characteristics and presumed components of reflexivity.1) Since reflexivity happens and develops in socio-historical contexts, and because educational system is per se the most influential and huge organized socio-cultural and historical context, improving a sense of agency in students through reflexivity should be considered as a long-term plan in an educational system. 2) Since self-awareness and others-understanding, as two cognitive components, are generated by reflexivity contextually, an educational system should focus on cognitive and affective plans and techniques such as Personal Art Project which can be implemented at the early stages of education.Personal Art Project Technique: Educators at schools can use this technique to engage students with an oriented inner language in order to promote their self-awareness within a context. This technique is an adapted form of a play therapy technique (Kaduson & Schaefer, 2003). In this activity each student is asked first, to draws his or her own special place (a picture such as a circle or home that shows their context and concerns). Second, they will be asked to write what they know about themselves within the picture. This is a portrayal of self-agency. Then, they should pursue the following steps: A) Analyzing and evaluating their self-expressions about their concernsB) Developing a logical and real argument for themselves by using specific examples / observations or experiences that they have had about themselvesC) Generating new hypotheses about their concerns (these hypotheses can be critical if we focus on meta-reflexivity).D) Verifying the realities of the context (school context, family context or other contexts)E) Making a real and rational relationship between their concerns and the context (or e.g., school context or family context)F) Sharing ideas with others to connect with contexts and making a balance between their concerns and the realities of the contextG) Rehearsing the results through inner-conversations3) Regardless of the fractured reflexivity by which individuals may have confusion in their personal and social identity, the other modes of reflexivity should be encouraged and promoted by educational system. Since focusing on one mode of reflexivity may generate many problems for society, an educational system should make a balance between all modes of reflexivity and prevent their possible issues such as a “tendency to overestimate freedom” (Colombo, 2011 P. 33) and contextual discontinuity (Archer, 2012). These issues can ruin the sense of community that is defined as “a feeling that members have of belonging and being important to each other and a shared faith that members’ needs will be met by their commitment together” (McMillan, 1976 cited in Prezza, & Giuseppina Pacilli, 2007, p. 153). 4) Paying much more attention to meta-reflexivity, which is characterized by self-critique and societal critique, can generate instability and inconsistency in both self-agency and social identity. Although communicative mode of reflexivity can maintain individuals’ identities, (personal and social identity), and it generates contextual integrity and continuity; working scrupulously on this mode may make many resistances to social transformation and development. Therefore, education should consider all these modes in a mutual way.5) Regarding the equation of ‘concerns and contexts’, and to avoid any possible conflict between individuals’ concerns and contexts, educational system should focus on a set of skills by which students can manage and prioritize their concerns in relation to different contexts. Teaching problem-solving skill, time management skill, and encouraging goal achievement or other cognitive skills can promote a sense of agency in students by reducing the conflicts between their concerns and contexts.6) An educational system should also promote students’ engagement with the stratified community of learning in which each layer is a specific context containing its specific realities (entities). Perceiving the community of learning ontologically based on Elder-Vass’ (2010) views will help educators to make a balance between concerns and contexts. To accomplish this strategy, first, school or a community of learning should be seen ontologically as a stratified context. Second, all layers should be seen on one spectrum with inter relationship. This ontological view, which solves the conflict between concerns and contexts, will help students to appreciate the specific realities in each layer, to connect these realities with their own concerns, and to make a hierarchical balance between all concerns and contexts. Since mobility is one of the characteristics of reflexivity, students can easily understand the realities of each context and their own concerns by verifying, elaborating and justifying them. Furthermore, having critical realist ontology will help educational system, specifically adult education, to avoid “conflating entities [...] that need to be held apart to understand the role of adult learning in mediating their interactions” (Plumb, 2008 P. 306).7) Since reflexivity is developmental and an age-based property, education should pay attention to the socio-cognitive development of students. Any plan to promote the appropriate modes of reflexivity should be based on this strategy. For example, Colombo (2011) argued that weak reflexive thinking can occur due to immaturity and egocentrism that are some instances of developmental characteristics of adolescents.

6. Conclusions

- In this paper, I attempted to portray a three-step outline to show how an educational system can utilize Archer’s view to promote a sense of agency in students, and to make a balance between their concerns in relation to educational contexts. I also argued that educational system and all its parts such as policy, theory, and practice should have a realistic perspective of agency and subjectivity, and consider the developmental map of agency since education is a life-long process starting from early childhood. To show how educational practitioners can use Archer’s theory, some sample strategies were outlined. I also suggest an intervention program to promote students self-agency and self-regulation.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML