-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Education

p-ISSN: 2162-9463 e-ISSN: 2162-8467

2015; 5(4): 111-122

doi:10.5923/j.edu.20150504.03

Social Stratification and Mobility: How Socio-Economic Status of Family Affects Children’s Educational Development and Management

Nwachukwu Prince Ololube 1, Lawretta Adaobi Onyekwere 2, Comfort N. Agbor 3

1Department of Educational Foundations and Management, Faculty of Education, Ignatius Ajuru University of Education, Port Harcourt, Nigeria

2Rivers State College of Health Science and Technology, Rumueme, Port Harcourt, Nigeria

3Department of Environmental Education, Faculty of Education, University of Calabar, Calabar, Nigeria

Correspondence to: Nwachukwu Prince Ololube , Department of Educational Foundations and Management, Faculty of Education, Ignatius Ajuru University of Education, Port Harcourt, Nigeria.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2015 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

Social stratification, whether by class or caste, plays a significant role in children’s educational development and management. The socio-economic status (SES) occupied by a family in a given society impacts their ability to pay for school and school supplies as well as attitudes within the family towards education, especially higher education. Much like social stratification and social mobility, SES influences education. In a system open to social mobility based on merit, children and youths will place much more value on excelling in their educational endeavours. This article explores the evolution of social stratification, sociological perspectives on social stratification and the different bases on which stratification occurs. This study adopted survey research design. The population of this study consisted of Faculty of Education lecturers. A total of 111 questionnaires were distributed out of which a convenient sample size consisting 97 (87.3%) was chosen from the 99 questionnaires returned. The instrument used for data collection was a questionnaire designed by the researcher along four-point Likert scale. Data were analysed using Simple Percentage, Mean Score, t-test (t) statistics and ANOVA. The most essential findings of this study is that there are positive tie between children early attendance at school, provision of books and other materials, children attendance at higher quality schools, encouragement in school education, children provision of model English, development of interest in school activities, and children academic and job aspiration and SES of families.

Keywords: Social Stratification, Wealth and income, Education, Occupation / profession, Family background, Gender, Political status, Religion, Race, Social Mobility

Cite this paper: Nwachukwu Prince Ololube , Lawretta Adaobi Onyekwere , Comfort N. Agbor , Social Stratification and Mobility: How Socio-Economic Status of Family Affects Children’s Educational Development and Management, Education, Vol. 5 No. 4, 2015, pp. 111-122. doi: 10.5923/j.edu.20150504.03.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- An academic write up is best when it is opinionated and much effort has been put into it to satisfying that standard. A significant part of the drive to write this article has been that much of what has been written about socio-economic status (SES) of families and its effects on children’s educational development is not consistent with the way researchers, scholars, educators and students actually view SES in relation to children learning outcomes, especially in the Third World. Kainuwa and Yusuf (2013) examined the influence of parents’ SES and educational background on their children’s education in Nigeria. The literature from Kainuwa and Yusuf study revealed that parents’ personal educational backgrounds and economic backgrounds have a significant effect on their children’s education. In addition, Okioga (2013) investigated the impact of socio-economic background on academic performance amongst university students in Malaysia. Using regression and ANOVA analysis, Okioga established relationship between socio-economic background and students’ academic performance. Udida, Ukwayi and Ogodo (2012) study evaluated the influence of parental socio-economic background on students’ academic performance in Calabar, Cross River State, Nigeria. Using a sample of 114 students from five public schools and multiple regression analyses revealed that parental socio-economic background significantly influences students’ academic performance. The study recognized parental profession and occupation as the key predictive variables that influence student’s academic outcome. A similar result was obtained by Ushie, Emeka, Ononga and Owolabi (2012) when they studied the influence of family structure on students’ academic performance in Agege Nigeria. Therefore, researchers in education are responsible for developing a vision and strategy for the understanding and development of education of our children, which this study attempted to explore. For these reasons, the approach adopted in this article, which is tagged “Social Stratification and Mobility: How Socio-Economic Status of Family Affects Children’s Educational Development and Management” does not have definite structure but an interconnected and flexible structure to be able to tease out meaning where necessary. This article identifies the key components of SES and the relationships among these components. It presents a strategy for creating logical, sound and workable relationships among the components of SES for easy comprehension. The approach presented here derives primarily from author’s background and experience in teacher and learning for several years. Consequently, it is written to inform education managers and planners, policy makers, curriculum developers, principals, teachers, and education students (undergraduate, graduate and postgraduate) of the relationship and the advantages of taking this approach to the study of SES and children educational development. Consequently, the objectives of this study are made to order for the study of how socio-economic status of family affects children’s educational development and management, with the view to ascertain the degree to which SES factors impact on children educational attainment. Specifically, the study addressed seven basic objectives:■ Examine how socio-economic status of family affects early attendance at school; ■ Study how socio-economic status of family affects the provision of books and other materials; ■ Examine how socio-economic status of family affects attendance at higher quality schools■ Document how socio-economic status of family affects encouragement in school education■ Investigate how socio-economic status of family affects the provision of model English ■ Explore how socio-economic status of family affects development of interest in school activities ■ Examine how socio-economic status of family affects academic and job aspiration To address the above objectives, seven hypotheses were formulated:■ Socio-economic status of family does not significantly affect children early attendance at school ■ Socio-economic status of family does not significantly affect the provision of books and other materials ■ Socio-economic status of family does not significantly affect children attendance at higher quality schools■ Socio-economic status of family does not significantly affect encouragement in school education■ Socio-economic status of family does not significantly affect children provision of model English ■ Socio-economic status of family does not significantly affect children development of interest in school activities ■ Socio-economic status of family does not significantly affect children academic and job aspiration

1.1. Conceptual Framework

- This study derives its conceptual consideration firmly from the theory of family. The family, as an institution and agent of socialisation, is central to the educational experiences and pursuits of children and youths. Family members are the first teachers of children and help to form their feelings and inclinations towards more formal education. The forms that families can take are era and place dependent – they evolve over time and differ from culture to culture (Ololube, 2012). Despite their differences and the unique contexts in which they are formed, all families globally perform a number of important and similar functions. These are the sexual, reproductive, economic and educational functions (Haralambos, Holborn & Heald, 2004; Schaefer, 2005; Stark, 2007; Ololube, 2011). The institution of the family has been universally acknowledged as the oldest institution in history. It is also universally recognised as the primary agency of socialisation (Ezewu, 1983). Dictionaries describe family as a primary social group consisting of parents and their offspring; one’s wife or husband and one’s children; one’s children as distinguished from one’s husband or wife; a group descended from a common ancestor and all the persons living together in one household. According to Schaefer, (2005) family is a set of people related by blood, relationship or adoption, who share the primary responsibility of reproduction and caring for it members in a society.The analysis of the family from a functionalist perspective involves three main questions. First, what are the functions of the family? The answer to this question deals with the contributions made by the family to the maintenance of the social system. Second, what are the functional relationships between the family and other component parts of the social system? It is assumed that there must be certain degree of fit, integration and harmony between the component parts of the social system. If society must function efficiently, for example, the family must be integrated to some extent with the socio-economic system. The third question deals with the functions performed by an institution or a component part of society for the individual. In the case of the family, this question pertains to the functions of the family for its individual members (Haralambos et al., 2004). Contemporary society generally views family as a heaven from the world, supplying absolute fulfilment. The family is considered to encourage intimacy, love and trust; where individuals can escape the competition of dehumanising forces in modern society and the rough and tumble industrialised world (Daly & Lewis, 2000). To many (Forbes, 2005; Daly & Lewis, 2000; Ololube, 2011, 2012), the ideal of personal or family fulfilment has replaced protection as the major role of the family. In other words, the family now provides what is needed for educational development. Given these functions, family is regarded as a cornerstone of society.

2. Literature Review

2.1. The Concept of Social Stratification

- Social stratification is a product of socio-economic strata (Ololube, 2011). The concept of social stratification is a central concept in sociology. Sociologists have stormily debated social stratification and social inequality, and retain quite different perspectives and varying conclusions. Proponents of structural-functional analysis suggest that social stratification exists in all societies and since social stratification exists in all societies, a hierarchy must therefore be beneficial in helping to stabilise their existence (Hale, 1990). Conflict theorists believe that the inaccessibility of resources and a lack of social mobility is a common feature in many stratified societies. Marxists are of the opinion that stratification means that the working class are not likely to advance socio-economically, while the wealthy may continue to exploit the proletariat generation after generation (Anderson & Taylor, 2002). Social stratification is a sociological term for the hierarchical arrangement of social classes, castes, and strata within a society (Ololube, 2011). It is a structure of inequality that persists across generations, a pattern of structured inequality that creates a hierarchy similar to steps on a ladder or layers of rock and a specific kind of inequality (Ololube, 2012). While these hierarchies are universal to all societies, they are the norm among state-level cultures. The hierarchical and unequal ways in which groups are formed in society affects individual or social groups life chances. It is a natural and voluntary separation according to race, social, economic and political status. According to Schaefer, (2005), the social categorisation of people is often determined by how society is stratified—the basis of which can include—wealth and income. Wealth and income in a society are not distributed evenly. This includes all material asserts — land, stocks, salary, money, wages and other properties, as highly valued materials. Family income is one of the important factors that determine to some extent the duration that the child participates in education (Tomul & Polat, 2013). Tomul and Polat study revealed that students who attend the top universities in the world are from the richest and the most educated families, because higher academic qualification improves their chances of being placed in a superior social class. It is presumed that education breaks all barriers to social advancement. Parents’ occupation and profession play significant role in student’s academic achievement. Some occupations are considered more prestigious than others because they require special training and are highly rewarded, such as academic doctors, medical doctors, professors, engineers, and lawyers (Ololube, 2012). In addition, the family to which a child is born into determines the strata of society to which the child belongs. Children of well-positioned parents tend to ascribe more influence in the society (OECD, 2005). Conversely, the study of Ogunshola & Adewale (2012) revealed that parents’ socio-economic status has no significant effect on students’ academic performance. This is the state of being male or female, boy or girl, including mental and physical disposition, and can determine classification in society. Alade, Nwadingwe and Victor (2014) study depicts that there are significant gender difference in the mean scores of male and female students’ academic performance. The political statuses of families determine their societal placement. If one is of the dominant political class, one tends to be highly respected and retain a lot of influence in society. Same is true in the third world especially in West Africa, the religious belief and affiliation of individuals in a society places some families in better position socially and economically. Religion is a significant activity because many humans depend on it to create shared beliefs, norms and values. As a result, individuals may identify with certain religious organisations in order to gain acceptance into a particular class (Ololube, 2012). According to Ololube (2011), the race (for example, African, Asia, or White) to which one belongs determines one’s social, political and economic class. It is a common phenomenon that some races claim to be more superior to others and as such feel that they are more intelligent than others.

2.2. Types/Systems of Social Stratification

2.2.1. Castes System

- Castes are hereditary ranks that are usually religiously dictated and tend to be fixed and immobile (Schaefer, 2005). According to Ekpenyong (2003) castes are the endogamous and hereditary subdivision of an ethnic group, which occupies a position of superiority or inferiority, when compared with other subdivisions. Caste memberships are determined by birth and influence occupation and social role. Thus memberships are ascribed at birth, and children automatically assume the same position as their parents. Caste systems are associated with, for example, Hinduism in India and Bangladesh (Anderson & Taylor, 2002).

2.2.2. Estate System

- The estate system is commonly associated with the feudal societies of the Middle Ages. The estate system or feudalism required people to work land leased to them by nobles in exchange for military protection and other services. The ownership of land by nobles was central to the system and was critical to their superior and privileged status (Schaefer, 2005). Societies were grouped on the basis of statuses such as nobility or lords temporal, clergy, and the common. Globalisation has altered the caste and estate systems of social stratification and the class system of stratification has gained more prominence (Hale, 1990).

2.2.3. Class System

- The class system is a social ranking system based primarily on economic position in which achieved characteristics can influence social mobility. The boundaries between classes are imprecisely defined and people can sometimes move from one stratum or level of a society to another (Schaefer, 2005). Income inequality and socio-political status are the basic characteristics of a class system.

2.3. Social Mobility

- Social mobility is the degree to which an individual’s family or group social status can change throughout the course of their life through a system of social hierarchy or stratification. Subsequently, it is also the degree to which an individual’s or group’s descendants move up and down the class system. This movement can be the result of achievements or factors beyond control (Grusky & Manwai, 2008; Stark, 2007). Sociologists were fascinated to first learn of social mobility because of the regularity with which people ended up in roughly the same social position as their parents with each passing generation. Despite some intergenerational movement up and down the social ladder, those born into wealthy and influential families are likely to live their lives as wealthy and influential people, while those born into abject poverty are not. This regularity in social mobility, according to sociologists, is the result of inherited wealth, useful social contacts and education.

2.3.1. Forms/Types of Social Mobility

- The forms or types of social mobility have been categorised by sociologists (Bertaux & Thompson, 1997; Grusky & Manwai, 2008; Stark, 2007) as vertical, horizontal inter-generational and intra-generational.■ Vertical social mobility refers to changes in the position of an individual or a group along the social hierarchy. It involves the movement of people from a lower position to a higher position of hierarchy and verse versa. It involves change within the lifetime of an individual to a higher or lower status than the person had to begin with. For example, if a factory worker becomes a medical doctor, a lawyer or holder of a doctorate degree, the person has fundamentally changed his position in the stratification system. Likewise, a woman from a very poor background who weds a wealthy businessperson has also moved up the social ladder. ■ Horizontal social mobility refers to a change in the occupational position or role of an individual or a group without any change in position in the social hierarchy. For example, a university professor who changes job to another university without changing his or her position has not move up or down the social hierarchy. When a rural labourer moves to the city and becomes an industrial worker or a manager takes a position in another company there are no significant changes in their position in the hierarchy. Horizontal mobility is a change in position without a change in status. It indicates a change in position within the range of the same status or movement from one status to an equal one.■ Inter-generational social mobility is a change in status from that which a child began life with the parents or household to that of the child upon reaching adulthood. This is the movement of a person either upwards or downwards on the social ladder. If one starts at a low level, he or she can improve his or her social status by working hard and securing a better job. It refers to a change in the status of family members from one generation to the next. For example a poor farmer's son who rose to become an academic. ■ Intra-generational social mobility takes place within the lifespan of a person. This occurs when a person strives to change his or her own social standing. It refers to the advancement in one’s social status during the course of the person’s lifetime. It can also be understood as a change in social status, which occurs within a person’s adult career, for example, a teacher’s promotion to the position of principal.

2.4. Systems of Social Mobility

2.4.1. Open and Closed Systems of Social Mobility

- According to the Sociology Guide (n.d), a closed system of social mobility is that where norms prohibit mobility. The traditional caste system in India is one example of a closed system. A closed system emphasises the associative character of the hierarchy. It justifies the inequality in the distribution of the means of production, status symbols, power, position and discourages any attempt to change them. Attempts to bring about changes in such a system or to promote mobility may be permanently suppressed. Individuals are assigned their place in the social structure on the basis of ascriptive criteria like age, race, and gender. Considerations of functional suitability or ideological notions of equality of opportunity are irrelevant in determining the positions of individuals into different statuses. However, no system in reality is perfectly closed. Even in the most rigid systems of stratification limited degree of mobility exists (Ololube, 2012). In the open system, norms prescribe and encourage mobility. There are independent principles of ranking like status, class and power. In an open system individuals are assigned to different positions in the social structure on the basis of their merit or achievement. Open system mobility is generally characterised by occupational diversity, a flexible hierarchy, differentiated social structure and the rapidity of change. In such systems, the hold of ascription-based corporate groups like caste, kinship or extended family declines. The dominant values in such a system emphasise equality, freedom of the individual and change and innovation (Ololube, 2011).

2.5. Factors Affecting Social Mobility

- There are some factors that can affect social mobility in any given society according to Ololube (2012, p. 90). They include: ■ Hard work: Hard work can be the key to success. Processes of social mobility depend on it. Those who do not concentrate on hard work in some cases do not move up on the social ladder.■ Inherited wealth: Inherited wealth can also influence social mobility in society. Children, wards, and relatives who inherit money, landed properties and other properties tend to climb the social ladder.■ Level of education: Education is seen as the mover and shaker in the social mobility process. People ascend or descend the class system based on their levels of education. It is presumed that the higher one’s level of education the greater one’s chances of moving up the social ladder and the education of parents according to (Tomul & Polat, 2013) has impact on children’s school achievement.■ Luck: It is presumed that the movement up and down the social ladder depends to some extent on luck. However, movement based on favouritism, nepotism, political or religious affiliation, race, and ethnicity may all be mistaken as movements based on luck (Ololube, 2011, 2012). ■ Marriage: Marriage is a determinant of social mobility. A man or woman from a very poor background who weds a wealthy person may move up the social ladder verse-versa. ■ Societal values and norms: Nigerians are materialistic; get-rich-quick mentalities are now the norm and society seems to value this outlook very much. Those who resent hard work seek to get rich as quickly as possible to enable them move up the social ladder.

2.6. Causes of Social Mobility

- The under listed are some of the causes of social mobility:■ Desire for higher education: People, especially youths, engage in the process of social mobility for the purposes of higher education. They move to urban areas or travel abroad to obtain new and additional qualifications and this move or seeking can affect social mobility. ■ Desire for better living standards: The desire for better living standards can trigger the process of social mobility. People struggle to realise this desire and in the process often migrate from rural to urban areas or travel abroad for greener pastures. This is a common phenomenon in Nigeria. ■ Development of new communications and media: The development of mass and media communication are responsible for social mobility. People now find it much easier to identify and travel to countries which champion social mobility. ■ Geographical environment: In this situation people migrate to areas where the geographical conditions are conducive to their advancement - where the geographical conditions are considered to be good. For example, in extreme winter people may migrate to plain cities. ■ Conducive political and economic situations: In cases where there are conducive and suitable political and economic conditions, people take active part in the process of social mobility. The position and status of individuals continues to change with the progress of the country. This is more evident in developed countries like the United Kingdom, United State of America, France, and Switzerland.

2.7. Positive Effects of Social Mobility

- The under listed are some of the positive effects of social mobility:■ Improvement in living standards: Social mobility brings about improvements in the living standards of people. People change their professions or move from rural to urban areas, which ultimately improve their living standards.■ Improvement in national unity: Social mobility causes people to move to other parts of the country. In doing so they interact with new cultures, which increase social interaction with different communities. On a large scale, such interaction increases national unity and solidarity. ■ Greater affinities for personal freedom: Due to social mobility, level of education increases, which invariably results in an increase in affinities for personal freedom. ■ Obsolete customs: When people interact with new cultures they learn new customs, tradition, and norms. People may adopt certain positive traditions that replace negative or obsolete norms.

2.8. Negative Effects of Social Mobility

- The under listed are some of the negative effects of social mobility:■ Ethnic and cultural problems: Social mobility can have a negative impact on the demography of a territory. It can create a state of collision between the interests of different groups, which, in turn, can create problems of social disorder. The constant standoff between Muslims and Christians in Nigeria is one example. ■ Increases in crime: Social mobility can increase the crime rate. Because of social mobility a taste for lavish lifestyles has been encouraged in people as they forgo hard work for get-rich-quick schemes. In addition, in the absence of the head of the family, children can become delinquent which also leads to increased crime. ■ Unemployment: Social mobility can increase unemployment. In every society, some professions are highly valued. Consequently, people move to those professions in great numbers. As a result of this, they disregard or devalue other older professions which people may no longer want to fill. ■ Unequal division of population: Social mobility can bring about the unequal distribution of population in industrial areas and cities.

2.9. Socio-Economic Status/Children’s Educational Development

- Socio-economic status (SES) in all probability is the most extensively used contextual variable in modern day educational research and has been at the centre of vigorous and active research. However, there seems to be running dispute about the conceptual meaning of SES and the empirical measurement in studies conducted using students (Sirin, 2005). SES is appraised by a number of variables or combination of variables, and has created doubts in the interpretation of research results globally (Singh & Singh, 2014). SES describes a person’s or a family’s position based on hierarchy according to access to or control over a number of value such as income and wealth, political power, and societal values (Macionis & John, 2010; Grusky, 2011).Given differentials in individuals and families in society, there are bound to be differences in the way children attend school and their level of assimilation to academic work. Ezewu (1983) highlighted the following as some of the factors that are responsible for differences in educational attainment:■ Early attendance at school: Research (Ololube, 2011) has shown that families of higher socio-economic status send their children to school earlier than those of lower socio-economic status. They have the means, resources and opportunities to send their children and wards to early childhood education centres and schools.■ Provision of books and other materials: Income is a major determinant in the Nigerian education environment. Parents of higher socio-economic status usually earn higher incomes and value school education more than those of lower socio-economic status. Affluent parents possess the monetary and economic means and willingness to make books and other necessary school materials available to their children and wards.■ Attendance at higher quality schools: Education in Nigeria is expensive and some schools are more prestigious than others in that they attract the most qualified teachers and lecturers. These prestigious educational institutions are usually attended by children and wards of the wealthy because they are costly and it is presumed that these institutions provide the best routes to success in academics and life.■ Encouragement in school education: Families determine the lifestyles that influence the lives of their children and wards. They are either supportive or unsupportive of their children and wards educational development. Children from higher socio-economic homes are usually better prepared for school earlier than children from lower socio-economic homes. ■ Provision of model English: The language of instruction at all levels of education in Nigeria is English. Fundamental to the learning of other subjects in the school curriculum then is the mastering of good English. Children and wards from higher socio-economic backgrounds usually speak better English before entering school. This is, in part, because their parents have better educational backgrounds and speak better English at home for their children to learn from. ■ Development of interest in school activities: As children attend school, it is expected that they show considerable interest in school activities. According to Ezewu (1983, p. 26), children from lower socio-economic status homes show less interest in sporting activities than children from higher socio-economic status homes. Children of higher socio-economic status parents show interest in both academic and extracurricular activities in school.■ Academic and job aspiration: Research has shown that the choice of careers among school children is positively related to the socio-economic status of their parents. In Nigeria, children from higher socio-economic status homes tend to aspire to more prestigious professions in medicine, law, and engineering. Children tend to follow their parents’ line of educational and work endeavours (Ololube, 2011, 2012).

3. Methods

3.1. Research Design

- This study adopted survey research design. The resolve to adopt survey research approach is because it scientifically assisted in the collection of data from identical group of individuals who have the same attitudes, behavior and beliefs. The population of this study consisted of Faculty of Education lecturers that have gained tenure of at least 2 years in four public universities in the South-South geopolitical zone of Nigeria. A total of 111 questionnaires were distributed out of which a convenient sample size consisting 97 (87.3%) was chosen from the 99 questionnaires returned. The reason for disposing 2 questionnaires was because of the way they were filled out and some questions were not answered. The data for the study were collected in the last quarter of 2014.

3.2. Instrument

- The instrument used for data collection was a questionnaire designed by the researcher. The questionnaire was made up of section ‘A’ and ‘B’. Section ‘A’ consisted of the demographic information that includes (a) gender, (b) age, (c) level of education, (d) academic rank and (e) job tenure. Section ‘B’ consisted of seven factors (variables), including their sub-variables: early attendance at school; provision of books and other materials; attendance at higher quality schools; encouragement in school education; provision of model English; development of interest in school activities; and academic and job aspiration. The respondents were required to indicate the extent to which they agree or disagree with the items. The respondents weighed each item on a four-point Likert scale, from (1) strongly disagree, (2) disagree, (3) agree and (4) strongly agree. All items were considered approximately equal value in all the items to which participants responded.

3.3. Data Analysis Techniques

- Responses from the participants’ were keyed into SPSS version 21 software of a computer program and they were analysed using Simple Percentage, Mean Score and t-test (t) statistics. T-test was employed because in probability theory the t-test distribution is one of the most widely used. It is useful because easily calculated quantities can be proven to have distributions that are approximate to the t-test distribution if the null hypothesis is true or false (Ololue & Kpolovie, 2012). One-way-analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to test the relationship between variables and respondents’ demographic information. The statistical significant was set at p < 0.05 to measure if the level of confidence experiential in the sample also exists in the population.

3.4. Validity and Reliability

- This study employed the services of lecturers who were experienced in the construction of instruments in the validation of the questionnaire. Accordingly, the inputs of the experts were included while a few other items were updated. In addition, a pilot test was conducted prior to when the main questionnaires were distributed to determine how respondents understood the items in the questionnaire. The advantages derived from the pilot test were that new insights were got, the errors pointed out were corrected and the total understandability of the questionnaire was measured which helped enrich the final questionnaires sent out to the respondents (Ololube, Kpolovie, Egbezor, & Ekpenyong, 2009). To test the consistency with which the research instrument measures what it is supposed to measure, Cronbach Alpha was employed and a reliability estimate of .818 was obtained. Thus, the instrument was considered to be very reliable.

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Analysis of Respondents’ Demographic Variables

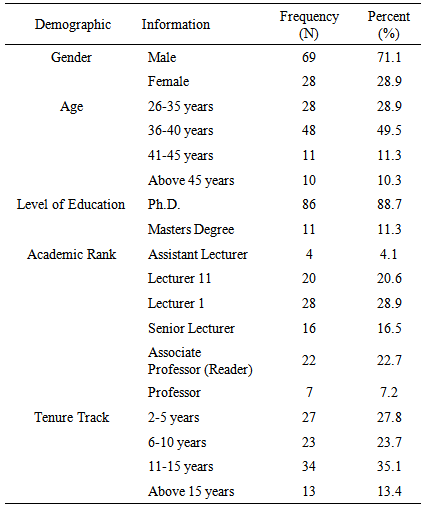

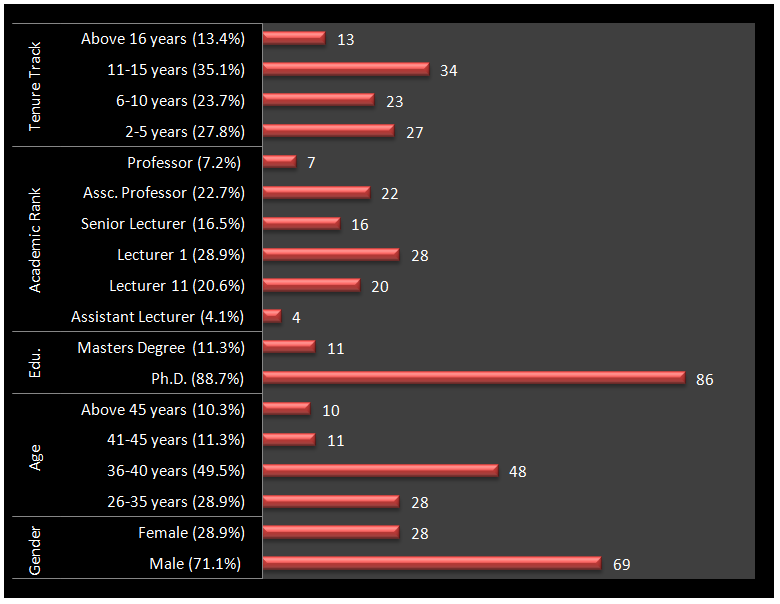

- Results from table 1 and figure 1 revealed that gender recorded more (N = 69; 71.1%) for male, while (N = 28; 28.9%) were female. Respondents that are aged 26-35 years were (N = 28; 28.9%), those who are 36-40 years were (N = 48; 49.5%), whereas those who are aged between 41-45 years were (N = 11; 11.3%), while those that are above 45 years were (N = 10; 10.3%). On respondents level of education, those who hold Ph.D. were (N = 86; 88.7%), while those with Masters Degree were (N = 11; 11.3%). Academic ranks of respondents were grouped into the same six categories. The categories were Assistant Lecturer (N = 4; 4.1%), Lecturer 11 (N = 20; 20.6%), Lecturer 1 (N = 28; 28.9%), Senior Lecturer (N = 16; 16.5%), Associate Professor (Reader) (N = 22; 22.7%), and Professors (N = 7; 7.2%). Slightly above half of the respondents (58.8%) had been employed for between 6-15 years. Below a quarter of the respondents (27.8%) had been employed between 2-5 years, and slightly over a seventh (13.4%) had been employed for over 15 years by their present employers.

| Figure 1. Bar Chart Representation of Respondents’ Demographic Information |

|

4.2. Descriptive Statistics of Respondents’ View on how SES Affects Children’s Educational Development and Management

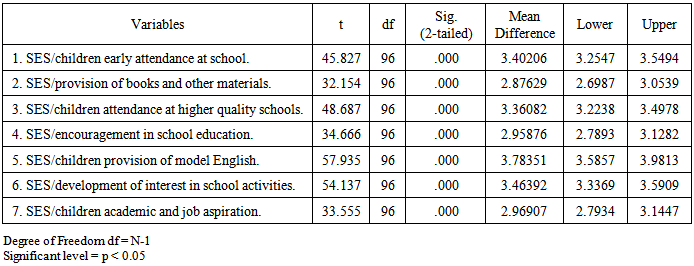

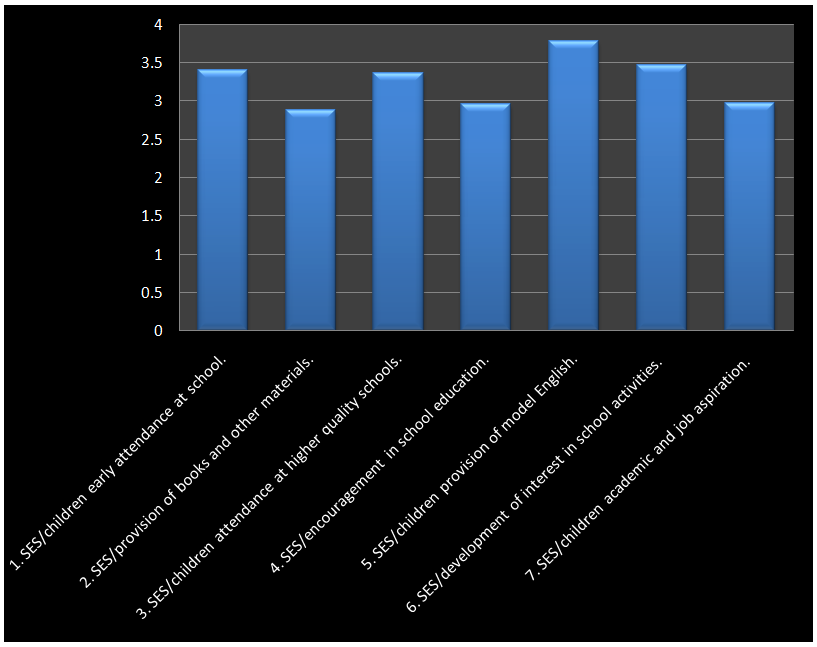

- The second set of analysis (figure 2) was aimed to determine if SES affects children’s educational development and management. Data from the respondents were analyzed using descriptive statistics and the result showed that socio-economic status of family affect children early attendance at school rated high (M = 3.4021, SD = .73), this implies that respondents agree that SES affects children early attendance at school. Second in the level of respondents view was on how SES affects provision of books and other learning materials for children. The result revealed that respondents were of the opinion that SES affects the provision of books and other learning materials (M = 2.8763, SD = .88). Thus, they suggested that children from high SES family have access to reading materials such as books and computer aimed tools. They found high ICTs penetration and usage among children from well-to-do families. Third, was to determine if family SES attend high quality schools. The result depicts that children from high SES attend top line schools and universities (M = 3.3608, SD = 67). Forth, the levels of encouragement, quality of inspection and supervision of children’s academic work rated high as well (M = 2.9588, SD = .84) in the respondents judgment. They found that SES of family affects encouragement in school education. Thus, children are highly motivated to see the need for school education early in their lives because the resources and the level of education of parent on education matters are high. Fifth in the level of respondents view was on how SES affects children provision of model English. The result (M = 3.7835, SD = 69) revealed that respondents were of the opinion that SES affects the children provision of model English. They maintained that children of high SES family tend and have the propensity to speak good and better English because of their early exposure to school education and quality ones at that. The sixth was on how SES of family affects children development of interest in school activities. The data (M = 3.4639, SD = 64) revealed that children influential families develop greater interest in school activities. Respondents were of the view that interests in school activities are of great concern to parents of high SES as a result encourage their children and wards on the need to participate. Finally, it was found that SES of families affects children academic and job aspiration. Overall, the result (M = 2.9691, SD = .87) revealed that respondents were of the opinion that children of high SES aspire for better career part in life. Their job aspiration is tailored along the so called noble and prestigious professions like medicine, law, engineering, and ICT.

| Figure 2. SES/Children’s Educational Development and Management |

4.3. T-test Analysis for SES of Family and Children’s Educational Development and Management

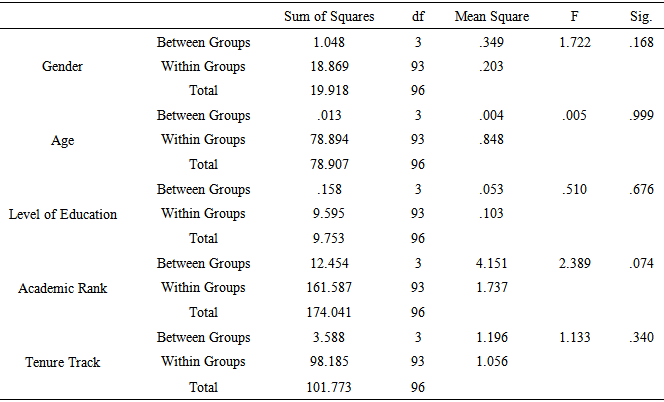

- The third analysis was to test the relationship between SES of families and their affect on children’s educational development and management. Consequently, a two ailed t-test was conducted to test the statistical significance affects that exist between SES of families and children’s educational development and management. The result (table 2) revealed that significant affects exist between SES of families and children’s educational development and management with regards to all the seven hypotheses tested. The respondents were of the belief that SES significantly affects children early attendance at school (t = 45.827, p < .000), and they were also of the view that SES significantly affects children provision of books and other materials (t = 32.154, p < .000). Equally, respondents opinion holds that SES significantly affects children attendance at higher quality schools (t = 48.687, p < .000), as well as, they agree that SES significantly affects encouragement in school education (t = 34.666, p < .000). SES of families they say significantly affects children provision of model English (t = 57.935, p < .000), in as much as they also belief that SES significantly affects development of interest in school activities (t = 54.137, p < .000). Furthermore, respondents opined that SES significantly affects children academic and job aspiration (t = 33.555, p < .000). Cumulatively and unexpectedly, 87% of the respondents as against 13% strongly agree that significant affects exist between SES of families and children’s educational development and management. Thus, all the hypotheses were rejected.

|

|

5. Discussion / Conclusions

- The main rationale for this study is to show how socio-economic status of family affects children’s educational development and management, with the view to ascertain the degree to which SES factors impact on children educational attainment. This study begins with the intent of addressing the lack of comprehensive research evidence on how socio-economic status of family affects children’s educational development and management in Nigeria from the perspective with which we approached it. Also, we tried to make our position as clear as possible and relied on multiple statistical methods of data analyses.In this study and from the results obtained, it is stated that the socioeconomic status of the family has a strong effect on children’s educational development (achievement and performance). However, research (Sirin, 2005) investigations on SES of families revealed this effect to be unswerving while other research (Ogunshola & Adewale, 2012; Tomul & Polat, 2013) outcomes show it to be indirect. In this study, the findings showed encouraging relationship between SES of families and the variables that reflects children educational development.The most essential findings of this study is that there is a positive relationship between children early attendance at school, provision of books and other materials, children attendance at higher quality schools, encouragement in school education, children provision of model English, development of interest in school activities, and children academic and job aspiration and SES of families. The type and quality of school that children attend is significant predictor of academic performance. Studies (e.g., Alade, Nwadingwe & Victor, 2014; OECD, 2005) have made strong case on the influence of the SES of families on children’s educational development, the results from this study yield similar outcomes. Wößmann (2004) found that the socio-economic of families are predictors of student’s success in school. The type of school a child attends at early years of his or her life significant predicts the child’s educational development in the future. Thus, the influence of the SES of family can be said to be a major determinant of a child’s higher education and career aspiration.This article measured and examined the contradictory perspectives on SES of families and their affects on children’s educational development and management, which is essential to the understanding of children’s educational attainment and development. This study supports the need to promote research on SES and the effects on children educational development. This study has guided us evenly through the procedure of data gathering for enriched academic writing from the perspective of a developing country. Every researcher irrespective of location and mission could use the structural plan of this investigation to improve on the theme of SES.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML