-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Education

p-ISSN: 2162-9463 e-ISSN: 2162-8467

2015; 5(4): 95-97

doi:10.5923/j.edu.20150504.01

Attitudes towards Research amongst Clinicians in a Teaching Hospital

Shahla Siddiqui

Consultant, Anaesthesia and Intensive Care, Khoo Teck Puat Hospital, Singapore

Correspondence to: Shahla Siddiqui, Consultant, Anaesthesia and Intensive Care, Khoo Teck Puat Hospital, Singapore.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2015 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

The Singapore anaesthesia faculty exists in Academic restructured hospitals affiliated with a University as well as private practitioners. Although most clinicians are not required to participate in research some may choose to do so. Clinicians in academic centers are traditionally more receptive towards initiating and conducting research, however our standards are non- uniform. Career progression is not directly linked to performance of research although University attachments and tenure ships have certain standards involving research productivity. All restructured hospitals have clinical research support units and there is research support and guidance provided by YLLSOM as well. Despite this ‘voluntary’ research output remains low.

Keywords: Research, Attitude, Knowledge

Cite this paper: Shahla Siddiqui, Attitudes towards Research amongst Clinicians in a Teaching Hospital, Education, Vol. 5 No. 4, 2015, pp. 95-97. doi: 10.5923/j.edu.20150504.01.

1. Introduction

- There is a dearth of clinical research amongst academic and community physicians globally. [1] The majority of clinical interventions presently practiced lack sound evidence. The hurdles usually faced by clinicians are lack of motivation to do research and possible lack of incentives as well. [2] Research requires time and patience above all. Regulatory bodies such as IRBs and lack of funding and proper mentorship has also been known to significantly reduce the chances of busy academics and clinicians from taking up research. [3] In the US physicians face a number of challenges to their involvement in clinical research. Busy patient practices and the necessary billing and reporting procedures leave them with limited time for research. A further obstacle is the lack of a supportive clinical research infrastructure, especially in the form of administrative and financial support [4].Our faculty exists in Academic hospitals affiliated with a University as well as private practitioners. Although most clinicians are not required to participate in research some may choose to do so. Clinicians in academic centers are traditionally more receptive towards initiating and conducting research, however our standards are non- uniform. Career progression is not directly linked to performance of research although University attachments and promotions have certain standards involving research productivity. All academic hospitals have clinical research support units and there is research support and guidance provided by the attached University as well. Despite this research output remains low. Engagement of clinicians in translational research is critical for improvement of the healthcare environment. [5] The aim of this anonymous survey was to elicit anaesthesia clinician’s unreserved responses regarding their feelings towards research in general.

2. Methodology

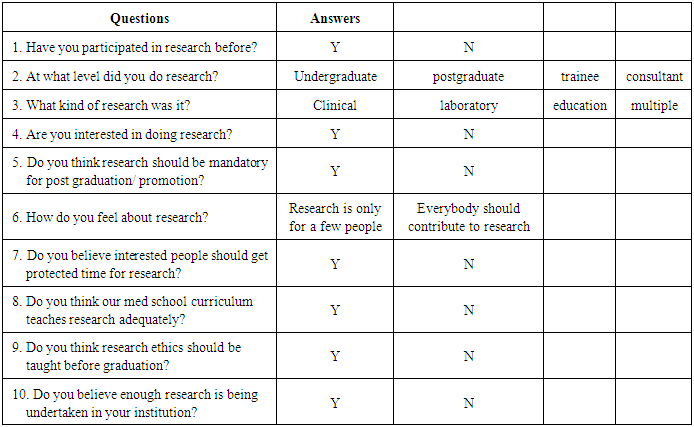

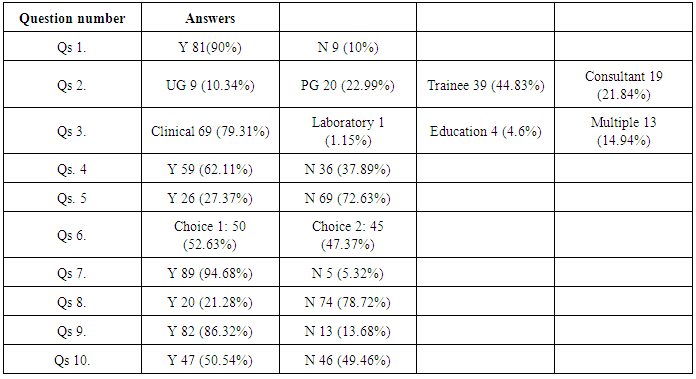

- After institutional and Society approval we approached all anaesthesia clinicians who are members of the Singapore society of anaesthetists via email. They were invited to anonymously participate in a survey (using Survey monkeyTM). There were ten questions asked regarding wide ranging topics related to attitudes towards research. The questions were internally validated by a trial on three participants prior to sending out and amended accordingly. Attached are the survey questions in Table 1 and the tabulated results in Table 2.

|

|

3. Results

- There were 90 respondents (which was a 95% response rate). The participants were a mix of private and public hospital practicing clinicians (consultants). 90% stated that they had participated in research, with most of them having done so as a post graduate trainee (44%). Only 21% of the consultants had been involved in research. 10% stated they had participated as an undergraduate student. Clinical research was the most predominant form of research carried out (80%), followed by 15% carrying out multiple forms of research, 4% educational research and 1% laboratory research. 62% stated they were interested in doing research, but 73% felt that research should not be mandatory for graduation from training or promotions. There was an even divide (50%) about general feeling that ‘research is only for a few people’ vs ‘everybody should contribute to research’. However, most respondents (95%) felt that interested people should get ‘protected time’ for research. 79% felt that medical school curriculum taught research adequately and 86% felt that research ethics should be taught before graduation. Only half (50%) felt that enough research was being carried out at their institution.

4. Conclusions

- This survey aims at greater understanding of anaesthesia clinicians towards research. The response rate was high indicating that the topic is considered important amongst the study population. [6] Even though the majority of clinicans had participated in research most did it during their training years indicating a lesser proportion of seniors participating in research. Our results show that three quarters were interested in research they did not feel it should be compulsory or tied to career progression. The majority felt that researchers should get more time to do research indicating a lack of enough time for most busy clinicians. Teaching of research and research ethics was deemed adequate; however, half identified inadequate research being conducted presently.Through this study we have elicited a response that leads us to believe that greater motivation and training is required in order to inspire more clinicians to contribute towards research and that clinically relevant research is more popular. In order for a research culture to thrive, provisions and mentorship need to be in place from an early stage. A research culture can be cultivated through example setting, role modeling and a fair and balanced reward system. [7] Good quality research requires the presence of a powerful infrastructure. Educators and senior researchers can pave the way through mentorship and coaching. Clinical researchers are often left to conduct such research on their own time and with very little support. [8] The need for clinically relevant research needs the buy in from practicing clinicians in order for evidence to be embraced and improvement of health care. Further studies are needed to delve into possible work life balance issues clinicians may be facing in embarking on research paths.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML