-

Paper Information

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Education

p-ISSN: 2162-9463 e-ISSN: 2162-8467

2015; 5(3): 80-89

doi:10.5923/j.edu.20150503.02

Enhancing Mathematics Performance through Reflection-on-Mathematics-Self-Efficacy and Skill Training in Elementary-School

Sara Katz

Sha'anan Academic College, 7 Hayam Hatichon St. Kiriyat Shmuel, Haifa, Israel

Correspondence to: Sara Katz, Sha'anan Academic College, 7 Hayam Hatichon St. Kiriyat Shmuel, Haifa, Israel.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2015 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

Learning mathematics requires cognitive and meta-cognitive effort. Self-efficacy is a very important component of motivation. High-efficacious students achieve more than low-efficacious students. Therefore, very important in mathematical education is the nurturing of students' self-efficacy. This qualitative action-research on 18 sixth graders implemented reflection-on-self-efficacy-to-learn-mathematics and skill training. Research tools were 20 students’ reflection tasks, 10 non-participant observations, and 15 field notes. The study resulted in students' mathematics high self-efficacy and achievement. The theoretical contribution of this study is the successful intervention that fostered mathematics learning. Enhanced self-efficacy reinforced skill acquisition, which in turn contributed to higher efficacy beliefs, and vice versa.

Keywords: Skill training, Self-efficacy, Self-regulation, Action-research

Cite this paper: Sara Katz, Enhancing Mathematics Performance through Reflection-on-Mathematics-Self-Efficacy and Skill Training in Elementary-School, Education, Vol. 5 No. 3, 2015, pp. 80-89. doi: 10.5923/j.edu.20150503.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Learning mathematics demands cognitive and meta-cognitive efforts. It is logically built in a form of layers of understanding where the understanding of each stage depends on understanding the previous one. Skipping one step or teaching two steps together might lead to misunderstanding resulting in stress or anxiety, which impairs the student's thinking when coping with mathematical problems [1]. An interesting result shows that 17% of the entire population suffers from high mathematical anxiety [2]. In order to learn mathematics, students have to sense its logics. The teacher's role is to make learners believe that they are capable of finding the mathematical logics. Students' beliefs about their capabilities to produce designated levels of performance that exercise influence over their lives are called self-efficacy beliefs.

1.1. Self-efficacy – a Key Factor of Achievement

- Self-efficacy beliefs determine how people feel, think, and motivate themselves to act [3]. Scholars have reported that, regardless of previous achievement of ability, high-efficacious students work harder, persist longer, persevere in the face of adversity, have greater optimism and lower anxiety, and achieve more than low-efficacious students. They approach difficult tasks as challenges to be mastered rather than as threats to be avoided. An efficacious outlook fosters intrinsic interest and deep involvement in academic activities. Such students set themselves challenging goals and maintain strong commitment to them. They use more cognitive and meta-cognitive strategies, and achieve more than those who do not have strong beliefs [4]. In contrast, students who doubt their capabilities shy away from difficult tasks which they view as personal threats. They have low aspirations and weak commitment to the goals they choose to pursue. When faced with difficult tasks, they dwell on their personal deficiencies, and on the obstacles they will encounter, rather than concentrate on how to perform successfully. They lose faith in their capabilities very quickly and fall easy victim to stress and depression [5]. Therefore, of great importance for mathematics education will be to nurture young people who will approach threatening situations in learning mathematics with assurance that they can exercise control over them. It is obvious that competent functioning requires harmony between self-beliefs on the one hand and possessed skills and knowledge on the other [6]. But as people interpret the results of their assignments and judge the quality of their knowledge and skills through these personal beliefs [7], self-efficacy, thus, operates as a key factor of achievement [3, 8]. Self-efficacy has an effect on cognitive and meta-cognitive functioning, such as goal setting, problem solving, decision making, analytical strategy use, self-evaluation, time management, and self-regulation strategies, all of which affect academic achievement [9, 10]. Efficacy beliefs play an essential role in all phases of self-regulation and achievement [11]. Self-efficacy is developed through students' interpretation of their performance, resulting in a positive correlation between self-efficacy and achievement [14].

1.2. Difference between Efficacy Beliefs and Performance

- Learners whose beliefs are exaggeratedly lower or higher than their actual performance act on faulty self-efficacy judgments and might suffer adverse consequences [6, 11, 15]. Students whose self-efficacy is unrealistically low will not take risks. Researchers have found that unrealistic appraisals are common [16, 17]. Inaccurate estimates of self-efficacy might develop from faulty task analysis or from lack of self-knowledge [3]. It is important for teachers to focus on young students' self-efficacy because once positive or negative self-efficacy is established it can be resistant to change [18]. Therefore, this study focused on young sixth grade students.

1.3. Reflection on Mathematics Efficacy Beliefs

- Researchers have planned interventions that helped students overcome their difficulties in learning mathematics, such as improving teaching styles, reflection on mathematics, using interesting mathematics activities, slow and gradual transfer from visual presentations to symbols, visual organizers and instruments, calculators to overcome arithmetic problems, clear and systematic strategy teaching, verbalizing thoughts through talking, writing, drawing the steps they took to solve mathematical problems, interventions that took care of impulsiveness of students, thinking aloud and peer assessment [19]. Yet, many students are still intimidated by mathematics. Studies have shown that reflection enhances meta-cognitive processes such as self-monitoring, self-evaluation, self-reaction, and attribution [13]. Self-appraisal of efficacy is a form of meta-cognition, and efficacy beliefs are structured by experience and reflective thought [3]. This being so, we view reflection on self-efficacy as a forethought process so that the mental processes students will go through, while reflecting on it, over a specific length of time, will have an effect on the processing of their efficacy appraisals. Students' appraisals will undergo a change. Reflection involves investment of time and creative mental effort that culminates in reconstruction of knowledge and gaining new insights [20]. Theorists in the field agree that enhancing students' efficacy beliefs will make a greater contribution to their academic performance than skill training alone, because efficacy beliefs are potentially transferrable [3].The ability to discern, to weigh, and integrate relevant sources of efficacy information improves with the development of cognitive skills for processing information. These include intentional memory, inferential, and integrative cognitive capabilities for forming self-conceptions of efficacy. The development of self-appraisal skills also relies on growth of self-reflective meta-cognitive skills to monitor one’s regulative thought, to evaluate the adequacy of one’s self-assessment, and to make corrective adjustments of one’s appraisals if necessary [3]. Effective intellectual functioning requires meta-cognitive skills such as organizing, monitoring, evaluating, and regulating one’s thinking processes [6]. As students get older, towards the last stage of elementary school age, their efficacy beliefs concerning specific behaviors tend to become shaped and molded. After they develop adequate ways of managing regularly recurring situations, students tend to act on their perceived efficacy without requiring continuing directive or reflective thought [6]. As long as people continue to believe in their abilities to perform a given activity, they act habitually on that belief [3]. Routinizations can detract from the best use of personal capabilities, however, when people react in fixed ways to situations requiring discriminative adaptability. Routinization is also self-limiting when people settle for low-level pursuits on the basis of self-doubts of efficacy and no longer reappraise their capabilities or raise their self-perception. A change occurs only when the person encounters a significant experience. When routinized behavior fails to produce expected results, the cognitive control system comes back into play. New ways of thinking are considered and tested [3]. This being so, reflecting on self-efficacy forces those who tend to avoid thinking and rely on previous efficacy appraisals to rethink and repeatedly revise what is produced in order to fulfill personal standards of quality [3, 6]. This study implemented reflection on self-efficacy-to-learn-mathematics as training, for a long period of time, which will enhance self-efficacy and performance of students.

1.4. Mathematics Skill Training

- Mathematics research shows that self-regulation has an effect on mathematical performance [10, 12]. Self-regulated learners believe that opportunities to take on challenging tasks, practice their learning, develop a deep understanding of subject matter, and exert effort will enhance academic success [22]. In part, these characteristics may help to explain why self-regulated learners usually exhibit a high sense of self-efficacy [23]. These learners hold incremental beliefs about intelligence (as opposed to fixed views of intelligence) and attribute their successes or failures to factors within their control, e.g., effort expended on a task, effective use of strategies [24]. Self-efficacy plays a crucial role in every phase of self-regulation [3, 11, 21], and both self-regulation and self-efficacy involve meta-cognition. Skill training was implemented in a self-regulated learning culture to enhance mathematical achievement. This initiative included: use of technological aids in the classroom, flexible ways of teaching, teacher−student cooperation in learning, teacher considered a coach rather than a sole source of knowledge, nurturing self-efficacy and reducing anxiety, development of meta-cognitive competencies, and high order thinking performance tasks. This culture fits the constructivists’ approach to instruction and learning in that instruction promotes the development of reflective active lifelong learners who make use of knowledge, investigate, construct meaning, and evaluate their own achievements. Task types were usually performance tasks that required integrative thinking processes, elaborations, generalizations, and knowledge production [25, 26].The combination of knowledge of one’s own cognition and action control as well as its evaluation and personal effort is assumed to result in creation. Meta-cognition is a substantial ingredient of creative thinking, as it involves the knowledge of cognition and the regulation of cognition and action [27]. Creative actions might benefit from meta-cognitive skills and vice versa, regarding the knowledge of one’s own cognition and the regulation of the creative process. In our changing technological society, innovations are recognized as the vehicle of economic and social growth and welfare. Promoting these innovations necessitates problem solving, multiple solution assignments, connecting between domains and creative skills [28]. Although mathematicians and mathematics educators agree that creativity plays an essential role in doing mathematics, it is not often nurtured in schools [21]. Creativity in mathematics may be characterized in several ways, such as divergent and flexible thinking, unusual solutions to a given problem [21], connections between domains, or the ability to produce work that is both original or unexpected and appropriate (e.g., useful or adaptive to task constraints) [29]. Working on mathematical tasks may influence not only the mathematical content that is learned, but also how students experience mathematics [30]. Thus, working on appropriate creative tasks might impact students’ perceptions of mathematics as a creative domain. More recently, Sriraman [21] claimed that “mathematical creativity ensures the growth of the field of mathematics as a whole” [21, p. 13]. As such, promoting mathematical creativity is one of the aims of mathematics education. Creative students are successful self-regulated students, who control and monitor their learning environment [29, 31]. Considering that self-efficacy alone will not enhance performance if students lack specific skills needed for specific tasks [21], and that skill training alone might not be sufficient if a student lacks motivation to learn, both reflection-on-self-efficacy training and mathematics skill training in a self-regulated learning environment, in an elementary school were implemented concurrently. Our aim was to follow our students’ self-efficacy to learn mathematics and their performance, while they were undergoing the combined training, to gain insights about the process, describe and interpret them. We asked the following questions:1. What was the nature of the students’ mathematics efficacy beliefs and performance pre-intervention?2. What was the nature of the students’ mathematics efficacy beliefs and performance post-intervention?

2. Methodology

2.1. Participants

- The research population consisted of 18 sixth grade elementary students aged 12-13, in an urban public school in Israel, most of them were students who experienced difficulties in mathematics and had low to average achievements in school.

2.2. Design

- This qualitative action research design was of an inductive and emergent nature, wherein evidence of ongoing processes in the classroom was collected under natural conditions. The role of the researcher as a data collector was integral to the data that emerged. Guba and Lincoln [32] stressed that humans are uniquely qualified for qualitative inquiry. This is due particularly to their ability to be responsive to the clues in the authentic situation, to collect information about multiple factors and across multiple levels, to take a holistic look at situations and try to reveal insights, to process data and generate and test hypotheses immediately, to ask for elaboration and clarification [32]. Throughout the data collection and analysis, an effort was made to capitalize on these qualities to develop a rich perception of the factors that constructed the students’ self-efficacy to learn mathematics and their progress. These methods attempted to present the data from the perspective of the observed group, so that the researchers’ cultural and intellectual bias did not distort the collection, interpretation, or presentation of the data. The qualitative design consisted of systematic, yet flexible, guidelines for collecting and analyzing data to construct abstractions [33]. Listening, observing, communicating, and remaining in the field of the study for a prolonged period allowed understanding and creating an authentic picture of the participants’ thinking regarding their capability to perform mathematical tasks.

2.3. Research Tools

- Research tools were of two kinds: data collection tools and intervention tools, which will be described in this section:

2.3.1. Data Collection Tools

- For data collection, we used three tools: a. Students’ reflection tasks during an academic year. Each student wrote 20 tasks. This tool was used for collecting data as well as for enhancing self-efficacy to learn mathematics. b. Teacher's reinforcement and field notes.c. The skill training was followed by 10 non-participant classroom observations during the academic year.

2.3.2. Intervention Tools

- Reflection-on-self-efficacy-to-learn-mathematics and skill training were used:

2.3.2.1. Implementing Reflection-on-mathematics-self-efficacy Training and Reinforcement

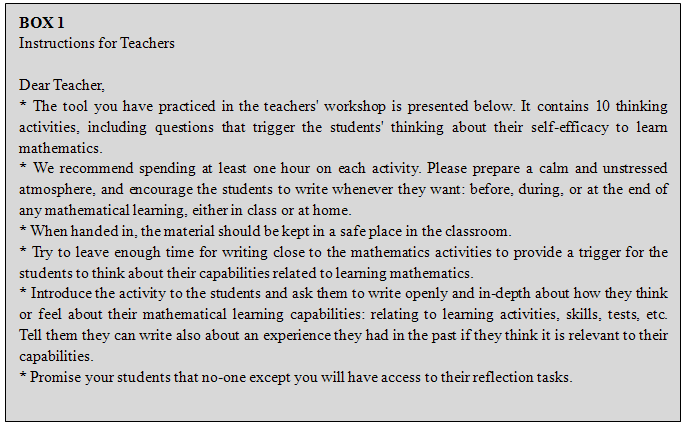

- We started with an explanation to the teachers. Students usually compare their grades to those of other students and those who are labeled less competent expect to find any mathematical task difficult. As they advance through school, they meet other teachers, and if continued to be labeled as weak, they accept the status quo and are either unable or unwilling to change it. Reflecting on self-efficacy will force students to reappraise their self-efficacy and teacher's reinforcement will direct it. Students' self-evaluation of their own learning is critical for appropriate learning and requires nurturing, through enhancing low efficacy beliefs or reducing exaggerated beliefs. Since meta-cognitive processes are involved both in reflection and in developing efficacy beliefs, we view reflection on self-efficacy as potentially helpful training that can nurture efficacy beliefs. Therefore, we would like the teachers to experience it first. The teachers attended a workshop before the start of the academic year, where they experienced reflection on self-efficacy and received instructions.

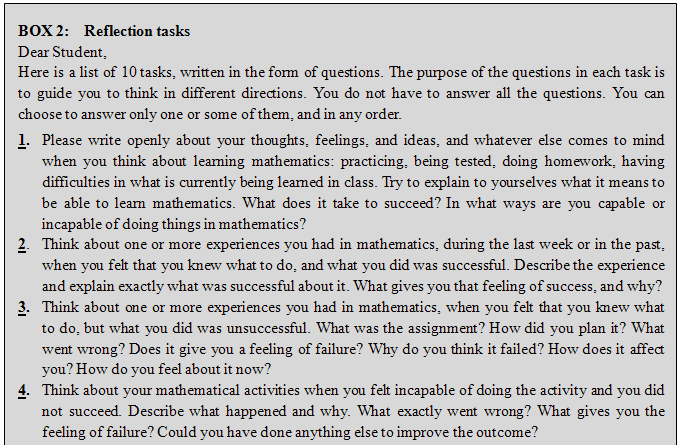

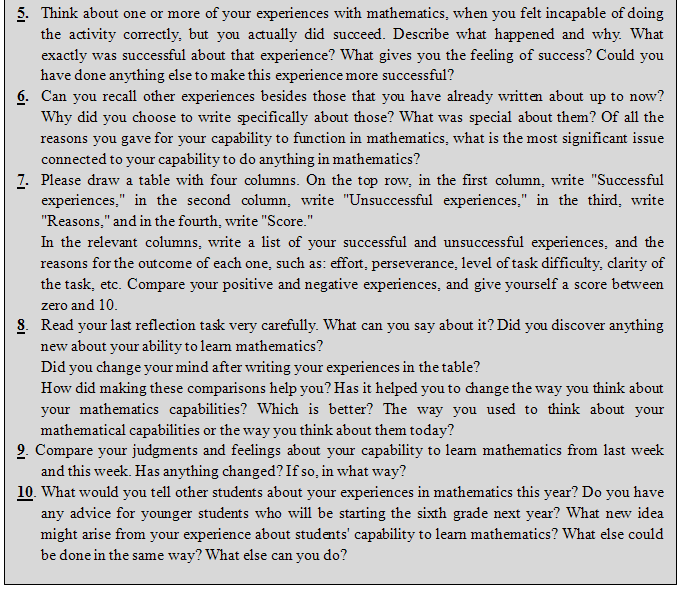

The reflection on the students'-efficacy-beliefs-to-learn- mathematics task:The students were asked to reflect on their self-efficacy regarding learning mathematics. They were helped by guided questions or “Thinking Organizers” [6] that served as means of scaffolding to gradually enhance students' high order thinking. In each reflection task, they could focus on a different meta-cognitive skill, such as selecting important assignments, comparing, self-monitoring, organizing, integrating, evaluating, and regulating thinking processes. The teacher decided when the student was ready to move on to another activity. In some cases, for the student to make progress, the teacher asked him or her to perform the same task again while working on the same meta-cognitive skill. The time that had passed between the first and second performance of the same task (one or two weeks) could improve the student’s high order thinking skills. By the end of the school year, each student had accomplished 20 reflection tasks. Here are the instructions students followed:

The reflection on the students'-efficacy-beliefs-to-learn- mathematics task:The students were asked to reflect on their self-efficacy regarding learning mathematics. They were helped by guided questions or “Thinking Organizers” [6] that served as means of scaffolding to gradually enhance students' high order thinking. In each reflection task, they could focus on a different meta-cognitive skill, such as selecting important assignments, comparing, self-monitoring, organizing, integrating, evaluating, and regulating thinking processes. The teacher decided when the student was ready to move on to another activity. In some cases, for the student to make progress, the teacher asked him or her to perform the same task again while working on the same meta-cognitive skill. The time that had passed between the first and second performance of the same task (one or two weeks) could improve the student’s high order thinking skills. By the end of the school year, each student had accomplished 20 reflection tasks. Here are the instructions students followed:

The teacher wrote encouraging comments and reinforcements on the students' papers. Then the students met with the teacher at group sessions, which were targeted to support and nurture changes in students' efficacy beliefs to learn mathematics. The sessions varied according to the students' progress. Usually, two or three students were present in each session. Sometimes a student met with the teacher alone.

The teacher wrote encouraging comments and reinforcements on the students' papers. Then the students met with the teacher at group sessions, which were targeted to support and nurture changes in students' efficacy beliefs to learn mathematics. The sessions varied according to the students' progress. Usually, two or three students were present in each session. Sometimes a student met with the teacher alone. 2.3.2.2. Implementing Skill Training

- Mathematics skills were taught during the instruction of simple fractions, decimal numbers, percentages, verbal problems, perimeters and areas, volume and angles, in an environment that supported self-regulation. Initiating and reinforcing successful experiences during skill training had didactic and psychological purposes. The teacher was responsible for making sure that the goals would be challenging, but also realistic and gradual, and not too difficult to accomplish. The teacher reinforced the student's success. Since efficacy beliefs are developed through interpretations of performance outcomes, the teacher tried to maximize the impact of mastery experience by providing feedback and encouragement that helped the students interpret those experiences in ways that enhanced their self-efficacy. Students were also encouraged to persist despite their difficulties, and were asked to perform the tasks in a relaxed environment.

2.4. Procedure and Data Analysis

- The data were analyzed using constant comparative analysis and grounded theory techniques [33]. The unit of analysis was a sentence. The units were thematically coded into categories through three-phase coding: initial, axial, and selective coding [34]. Each unit was compared with other units or with properties of a category. Analyses began during data collection and continued after its conclusion. The analysis resulted in a refined list of categories that were developed into conceptual abstractions or themes. The researchers stayed in the setting over time thus enabling interpretation of the meaning in individuals’ worlds [33,34]. Qualitative validity of data gathering was checked by triangulating evidence from the observations against the evidence from all other tools, and when information was repeated several times in different reflection tasks [34]. Qualitative validity of data analysis was checked by comparing researcher results with those of an external rater (n=10), and an agreement was achieved. Member-checks were employed to ensure the integrity of the study. That was performed by obtaining the participants' responses to the researcher's interpretations.

2.5. Ethics

- All parents gave written informed consent to their children's participation. They understood that the study was meant to enhance their children's achievements in mathematics. Privacy was protected and code numbers were used. The participants and parents were allowed to read the results of the analysis, if they so wished.

3. Results

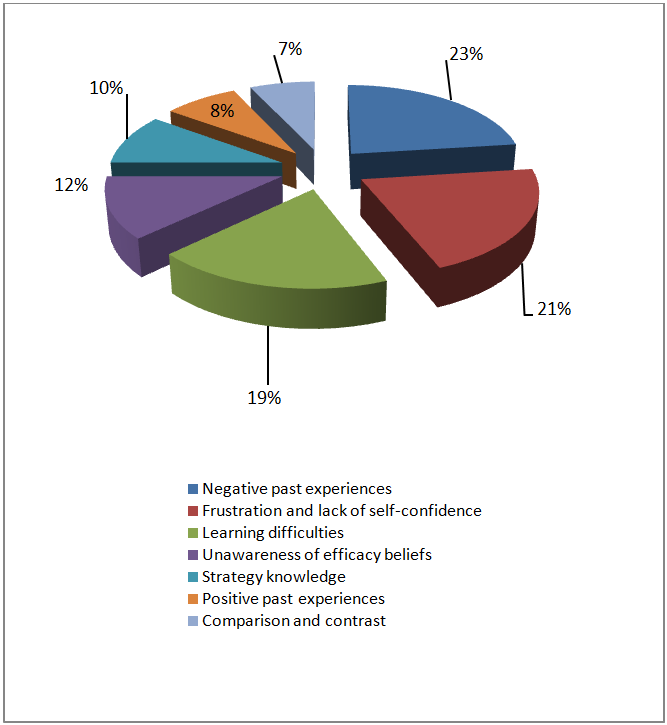

- The students’ reflection tasks, the teacher's reinforcement, comments and field notes, and the non-participant classroom observations during the academic year were analyzed and a variety of themes emerged. Data collection validity was achieved, and Inter-rater agreement on data analysis was 85%. In this section, we will describe this unique intervention by organizing the issues that represent it most fully. Data collection included 10,063 units of evidence. Emerging results were as follows: Result 3.1: Mathematics self-efficacy thinking processes and achievement pre-interventionWe wished to obtain a picture of the students' mathematics self-efficacy beliefs and attainments pre-intervention. Seven themes emerged from this analysis, as illustrated in Figure 1:

| Figure 1. Mathematics self-efficacy thinking processes and achievement pre-intervention |

"I've answered three of 10 questions, It's not worth working on it again". (Observation) The second theme is frustration and lack of self-confidence (21%):

"I've answered three of 10 questions, It's not worth working on it again". (Observation) The second theme is frustration and lack of self-confidence (21%):  "There is nothing I can do, I always fail in mathematics". (Observation)The third theme (19%) contained expressions of learning difficulties:

"There is nothing I can do, I always fail in mathematics". (Observation)The third theme (19%) contained expressions of learning difficulties: "I always ask my Dad. I didn't do it because my Dad was not home". (Observation)The fourth (12%) shows unawareness of efficacy beliefs.

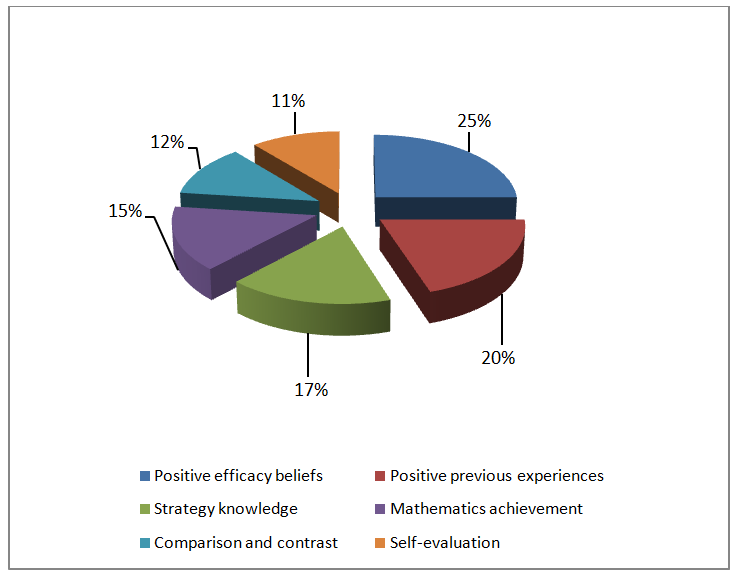

"I always ask my Dad. I didn't do it because my Dad was not home". (Observation)The fourth (12%) shows unawareness of efficacy beliefs.  "I don't know if I can". (Task 2)Strategy knowledge (10%), positive past experiences (8%), and comparison and contrast (7%) were altogether 25%. A quarter of the whole profile was positive, and that gave us a hope to a possible change to occur. This constituted the answer to question 1. Result 3.2: Mathematics self-efficacy thinking processes and achievement post-interventionThe process of the change was gradual and dynamic. To reveal the students' mathematics self-efficacy and performance we performed another analysis at the end of the school year, as illustrated in Figure 2:

"I don't know if I can". (Task 2)Strategy knowledge (10%), positive past experiences (8%), and comparison and contrast (7%) were altogether 25%. A quarter of the whole profile was positive, and that gave us a hope to a possible change to occur. This constituted the answer to question 1. Result 3.2: Mathematics self-efficacy thinking processes and achievement post-interventionThe process of the change was gradual and dynamic. To reveal the students' mathematics self-efficacy and performance we performed another analysis at the end of the school year, as illustrated in Figure 2:  | Figure 2. Mathematics self-efficacy thinking processes and achievement post-intervention |

"I believe I can find a solution to this problem". (Observation)The second theme was recalling previous positive experiences (20%) where students recalled their experiences during intervention.

"I believe I can find a solution to this problem". (Observation)The second theme was recalling previous positive experiences (20%) where students recalled their experiences during intervention.  "I did my homework alone and the teacher said it was correct". (Field notes) The third theme contained descriptions of strategy knowledge of the students (17%), which were better than those of the pre-intervention period (10%). Students did not mention the difficulties they probably had; instead, they let their positive efficacy beliefs emerge.

"I did my homework alone and the teacher said it was correct". (Field notes) The third theme contained descriptions of strategy knowledge of the students (17%), which were better than those of the pre-intervention period (10%). Students did not mention the difficulties they probably had; instead, they let their positive efficacy beliefs emerge.  "You have to calculate the area of the triangle; I know how to do it ". (Observation) The fourth category was their mathematics achievement (15%). They reported that they got good grades in mathematics assignments and that their performance improved.

"You have to calculate the area of the triangle; I know how to do it ". (Observation) The fourth category was their mathematics achievement (15%). They reported that they got good grades in mathematics assignments and that their performance improved.  "We have got good grades lately ". (Field notes)This was the answer to question 2.

"We have got good grades lately ". (Field notes)This was the answer to question 2.4. Discussion

- The purpose of this study was to enhance efficacy beliefs and performance of 18 sixth graders who experienced difficulties in learning mathematics, using reflection-on-self-efficacy-to-learn-mathematics, and skill training. This was an action research which was meant to also enrich the teacher professional insights and development. The purpose of the study was achieved: The combination of skill and reflection training resulted in meta-cognitive awareness, high self-efficacy appraisal processes, and mathematics achievement. In this chapter, we will discuss the improvement of students' efficacy appraisal processes through reflection-on-mathematics-self-efficacy training; the combination of reflection-on-mathematics-self-efficacy and skill training; the role of successful experiences and reinforcement in enhancing efficacy beliefs; and the teacher's construction of new knowledge on her professional development and instruction.

4.1. Improvement of Students' Thinking Processes

- Students' thinking processes improved, new knowledge was built, and learning mathematics became significant. This is in accordance with Schunk and Zimmerman's findings [26]. They could compare and contrast, and evaluated themselves. The reflection activities of every student during an entire academic year mirrored a natural authentic development of their efficacy-beliefs:

4.1.1. Emerging of Self-awareness

- Awareness is a basis for high order thinking process development and is involved in every stage of reflection [20]. At the early stage of writing, in the first task, most of the students, whose self-awareness was low, used intuition and relied on previous appraisals with no use of active deep thinking. We could not call these students' work – a reflection task:

"I don't feel anything, just see numbers all over". (Task 1) Then in the third task, self-awareness emerged:

"I don't feel anything, just see numbers all over". (Task 1) Then in the third task, self-awareness emerged: "My problem is that I always exaggerate about things". (Task 3)

"My problem is that I always exaggerate about things". (Task 3) 4.1.2. Strategy Knowledge Construction and Usage Followed

- Students described how they used skills, what helped them, what should be improved and how. They dealt with strategies of how to approach a mathematics problem, analyze, interpret, and evaluate it. These learning processes have been shown to promote meta-cognitive skills. Mathematics as a way of thinking, a language of symbols, terms, definitions and principles, does not develop naturally like a mother tongue, but must be learned, and demands cognitive and meta-cognitive effort [35].

"I can use a straightedge and compass to carry out this constructions". (Task 20)

"I can use a straightedge and compass to carry out this constructions". (Task 20) 4.1.3. Recalling Previous Experiences

- Recalling positive experiences that the students had during and post-intervention was accompanied by causes of success and failure. The causes were at first extrinsic:

"I failed because mom couldn't help me". (Task 4) They became more intrinsic when the tasks proceeded, we found sentences such as the following:

"I failed because mom couldn't help me". (Task 4) They became more intrinsic when the tasks proceeded, we found sentences such as the following: "I believe that I can make it if I want to very much". (Task 9)Hence students reported that the experiences of success and the teacher's subsequent reinforcements were the main reason for their improved achievements in mathematics. This supports Bandura's theory on mastery experiences as the most influential source of efficacy beliefs because they are predicted based on the outcomes of personal experiences [36].

"I believe that I can make it if I want to very much". (Task 9)Hence students reported that the experiences of success and the teacher's subsequent reinforcements were the main reason for their improved achievements in mathematics. This supports Bandura's theory on mastery experiences as the most influential source of efficacy beliefs because they are predicted based on the outcomes of personal experiences [36].4.1.4. Comparison and Contrast Process

- In the comparison and contrast tasks, they made real progress. From being unable to distinguish between relevant and irrelevant information, they were able to perform a divergent comparison and contrast using tables and describing experiences in various mathematics theorems or situations. The comparisons and contrasts were accompanied by mindful judgments involving reasonable and critical thinking, which generated knowledge construction:

"When I saw my friend's exam, I was frustrated. Then I thought about all my failures and

"When I saw my friend's exam, I was frustrated. Then I thought about all my failures and  successes in mathematics since the beginning of the year, and I realized that I’ve made

successes in mathematics since the beginning of the year, and I realized that I’ve made  a lot of progress, so I’m OK after all". (Task 19)

a lot of progress, so I’m OK after all". (Task 19) "Look, these two areas are not the same". (Observation)

"Look, these two areas are not the same". (Observation)4.1.5. Self-evaluation and Self- judgment

- By the end of the year, self-judgment, self-evaluation, and conclusion drawing were well-organized and clearly expressed, containing plans and relevant operational proposals for the future. The continual reflection efforts were intense, although admittedly, it was not an easy task to accomplish. Reflection was active engagement in a genuine self-discourse from which new knowledge was built and new goals were set.

"I realized that I have to work more. I am not so good at it yet". (Task 16) Their conclusions referred to the changes they underwent, expectations, and emotions:

"I realized that I have to work more. I am not so good at it yet". (Task 16) Their conclusions referred to the changes they underwent, expectations, and emotions:  "I changed my way of thinking, I believe in myself. I expect more from myself "! (Task 20) Conclusions also referred to the cause of the change:

"I changed my way of thinking, I believe in myself. I expect more from myself "! (Task 20) Conclusions also referred to the cause of the change: "It is because you made me think". (Task 19)A student who said at the beginning of the year:

"It is because you made me think". (Task 19)A student who said at the beginning of the year: "I can do almost anything". (Task 1)became more realistic at the end of the year:

"I can do almost anything". (Task 1)became more realistic at the end of the year:  "I feel more self-confident. My capability is not so high; it is average". (Task 18)Our experience showed that these students needed firm beliefs of self-efficacy to turn concerns into effective learning, as one student said:

"I feel more self-confident. My capability is not so high; it is average". (Task 18)Our experience showed that these students needed firm beliefs of self-efficacy to turn concerns into effective learning, as one student said: "I didn't fail in mathematics. I failed in my thoughts and attitude". (Task 20)Low self-efficacy at the beginning of the year resulted in almost no learning and practice, causing failure, which in turn caused low self-efficacy. When self-efficacy was raised:

"I didn't fail in mathematics. I failed in my thoughts and attitude". (Task 20)Low self-efficacy at the beginning of the year resulted in almost no learning and practice, causing failure, which in turn caused low self-efficacy. When self-efficacy was raised: "I'm in another place today regarding my attitude to math. There is no way I'm going to fail".

"I'm in another place today regarding my attitude to math. There is no way I'm going to fail".  (Task 20)The students’ creative abilities were improved, and some students expressed a change in attitude to their own mathematical competence and were more willing to engage with unknown or challenging mathematical tasks. This group of students earned average and high grades by the end of the year. Their grades improved from very low to average and high, which was a real success for all of us.

(Task 20)The students’ creative abilities were improved, and some students expressed a change in attitude to their own mathematical competence and were more willing to engage with unknown or challenging mathematical tasks. This group of students earned average and high grades by the end of the year. Their grades improved from very low to average and high, which was a real success for all of us. 4.2. The Combination of Reflection on Mathematics Self-efficacy and Skill Training

- Reflection involves awareness at every stage, which serves as a basis for high order thinking process development. Evidence was found showing that meta-cognition has an effect on mathematical performance [37]. Students with low self-awareness used intuition and relied on previous appraisals with no use of active deep thinking:

"I talked to myself over and over again, mathematics is not for me, I know". Reflection is an inner talk of the learners with themselves and with various sources of information [6]. The students' conclusions based on skillful reasoning were the ways they interpreted themselves. Habitual reflection on self-efficacy might be used as a tool for nurturing high order thinking processes, which are needed for mathematical learning. The possibility of nurturing self-efficacy appraisals opens new windows to changing biased systems of many students in mathematics. Reflection and skill acquisition complete one another. When skills are acquired, they serve as a basis for positive efficacy beliefs, which in turn, motivate students to acquire more advanced skills, and higher order mathematics thinking tasks, that result in higher self-efficacy and vice versa [6].Results show that the students made efficient use of information, developed a deep understanding of the subject matter, exerted effort to achieve mathematics success.

"I talked to myself over and over again, mathematics is not for me, I know". Reflection is an inner talk of the learners with themselves and with various sources of information [6]. The students' conclusions based on skillful reasoning were the ways they interpreted themselves. Habitual reflection on self-efficacy might be used as a tool for nurturing high order thinking processes, which are needed for mathematical learning. The possibility of nurturing self-efficacy appraisals opens new windows to changing biased systems of many students in mathematics. Reflection and skill acquisition complete one another. When skills are acquired, they serve as a basis for positive efficacy beliefs, which in turn, motivate students to acquire more advanced skills, and higher order mathematics thinking tasks, that result in higher self-efficacy and vice versa [6].Results show that the students made efficient use of information, developed a deep understanding of the subject matter, exerted effort to achieve mathematics success.4.3. Initiating and Reinforcing Mastery Experiences and Positive Feelings

- Initiating and reinforcing successful experiences and positive feelings in the mathematics classroom had psychological purposes. Feeling calm rather than nervous and worried when preparing for and performing a task leads to higher self-efficacy. The teacher wrote encouraging comments on the students' reflection task papers, and when the students met with the teacher, she discussed the situation with them and reinforced them also orally. The proficiency of the first successful performances during intervention, created new mastery experiences, which provided new information, which was processed to shape future efficacy beliefs. Greater efficacy led to greater effort and persistence to do more, and to create new mathematics solutions, which led to better performance, which in turn led to greater efficacy. This supports Bandura's theory [3] showing how mastery experiences contribute to efficacy beliefs and performance. Children's knowledge of their performance capabilities might be inaccurate, so the teacher's feedback at that level was intended to encourage them. Since efficacy beliefs are developed through interpretations of performance outcomes [3], the teachers' role was to maximize the impact of mastery experience by providing feedback and encouragement that helped students interpret those experiences in ways that enhanced self-efficacy. And indeed, students reported that the experiences of success and teacher's reinforcements were the main reason for their better achievements in mathematics. This supports Bandura's theory on mastery experiences as significant predictors of self-efficacy [36]. The students' rich descriptions, especially in their last tasks, were accompanied by positive emotions, and a desire to control learning and take risks. Positive moods activated thoughts of past accomplishments. It is through the students’ feelings about their performances that their efficacy beliefs are developed, resulting in a positive correlation between SE and achievement [14]. This finding supports Bandura’s theory on emotions or feelings as another important source of self-efficacy [3, 38]. Students were also encouraged to persist despite difficulties, and when performing their tasks, they were supplied with relaxed environments.

4.4. The Teacher's Construction of New Knowledge on Her Professional Development and Instruction

- As an action research, the teacher kept reflecting on her work; she learnt to improve her instruction; she became flexible and ready for changes; she tried to understand her students and their needs; she became more self-efficacious as a teacher; she cooperated with colleagues and asked experts questions when she encountered problems. Once again she realized the importance of the self-efficacy construct as a predictor of performance in learning mathematics in particular, and in education and research in general. The role of emotions, moods and physiological states in enhancing efficacy beliefs was crucial and therefore should not and was not ignored or given up. These conclusions have implications on many dimensions of our lives as learners. And most of all, she realized that a change was possible. She succeeded in initiating successful experiences that led the students believe in their capabilities and become better students of mathematics; She gained new insights on her own teacher-efficacy. Today she knows that she can help change student perspectives regarding learning. It was hard but satisfying.

5. Conclusions and Implications for the Future

- This research targeted one major area related to enhancing mathematics performance through reflection-on-mathematics-self-efficacy training and skill training of elementary-school children. Results showed that students went through various self-efficacy appraisal processes and experienced positive efficacy beliefs that ended in better performance.

"I can learn mathematics, and I'm quite good at it". (Task 19) During the formative period of children's lives, the school functions as the primary setting for the cultivation of social validation of cognitive capabilities, which is needed for mathematical learning. Here, their knowledge and thinking skills are continually tested, evaluated, and socially compared. When they master their skills, they develop a growing sense of their intellectual efficacy. One of the fundamental goals of school is, therefore, to foster children's efficacy beliefs and self-regulatory capabilities to promote successful mathematics learning [35, 39]. Enhancing efficacy beliefs as early as possible in teaching mathematics is a real challenge for mathematics teachers [40].The possibility of nurturing self-efficacy appraisals by implementing reflection on self-efficacy while training mathematics skills opens new windows to changing biased systems of many students of mathematics and enhancing their achievement. This experience creates an increasingly broader educational opportunity for every student who has experienced failure in the past to become efficacious and to achieve mathematics success. Mathematics instructional systems will benefit if reflection on self-efficacy plays an essential role in any teacher's program, enabling student−teacher interaction, time investment, and creative mental effort that will force students to rethink and repeatedly revise their appraisals to achieve self-imposed standards of quality, as happened in this experience. This will enable students to become self-regulated learners, and will contribute to better performance [41]. It is recommended to use this intervention to foster attainments in various levels of classes for the benefit of students as well as teachers.Reflection is an inner talk, which is the main process of self-regulated learning and high order thinking, where learners communicate with themselves and with their sources of information; it is their evaluation and criticism of the way they explain their world:

"I can learn mathematics, and I'm quite good at it". (Task 19) During the formative period of children's lives, the school functions as the primary setting for the cultivation of social validation of cognitive capabilities, which is needed for mathematical learning. Here, their knowledge and thinking skills are continually tested, evaluated, and socially compared. When they master their skills, they develop a growing sense of their intellectual efficacy. One of the fundamental goals of school is, therefore, to foster children's efficacy beliefs and self-regulatory capabilities to promote successful mathematics learning [35, 39]. Enhancing efficacy beliefs as early as possible in teaching mathematics is a real challenge for mathematics teachers [40].The possibility of nurturing self-efficacy appraisals by implementing reflection on self-efficacy while training mathematics skills opens new windows to changing biased systems of many students of mathematics and enhancing their achievement. This experience creates an increasingly broader educational opportunity for every student who has experienced failure in the past to become efficacious and to achieve mathematics success. Mathematics instructional systems will benefit if reflection on self-efficacy plays an essential role in any teacher's program, enabling student−teacher interaction, time investment, and creative mental effort that will force students to rethink and repeatedly revise their appraisals to achieve self-imposed standards of quality, as happened in this experience. This will enable students to become self-regulated learners, and will contribute to better performance [41]. It is recommended to use this intervention to foster attainments in various levels of classes for the benefit of students as well as teachers.Reflection is an inner talk, which is the main process of self-regulated learning and high order thinking, where learners communicate with themselves and with their sources of information; it is their evaluation and criticism of the way they explain their world: "I talk to myself and then I decide what to think and what to do. I convinced myself that I'm good

"I talk to myself and then I decide what to think and what to do. I convinced myself that I'm good  in solving verbal problems, this is how I made it".

in solving verbal problems, this is how I made it".ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- I would like to acknowledge the Shaanan Academic College for financing this study.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML