Fisseha Motuma

Kotebe University College, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia

Correspondence to: Fisseha Motuma, Kotebe University College, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2015 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

Abstract

The purpose of this research was to explore multiracial prospects and challenges in multiethnic school learning. The research employed observation, interview, focus group discussion and questionnaire to gather data from preparatory students and teachers of Menelik II and Dejazimach Wondirad Secondary and Preparatory Schools, in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, in the academic year 2014/15. It employed systematic and stratified random sampling techniques in which it covered 206 sample students out of 2800 targeted student population and 60 secondary and preparatory school teachers, that was, 75% of the focused teacher population of the schools. The research primarily emphasized on qualitative descriptions of data through content and thematic analysis. Moreover, the analysis was complemented by tabular and graphic descriptions. The result reveals that the major multiracial prospects and challenges for the students to express their own opinions are: fear of self expression, lack of multicultural responsiveness, inadequacy of exposure to multicultural accommodative environment, fear of being politicized, complexity of the existing ethno-linguistic and cultural diversity, the time-honored nature of teaching methods, and conceptual and attitudinal challenges. In contrast, the apparently existing opportunities are the existence of constructive views about cultural diversity in education, the inclusive attempts of school mini media services, the celebration of a special school culture day and the feeling of liberalism. In a nutshell, teaching in a multiethnic and multicultural setting demands the need to build up a system of shared learning practices, and inter-reliant relationships between schools and the communities at large.

Keywords:

Multiracial, Prospects, Challenges, Multiethnic

Cite this paper: Fisseha Motuma, Multiracial Prospects and Challenges in a Multiethnic School Learning: (Menelik II and Dejazimach Wondirad Secondary and Preparatory Schools in Focus), Education, Vol. 5 No. 1, 2015, pp. 26-38. doi: 10.5923/j.edu.20150501.05.

1. Introduction

Research findings have witnessed that teachers have passed through dramatic changes regarding how to teach academic subjects. The target instruction has been developed and shifted from focusing on teacher-centered traditional approach to promoting and maximizing interactive and communicative approaches (Malamah- Thomas 1987). The idea of learning by doing through expressing and reflecting one's feelings and opinions, and learning from differential experiences have come to be more favoured over a mere simulation of predetermined learning behaviors (Celec-Murcia 1991). What is more, negotiation of differences in opinions or thoughts is becoming more privileged over rote memorization of contents of a subject of study (Malamah- Thomas, A. 1987; Banks & Banks 2001).More recently, it sounds that different scholars and educational researchers tend to magnify the huge contribution of students’ diverse socio-cultural experiences to achieve meaningful academic success (Ovando, Collier & Combs 2003; Hollins 2008). As a result, many of them emphasize the need to organize, exemplify and contextualize school lessons within the students’ immediate socio-cultural values and life realities. Creating a favorable classroom environment where students play their own role in the learning process is believed to be given priority (Gallos & Ramsey 1997). In other words, the role of active classroom talks or interactions performed by students has been taken as a substantial and effective ways of learning (Malamah- Thomas 1987). Classroom discussions, therefore, are being taken as pivotal tools for successful learning (Banks & Banks 2001; Hollins 2008). Otherwise, how is it possible to reach students’ multiple cultural, social and personal life profiles? What else should be done to empower students to exercise their own learning potentials to exploit the most out of what they already have? As we live in a world dominated by multiple diversities, the cultivation of equity, respect and tolerance among all students should be the central goal of a school in multiethnic and multicultural societies (Banks & Banks 2001; Hollins 2008). One reason is when students exercise free interactions and intercultural dialogues, they develop tolerance and the habit of listening to each other through respecting differences. In addition, as Seelye & Wasilewski (1996:12), state “Most of us in today’s world find ourselves in multicultural surroundings. Some of us enter a multicultural environment every time we open our front door and step out onto our block and cruise around the neighbourhood.” Seeing as we live, learn and work with people of various backgrounds, nurturing students’ multiculturally constructive attitudes and communication skills are practically imperative. Banks & Banks (2001) and Hollins (2008) have had the idea that when students are exposed to diverse life experiences, they become in a better position to explore more sensitive socio-cultural issues with little counterproductive reactions and anxieties. They also increasingly get insight into the beliefs and life stories of others through internalizing tolerance and exercising negotiations of differences within cultural contexts. This helps students who live and learn in a world of suspicion and divisions to clear their doubts about others with different identities (Gay 1997). The point is, as to Mey (2009:395), developing multicultural abilities become increasingly“…essential for peaceful co-existence, mutual tolerance, necessary understanding in [the school] and in other walks of life in the increasingly global, and yet in many places increasingly diversified world.”Stated differently, the periodically addressed reason to inject the perspectives and ideas of multiculturalism into formal schooling is, on one hand, to clear an individual’s self-doubt and misconceptions about others’ socio-cultural values and practices (Cheng 2004). On the other, to help individuals acknowledge the existence of others and see others with different identity marks as partners rather than as rivals (Taylor 1994; Sliwak 2010). In effect, respecting racial and socio-cultural diversities in school learning is meant to ensure the prevalence of a system which guarantees all inviting academic contexts where individuals experience the habit of solving differences through interpersonal and inter-cultural dialogues, discussions, open reflections and negotiations of differences in thoughts (Ovando, Collier and Combs 2003). Schools in multiracial and multiethnic setting should be places where students feel secured and in no doubt to reject rejections and prejudice, and to celebrate diversity (Sliwak 2010; Sinagatullin 2003; Hollins 2008). As students develop multiracial and multicultural competence, they could easily succeed in their after school life. Illustratively, Miller, Kostogrize and Gearon (2009:3), citing European Commission (2008:3), have pointed out, multicultural communication skills and experiences are practically important because: “…it may increase [citizens] employability, facilitate access to rights and services and contribute to solidarity through enhanced intercultural dialogues and social cohesion.”

2. Statement of the Problem

In the words of Gallos & Ramsey (1997: xii), All evidences, however, points to the reality that teaching students of multicultural backgrounds effectively is difficult.--- it is more than teaching content or objectively describing a set of issues. It requires understanding students’ cultural as well as social life experiences. It questions our institutions and polices, values and behaviors, definitions of truth and equity, choices and omissions, self-images and professional roles. It is important to note that, on one hand, it is widely accepted that there is almost no better environment than a school setting for students to learn and experience how to respect each other, live together and benefit from each others’ differential cultural and social life experiences (Gallos & Ramsey 1997; Hollins 2008; Banks and Banks 2001). On the other hand, research findings have shown that there have been significant cases in which schools tend to establish their own culture of teaching (Hollins 2008; Sinagatullin 2003). Still, in some other cases, it has been reported that some students are less likely to communicate their thoughts or feelings or to talk about their differences plainly owing to some barriers such as fear, uncertainty, misconceptions and limitations to the value of social and cultural differences for academic learning (Gay 1997; Banks & Banks 2001; Taylor 1994). Correspondingly, Gay (1997), Banks & Banks (2001) and Hollins (2008) argue that schools where racial and cultural discrimination prevails hurt students’ feelings and self-images that can last lifetime. This could negatively affect students’ goals, ambitions, life choices and feelings of self-worth. Possibly, some more barriers to learning may exist either because they may be linked to the accustomed school system, culture of teaching, the teachers’ own values of cultural issues, diversity, or it may be linked to the students’ own behaviors, or it may be stemmed from outside the control of the school.As commented by Gay (1997) and Hollins (2008), if a student lacks the access to exercise the behavour of tolerating and appreciating cultural and opinion differences, and if, on the other hand, his/her opinions lack acceptance, it could lead the individual to misunderstandings and confusions. Even worse is that the student may be forced to acculturate or accept other’s opinions or beliefs at the cost of own individuality and identity. In some cases, the student may flounder between cultures without a specific sense of belonging to anyone (Gay 1997). For Seelye and Wasilewski (1996:19), the main challenge in teaching culturally and linguistically diverse students is put as: ‘The great challenge of our time is to view or not to view cultural and linguistic diversity as a resource rather than as a problem. All students need to communicate their differences and learn to appreciate who they are.’ It means the primary reason why learners need to use their own thoughts and prior information is to learn how to think differently and develop multiple perspectives in the learning process. Contextualizing the scholarly views, the researcher conducted a pilot study to check out the planned research project at the actual school setting. In this survey, an interview and a focus group discussion (FGD) were held with some senior school teachers teaching at Menelik II and Dejazimach Wondirad Secondary and Preparatory Schools, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. It was found out that a number of informants were likely to address the need to take an immediate action in order to acknowledge and entertain socio-cultural diversities in school learning. One of a senior teachers pointed out that “…I have learned from experience that in teaching students to be all-round and rational in their speech and manner, there is no substitute for experience of different cultures. Sometimes, I personally see confrontations among some students and I think the main question seems just the question of ‘KNOW ME!’” In much the same way, another senior teacher, explained the case as:” In some cases, we face students who appear self-centered and more of expressive perhaps because what they think and say is right and unchallengeable….. It seems they experience little counter reactions from others. So, is there any other way out except improving their multicultural proficiency?” More remarkably, another senior teacher has described the issue as: I have learned from my years of school teaching experiences that there exists a sensible gap concerning how we view or value the motive to recognize and respect multiracial and multicultural perspectives in school learning. I could say some of us talk much about the pros of multicultural education and school. Nevertheless, on the ground, our social life practices show that many of us are seemingly more of ‘culture-blind’. You see, I myself feel that I have limited voice on my own self-image. That is, I was not grown up, and still, I am not in a culture which encourages an individual to see the self as a resourceful and competent person in a school life. And so, I try to reflect and practise the same story during schooling. It means, if the practical school reality exhibits such cases, how could my students acquire the behaviour and experience of valuing multiracial and multicultural views and life realities in the process of learning? So, we need a paradigm shift in our pedagogy, and so a lot needs to be done!It is, thus, highly likely that a school environment where cultural diversity is not aptly recognized and respected could negatively affect the cultural, personal, psychological and social development of the students (Gallos & Ramsey 1997; Banks & Banks 2001; Hollins 2008). And this, perhaps, leads the students to a vicious circle of frustration and failure. After reviewing the critical contribution of students’ cultural experiences to school success, Irvine (2003) has argued that teaching culturally diverse students is essentially a matter of bridging the classroom academic practices to the students’ diverse cultural and life experiences. More than ever, as Irvine puts it: “I believe that students fail in school – not because their teachers do not know their content, but because their teachers cannot make connections between subject-area content and their students’ existing mental schemes, prior knowledge, and cultural perspectives.” (p. 47).Even more to the point, Sinagatullin (2003: 83) has remarked that the commonly held philosophy: “We may sacrifice our ethnic and cultural identity for the grandeur of the nation “is irrelevant and inappropriate in multiculturally oriented schools and societies.’ That is to say, students should not be put in a condition in which their diverse socio-cultural assets and lived experiences become neglected just to meet predetermined school requirements. Typically, in countries like Ethiopia, where multi-ethnicity and multiculturalism is an everyday encounter, schools should entertain cultural values in school learning. Ethiopia has, for example, approved cultural policy in 1997 which assures equal access to culture for ‘all nations, nationalities and peoples of Ethiopia’. Article 39/2 of the constitution of the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia states: 'Every nation, nationality and people in Ethiopia has the right to speak, to write and to develop its own language; to express, to develop and to promote its culture; and to preserve its history' (Council of Ministers of FDRE, Oct. 1997). To circulate multicultural values of nations and nationalities, one element of the cultural policy reads: ‘Cultural themes shall be included into the educational curricula with the aim of integrating education with culture and thereby to shape the youth with a sense of cultural identity’ (Ibid). It is, thus, reasonable to explore and specify multiracial prospects and challenges in multiethnic school learning to ensure that all citizens could enjoy meaningful and measurable learning outcomes and equal school success.

2.1. Objectives of the Study

This study tried to magnify that school learning should focus on ensuring an inclusive environment which guarantees all students a safe and sound condition where everyone can exercise own thinking openly. It capitalizes on the point that the learning practices should encourage all students to maximize their full potential of differences. Putting differently, the study aims at publicizing that schools should be places where students learn and experience the habit of acknowledging the presence of others in all their speeches and acts. Specifically, this research sought to explore and identify multiracial prospects and challenges in multiethnic school learning. It attempted to answer these research questions:1. What opinions and understandings do teachers and students have about the opportunities and challenges of multiracial and multicultural existence in school learning?2. What should a school need to fulfill to secure constructive multicultural prospects in which students benefit from the increasingly diverse school population?3. What measures need to be taken to empower students to value and celebrate the contributions of multiple socio-cultural life experiences to academic learning?4. How is it possible to overcome the challenges arising out of building up citizens’ notions of the role of multicultural-focused school learning to influence nation-wide attitudes?

2.2. Significance of the Study

In countries like Ethiopia, where cultural diversity or multiculturalism is a matter-of-fact of school population, exploring and specifying multiracial prospects and challenges in multiethnic school learning could give us better insights into how the differences in cultures, thoughts and life realities need to be valued in the schooling system. Besides, the findings of this research could offer us the opportunities to look into ourselves and our school systems and then question our taken-for-granted behaviors, beliefs and academic practices regarding the contributions of multicultural resources and experiences to school learning.

2.3. Operational Definitions of Some Important Terms

The meanings of some of the key terms used in this paper are defined as follows: 1. Multiculturalism: the thinking, values and attitudes we attach to multicultural existences that strive to ensure equitable rights and access to all school services and resources.2. Multicultural Education: An equity education that values students’ diverse cultural and social life backgrounds as decisive resources for school success. 3. Multicultural school learning: the attempts to implement inclusive school instructions and learning practices so that all students regardless of their diverse cultural differences express their own thinking and lived experiences differently. 4. Prospects: Own outlooks or perceptions about the existence and life of others. 5. Challenges: barriers or constraints that interfere in the efforts to practise multicultural responsive school instructions and learning practices. 6. Opportunities: favourable conditions that facilitate the attempts to validate multiracial and multicultural values in school learning.

3. Design of the Study

3.1. Population, Sampling and Representation

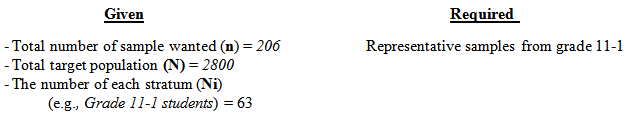

The focus groups of this study were the teachers and students of grades 11 and 12 at Menelik II and Dejazimach Wondirad Secondary and Preparatory Schools in Addis Ababa in the academic year 2014/15. The total student population of grades 11 and 12 of the two schools was 1480 and 1320 respectively, which altogether was 2800. The reason to select the schools was that the two schools were one of the very populated schools and so there could be found students of diverse socio-cultural and ethno-linguistic backgrounds. And the motive to choose these grades was that students learning in these grades were believed to have better school life experiences and socio-cultural exposures as compared to students of other grades. As the total targeted student population of the school was grouped into two grade levels, that is, grade 11 and 12, it was, first, necessary to specify the total number of representative samples to be taken from each grade level. Thus, to determine the total sample size to have been taken from each of grade 11 and 12 students, the formula for stratified random sampling, that is, n/N x Ni, (Wiersma 1995:292) was applied:Where n = Total number of sample wanted- (206 students)  N = Total number of target population- (2800)

N = Total number of target population- (2800)  Ni = the number of each stratum size (e.g. total number of grade 11 students, i.e.1480) Based on the above formula, 109 students were required from the grade 11 sections, whereas 97 students were determined to be taken from the grade 12 sections. Note that it was decided to round-off every digit to the nearest whole number to avoid fraction numbers.The grade 11 student population of the schools was grouped into 22 classes in which each, on average, consisted of 63 students. The grade 12 student population was arranged into 19 classes, in which each, on average, consisted of 69 students. As the target population was grouped into 41 sections, it was decided to apply the formula for stratified random sampling to specify the representative samples of each class. Accordingly, to determine the number of representative samples to be taken from each subgroup (for example, from Grade 11 sections), the same formula was applied.

Ni = the number of each stratum size (e.g. total number of grade 11 students, i.e.1480) Based on the above formula, 109 students were required from the grade 11 sections, whereas 97 students were determined to be taken from the grade 12 sections. Note that it was decided to round-off every digit to the nearest whole number to avoid fraction numbers.The grade 11 student population of the schools was grouped into 22 classes in which each, on average, consisted of 63 students. The grade 12 student population was arranged into 19 classes, in which each, on average, consisted of 69 students. As the target population was grouped into 41 sections, it was decided to apply the formula for stratified random sampling to specify the representative samples of each class. Accordingly, to determine the number of representative samples to be taken from each subgroup (for example, from Grade 11 sections), the same formula was applied.  That means the study involved five students from each of grade 11 classes, which altogether were 110 sample students. Using the same formula, the study involved five students from each of grade 12 classes that were totally 95 students. Finally, to determine the individual student to have been taken from each specified grades and classes of the schools, systematic random sampling was used. To apply this, first the complete name list of each class was collected from classroom teachers. Then, the formula N/n = k, (Ibid), was applied to decide the interval of the individuals to have been selected from each class’s name list, that is: N = Total population of a group\class n = the number of sample to be taken from a given group/classK = a common factor used to determine the interval of individuals in the name list The study has also included 60 teachers, which was 75% of the targeted teacher population teaching at grades 11 and 12 at Menelik II and Dejazimach Wondirad Secondary and Preparatory Schools.

That means the study involved five students from each of grade 11 classes, which altogether were 110 sample students. Using the same formula, the study involved five students from each of grade 12 classes that were totally 95 students. Finally, to determine the individual student to have been taken from each specified grades and classes of the schools, systematic random sampling was used. To apply this, first the complete name list of each class was collected from classroom teachers. Then, the formula N/n = k, (Ibid), was applied to decide the interval of the individuals to have been selected from each class’s name list, that is: N = Total population of a group\class n = the number of sample to be taken from a given group/classK = a common factor used to determine the interval of individuals in the name list The study has also included 60 teachers, which was 75% of the targeted teacher population teaching at grades 11 and 12 at Menelik II and Dejazimach Wondirad Secondary and Preparatory Schools.

3.2. Data Collection Methods

The study employed four data gathering instruments: observation, structured interview, focus group discussion (FGD) and questionnaire with different types of items. To collect written data from the sample teachers and students, the researcher prepared some questionnaires with open-ended and multiple choice items. Both of the questionnaires were planned and developed to directly focus on: (1) determining the potential challenges to implement multicultural responsive school learning practices, and (2) identifying the nature of multiracial and multicultural views in school learning. On the other hand, structured interview and focus group discussion were also designed to try to fully investigate the opinions of the teachers regarding multiracial prospects and challenges being confronted in multiethnic school setting.

3.3. Data Analyses Techniques

The study employed quantitative and qualitative methods of data analysis techniques. To analyze the data collected through the open-ended questionnaires, first, a content analysis was completed. Through this, a set of frequently addressed common themes were identified and tallied, and then, reorganized for further analysis and interpretation. The data gathered through observation and structured interview were discussed, compared and analyzed with the responses to the questionnaires administered to the teachers and the students. The results of the data gathered through observation, structured interview and focus group discussion were mainly used to triangulate and cross-check the written responses of the subjects of the study. The data collected through multiple choice items was tabulated and described in percentage based description along with other responses and the scholarly views being presented. Finally, the major suggested multiracial prospects, challenges and opportunities in multiethnic school learning were sorted out and treated separately.

4. Discussions and Analysis of Data

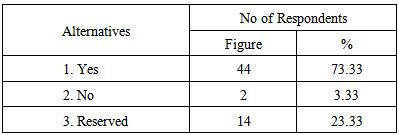

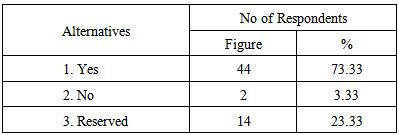

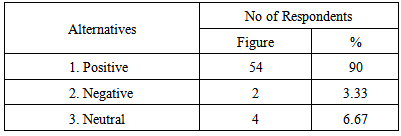

This section tried to discuss and analyze the data of the research. As the data were chiefly gathered through questionnaires of two types of items, (open-ended and multiple choice items), the researcher employed content and thematic analysis to identify the most frequently addressed responses to the open-ended questionnaire, whereas tabular and graphic presentation and discussions were applied to analyze the responses to multiple choice items. l Teachers’ Responses to Open-ended Questionnaire It is frequently reported that the majority of the respondents perceived multicultural education as equity and community-based education. One of the respondents, for example, put the case as: ‘Multicultural teaching approach gives opportunities for learners to learn in harmony with other learners. It initiates coexistence among learners and creates confidence in learners, and that is why it is a must to be implemented in all schools in Ethiopia.’Regarding the responses to ‘how can a school environment provide and handle the learning of students with multicultural backgrounds’, the frequently suggested strategies are by promoting: multipurpose school mini-media services, multicultural art centers, diversity music clubs, school community awareness raising programs, and by encouraging clubs or volunteer groups to present culture-focused news or newsletters, stories, drama or plays at flag ceremony. There also suggested the importance of creating linguistic action zone, where students communicate in their own tongue, and diversity action zone, where students of diverse backgrounds are merged to exercise retelling their own indigenous stories and social life experiences. As can be seen from Table 1, 44 respondents out of 60 were likely to substantiate that incorporating multicultural education in school curriculum is important. Fourteen respondents appear to be reserved, while only two informants seem to react negatively. That is to say, 73.33% of the teacher respondents reported that they supported the inclusion of multicultural education into school curriculum, whereas 33.33% would appear reserved to make their opinions or responses apparent. The latter respondents might have their own rationale for not choosing either ‘Yes’ or ‘No’. It is also clear that only 3.33% responded against incorporating multicultural education in school curriculum. Table 1. Responses to incorporating multicultural issues into school curriculum

|

| |

|

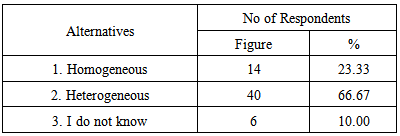

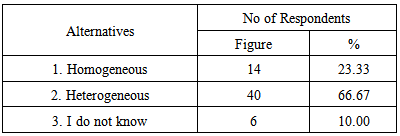

Overall, it could be deduced from the above table that the majority of the respondents reacted positively saying: ‘Yes’. Similarly, the content analysis reveals that the most frequently reported reasons is that it is important to infuse multicultural concepts and perspectives into school curriculum because it would appear that the respondents generally acknowledge Ethiopia as a center of multiethnic and multicultural nations and nationalities. As to the responses to the question: ‘how do you think you best teach students of heterogeneous socio-cultural backgrounds’, some teachers would seem that they mainly use traditional teaching methods-telling, explaining, clarifying... Some other informants reported that they sometimes used questioning and answering methods. This goes in line with Gay’s (1997) argument that the value given to multicultural approaches to school learning is mainly neglected. One convincing reason is that teachers are supposed to acquire multicultural competence just by the very nature of their profession. The assumption is that teachers could develop how to inspire, communicate and understand students from diverse socio-cultural backgrounds in the course of their teaching experiences (Sinagatullin 2003). In this sense, it appears that what matters a lot in teaching students from diverse cultural and ethno-linguistic origins is just the experience of years of teaching.It was noted by the respondents that the potential challenges or difficulties to implement multicultural-oriented teaching were mainly: scarcity of relevant and supportive multicultural-related teaching materials, lack of multicultural competence and limited school opportunity to exercise own ideas. Others would seem that they become very much concerned about the existence of complex ethnic and cultural diversities in Ethiopia. As to the content analysis, there appeared attitudinal problems towards the notions of multiculturalism. It seems that there are still tendencies towards not to recognize cultural diversity and equality. In some cases, it was felt that one of the challenges could, as to some respondents, be that some teachers might have little exposure to their students’ cultural compositions, or they might have been less familiar with diverse cultural values and customs. As a result, they tended to prefer silence on such issues.Regarding the problems teachers have observed related to teaching multiracial students in their classrooms or school, some reported constraints are: the existence of ethnic or cultural stereotypes, prejudices, negative attitudes towards others’ authentic-self and/or identity marks, lack of a consistent teacher encouragement and the influence of language barriers. The content analysis witnesses that there were respondents who expressed that there seemed to exist misconceptions concerning the need to multiculturalize school learning. It was reported that there were cases in which individuals attempted to spread propaganda saying that ‘school should be free of politics, cultural views and religion’. In fear of this, it appeared as if some teachers felt that they would better not talk about culture related issues in a class. Concerning the responses to the question:’ what classroom opportunities do you give your students to express their own beliefs, ideas or thinking?’ It is perhaps surprising that almost all the respondents would appear that they were less likely to specify anything that could be used to help their students to express their own beliefs, ideas or thinking. The result of the interview and content analysis also proved that teachers became more of lesson dependent and give little room for students to exchange their own related opinions ahead of a topic.l Students’ Responses to Open-ended QuestionnaireThe regularly reported responses concerning students’ understanding of multiracial and multicultural education is that some think that it is an education that could create a ‘network’ among students’ cultural values and life experiences. Others reported that it is an education that reflects the real life stories of different societies. There were also respondents who thought that multicultural education is just education for ‘tolerance’. On the other hand, a great number of student respondents suggested that the main challenges or difficulties to express their own beliefs in school learning are mainly fear of: being joked or laughed at, being called as backward, political attachment to culture related issues, and lack of teacher encouragement’. A case in point is that, as responded by a respondent, the main challenges are that: “Some individuals believe that your ethnic group is savage if you tell them that people in your culture have some different cultural attributes which maybe unpleasant for outsiders. I would be reserved in such cases and often I try to hide my true self from others.” Within this context, the more seemingly recurring challenges as stated by a respondent is:”Some of the students believe or think that some cultures are inferior or superior because of these most of us are afraid of talking about our own indigenous cultural practices, norms and beliefs. Even, when we talk about self, we tend to be selective and often try our best to make others feel happy. However, most often, some of us who come from countryside prefer silence when the insiders are talking. You know, because they may despise us verbally or non-verbally. ”Apparently, as noted in the responses of the students, some students who tried to express their true-self in their own accent were likely to be labeled as ‘rural’ student, (which is reportedly given negative connotation), and others who tended to ‘acculturate urban style of self-expression’ appeared to be more favoured and accepted. As to the results of the content analysis, there existed attitudinal challenges to exercise own identity. One of the teacher respondents, for instance, reported: “The students who come from rural area don’t want to be in the same group with those from urban area during classroom or outside classroom learning practices. I think those from the towns often tend to show-off and marginalize the rural ones. Perhaps, in my view, the rural students are expected to model the urban life styles and so they are supposed to be more of listeners rather than speakers. ” The majority of the students reported that the major opportunities that the school provided are: firstly, students are encouraged to celebrate their own cultural values and practices on a special school culture day. Secondly, though the program was believed to have contributed little to talk about, there reported that there was a good progress in using school mini-media to mediate racial and cultural diversity issues to the school community. These cases are seen as good opportunity to mainstream and legalize cultural values in the school compound.l Teachers’ Responses to Close-ended QuestionsTable 2 illustrates that 66.67% of the teacher respondents admitted that they teach students of heterogeneous cultural composition. In other words, forty out of sixty teachers confirmed that their class is composed of multicultural groups of students. The table also shows that 23.33% of the respondents felt that they teach students of homogeneous culture, whereas 10% of the respondents would seem that they knew little about their students’ cultural composition. It means almost 33.33% of the teachers are likely that they did not get enough awareness about how to teach students of multicultural backgrounds. Table 2. Responses to students’ cultural composition?

|

| |

|

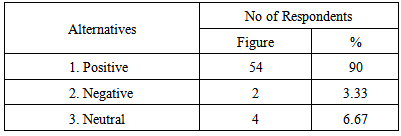

Table 3 displays that while four informants out of sixty would seem that they appear neutral, two respondents rejected the case. Yet, the highest number of the respondents, fifty-four out of sixty appears supportive towards promoting multicultural education in school learning. Table 3. Responses to the attitudes towards promoting multicultural school learning

|

| |

|

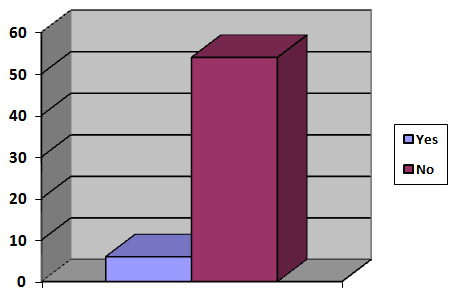

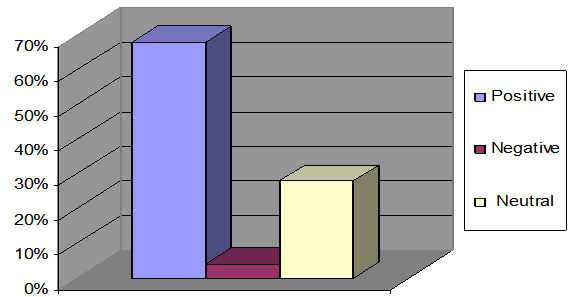

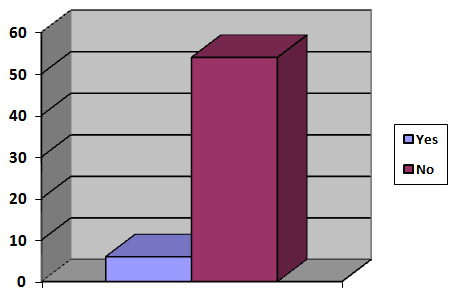

In other words, the result illustrates that 90% of the teacher respondents confirmed the positive influence of including multicultural education in school learning. Whilst 6.67% of the respondents would seem indifferent or uninterested in the idea of promoting multicultural school, 3.33% of the respondents tended to react negatively. By and large, the highest percentage of the teacher respondents shared the idea of implementing multicultural school. As is evidenced from Figure 1, 90%, or fifty-four out of sixty teacher respondents, approved that they did not take course or training on how to teach multicultural students, whilst 10%, that is to say, six teacher informants out of sixty indicated that they took a course or training on how to teach multicultural students. It would seem that the teachers who responded “yes’ might be teachers who are teaching civics and ethical education courses or any related courses, or teachers who might get opportunity to take training on multicultural education.  | Figure 1. Responses to training taken on how to teach multicultural students |

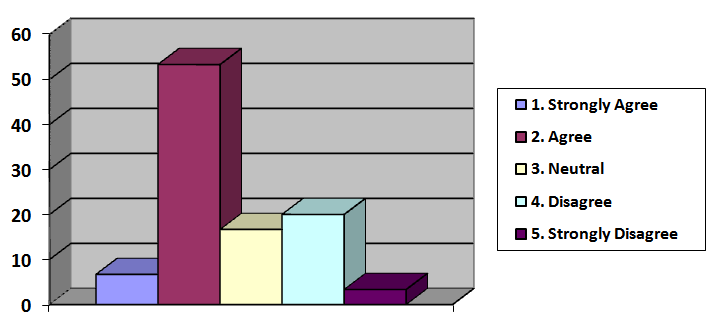

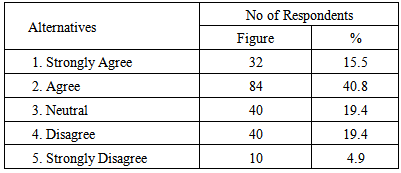

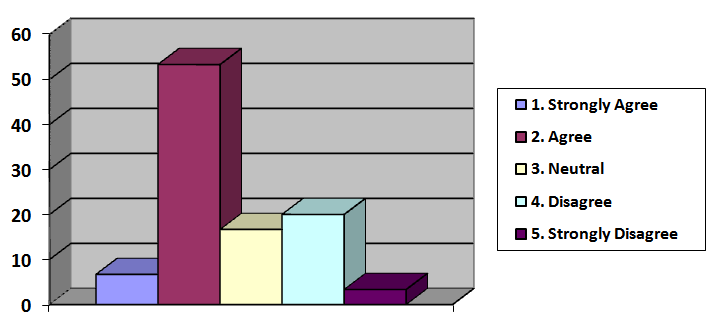

As can be referred from Figure 2, more than 50% of the respondents approved that they agree with the idea that the learning activities in students’ textbooks are applicable to students of multicultural backgrounds. Still, some respondents, around 6%, tended to substantiate that they strongly agree with the applicability of the learning activities to encourage students of diverse cultural backgrounds. However, more than 15% of the respondents shown that they remain neutral concerning this issue. Alternatively, the figure illustrates that of the remaining respondents, 20% would prove that they disagree with the idea that the learning activities in students’ textbooks are applicable to encourage students of multicultural backgrounds. Besides, around 3% tended to indicate that they strongly disagree with the point raised.  | Figure 2. Responses to the learning activities and their applicability |

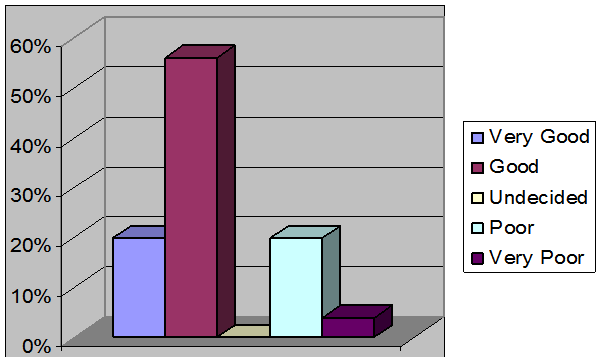

From this, it could be deduced that respondents who responded indicating ‘Disagree’ and ‘Strongly Disagree,’ would suggest the mismatch between the learning activities in the textbooks and their applicability to encourage students of diverse cultural backgrounds. In other words, it sounds that around 23% of the respondents seem to feel uncomfortable with the suitability of the learning activities to motivate students of diverse backgrounds. The remaining, more than 15%, of the respondents appeared ‘Neutral’. In a research, for example, conducted by Ellwein, Grave and Comfort (1990), it has been found out that student interest, participation, and prompting inclusive learning practices characterized successful lessons. Many of the respondents in this research were reported that they acknowledged lessons that generated different student reactions as lessons that challenged students’ thinking. Mostly, lessons were believed to be successful when they were connected to students’ prior experience or actual life realities. Likewise, their result indicated that teaching methods, materials and/or learning activities that were creative, fun and situated within students’ experiences contributed greatly to the success of school learning. Nonetheless, there is no ground to argue that there is always the same approach to establish multicultural school learning. Sinagatullin (2003:3) has, for instance, had the view that: ‘Obviously, no single multicultural formula will work in all schools or situations. “Successful innovations” notes Cusher (1998), “is more likely to occur when educators make the effort to adapt what is known about specific cultural issues and effective schools to their own situation.” So, there is no hard reason to try to apply certain universal principles to multiculturalize school curriculum. It means we should consider actual reality on the ground.  | Figure 3. Responses to whether the school meets the needs of multicultural students |

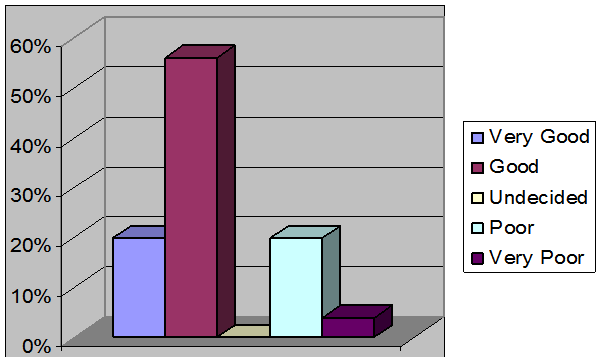

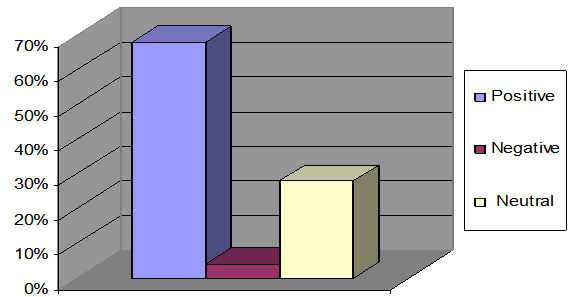

As Figure 3 above shows, more than 50% of the teacher respondents would appear that they think their school is trying to meet the needs of multicultural students. While 20% of the respondents indicated that the school’s attempt to support students of different cultural backgrounds becomes ‘Very Good, the same percent of the respondents showed their disappointment by rating ‘Poor” to their school’s evaluation. Again, less than 5% of the respondents rated ‘Very Poor’ to the school’s attempts to meet diverse students’ needs. Statistically, more than 70% of the respondents tended to approve that their school provides something that helps them to exercise their own opinions or cultural issue in school learning. The result of the content analysis and interview show the respondents might evaluate their school’s attempt to meet the needs of multicultural students positively, perhaps because, the school was reportedly allowing the students to celebrate special culture day in the school compound. Or else, it was hinted that the school was trying to encourage students to address cultural issues through school mini-media. l Students’ Responses to Close-ended Items Figure 4 reveals that more than 65 % of the respondents confirmed they have positive attitude to promoting multicultural education in school learning. Of the respondents, more than 20% would seem that they showed indifference in the issue. In contrast, less than 5% of the respondents likely to reject multiracial and multicultural values in school learning. | Figure 4. Students’ attitude towards promoting multicultural concept in school learning |

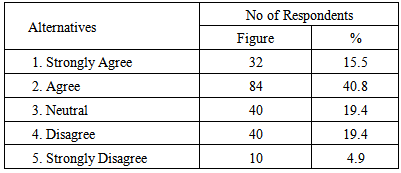

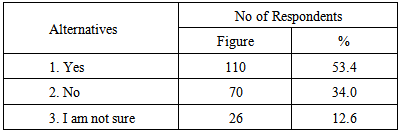

The result of the written responses witnessed that the highest number of teacher respondents reacted to this point very constructively. To be precise, a respondent stated:” School learning should respect our diverse cultures because all students should know the realities of their societies. We have multicultural origins but, so far, we know little as we are not provided an all-inviting school opportunity. In this case, the result could imply that there is a positive and welcoming school community to implement multicultural sensitive school learning practices. As can be seen from Table 4, eighty-four out of 206 respondents-that is, 40.8% would seem to claim that the learning activities in the students’ textbooks are relevant to encourage the participation of students of multicultural backgrounds. The table also indicates that 15.5% of the student respondents approved that they strongly agree with the idea raised. While 19.4% of the respondents identified themselves as neutral, the same percent of students, that is, 19.4% confirmed their disagreement. The remaining 4.9% of the respondents noted that they strongly disagree with the idea. Table 4. Responses to the applicability of learning activities to diverse students

|

| |

|

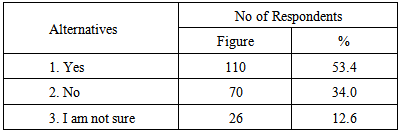

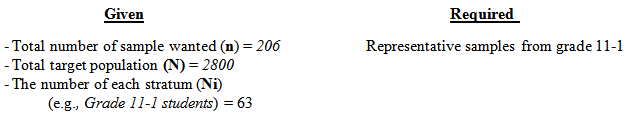

In most cases, it would seem that 24.3 % of the respondents are likely to react against the idea presented. Yet again, the result of the teachers’ response to the same item indicated 23% of the informants suggested that the learning activities are less likely to encourage multicultural students. But more than 15% of respondents appear reserved or neutral. This implies the need to reorganize the learning activities to meet the students’ demands.As can be deduced from the ongoing discussions, there is a need to mainstream diverse socio-cultural and ethno-linguistic issues into formal academic materials. Of all, the crux of the matter is that in a multicultural setting, every classroom mirrors students of multicultural and multilingual backgrounds. So, one can argue that successful learning, in a multicultural setting, requires an intercultural approach where students are responsible for, firstly, respecting the presence of others in all their acts, and, secondly, acquiring the habit of listening to each other and negotiating differences in opinions. This, in one sense, empowers students to experience multiple ways of thinking. In the other sense, students may come to understand that learning is not just about the mastery of the content of a subject matter, but also, it is about the generation of diverse thinking, and mutual reflection, (Kiyukano 2005).Table 5 reveals that the highest percentage of the respondents would seem to approve that they feel secured to express their own opinions and cultural views anywhere in their school. In other words, 53.4%; - that is 110 students out of 206, indicated that they are comfortable to express their ideas and cultural issues in class or outside in the school compound. However, Table 5 also presents that 34.0%, that is, seventy out of 206 students would seem that they felt unsafe to communicate their own opinions and cultural views during schooling. Table 5. Students’ responses to expressing their cultural views during learning

|

| |

|

As shown in Table 5, the remaining 12.6%, or in other words, twenty-six out of 206 student respondents, reported that they were not sure whether they could communicate their opinions freely. The reason behind might be that students may not try-out to express their ideas or they may lack opportunities to link the learning activities to their own cultural contexts.

5. Results

The overall result proves that the frequently addressed challenges to entertain multiracial concepts in school learning mainly revolves around, fear of self expression, fear of being cast out, politicizing the concept of multiculturalism, inadequacy of exposure to multicultural responsive environment, the existence of routine culture of teaching, attitudinal and conceptual challenges. On the other hand, the commonly reported opportunities are the presence of constructive views about multicultural education, the celebration of a special school culture day, the presence of mini-media cultural service, the feelings of open-mindedness, and the valuing of the existence of cultural and ethnic diversity in the country. Major Findings l Politicizing the Issue of MulticulturalismIt was found out that some respondents tended to politicize issues related to multiracial and multicultural aspects. As to the analysis, some respondents noted that the secret behind multiculturalizing school system is to legalize the politics of the governing party in school curriculum. However, Phillips (2007:14) asserted the attempt to incorporate multicultural perspectives in school system is seen as: ‘...the route to a move to a more tolerant and inclusive society because it recognizes that there is a diversity of cultures, and rejects the assimilation of these into the cultural tradition of the dominant group.” Yet, the critical point is whatsoever the reactions in multiculturalizing school learning may be, it challenges teachers and educators to capacitate all students to respect the contributions of cultural resources to academic success. l Lack of Qualified and Multiculturally Competent Teachers The result shows almost all teacher respondents confirmed that they did not take courses or trainings on how to teach students of diverse cultural backgrounds. This suggests that little attention is given to multicultural perspectives in teacher training programs. This appears in consistent with the argument given by Gay (1997) and Miller, Kostgrize and Gearon (2009) that there is great variability in what counts as sufficient preparation to take on the challenges of teaching students of cultural diversity. To be precise, teacher education institutions need to have clearly set standard and inclusive criteria that constitute a minimum of qualifications for teachers teaching in a multiracial and multicultural setting. Research findings, Ríos and Montecinos (1999), show that proficient multicultural teachers who consider their students’ cultural backgrounds and lived experiences are more skillful in how to ‘reduce the potential for discriminatory schooling practices’ against the students. In the words of Ríos and Montecinos (1999: 67): ‘If multicultural educators believe that race/ethnicity matters, then increasing the representation of students of [diverse backgrounds] in the educational programs requires that teacher educators examine the understandings, needs, and perspective that these students bring to their classrooms.’ They further argue that multicultural sensitive teachers are experts in the field because they bring to the school: ‘an understanding of the students' culture, experiences, and academic challenges resulting in greater empathy and affirmation of their students.…’ (Ibid) l Conceptual ChallengesAnother major finding is that some of the respondents directly or indirectly refer to lack of academic exposure to the concepts and essences of multiracial and multicultural approaches to school instructions. This implies that there exist misconceptions or conceptual challenges to implement multicultural-responsive school learning. In this regard, it has been made clear that it is of little significance to try to create a multicultural school without upgrading the school communities’ knowledge of multiracial and multicultural perspectives and without empowering the school communities to activate the very concept of multicultural school learning (Miller, Kostgrize and Gearon 2009; Milem et al. 2005). Nor is it possible to talk about institutionalizing multicultural education while neglecting the level of the understanding of the school community. l Attitudinal ChallengesIt seemed that some respondents likely to feel that creating a multicultural school could be a way to control any cases of interethnic and interreligious conflicts or frictions within the school. As to this group of respondents, the objective to legalize multicultural school learning is not to introduce it as an autonomous academic discipline, but as means of calming school problems stemming from intercultural tensions or ethno-linguistic or interethnic conflicts. However, it appears that such opinions could be emotionally driven, or politically- motivated, or it could emanate from lack of enough awareness or knowledge of the principles and concepts of keeping diversity in education. Yet, even if what was speculated might come true, scholars like Sinagatullin (2003) and Gay (1997) have had the view that multicultural approaches to school learning is not only limited to capacitating teachers with the potential of how to minimize or avoid racial, linguistic, religious, social class and/or gender linked prejudices, but also it provides students with equal school opportunities to communicate their own thoughts and beliefs in the process of learning. As to Santrock (2006) schools can improve students interethnic relations by building up students’ experience of ‘…sharing one’s worries, success, failures, coping strategies, interests and other personal information with people of other ethnicities’ (Ibid. 353). Capacitating students to get the opportunity to voice their own opinions and thinking could help students ‘ ”step into the shoes” of peers who are culturally different and feel what it is like to be treated in fair or unfair ways’ (Ibid). It means empowering students to develop intercultural competence and constructive attitudes towards others help the students to upsurge strong bond of school social cohesions. l The Practice of Preset Culture of Teaching The result of the analysis shows that some teachers came to class with a predetermined lesson and method of delivering it. It sounds that there existed a certain routine methods of teaching despite the students’ diverse cultural compositions. Yet, there has been a widespread tendency to acknowledge that teaching culturally and linguistically diverse students does not mean teaching students as usual. It demands (Gallos & Ramsey, 1997:135):….. an ability to accept multiple perspectives on reality, and a tolerance for exploring the often unexamined parts of human experiences-areas blocked by fear, guilt, embarrassment, and denial. Defenses are easy to evoke as individuals look at themselves in ways that often stand in contrast to their espoused definitions of self. Educators wonder if and what students learn. Students question educational methods and their own capacities for growth Interestingly, Sinagatullin (2003) literally argues that culture ignorant school approaches could mean denying the validity and contribution of students’ multiple background experiences. Of all, the crux of the matter is that: is it possible to begin school learning from vacuum or no where? Can we start an academic lesson from something which is out of the students’ mind (i.e. from abstract)? Is it rational to expect students’ school success just based on contrived and predetermined pedagogical tasks or activities? For this reason, if a school program is meant to empower its learners to experience school success, the students’ multiple cultural profiles should be valued in the schooling process (Willie, Edwards & Alves 2002). In conformity with this, the result of a research conducted by The New London Group (1996), has indicated that curriculum and classroom teaching which is based on the students own life experiences and discourses that are sensitive to socio-cultural and sub-cultural diversities would accelerate students’ school success. Specifically, overtly organized and culturally sensitive instructions would empower students to initiate and handle own learning practices. This could enable students to develop a meta-language that accounts for developing multiple ways of thinking. l Fear of Being MarginalizedAs can be deduced from the discussion, the six major finding of this research is that some of the respondents were less likely to communicate their own true feelings, cultural values and beliefs in fear of that there could be possibilities of being stigmatized or marginalized. As cited in the content analysis, it would seem that some town students may externalize the rural ones during break time. Even worse was that some informants reported they sometimes withdrew themselves from classroom questioning and answering session in fear of others’ murmur or disgusting facial expressions incase the class heard different ideas. Some scholars contend that some students whose cultural values and identities are given less value or ignored in the schooling process may feel they are marginalized or externalized from other groups who are given more concern (Gay 1997; Hollins 2008). Such students may feel frustrated, and may withdraw themselves from the so called mainstream groups of the school. l The Feeling of LiberalismThe seventh major finding is that some respondents of the study described themselves as “open-minded or flexible” in their approach to others. They cited that they respected listening to their partners’ opinions and then, tried to respond positively no matter how strange the other’s idea is. It is, therefore, genuine to say that there is an existing light indicating that some individuals are likely to value the habit of listening to others and ending dialogues or talks peacefully. The idea of open-mindedness could also imply that the respondents are tending to exercise the sense of progressiveness or liberalism in their manners. In a similar way, Milem et al.(2005) and Banks & Banks (2001) suggest that people who are multiculturally open-minded could not only learn from the success stories of others, but also, they become active to adapt the constructive lessons and life stories of others to their own life. They develop manners which are against intrusive behaviors that provoke people to judge others’ realities just from the outsiders’ point of views.

6. Conclusions

In today’s modern society, individuals struggle to gain the right respect and recognition of their identity: language, culture, beliefs and ethnic origins. They strive hard to resist systems that ignore or undermine the demands for recognition of ethno-linguistic and cultural identities. As a result, questions are keeping on increasingly raising concerning how to maintain the healthy co-existence of the differences in social, cultural, linguistic, religious, ethnic identities and values in school learning. The critical question would be how to explore and exploit diversity issues in a responsive and constructive manner in school learning.Convincingly, teaching in multiracial and multicultural setting appears to be more challenging. It often pressurizes us to feel uncertain and anxious about how to approach students of diverse backgrounds, how to behave in the classroom, and how to deliver an all-inviting lesson regardless of students’ differences. So, in today's schooling, where individuals become increasingly assertive, there is a great pressure to acknowledge and entertain students with different perspectives. Illustratively, it is possible to secure diversity by varying the content of our syllabi and teaching methods, being more aware of classroom dynamics, and by paying more attention to our students and to how they are acting in the learning process. Our ability to respond to and be enriched by these challenges could certainly determine not only the success of our students and institutions, but also the success of the nation.This study has tried to explore and identify multiracial prospects and challenges and in multiethnic school learning. As to the result, students face a number of challenges to communicate their own socio-cultural experiences. Some of the common themes stated as challenges are: fear of self expression, lack of enough multicultural awareness, inadequacy of exposure to multicultural responsive environment, fear of being politicized, the existence of complex ethno-linguistic diversity, and conceptual and attitudinal challenges. On the other hand, the main opportunities are the existence of constructive views towards multicultural concepts, the broad role of school mini media service, the celebration of special school culture day, the feeling of open-mindedness and the recognition of the existence of multiple cultural and ethno-linguistic diversities in the country. In a nutshell, the motives behind creating multiracial and multicultural responsive school learning are that students should not only be challenged to study hard and think critically, but they should also be encouraged to think differently. Students should be exposed to diverse life experiences that could capacitate them not only how to coping with success but also with failure. Secondly, schools should be the leading agents where students practise and personalize how to challenge and negotiate the differences arising in the process of interpersonal and interethnic interactions smoothly. Thirdly, students should acquire not only the habit of appreciating rather than criticizing or fearing differences, but also the habit of acting against cultural discriminations, prejudices and stereotypes whenever they confront them in their life instances. Schools should not only provide the conditions in which students learn and experience respecting human variations, dignity and equity, but also should facilitate the experience in which students celebrate their differences in all their walks of life. Putting differently, what make formalizing multicultural school critically important are the demands to answer these questions: What do we need to know to communicate and understand an individual from a different culture? What are the needs for entertaining multiple differences and thinking in school learning? What are the academic significances of knowing others’ culture and cultural attributes? Why do misunderstandings and confusions arise as members of different cultures attempt to communicate? What needs to be done to build up citizens who are proud of who they are, where they belong to, and who are responsive to their country’s diverse ethno-linguistic and socio-cultural values? Should cultural resources be taken as assets or liabilities to modern schooling? How can we secure students’ cultural diversity, co-existence and continuity in their school and after school life?

References

| [1] | Banks, J. A. & Banks, C. A. M. 2001. Multicultural Education: Issues and Perspectives (4th Ed.) New York: John Willey and Sons. Inc. |

| [2] | Cheng, V.J. 2004. Inauthentic: The Anxiety over Culture and Identity. USA: Rutgers UP. |

| [3] | Ellwein, C., Grave and Comfort. 1990. ‘Talking about Instruction: Student Teachers’ Reflections on Success and Failure in the Classroom.’ JT E, Vol. 41, N. 5, (pp. 3-13) |

| [4] | Gallos, J.V & Ramsey, V.J. 1997. Teaching Diversity. Listening to the Soul, Speaking from the Heart. USA: Jossey-Bass Publishers. |

| [5] | Gay, Geneva. 1997. Multicultural Infusion in Teacher Education: Foundations and Application. Lea body Journal of Education. Vol. 72 No. 1(pp 150-177). |

| [6] | Hollins, E. R. 2008. Culture in School Learning (2nd Ed.). New York: Routledge. |

| [7] | Hooper A. 2005. Culture and Sustainable Development in the Pacific. Australia: ANU Press. |

| [8] | Irvine, J. J. 2003. Educating Teachers for Diversity – Seeing With a Cultural Eye. New York |

| [9] | Kiyukanov, I. 2005. The Principle of Intercultural Communication. Boston: Pearson Edu. |

| [10] | Malamah- Thomas, A. 1987. Classroom Interaction. Oxford: Oxford University Press. |

| [11] | Milem, J., et al. 2005. Making Diversity Work on Campus: A Research-Based Perspective. USA: Association of American Colleges and Universities. |

| [12] | Miller, J., Kostgrize, A. and Gearon, M. 2009. Culturally and Linguistically Diverse Classrooms. New Dilemmas for Teachers. Great Britain: MGP Books Group. |

| [13] | Ovando, C. J., Collier, V. P, & Combs, M. C. 2003. Bilingual & ESL Classrooms: Teaching in Multicultural Contexts. (3rd Ed.). USA: McGraw Hill. |

| [14] | Phillips, Annes. 2007. Multiculturalism without Culture. New Jersey: Princeton University. |

| [15] | Ríos, F. and Montecinos, C. 1999. 'Advocating Social Justice and Cultural Affirmation: Ethnically Diverse Pre-service Teachers' Perspectives on Multicultural Education', Equity & Excellence in Education, 32: 3, 66 - 76 |

| [16] | Santrock, John W. 2006. Life-Span Development. (10thEd). USA: McGraw Hill Higher Educ. |

| [17] | Seelye, H. Ned, & Wasilewski, J. H. 1996. Between Cultures: Developing Self-identity in a World of Diversity. USA: NTC Contemporary. |

| [18] | Sinagatullin, I. M. 2003. Constructing Multicultural Education in a Diverse Society. USA: The Scarecrow Press Inc. |

| [19] | Sliwak, Anne. 2010. “Educating Teachers for Diversity: Meeting the challenges.” From Homogeneity to Diversity in German Education. Germany: Heidelberg University Pres. |

| [20] | Taylor, Charles. 1994. Multiculturalism. New Jersey: Princeton University Press. |

| [21] | The Council of Ministers of FDRE. Cultural Policy. Addis Ababa, October 1997. |

| [22] | The New London Group. 1996. ‘A Pedagogy of Multiliteracies: Designing School Futures.’ Harvard Educational Review, Vol. 66. Number 1, (pp. 66-90). |

| [23] | Wiersma, W. 1995. Research Methods in Education. An Introduction. USA: Allyn & Bacon. |

| [24] | Willie, Edwards, R. and Alves, M. J. 2002. Student Diversity, Choice and School Improvement. London: Bergin & Garvey. |

N = Total number of target population- (2800)

N = Total number of target population- (2800)  Ni = the number of each stratum size (e.g. total number of grade 11 students, i.e.1480) Based on the above formula, 109 students were required from the grade 11 sections, whereas 97 students were determined to be taken from the grade 12 sections. Note that it was decided to round-off every digit to the nearest whole number to avoid fraction numbers.The grade 11 student population of the schools was grouped into 22 classes in which each, on average, consisted of 63 students. The grade 12 student population was arranged into 19 classes, in which each, on average, consisted of 69 students. As the target population was grouped into 41 sections, it was decided to apply the formula for stratified random sampling to specify the representative samples of each class. Accordingly, to determine the number of representative samples to be taken from each subgroup (for example, from Grade 11 sections), the same formula was applied.

Ni = the number of each stratum size (e.g. total number of grade 11 students, i.e.1480) Based on the above formula, 109 students were required from the grade 11 sections, whereas 97 students were determined to be taken from the grade 12 sections. Note that it was decided to round-off every digit to the nearest whole number to avoid fraction numbers.The grade 11 student population of the schools was grouped into 22 classes in which each, on average, consisted of 63 students. The grade 12 student population was arranged into 19 classes, in which each, on average, consisted of 69 students. As the target population was grouped into 41 sections, it was decided to apply the formula for stratified random sampling to specify the representative samples of each class. Accordingly, to determine the number of representative samples to be taken from each subgroup (for example, from Grade 11 sections), the same formula was applied.  That means the study involved five students from each of grade 11 classes, which altogether were 110 sample students. Using the same formula, the study involved five students from each of grade 12 classes that were totally 95 students. Finally, to determine the individual student to have been taken from each specified grades and classes of the schools, systematic random sampling was used. To apply this, first the complete name list of each class was collected from classroom teachers. Then, the formula N/n = k, (Ibid), was applied to decide the interval of the individuals to have been selected from each class’s name list, that is: N = Total population of a group\class n = the number of sample to be taken from a given group/classK = a common factor used to determine the interval of individuals in the name list The study has also included 60 teachers, which was 75% of the targeted teacher population teaching at grades 11 and 12 at Menelik II and Dejazimach Wondirad Secondary and Preparatory Schools.

That means the study involved five students from each of grade 11 classes, which altogether were 110 sample students. Using the same formula, the study involved five students from each of grade 12 classes that were totally 95 students. Finally, to determine the individual student to have been taken from each specified grades and classes of the schools, systematic random sampling was used. To apply this, first the complete name list of each class was collected from classroom teachers. Then, the formula N/n = k, (Ibid), was applied to decide the interval of the individuals to have been selected from each class’s name list, that is: N = Total population of a group\class n = the number of sample to be taken from a given group/classK = a common factor used to determine the interval of individuals in the name list The study has also included 60 teachers, which was 75% of the targeted teacher population teaching at grades 11 and 12 at Menelik II and Dejazimach Wondirad Secondary and Preparatory Schools.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML