-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Education

p-ISSN: 2162-9463 e-ISSN: 2162-8467

2015; 5(1): 20-25

doi:10.5923/j.edu.20150501.04

Quality of Research Projects in Medical Education – Does Extended Time Lead to Higher Quality?

Eva Ekvall Hansson, Margareta Troein, Anders Beckman

Lund University, Department of Clinical Sciences in Malmö/Family Medicine

Correspondence to: Eva Ekvall Hansson, Lund University, Department of Clinical Sciences in Malmö/Family Medicine.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2015 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

The research projects produced in higher education are important not only for developing skills in critical appraisal in order to give students tools for working evidence-based but also as a measure of quality of higher education. When the Bologna Process was implemented at Lund University in Sweden, the courses in research projects were extended and are now performed at the basic level as well as the advanced level in the program, in the form of one bachelor thesis in the middle of the program and one master thesis at the end of the program.The aim of this study was to analyze whether the extension of the research project course in the medical program at a Swedish university had affected the quality of the research projects in the course. One teacher read all of the papers from the students on the extended 20-week course and the previous 10-week course. During the reading of the papers, scoring rubrics were used to grade the papers. A comparison between the two courses was made. The comparison showed that, in the items “title,” “abstract,” “introduction,” “ethics” and in the total sum, the projects from the long course were given statistically significantly higher grading than the projects from the short course. More projects from the long course passed the exam than the short course. We conclude that extended timeseemed to improve quality of scientific writing in some of the items, but not all, and also resulted in more projects passing the exam. The item “ethics” is difficult for students to handle.

Keywords: Research projects, Quality, Scoring rubrics

Cite this paper: Eva Ekvall Hansson, Margareta Troein, Anders Beckman, Quality of Research Projects in Medical Education – Does Extended Time Lead to Higher Quality?, Education, Vol. 5 No. 1, 2015, pp. 20-25. doi: 10.5923/j.edu.20150501.04.

1. Introduction

- Health care is constantly developing and great challenges are approaching due to changes in demography, the panorama of disease, the rapid development of knowledge, and changes in health care organization [1]. The necessity of clinicians to be skilled in critical appraisal is obvious [2]. Therefore, medical programs also emphasize critical appraisal in order to give students tools for working evidence-based [1]. The Bologna ProcessIn Europe, the process of formalizing the European Higher Education Area was initiated through the Sorbonne Declaration in 1998 and formalized through the Bologna Declaration in 1999 [3]. Forty-seven countries in Europe agreed, on a voluntary basis, to work toward unifying the European higher education sector [3]. Since then, there have been Ministerial Conferences every two years, where the ministers have expressed their will through the respective Communiqués (the Prague Communiqué in 2001, the Berlin Communiqué in 2003, the Bergen Communiqué in 2005, the London Communiqué in 2007, and the Leuven/ Louvain-la-Neuve Communiqué in 2009, the Vienna/ Budapest Communiqué in 2010 and the Bucharest Communiqué in 2012). The Bologna Process emphasizes student-centered education with the focus on intended learning outcomes [4]. Yet another aim of the Bologna Process in the next decade, stated in the Leuven/ Louvain-la-Neuve Communiqué, was the significance of reporting on the implementation of the Bologna Process [3]. Implementation of the Bologna Process in SwedenThe Ministry of Education and Science in Sweden reported in 2003 on the first progress on implementing the Bologna Process in Sweden [3]. The implementation had begun on several levels, such as the adoption of a system of easily readable and comparable degrees, the adoption of a system essentially based on two main cycles, and the establishment of a system of credits and promotion of mobility. The two main cycles include a bachelor degree in scientific writing on the basic level and a master thesis on the advanced level [3]. In 2012 there were in all 52 higher education institutes in Sweden who contributed to the report on the implementation of the Bologna Process [3]. One major part of the Bologna Process is the European Credit Transfer and Accumulation System (ECTS). With the ECTS, programs and qualifications can be interpreted correctly. One basis for this is the design and validation of learning outcomes, which can be objectivized [5]. Outcome-based teaching and learningIn outcome-based teaching and learning (OBTL), outcomes of learning and teaching are defined specifically to enhance teaching on a particular course or program [4]. One of the features of OBTL is that teaching should be done in a way that increases the likelihood that most students will achieve the outcome of the course [6]. Thus, constructive alignment is also an essential part of OBTL since it is student-centered and outcome-focused, and intended learning outcomes, learning activities and assessment tasks are aligned to each other [4]. Constructive alignment can well be used in the context of teaching practical skills, such as in research project courses in medical education programs.Research project coursesThe Swedish National Agency for Higher Education is the public authority that reviews the quality of higher education institutions in Sweden. The agency regards the research projects produced in higher education as important [7]. According to this, the Swedish Government has conducted a detailed report about the future of medical education in Sweden, where the implementation of a new goal concerning students’ participation in research is suggested [1].Many colleges and universities promise improvements in students’ thinking, and teachers turn to active learning strategies, such as OBTL, to achieve this [8]. Courses in how to write a scientific paper are examples of how to involve students in processes that will lead to more meaningful and enduring learning, perhaps even improvement of thinking [8]. The medical programs in Sweden are academic education and therefore have close ties to research and science [9]. In Sweden, therefore, research project courses are a mandatory part of the medical programs. In these courses, the research process and the student’s capacity for critical thinking are enhanced [10]. Research project courses can comprise OBTL, meaning that the intended learning outcomes of the course are specified, pronounced and aligned with learning activities, such as independently writing a scientific paper [4]. The examination is also aligned with the learning outcomes and often performed in a threefold way: the production of a scientific paper, an oral presentation and defense of the paper, and opposition on another student’s paper. Providing examiners with detailed rubrics can improve the quality of the examined task and the generalizability of the rubrics used [11]. Also, in order not to expose the student to arbitrariness and to stimulate learning, the use of rubrics can be appropriate when defining criteria for passing the exam [12]. Since spring 2012, scoring rubrics have been used in the medical program at Lund University. The scoring rubrics have been tested and showed strong inter-rater reliability and high inter-rater agreement [13]. The rubrics are now available for students, supervisors and examiners through the Lund University website [14]. Before the Bologna Process was implemented in the medical program at Lund University, the students wrote a bachelor thesis at the end of the program but no master thesis. When the Bologna Process was implemented [15], research projects were extended and are now performed at the basic level as well as the advanced level in the program in the form of one bachelor thesis in the middle of the program and one master thesis at the end of the program [16].Lund University has also emphasized research projects as important in the medical program. The extended course probably means that the students have opportunities to do more in-depth literature research when they write their background, pay more attention to the discussion, and dedicate more time to data collecting. The students have the opportunity to devote more attention to the process of performing a research project, even if it is the product that is examined. However, whether the extended course leads to higher quality in the research projects is not proven. The aim of this study was therefore to study whether the extended course has affected the quality of the research projects in medical education at a Swedish university.

2. Methods

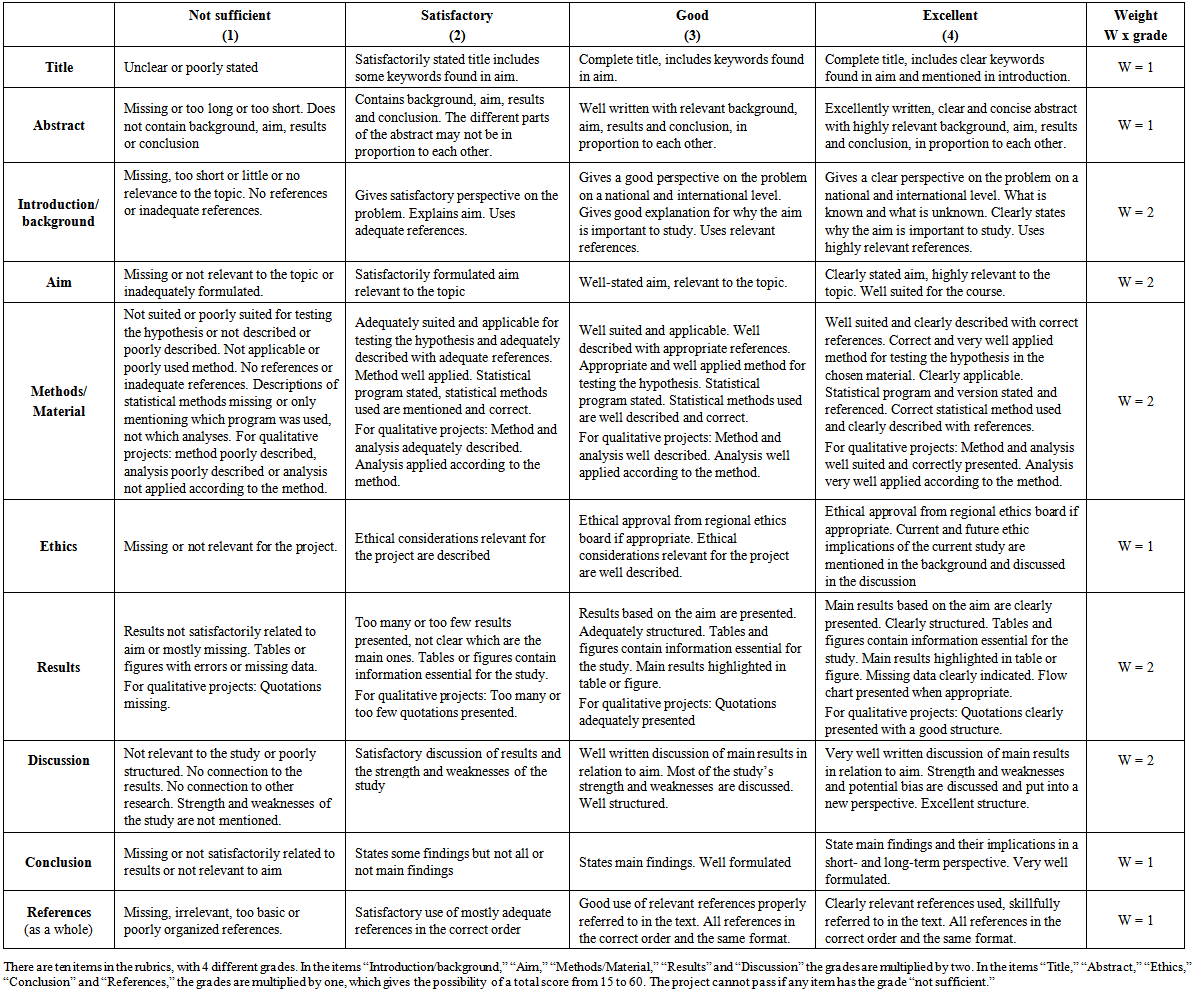

- At the medical school of Lund University, the research project course was formerly placed in the eleventh and last semester, comprising ten weeks (short course). During the spring semester 2012, the course was moved to the tenth semester and expanded to twenty weeks (long course). Thus, at the end of the spring semester in 2012, students from the final short course and students from the first long course were examined. Scoring rubrics for assessing research projects in the program have since then been used in the courses and are available for students, supervisors and examiners, in both the long and the short course [14]. The scoring rubrics were originally based on the European Credit Transfer and Accumulation System Scale (ECTS) and the grading scale has been criterion-referenced and modified into a 1-to-4 scale with 10 different items. The scoring rubrics have shown strong inter-rater reliability and high inter-rater agreement [13]. The scoring rubrics are shown in table 1.

| Table 1. Rubrics used in the study |

3. Results

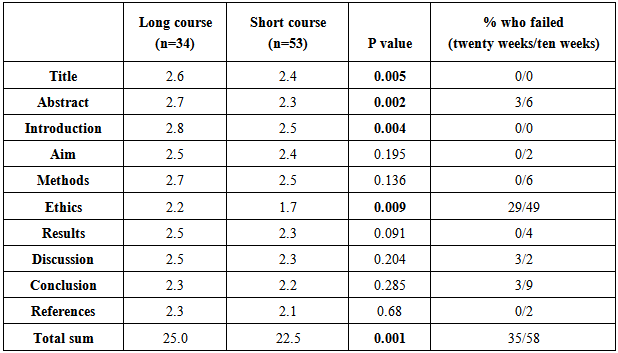

- In the items “title,” “abstract,” “introduction,” “ethics” and in the total sum, the projects from the long course was given higher grading than the projects from the short course (p=0.001–0.046). The result of the grading among the two groups is shown in table 2. In the items “aim,” “methods,” “results,” “discussion,” “conclusion” and “references,” there were no differences between the two groups (p=0.09–0.28). Among the projects from the long course, 35% were given the grade “1” in one or more of the items, while on the short course the figure was 58%. In both groups, “ethics” was the item with most frequent grade “1,” 29% in the group with projects from the long course and 49% in the group with projects from the short course (p=0.009).

|

4. Discussion

- The extension of the research project course at the medical school at Lund University seems to have resulted in improved skills in writing title, abstract, introduction and in ethical considerations, as well as the overall sum of the grading of projects. Skills in writing the aim, methods, results, discussion and references did not seem to be improved by the extension of the course. Hence, it seems that the students focus on writing methods, results and discussion when the time is limited. Since it is difficult to give high grading on the item “reference” if the grader is not an expert in the actual research field, the absence of difference between the groups on this item is probably caused by the assessor not being an expert in all the different research fields. Also, the personal characteristics of the student may be important for learning complex scientific concepts [18].The same assessor read and graded all the projects. The projects were anonymous and the assessor had no knowledge of what course the project was done in. The same scoring rubrics were used for both courses, disregarding the difference in time. Therefore, we expected differences between the two groups. Also, after the Bologna Process has been implemented, the research project course in the fifth semester (bachelor exam), includes a theoretical part with seminars and lectures as well as a written project. We therefore expected differences between the two groups in the item “method,” which was not the case. We also expected that more time would give the students opportunity to pay more attention to the discussion, but there were no differences between the groups on this item. Almost 50% of the students had “not sufficient” on the item “ethics” in the short course. Even if the figures had improved to 29% on the long course, it is still an item that probably needs more attention from the teachers on the course. We used only one assessor to grade the projects. The assessor is experienced in reading and reviewing research projects from students in the program. Also, the scoring rubrics have shown strong inter-rater reliability and high inter-rater agreement [13], and we therefore believe that one assessor was enough and that our findings are sound.It is possible that the item “references” would be graded differently if each project were graded by an expert in the actual research field, which is the case when the students are examined in the course.The number of articles published in scientific journals is increasing and all health care personnel are doing their best to use best evidence when making decisions about the care of individual patients [2]. Both producers of research and users of research are essential for the application of research and theories in practice [19]. Not all physicians become researchers, but the effort to emphasize research projects in the medical student programs in Sweden and at Lund University will hopefully help physicians to apply evidence-based medicine in their practice.The results of the study can be used to further develop the rubrics, the website of the program, and probably also the research project course.

5. Conclusions

- Since health care is constantly developing and great challenges are approaching, the necessity of clinicians to be skilled in critical appraisal is obvious. Therefore, medical programs emphasize critical appraisal in order to give students tools for working evidence-based. The Swedish National Agency for Higher Education regards the research projects produced in higher education as important. Because of this, and the implementation of the Bologna process, the medical program at Lund University has extended the course in research projects to be performed at the basic level as well as the advanced level in the program in the form of one bachelor thesis in the middle of the program and one master thesis at the end of the program (formerly only a bachelor thesis). However, whether this extended course leads to higher quality in the research projects was unclear. Therefore, using scoring rubrics, we compared the quality of the research projects in the former short course, and in the extended course. This comparison showed that the quality of research projects had improved in the extended course in the items “title,” “abstract,” “introduction,” “ethics” and in the total sum. The extension of the course also resulted in more projects passing the exam (65% versus 42%). The item “ethics” seemed to be difficult for students to handle in both courses.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML