-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Education

p-ISSN: 2162-9463 e-ISSN: 2162-8467

2015; 5(1): 1-8

doi:10.5923/j.edu.20150501.01

Evaluative Research of the Mentoring Process of the PGDT (With Particular Reference to Cluster Centers under Jimma University Facilitation)

Worku Fentie Tegegne

Teacher Education and Curriculum Studies Department, Jimma University, Ethiopia

Correspondence to: Worku Fentie Tegegne, Teacher Education and Curriculum Studies Department, Jimma University, Ethiopia.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2015 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

The objective of the study was to evaluate the mentoring process of the PGDT program which was under the supervision of Jimma University in the regional states of Oromia and SNNP, Ethiopia. The method of the research used is evaluative and the instruments used to collect data are questionnaire and interview through which mentors’ knowledge of the program, competence, commitment to their roles and their professional attributes, the nature of the mentoring practice, the working climate of the mentees and others were looked at. And it is found out that the mentoring process hasn’t been consistent to the plan the fact that stake-holders had no a clear understanding of the program; the mentees were overloaded; appropriate mentors weren’t assigned by schools (assigning mentors disregarding their field of study, merit and experience and what they were teaching at times); mentees were assigned at primary schools (the level which they were not supposed to work at nor prepared and trained for); the roles of mentors misunderstood by mentees, mentors, and education officials; lack of commitment from mentors, supervisors and education officials of different levels; supervisors and mentors failure to give the inputs they are supposed to due to their limited knowledge of the programme, etc. To reverse the situation: all parties who, one way or the other, involve in the program me need to have a clear understanding of the program and reach at a consensus about how the program should be run, acquainting the roles and responsibilities and the accountability associated with to every stakeholder and providing the necessary and available documents, including program objectives and strategies, to all stakeholders beforehand.

Keywords: PGDT, Mentoring, Supervision

Cite this paper: Worku Fentie Tegegne, Evaluative Research of the Mentoring Process of the PGDT (With Particular Reference to Cluster Centers under Jimma University Facilitation), Education, Vol. 5 No. 1, 2015, pp. 1-8. doi: 10.5923/j.edu.20150501.01.

Article Outline

- PGDT: Post graduate diploma for teaching, a program which trains teachers for secondary schools in Ethiopia. Mentoring: The process of guiding pre-service teachers by respective experienced secondary school teachers / mentors as part of the PGDT.Supervision: The component of the PGDT which is specifically designed to see whether the mentoring practice is well underway by the supervisors/ the University lecturers.

1. Introduction

- The education system in Ethiopia has been in problem for years. According to the Education and Training Policy of Ethiopia [7] and Kedir [6], the system has suffered problems of relevance, quality, accessibility and equity. The objectives are not ones that take the society's needs in to account nor do adequately indicate future direction. Besides, the contents and mode of presentation of the curricula are not in such a way that they develop students' knowledge, cognitive abilities and behavioral change by level, to adequately enrich problem-solving ability and attitude, Federal Democratic Republic Government of Ethiopia [2] in [6].The Teacher Education programme in the system is expected to shoulder missions that are far-reaching in scope through the promotion of social, economic, and political changes in schools. The preparation of teachers who can promote students’ learning in schools should be a priority agendum of its programmes, MoE, [8]. However, this programme hasn’t been immune from the aforementioned problems. It has experienced long standing problems. It has failed to produce teachers with the expected knowledge, skills and attitude. According to the Draft Curriculum Framework for Secondary School Teacher Education Programme in Ethiopia [8], till recently, it hasn’t had strong policy. Even after having the needed policy, according to the Document, the programme has been in trouble .The same document further explains that the teacher education in the country still staggers to produce teachers who are competent in subject areas and can effectively promote the learning of students in schools. This might be ascribed to structure of the programme. The experiences of other countries show that failing to put the appropriate structures in place has a bearing on the outcome and effectiveness of a programme. The document by MoE [8] confirms this. The pedagogical content knowledge of teachers has been taken lightly. Researches on teacher education show that teachers’ professional knowledge base must address how they teach a specific content in their subject areas MoE [8]. So, voluminous contents on learning theories, teaching methodologies, and assessment would be of little help unless candidates are assisted to see how these issues can be made meaningful in the subject they teach (ibid).Noting this, the teacher education programs have undergone structural changes as the result of the 1994 Education and Training Policy. For instance, pre-service secondary level teacher education has been reduced from four years to three. Other aspects of changes have apparently been made to conform to the change in the duration of time. As a result, example, the National Framework for Teacher Education System Overhaul that outlines the rationales for reforms, missions, vision, and the objectives of teacher education in Ethiopia was issued in 2002. It also outlines a set of reform tasks needed to improve the teacher education system. There has been much endeavor of making lessons student-centered, truly-engaging, and real-life-like since then. Example, a professional development course called Higher Diploma has been running to effect student-centered and 'active learning' methodologies. Besides, as indicated before, the preparation of modules along student-centered approaches has been in practice. Apparently, all these efforts are to prepare student teachers to be effective teachers. And these teachers have been made to experience schooling reality through the programme practicum. Besides, nowadays, a new post graduate programme has been put in place where the pre-service teachers are taking professional courses and experiencing actual schooling experiences.In the past, the training and recruitment of teachers, in general and secondary school teachers in particular, had no the emphasis it requires. Those who had first degree in the fields required would be chosen and assigned without due consideration of his/her academic profile, interest toward the profession and professional ethics s/he possesses. Coupled with others, these problems have had tremendous repercussions on the quality of education in a broader sense. To address these and other problems, a task force that was duly engaged in activities for developing a sound teacher education programme and the needs of the country had been identified through analysis of national policy documents and strategies, MoE [8]. Furthermore, teacher educators had been allowed to reflect on the TESO programme and suggest possible direction for improvement. And empirical evidences of teacher education programmes and theoretical bases of teacher education had been examined: experiences of various countries taken through different means. So, the conclusions reached at, as a result, were the misalignment of the programme mission and practice, the prevalence of structural problems in the system and the incompetence of teachers’ pedagogical content knowledge.Taking into account all the problems and the shared experiences, what the MoE came up with was introducing the new pre-service teachers training programme, in which student teachers take professional courses coupled with the actual experience of schooling. To this end, mentoring was made as one of the most important components. However, as it is quite a new experience and a multi-faceted one, the researcher pondered how it is executed.In order to achieve the objective, the following basic questions were to be answered.• Is the mentoring practice consistent to the plan?• What are the limitations experienced?• What are the problems faced?• Are the supervisors and the mentors giving the necessary inputs in the process?

2. Ethical Consideration

- After identifying the research problem and developing the proposal, communicating the objective of the research to the organization where I work and others who involved in the process, I asked for letter of recommendation. After securing the recommendation letter that explains the researcher is a staff member of the organization and asks all those concerned to collaborate when and where necessary thanking them in advance for their collaboration. The researcher identified the individuals who involved in the research. And, then, set a schedule of instrument administration. Following, contacting the category of respondents in person and explaining what he wanted to do, he asked them if they were willing to involve in the process. Being granted of confidentiality of the information they give, the respondents would foresee the significance of the research outcome has. With the respondents’ consent, data were collected.

3. Methods and Materials

- The research method used is evaluative as it is used to evaluate the process of the programme. The necessary data collected from the mentees assigned at the schools in the cluster centers under the supervision of Jimma University, Institute of Education and Professional Development Studies (now College of Education and Behavioral Science) and their respective mentors and the staff assigned supervisors. The regional states where the mentees, under the facilitation of Jimma University, were assigned are Oromia, SNNP and Gambela. However, due to constraints of resources, only Oromia and SNNP were considered. Of the six cluster centers in the states mentioned only three were taken. The cluster centers chosen in these states are Jimma and Woliso in Oromia and Bonga in SNNP respectively. These cluster centers were chosen taking into account different factors. As Woliso and Jimma are the nearest centers to Jimma where the researcher reside in, they were chosen to minimize the cost for data collection and traveling, while the researcher’s acquaintance to the mentees, mentors and the zone education officials in SNNP made Bonga to be considered This was helpful in accessing and obtaining the necessary data required. All schools in all centers where there were mentees are included. All subjects’ mentees included because the number was manageable. This is thought to be important that the mentors, the mentees as well as supervisors are of different background that might be important to the research. As to the supervisors; they were all included in the study.

3.1. Sampling Procedure and Techniques

- Mentees The number of the mentees in Jimma, Woliso and Bonga was 4,8 and 60 respectively. All of them were included in the study.Mentors The number of mentors was equal to that of the mentees, as expected. Therefore, the number of the sample mentors was 72.Supervisors The number of the staff that involve in supervision may vary time to time due to different reasons. Nonetheless, all those involved in the supervisory process in the mean time were 18, so regardless of the center they were assigned; all were included in the research.The technique employed to choose representative samples is non – probability.Schools:The list of the schools in each center was received from the concerned education office and those with mentees identified and included.Selection of the mentees: All the mentees assigned in the three cluster centers were included.Mentors and supervisors selection: The mentors of all the mentees were considered. And all the supervisors who involved in the programme were also respondents.

3.2. Instruments of Data Collection

- The necessary data from respondents were collected through questionnaire (from mentees and mentors), and semi-structured interview (supervisors). With all the categories of respondents, questionnaire and interview were the instruments to assess the mentoring process in general through which respondents’ understanding of mentoring, their experiences in the mean time and the limitation and strength in the process they observed looked at. Besides, supervisors were interviewed on their understanding of mentoring and the consistency of the actual practice with the intention. This was done in such a way that some items were prepared and from them some other elicited as the interviewing process was ongoing.

3.3. Method of Data Presentation and Analysis

- The data collected from the respondents were organized involving editing, classifying, coding and ingoing in computer in a way that they show relationship, give meaning and readying for computation of different statistical values. Finally, the processed data were analyzed through the application of SPSS Version 20.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Results

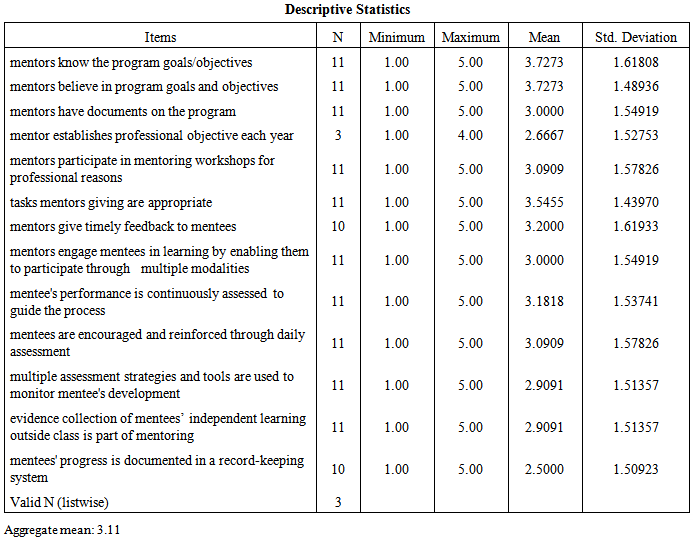

- To achieve the research objective, the collected and processed data were presented in tables on the basis of the variables looked at to assessing the whole mentoring process.The mentoring process

|

|

|

|

4.2. Discussion

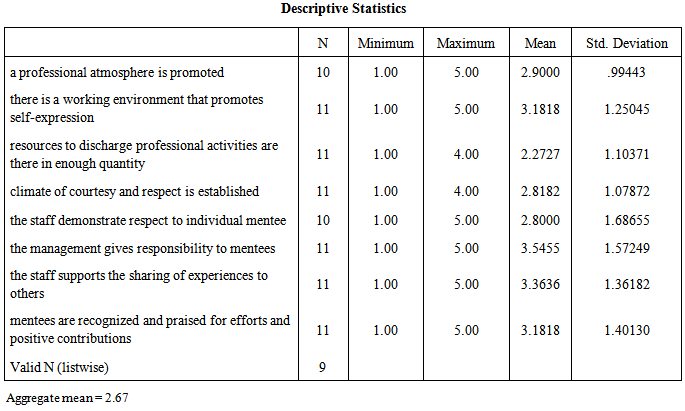

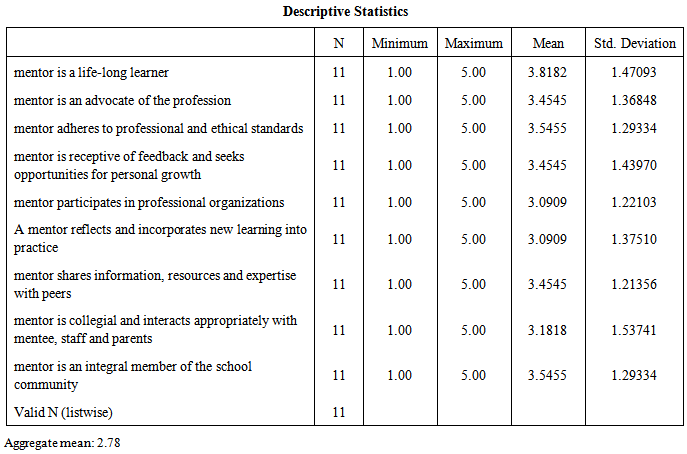

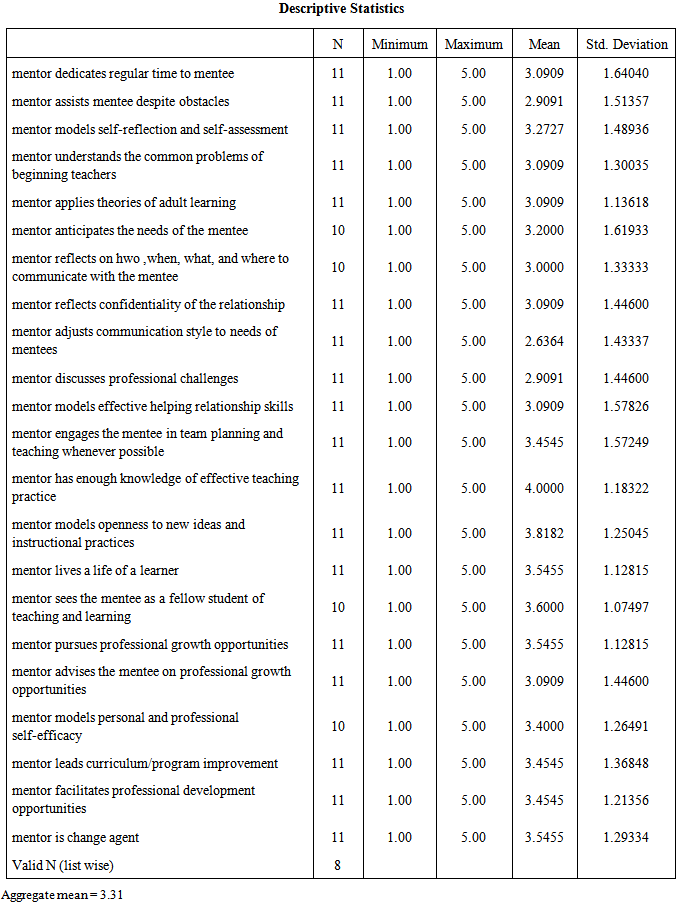

- The objective of the study was to evaluate the mentoring process of the PGDT program which wass under the supervision of Jimma University in the regional states of Oromia and SNNP. The data were collected through questionnaire from the mentees and mentors and interview from supervisors. As the objective of the PGDT program is to produce well- equipped secondary school teachers, to this end, mentors’ role is huge. Their knowledge of the program, competence, commitment to their roles, professional attributes, education level and experience and the working climate of the mentees as well are crucial.

4.2.1. Mentors’ Knowledge of the Program

- The research showed mentors’ knowledge of the program is limited. When mentors’ knowledge of the program considered separately in the process of mentoring, more than anything else, it is very important. Whatever the mentor is capable in what he does, whatever committed he is, whatever conducive working environment the mentee has, it is difficult to imagine the mentor contributes much for the thorough practice of the mentee if he doesn’t know what the program is about. Acquainting mentors of the program by woreda and zonal education officials and supervisors, who have stake in the program implementation, is both a necessity and an obligation. They should know its objectives and their responsibility as stake-holders. From this point of view, since the inception of the program, the Institute (now College of Education and Behavioral Sciences), has given trainings every year. Unfortunately, from experience, those sent to participate in the trainings are either who have no stake in the program implementation process or might be individuals who are not committed to the program (individuals who come to collect per diem). A challenge, which the College was aware of, but unable to rectify.Besides, the research clearly indicated mentees’ relationship with their mentors and the professional support they get shows the mentors’ knowledge of the program is limited. Education officials at different levels seem to have no or little acquaintance to the program. This is not only because of this research ,at the different times and situations like during supervisory field trips, the researcher has had the opportunities to discuss with these individuals on different matters in connection to PGDT (post graduate diploma in teaching) in general and mentoring practices in particular. During those trips, what the researcher understands is that the individuals who lead the teachers’ development programs with the woreda and zone education offices might know about the word PGDT. Beyond this, what the program is all about, why it is designed, its goals, and the important stake-holders who have stake in the program, and their offices roles in implementing the program, etc is beyond their knowledge. When it comes to officials of the offices and other personnel, the situation is far more serious. In such environment, expecting mentors to be better acquainted and execute their activities could be illogical.

4.2.2. Mentoring Practice

- The mentoring practice is believed to be above satisfactory according to mentees and mentors. But it is not wholly corroborated by the data collected and the actual field trips experience of the researcher. As the mentees are would be secondary school teacher, the mentors assigned to support them professionally need to have first degree, apart from the vast experiences and professional and ethical standards expected of them. When we see the professional profile of the mentors, it doesn’t meet the minimum requirement. There are mentors with the education level of diploma. There are some mentors with certificate. Of course, mentors with diploma and certificate might have something to share. They might have teaching experience in abundance that they have accumulated through time. But having this doesn’t qualify them to be mentors. Mentees may resist to be supported by these mentors. What we witness during field trips is this. The mentors may not like to support the mentees either. The other point is mentors’ experience. Mentors selected, relatively, need to be more experienced and in a better professional level than their peers etc. However, as observed from the mentors’ bio data, discussions made between mentees and researcher and researcher and supervisors at different times, there are teachers assigned mentors in their first and second year of teaching. In other situations, where there are more experienced, qualified to the standard, distinguished and teachers with the merit, they are not assigned mentors for different reasons.Subject of qualification is another area which comes into play in mentoring. A mentee who graduated in and teaches physics needs to be mentored by a physics graduate mentor who teaches physics. However, from the research, to some degree, what has been observed is different. An English teacher mentors Amharic teacher (mentee), a history teacher mentors a math graduate mentee teaching math. A mentor who graduated in and teaching history may find it very difficult to give professional support to a mentee who graduated in and teaching mathematics. The professional support he provides might be minimal in math teaching. It is not his fields of specialization. Mentors are expected to share experiences in the area of planning, classroom management, managing contents, selection and application of teaching methods, resources, etc. In the process, to give support, the straight forward thing to be fulfilled is that both mentees and mentors should be qualified in same subjects. A mentor couldn’t support a mentee in a subject he didn’t qualify or not teaching either. His contribution to the mentee might be minimal. Assigning mentors regardless of their qualification and the subject they are teaching might be insensible. Of course, in situations where the kind of mentors required is scarce or where mentors of same subject qualification, same educational level and same subject teaching are not available, this could be tolerated. In a situation like this, it is difficult for the mentee to get the necessary professional support from the mentor. Such practice doesn’t contribute to the achievement of the program goals. In relation to mentoring practice, the other issue is assigning mentors to mentees at different schools where they are not teaching. If things go well as plan, the courage and commitment on the part of the mentors is appreciable. But their contribution to mentees traveling to other schools for hours for one or two days on weekly basis is questionable. However, still, it could be the solution to the problem instead of leaving the mentees without mentors. As far as the program, the mentoring practice in particular, is one of the bottlenecks.

4.2.3. Working Climate of Mentees

- This refers to the professional atmosphere at schools, availability of resources to discharge responsibilities, climate of courtesy and respect in the schools, staff willingness to share experiences with the mentees and whether they show respect towards the mentees, etc. In this regard, though the research shows that the working environment is conducive, some of the real experiences of mentors are far from ideal. A case in point is load. Though the mentees load is not determined in a clear cut manner, as apprentices, their load needs to be reasonable so that they will have time to communicate with their mentors for experience sharing, professional support and do their course works (action research, school and community and practicum) to fulfill the requirements of the training program they are in. But many mentees’ load is far from being fair. There are mentees with weekly load of twenty–seven and above hours. In such condition, it is difficult to think of mentees having a good time as an apprentice and as a student who has course work obligations. There have been times mentees haven’t been sent to tutorials and trainings given by the University. Either they are not allowed to go by education officials at woreda level thinking that is a destruction of the teaching learning process, or intentionally do not inform them to go for their own different reasons. As a result, not only they miss trainings, they fail to do projects and come to their universities at the end of the apprenticeship.

5. Conclusions

- The objective of the study was to assess whether the mentoring process of the PGDT programme was consistent to plan and to pinpoint the impending factors that negatively affect the process.Accordingly, based on the findings, the following conclusions are made.ü In relation to the mentoring process:• The mentoring process hasn’t been consistent to plan. This is because of the following factors: stake-holders had no a clear understanding of the program, the mentees were overloaded, there were mentors assigned who are not appropriate for the role (assigning mentors disregarding their field of study, what they were teaching then, merit and experience, etc.). Besides, there were problems like assigning mentees at primary schools (the level which they were not supposed to work at nor prepared and trained for), misunderstanding of the roles of mentors by mentees, mentors, and educational officials and lack of commitment from mentors and education officials at different levels.ü In relation to the limitations experienced: the following were the problems faced.• Not knowing / having a clear understanding of the program by stake-holders• Overloading of the mentees.• Not assigning appropriate mentors by schools: assigning mentors disregarding his field of study, what s/he teaching at present, merit and experience, etc.• Assigning mentees at primary schools/the level which they are not supposed to work at nor prepared and trained for.• Misunderstanding of the roles of mentors by mentees, mentors, and educational officials.• Lack of commitment from mentors and education officials at woreda and zone levels.In relation to whether supervisors and mentors are giving the necessary inputs:• They were not giving the inputs they are supposed to because their knowledge of the program is not complete.ü In relation to the inputs supervisors and mentors were giving in the process,• Supervisors and mentors weren’t giving the necessary inputs. On the part of the supervisors, it was a problem of commitment and to certain degree; there were misunderstandings of the programme. On the side of the mentors, the problem was misunderstanding of their roles and not knowing what the programme is about.

6. Recommendations

- On the basis of the conclusions made, to curb the situations, the following recommendations are forwarded.a. All parties who, one way or the other, involve in the program need to have a clear understanding of the program and reach at a consensus about how the program should be run.b. The necessary and available documents, including program objectives and strategies, need to be provided to all stakeholders beforehand.c. The roles and responsibilities of each and every stakeholder need to be made clear and hold those who fail accountable.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- First of all, I would like to thank Jimma University for the grant offered. Second and last, my gratitude goes to individuals, including my workmates, who contributed in the research in different ways.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML